Donald Trump recently claimed that the temporary suspension of U.S. military aid to Kyiv and the halt in intelligence sharing that followed the Feb. 28 scandal in the Oval Office had no impact on the Ukrainian military. The restrictions lasted only a week before being unexpectedly lifted. Trump appears to be using military assistance as a means of leverage against Volodymyr Zelensky, acting as if Kyiv cannot afford to alienate Washington in its ongoing fight against Russian aggression. In reality, however, U.S. military aid plays a crucial role only in certain categories of weaponry, and overall, the U.S. is far from being Ukraine’s top military supplier. In fact, over three years of full-scale war, the U.S. has sent Kyiv fewer tanks than Poland, fewer air defense systems than Germany, and fewer fighter jets than North Macedonia or Slovakia.

Content

How much aid has the U.S. provided to Ukraine?

How crucial is U.S. support for the AFU?

What will happen to the frontline without U.S. aid?

How much aid has the U.S. provided to Ukraine?

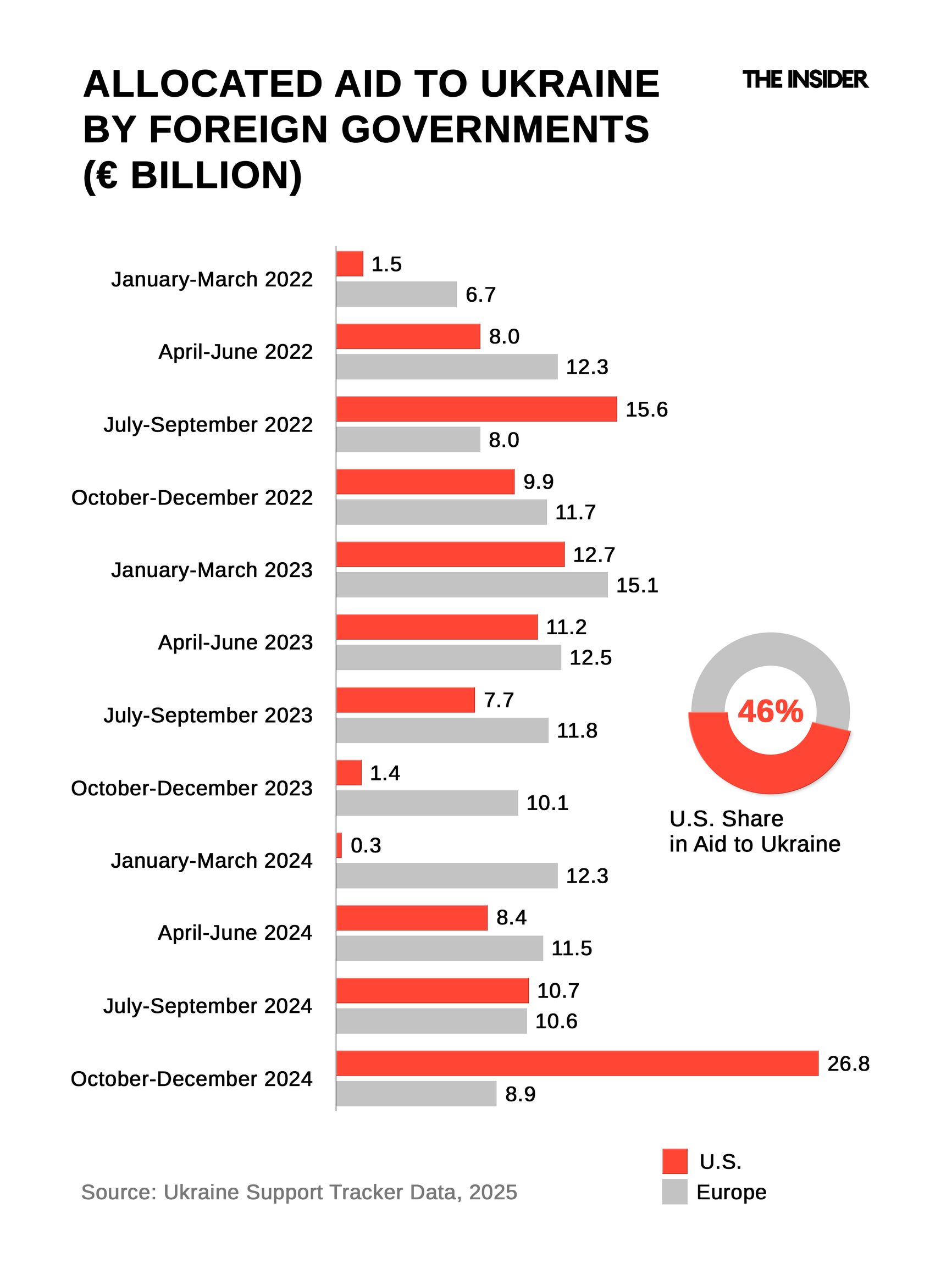

According to the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW Kiel), the most authoritative source on foreign aid to Ukraine over the course of the war, the total allocated U.S. assistance from January 24, 2022 to December 31, 2024 amounted to €114 billion. Europe has contributed even more — €132 billion. When focusing solely on military aid (excluding humanitarian and financial support), the U.S. slightly beats out Europe, providing €64 billion versus Europe’s €62 billion. These figures do not align with Trump’s claims, which range between $300 billion and $500 billion in American support alone.

