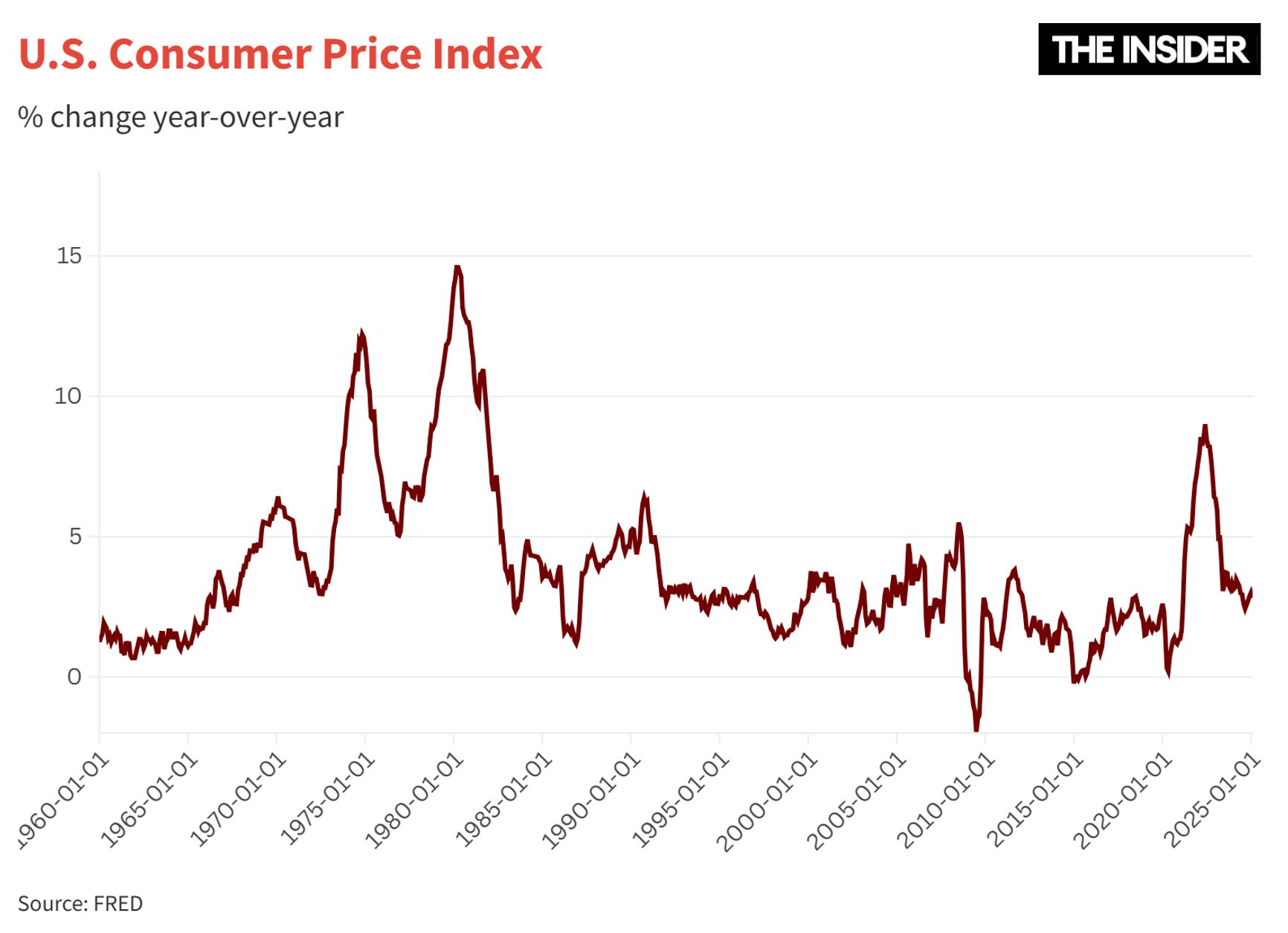

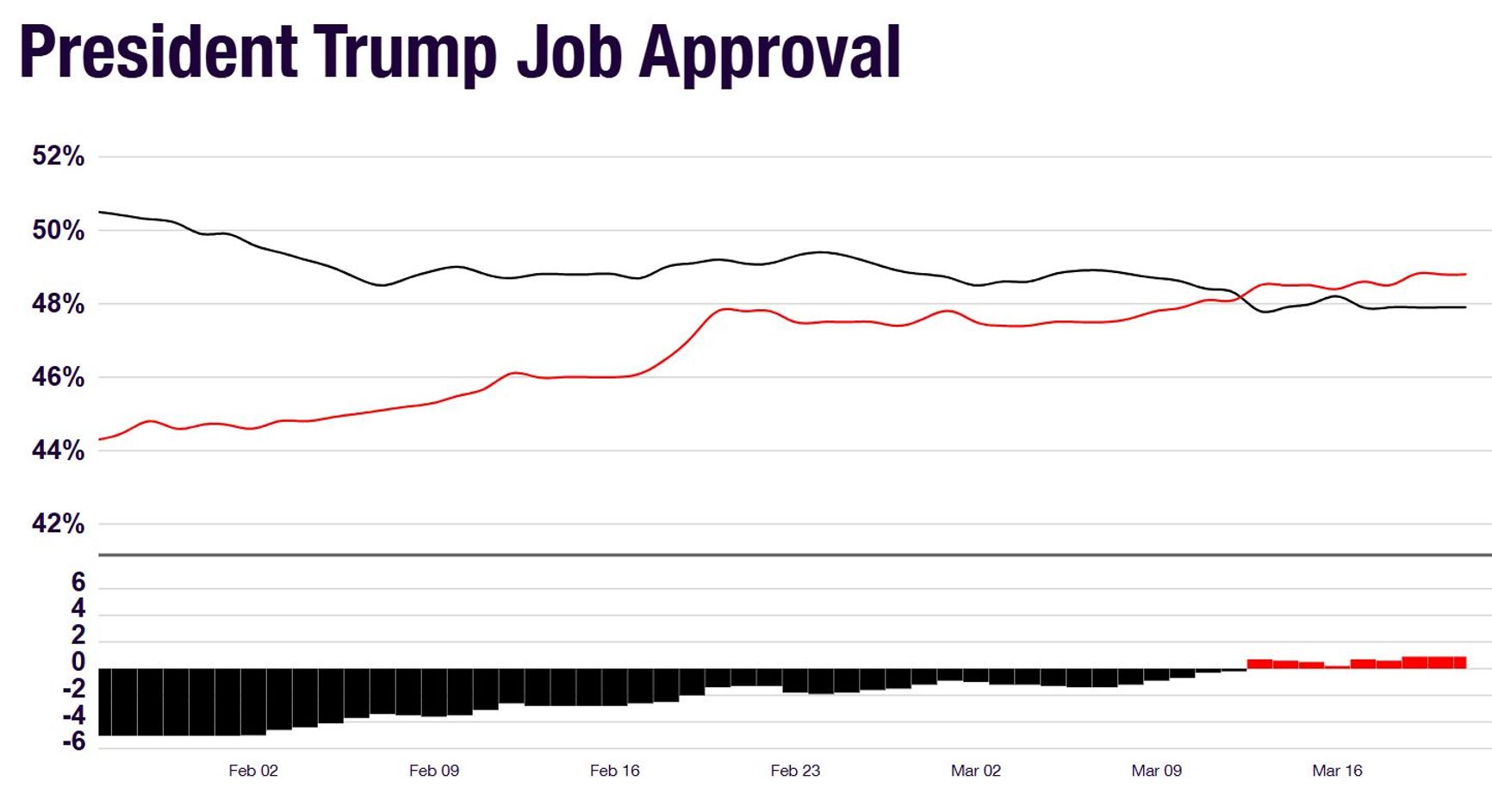

The rise in prices across the United States was one of the main economic forces that propelled Donald Trump back to the presidency. After decades without serious inflation, many Americans were swayed by his pledge to bring down the cost of living — especially the price of food. So far, Trump has failed to deliver: the Consumer Price Index (CPI) remains high, and one of the most politically sensitive issues — the cost of eggs — has become so pressing that the U.S. has begun asking Europe for help with supplies. According to Oleg Itskhoki, a professor of economics at Harvard University, the main drivers of inflation are the aftershocks of the COVID-19 pandemic and the surge in energy prices triggered by the war in Ukraine. Although U.S. monetary authorities have responded by the book, they have not escaped the political fallout. Initially, Trump used inflation fears to pump up his campaign. But now, with his promises unfulfilled, his approval ratings have started to deflate.

How inflation helped Trump win

Prices in the U.S. continue to climb, and the rising cost of eggs is particularly alarming to the public. In January, egg prices surged 15.2% year-on-year — the highest rate in a decade — while overall inflation stood at 3%. The spike was largely due to an outbreak of avian flu, which led to the culling of millions of hens. While macroeconomists tend to dismiss such one-off shocks (especially in agriculture) as irrelevant to broader inflation trends, consumers notice what hits their wallets — and eggs are a daily staple. Politically, this kind of shock contributed significantly to Trump’s election victory.

Trump’s win had two core components — economic and cultural — both of which played an equally important role. On the economic front, inflation was the dominant theme: the highest in 40 years, unseen by two generations of Americans. Inflation had long been dormant across the developed world — since the mid-1980s or 1990s, depending on the country. In 2024, public blame for inflation fell squarely on the Democrats and President Joe Biden, under whose watch prices peaked. Trump, promising to rein in inflation, appeared to be the stronger choice, even though responsibility was shared nearly equally between his first administration and Biden’s.

By 2024, public blame for inflation fell squarely on the Democrats and President Joe Biden, under whose watch prices peaked.

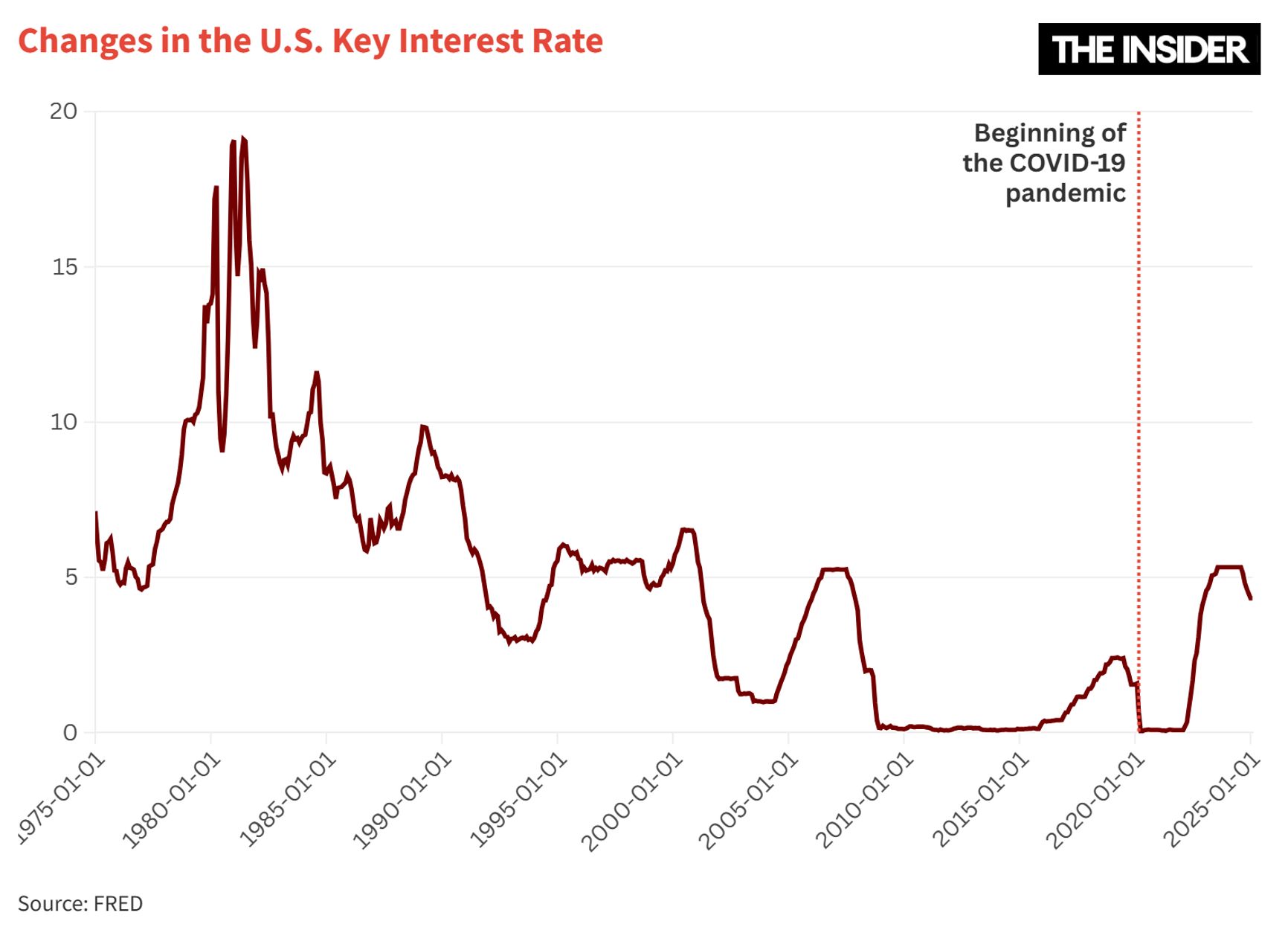

The inflation crisis in the U.S. was largely the result of fiscal stimulus during the pandemic. Two major relief packages were passed under Trump (in March and December 2020), and a third followed under Biden (March 2021). Together, these packages were not inherently flawed — their inflationary effects could have been offset by tighter monetary policy from Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell, who was appointed by Trump in 2018. While inflation is the Fed’s domain, it was slow to act: interest rates weren’t raised until March 2022, likely a quarter or two too late.