Allocated U.S. assistance to Kyiv from 2022 to 2024 amounted to €114 billion. Europe has allocated even more — €132 billion.

U.S. aid to Ukraine has been approved through five separate acts of Congress. Funding and coordination fall under Operation Atlantic Resolve (OAR), the umbrella term for U.S. assistance to Ukraine. Since 2022, Congress has allocated $182 billion across 14 different agencies, with the Pentagon receiving the largest share — $123.9 billion. However, of the $182 billion allocated, only $83 billion has been disbursed — i.e., far from all of the aid that Congress approved has actually been made available to Ukraine. When accounting for obligated funds (those committed but not yet paid), the total reaches $140.5 billion, as several dozen billion in approved funds remain in reserve. However, given Trump’s push for budget cuts, they are unlikely to be used — much as $2.7 billion of unused funds were forfeited under the Biden administration due to the fact that they were not allocated in time.

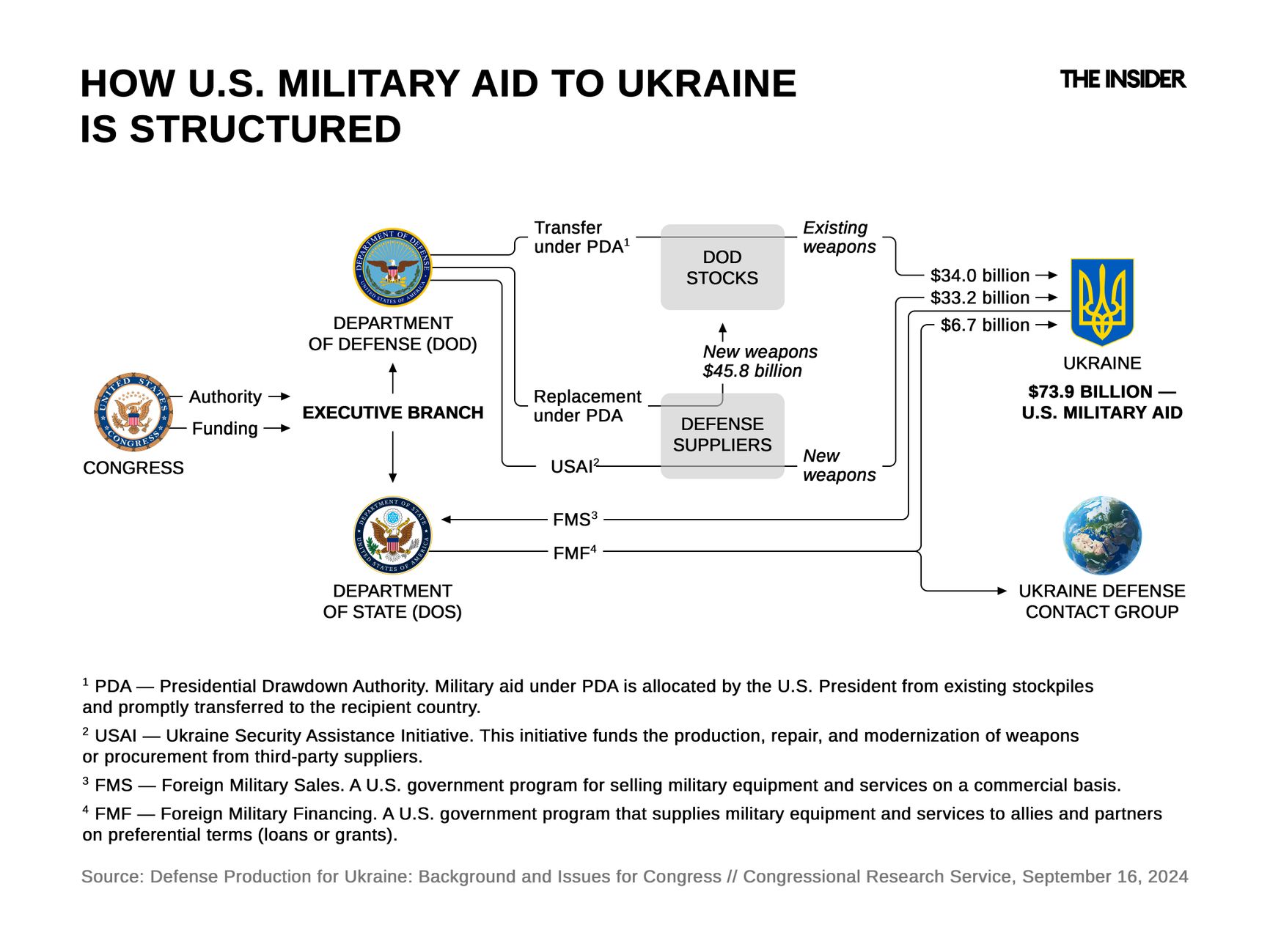

U.S. security assistance to Ukraine follows a three-pronged system in which Congress allocates funds to the executive branch, and the President, Pentagon, and State Department distribute them via three primary mechanisms: the Presidential Drawdown Authority (PDA), the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative (USAI), and Foreign Military Financing (FMF).