Still, the overall outcome was economically successful: fiscal support helped the U.S. recover rapidly from the pandemic. Inflation followed, but it also helped reduce the real value of public debt, which had ballooned due to the stimulus. From an economic perspective, this was a textbook response to a crisis — a large stimulus to sustain demand, followed by inflation to reduce debt (an “inflation tax”), and a soft landing to contain inflation without sacrificing growth. Economists would consider it a near-perfect scenario — more luck than plan.

Voters, however, are highly sensitive to inflation, and the political blame for the situation fell largely on Biden. That’s how the system works: had a different Republican candidate — say Nikki Haley, Marco Rubio, or Ron DeSantis — run in Trump’s place, they too would have made inflation a central campaign issue, and Biden’s camp would likely have lost just the same. In the end, presidents are often blamed for economic trends they don’t fully control. But if a different Republican had come through the primaries, they may well have avoided the culture-war rhetoric that Trump amplified.

The “Three Ps” that fueled inflation

Three major drivers — or “Three Ps” — triggered U.S. inflation: Pandemic, Putin, and Powell. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. government issued direct payments to support Americans — including both unemployment benefits and aid for those still working.

Trump signed two stimulus packages totaling nearly $6 trillion, and Biden added a third worth $2 trillion. Altogether, the $8 trillion in aid amounted to nearly a third of U.S. GDP in a single year (though disbursement stretched across multiple years). The resulting surge in government debt — an increase of 30–40% of GDP — was later eroded by inflation. In effect, the U.S. distributed money broadly, then recouped it through rising prices. Since the stimulus was targeted and the inflationary impact was widespread, the result was a redistribution in favor of lower-income households.

The downside of inflation was that workers lost purchasing power while firms gained. Although wages eventually rose, there was a period during peak inflation when they lagged behind prices. People felt poorer, even if they had received government aid. Those who didn’t change jobs or secure promotions were hit hardest, as their stagnant incomes were quickly outpaced by rising prices. And once again, egg prices became a symbol of inflation’s sting.

The second “P” stands for Putin — referring to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the global spike in oil prices that followed in 2022. Though the spike was temporary, it came at the worst possible time, amplifying inflationary pressure — particularly in Europe. In the U.S., gas prices remained stable, but oil prices rose enough to have an inflationary effect, if only a limited one.

The overall outcome was economically successful — but inflation provoked a strong reaction from the public.

The third “P” is Jerome Powell, the Federal Reserve chair. His delayed response — waiting until early 2022 to raise interest rates — allowed inflation to become entrenched. Experts argue that the Fed should have acted sooner, perhaps as early as August or September 2021.

Together, these three factors — fiscal stimulus from the pandemic, a war-fueled energy shock, and delayed monetary tightening — created the perfect storm for inflation. The Fed’s lag may have lasted 3–6 months, and many central banks around the world followed the Fed’s lead. This raised questions about how coordinated global monetary policy truly is.

No end in sight?

For a time, it seemed developed economies had beaten inflation, much like medicine had defeated old diseases. But a major resurgence proved otherwise. The recent episode gave economists an opportunity to test their models — and this time, inflation came down quickly, unlike in the 1970s. Still, uncertainty remains: inflation could fall to 0–2%, where it ideally should be; it could hover around the current 3%; or a second wave may follow, as it did in the 1980s.

Several factors could trigger renewed inflation, but notably, Trump’s trade tariffs are not likely to have a major inflationary effect, as current tariff levels aren’t high enough to significantly influence price growth. And the Fed can easily offset their impact by keeping interest rates elevated.

A much greater risk would come from Trump, in a bid for political gain, introducing new stimulus measures such as tax cuts or direct cash payments — even in the absence of economic need. Such policies would be inflationary, though it's possible that Republican senators might block them.

Source: RealClearPolitics

Another wild card is Trump’s stance on the Federal Reserve’s independence. Jerome Powell’s term runs through January 2028. He is unlikely to resign early or change course, and while Trump has said he won’t seek Powell’s removal, he frequently criticizes the Fed chair and demands lower interest rates. If Trump were to interfere with the Fed’s independence, that would introduce a high level of uncertainty into U.S. monetary policy.

Given all these uncertainties, a new wave of inflation remains possible — and this time, its political effects would take their toll on a Republican administration.