The largest share of aid comes through PDA, which allows for the direct transfer of weapons, vehicles, and ammunition from U.S. stockpiles. The total announced PDA packages amount to $34 billion, while an additional $45.8 billion has been allocated to replace transferred equipment. Much of what Ukraine receives via PDA is older equipment, which the U.S. sends to Kyiv before replenishing its own stockpiles with newer, more expensive kit. This system not only aids Ukraine but also modernizes the U.S. arsenal. According to U.S. officials, 90% of PDA-announced supplies have already been delivered. Full implementation of the deliveries — mainly for armored vehicles — was projected to be completed by August 2025.

The second-largest expense under OAR does not directly support Ukraine's military operations. Instead, $44.8 billion has been allocated to the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI) and U.S. European Command for troop deployments, logistics, and maintaining military infrastructure in Eastern Europe.

Ranked third in terms of total U.S. aid to Ukraine are new weapons and ammunition supplies under contracts signed with defense industry manufacturers through the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative (USAI). The total value of announced USAI packages stands at $33.2 billion. However, deliveries under USAI take significantly longer than those made through the Presidential Drawdown Authority (PDA). Based on current projections, the execution of USAI contracts — at a monthly delivery rate ranging from $700 million to $1.1 billion — is expected to continue until 2028.

$6.7 billion has also been allocated through the Foreign Military Financing (FMF) program. The majority of these funds have been used to replenish the stockpiles of other allied countries after they supplied military equipment and armaments to Kyiv. A portion has also covered Ukraine’s urgent military needs, but as of late 2024, only $1.8 billion of the total FMF allocation had actually been spent.

In addition, certain military goods and related services are procured by the Ukrainian government on commercial terms through the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) program. Contracts under this mechanism notably include maintenance services for F-16 fighter jets, the supply of spare parts for previously delivered U.S. weapon systems, and the production and delivery of three HIMARS multiple launch rocket systems (MLRS), financed by Germany.

In total, the allocated and contracted U.S. funds for Ukraine do not exceed $140.5 billion. Meanwhile, the announced deliveries of military equipment and ammunition are estimated at $72 billion, whereas the actual weapons, military hardware, and munitions received by Ukraine amount to just over $50 billion worth.

The actual weapons, vehicles, and ammunition received by Ukraine from the U.S. amount to just over $50 billion.

Is that a lot or a little? For comparison, between 2001 and 2021, the war in Afghanistan cost the United States $2.1 trillion, while from 2003 to 2023 the wars in Iraq and Syria cost even more — $2.9 trillion. Most of these expenses went towards U.S. military operations and long-term veteran benefits, but even when looking only at direct military aid provided to the Afghan and Iraqi armies, the figures are still revealing.

From 2001 to 2020, Afghanistan’s security forces received over $80 billion in U.S. aid. Between 2003 and 2016, the U.S. supplied Afghanistan with 76,000 military vehicles, including 22,000 Humvees and about 1,000 MRAPs, as well as 110 helicopters (Mi-17 and MD-530) and 98 aircraft, including transport, reconnaissance, and light attack planes. This aid did not include small arms, communications systems, ammunition, and other military equipment. Much of the weaponry eventually fell into the hands of the Taliban after Afghanistan’s military collapsed and the U.S.-backed government in Kabul ceased to exist.

The U.S. provided Iraq with over $34 billion in security assistance from 2003 to 2023. More than $20 billion was spent between 2003 and 2013 through the Iraq Security Forces Fund. Unlike Ukraine, Iraq received modern fighter jets, including over 20 F-16s, along with nearly 150 M1A1 Abrams tanks, a handful of Bell 407GX light helicopters, and other military equipment — although much of it was paid for with Iraqi government funds thanks to U.S. credit support.

To date, the U.S. has spent less on Ukraine’s military ($50 billion) than it did on Afghanistan’s security forces ($80 billion) and only marginally more than on Iraq ($34 billion) — albeit on a significantly shorter timeframe. However, in both Afghanistan and Iraq, the local militaries were primarily fighting insurgent forces, and military operations were directly supported by U.S. troops and Western allies, including the participation of small contingents from Ukraine. Afghanistan ultimately fell to the Taliban, while Iraq ended up with a pro-Iranian government and numerous Iranian-backed paramilitary groups. The Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU), by contrast, have managed to resist one of the world’s most powerful regular armies while relying entirely on their own manpower and organizational resources — supplemented with external material and technical support.

To date, the U.S. has spent less on Ukraine’s military than on Afghanistan’s security forces.

When comparing U.S. spending to military aid from Europe, European officials reported that in 2024 alone, the EU, the UK, and Norway provided Ukraine with $25 billion in military assistance, surpassing U.S. contributions for the same period. By the end of 2024, the total military aid delivered from Europe was estimated at €45 billion — which is roughly equivalent to support from the U.S., valued at $50 billion.

How crucial is U.S. support for the AFU?

During their infamous Feb. 28 exchange in the Oval Office, Trump told Zelensky that, “The problem is, I’ve empowered you (turning toward Zelenskyy) to be a tough guy, and I don’t think you’d be a tough guy without the United States. And your people are very brave. But you’re either going to make a deal or we’re out. And if we’re out, you’ll fight it out. I don’t think it’s going to be pretty, but you’ll fight it out. But you don’t have the cards.”

It’s difficult to agree with Trump’s claims that he personally enabled Ukraine’s resistance against Russian forces — particularly given that, since taking office in January, he has yet to approve any new military aid packages and immediately froze the shipment of previously approved arms and intelligence-sharing in the wake of the scandal. However, just a week later, Trump unexpectedly lifted the ban following a meeting between Ukrainian and U.S. delegations in Saudi Arabia, where both sides tentatively agreed on a 30-day ceasefire.

It’s also difficult to take seriously the claim that Ukraine is a “tough guy” only because it has been pumped full of U.S. weaponry — Biden’s administration, after all, had been highly restrained in its military-technical cooperation with Ukraine.

For example, the U.S. has not delivered a single fighter jet to Ukraine — unlike Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway, and Belgium, which are supplying F-16s, or North Macedonia and Slovakia, which transferred four Su-25 attack aircraft and over 10 MiG-29 fighter jets, respectively. The U.S. has also not provided any modern helicopters, instead sending just 20 Russian-made Mi-17V5 helicopters that were originally purchased for Afghanistan but were relocated to neighboring countries after the fall of the U.S.-backed Afghan government.

The U.S. has not delivered a single fighter jet to Ukraine, unlike Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway, Belgium, North Macedonia, or Slovakia.

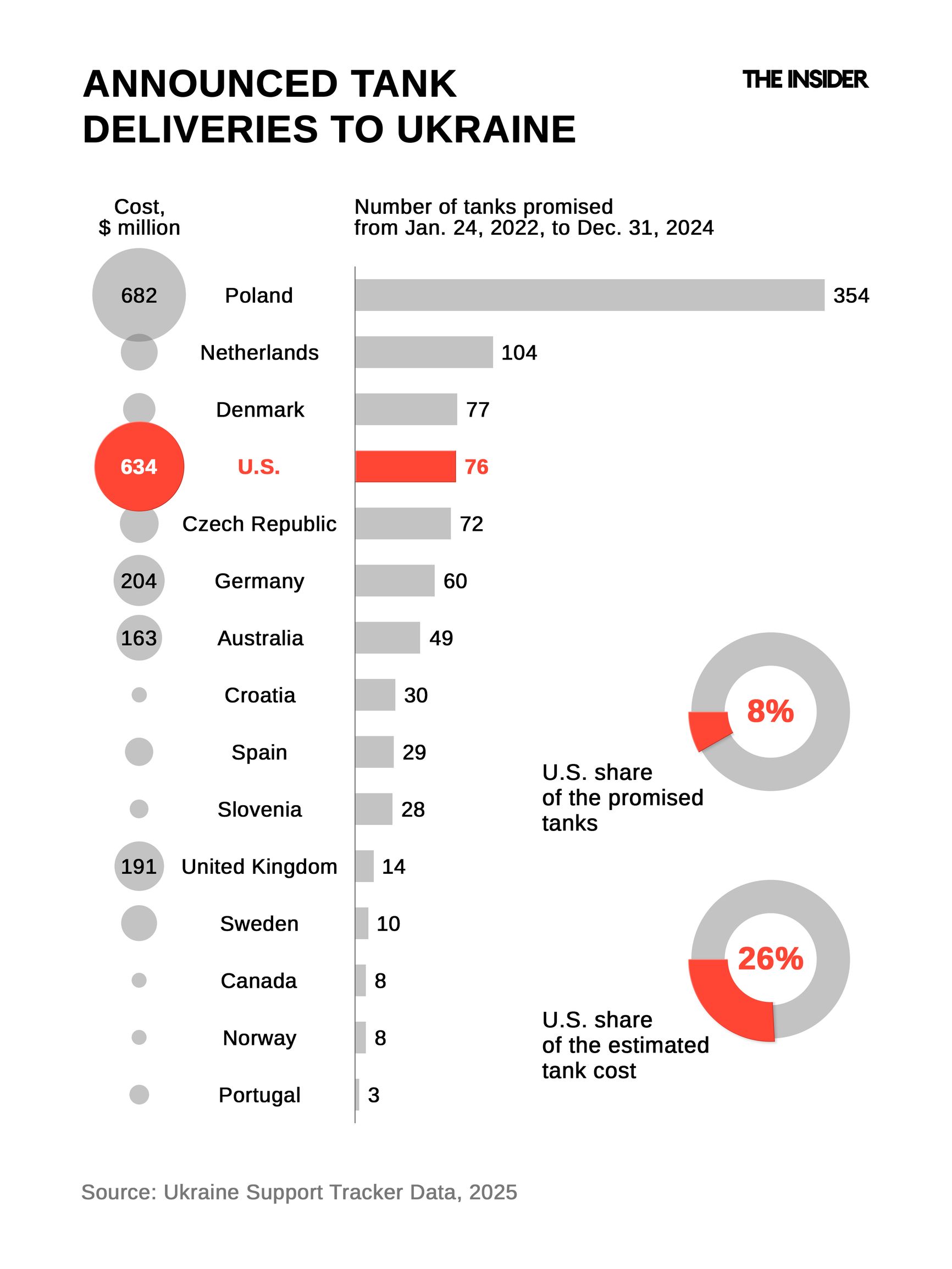

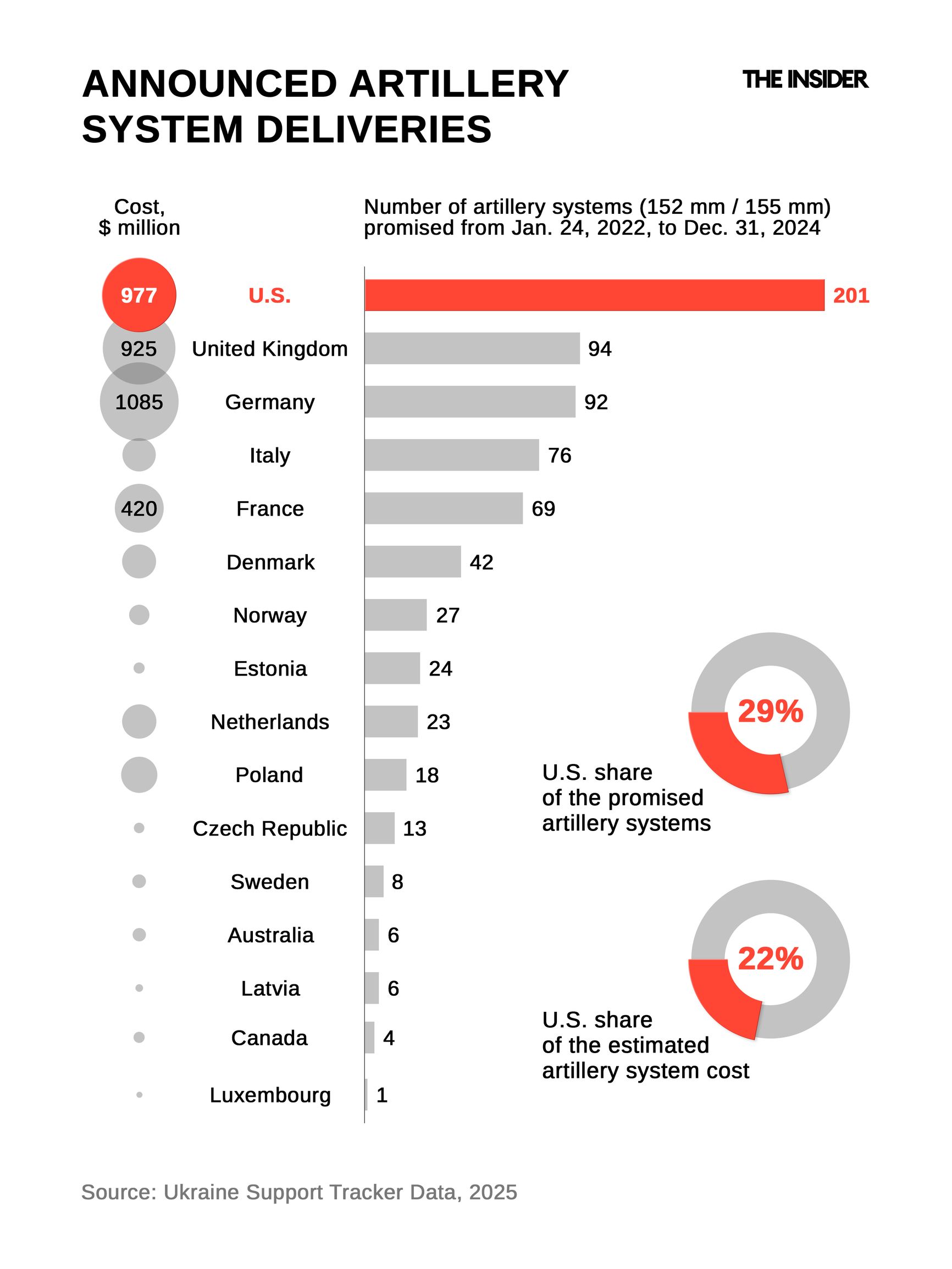

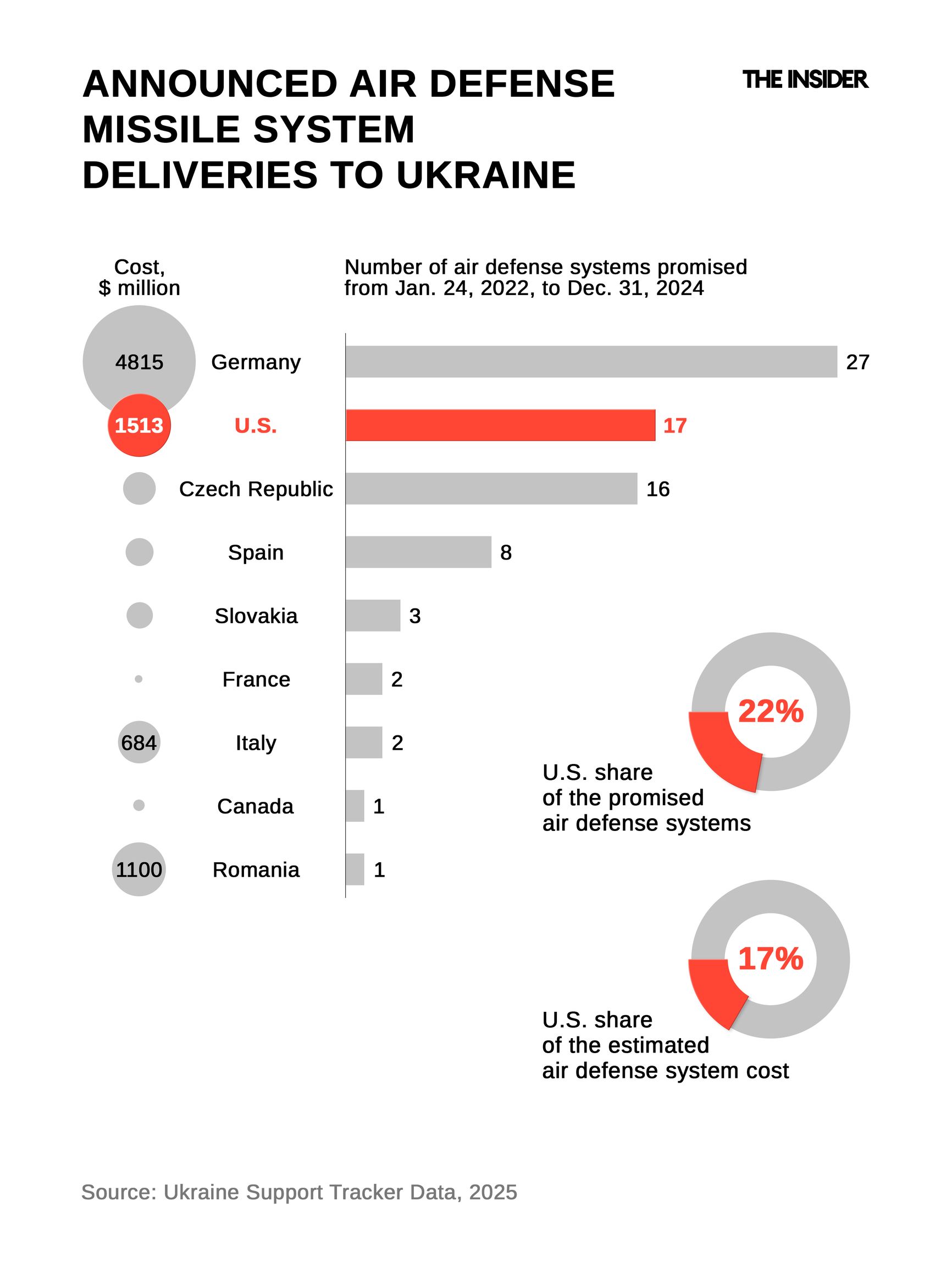

According to a tally by IfW Kiel, when looking at Western allies’ supply of armored vehicles, artillery, and air defense systems as of Dec. 31, 2024, the U.S. plays a relatively modest role.

The U.S. has supplied 76 out of the 922 tanks sent to Ukraine, valued at $634 million out of $2.4 billion. Of these, only 31 are American M1A1SA Abrams, while 45 are refurbished Soviet-era T-72EA tanks. No further tank deliveries are expected from the U.S. Australia and Croatia, however, have announced plans to send 49 M1A1 AIM Abrams tanks and 30 M-84A4 tanks, respectively.

In the infantry fighting vehicle (IFV) category, the U.S. has provided 352 out of 1,294 total IFVs, worth $669 million out of $2.1 billion. These are mostly M2A2 ODS Bradley vehicles, which have proven highly effective in combat. While the U.S. leads in quantity and total cost, two-thirds of all IFVs supplied to Ukraine come from other allies.

As for artillery systems of the 152mm and 155mm calibers, the U.S. leads in number (201 out of 704) but ranks second in financial value after Germany ($977 million out of $4.5 billion). However, 142 of the U.S.-supplied howitzers are M777 towed artillery, rather than the more highly sought-after self-propelled artillery systems on wheels or tracks. The Ukrainian defense publication Militarnyi argues that towed artillery has key advantages such as easier concealment, easier placement in dug-out fortified positions, and reduced vulnerability in case of ammunition detonation, as munitions are stored separately from the gun itself. Meanwhile, upcoming deliveries of Swedish Archer self-propelled artillery (18 units) and Danish and French Caesar howitzers (60 units) will further reduce the relative U.S. contribution in this category.

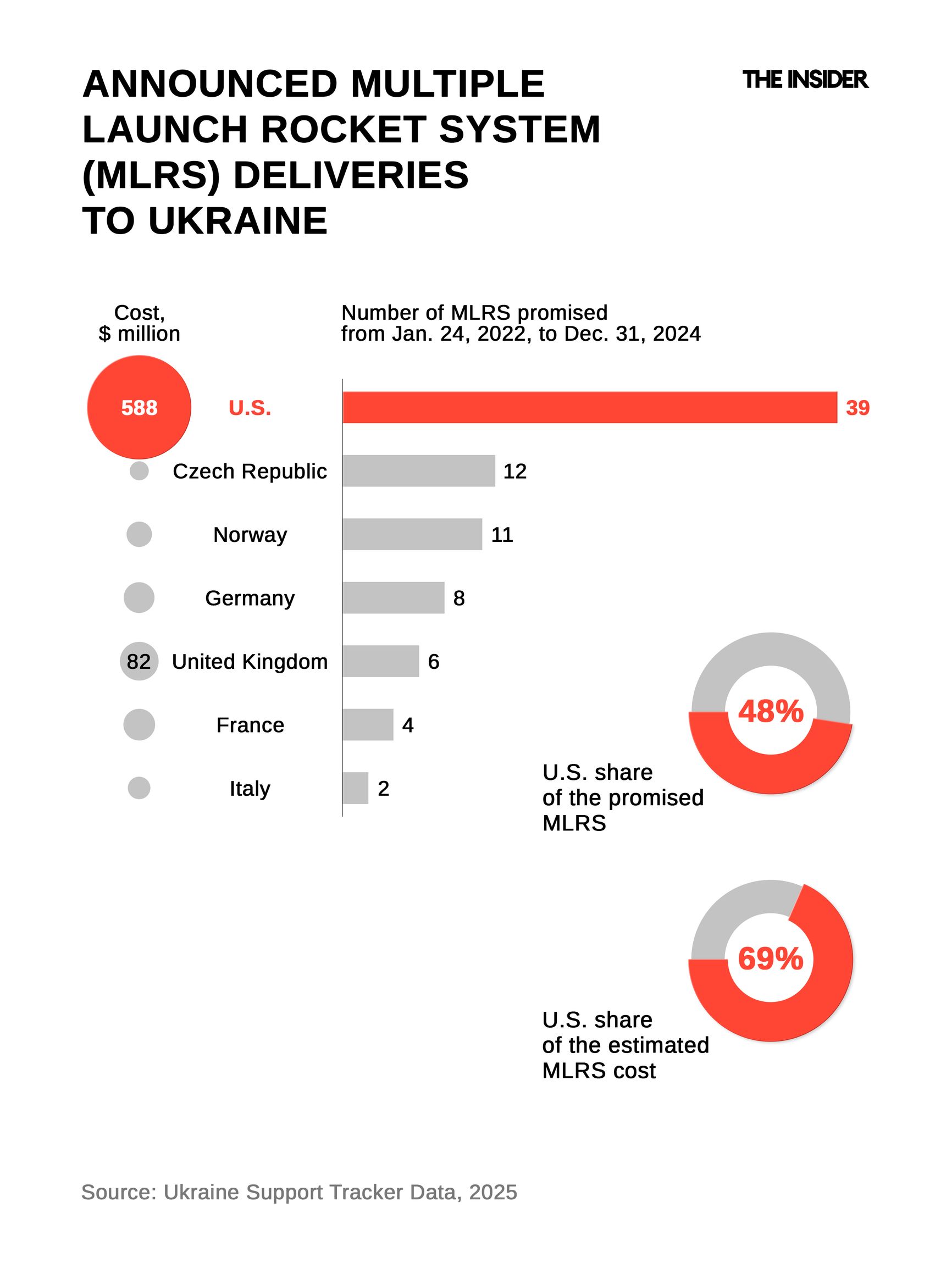

Still, there are areas where U.S. assistance is crucial. American HIMARS make up nearly half (39 out of 82) of the multiple-launch rocket system (MLRS) units sent to Ukraine and account for nearly 70% of the total value ($588 million out of $857 million). For a long time, HIMARS were the only means available to Ukraine for long-range precision strikes against Russian forces — even if the U.S. banned their use on internationally recognized Russian territory. Ukraine remains entirely dependent on U.S. for ATACMS missiles and for ammunition supplies for HIMARS, some of which have already run out. For now, future deliveries appear limited to pre-contracted volumes within USAI.

In the air defense category, the U.S. has supplied only 17 out of 77 total systems, valued at $1.5 billion out of $9.1 billion, and it lags far behind Germany in total contributions. However, U.S. aid is actually most critical in this sector, as only the Patriot air defense system can intercept Russian ballistic missiles, and only U.S.-made interceptors are capable of neutralizing these threats. European SAMP/T systems also have ballistic missile interception capabilities, but their effectiveness in this role remains a subject of debate among military experts.

As for other categories of military assistance, the most significant portion of American supplies is evident in the delivery of armored fighting vehicles, including MRAPs, as well as engineering and other specialized equipment. The relatively modest scale of U.S. aid only highlights the vast reserves of military hardware available in the United States — something that cannot be said for Kyiv’s European allies.

According to The Military Balance 2025, the U.S. arsenal includes 2,640 Abrams tanks of various modifications in active units, with an additional 1,500 in storage. To date, only 31 units have been supplied to Ukraine. The U.S. fleet of Bradley infantry fighting vehicles comprises 2,285 active units and more than 2,000 in storage, of which 352 have been allocated for Ukraine. Meanwhile, out of the 2,600 F-16 fighter jets in service with the U.S. and allied nations, not a single aircraft has been provided to Ukraine.

The U.S. arsenal includes 2,640 Abrams in active units, with an additional 1,500 in storage. To date, only 31 have been supplied to Ukraine.

Over the past three years of war, the United States has supplied the Ukrainian army with close to 4.4 million artillery shells of key calibers: 3 million of 155mm rounds, 1 million of 105mm rounds, 400,000 of 152mm rounds, and 40,000 of 122mm rounds. No other country has delivered comparable quantities, though, for example, under the “Czech Initiative,” Ukraine received 1.6 million artillery shells, including 500,000 of the 155mm caliber.

For comparison, during the same period, North Korea reportedly shipped around 8 million shells to Russia — nearly twice the number the U.S. has provided to Ukraine.

What will happen to the frontline without U.S. aid?

During their now-infamous meeting at the White House, Donald Trump repeatedly told Volodymyr Zelensky that without American support, Ukraine had no “cards” left. Following the suspension of U.S. aid, The Wall Street Journal, citing current and former Western officials, reported that without continued American assistance, the AFU could sustain the current intensity of fighting until at least this summer. Ukrainian sources provided an even grimmer forecast to The Financial Times, estimating only 2–3 months.

However, Ukraine's military has already endured periods without U.S. aid. In the early months of the full-scale Russian invasion in the spring of 2022, when the West feared that help for Kyiv would lead to “escalation,” and again from October 2023 to April 2024, when congressional gridlock delayed funding approvals, the AFU operated without fresh U.S. assistance. The latter blockage was led by Trump-aligned Republicans in Congress. A review of military aid packages under the Presidential Drawdown Authority (PDA) and the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative (USAI) clearly shows a steady decline in U.S. support following Ukraine’s unsuccessful counteroffensive in the summer of 2023, culminating in a total halt by early 2024.

It was precisely during the autumn and winter of 2023–2024 that the Russian military fully seized the initiative on the battlefield, launching a slow but nearly uninterrupted offensive in Donbas, which continues to this day. The failure of other Western allies to promptly fill the gap left by U.S. assistance also played a role. In the second half of 2023, European partners sent even fewer supplies than they had earlier in the year, back when Ukraine was preparing for its counteroffensive.

In other words, during the period of halted U.S. aid, the Kremlin managed to weaken Ukraine’s defenses to such an extent that only in recent months have stabilization efforts by the AFU succeeded in halting the Russian advance toward Pokrovsk and Myrnohrad. However, even the limited territorial gains Russia has achieved — advancing about 50 kilometers in depth on the most successful axis at the cost of approximately 100,000 casualties — allow Putin to enter peace negotiations from a position of strength.

The halt of U.S. aid to Ukraine in the fall of 2023 helped the Kremlin seize the initiative on the battlefield.

When U.S. Vice President J.D. Vance persistently urged Zelensky to show “respect” at the Oval Office and “thank” Washington for its help, he likely overlooked the fact that it was Trump and his allies who effectively created the resource shortages that prevented Ukraine from changing the course of the war in its favor — or at least returning to a position of strategic stalemate.

With the current U.S. administration seemingly unwilling to push new financial support for Ukraine through Congress, the critical question is whether the AFU will face a complete cessation of military aid at some stage in peace negotiations — dictated by Trump’s unilateral decision — or whether assistance will merely gradually dwindle as pre-existing contracts signed under Biden's presidency are fulfilled.

During the winter of 2023–2024, the ratio of artillery fire between the two sides was estimated to favor the Russian side by a factor of ten to one. However, even if U.S. supplies were to be entirely cut off, such an extreme disparity is not expected to recur, thanks to increased European production and purchases from third-party countries. Additionally, since the AFU is now primarily engaged in defensive operations, artillery functions are increasingly being replaced by FPV drones and mines, the production of which does not depend on U.S. support.

According to military analysts, Ukraine needs 75,000–90,000 artillery shells per month for defensive purposes and 200,000–250,000 for major offensive operations. European manufacturers plan to produce 2 million artillery rounds in 2025 — which should more than cover Ukraine’s defensive needs.

However, without U.S. aid, equipping new brigades and restoring the combat capabilities of existing units will become significantly more difficult — a problem that emerged even before Trump returned to the White House. In September 2024, Zelensky admitted that the military assets received from Kyiv’s international partners were insufficient to fully equip even four of the AFU’s 14 newly formed brigades. As a result, the Ukrainian military has had to divert reserves for immediate operational needs while Trump’s allies in Congress block additional aid packages. Now, Kyiv’s primary hope lies in European financing, which could include funds allocated for purchasing weapons from the U.S. itself.

Without U.S. aid, equipping new AFU brigades and restoring the combat capabilities of existing units will become significantly more difficult.

Certain categories of American military supplies remain virtually irreplaceable — especially ballistic missile interceptors, long-range precision-guided munitions, and aviation and artillery weapons systems. Maintaining combat readiness for previously delivered equipment and communication networks, particularly access to Starlink, could also become problematic if restrictions were imposed.

Yet even in the worst-case scenario, Ukraine is unlikely to face a total battlefield collapse. The reason is simple: the U.S. share of Ukraine’s current military supplies is estimated at 20–30%, while domestic Ukrainian production, according to different estimates (1, 2, 3), is approaching — or has already reached — 50%. Ukraine’s war effort will become more challenging without American support, but it will not come to an abrupt end.