Although all Ukrainian refugees in Russia have legal entitlement to doctors, free medicines, and OMI [obligatory medical insurance] policies according to current Russian law, in reality, their access to healthcare largely relies on the assistance of volunteers. The volunteers have established an alternative system of medical consultations, purchasing medication for refugees, escorting them to private clinics, and sometimes arranging treatment overseas. Without the support of these volunteers, thousands of refugees, many of whom hold Russian passports, would be left to manage their health needs independently.

Content

A stranger in a strange land

Parallel system

Theory and practice

Simply Russia

Anatoly Bukhtiyarov, the accordionist in Donetsk, was a well-known fixture and, along with his drummer Nikolay Gladkov, they were collectively referred to as the Grandfather Rockers. The duo gained popularity during peacetime, but they remained in the area even after the hybrid war broke out. In recognition of their contributions to cultural life, they were even bestowed with some form of medal by the self-proclaimed DNR. Nikolay Gladkov did not survive long enough to witness the full-scale invasion, and despite his fame, Anatoly Bukhtiyarov did not receive any protection. In the autumn, the famous musician from Donetsk was unexpectedly discovered in the district center of one of the national republics of the Russian Federation.

Volunteer Diana Ramazanova, who tried to save the pensioner, is reluctant to even name the region:

“Maintaining good relations with the administration is crucial for me since I have hundreds of people under my care. As for how we located Anatoly Bukhtiyarov, it happened when one of our volunteers delivered a winter hat to a woman staying at the TAC [temporary accommodation center]. The woman mentioned an elderly man in one of the rooms who required assistance, which led us to discover that the person in question was none other than the rock musician, Anatoly Bukhtiyarov.”

Prior to the invasion or at the start of the war, he and several other elderly individuals from the unrecognized republics under Russian control were evacuated. At first he was in good health. He used to entertain people on the streets by playing the accordion and used the money he earned to purchase candy and ice cream for the children at the TAC. However, he was hospitalized unexpectedly and returned bedridden. Diana is still uncertain about the circumstances that led to his hospitalization.

“Our volunteer was informed confidentially while in the hospital that he had prostate cancer along with some complications. However, he was transferred to the palliative care ward designated for individuals with neurological issues, despite the fact that he remained completely lucid. On New Year's Eve, we presented him with a Walkman that we had filled with music. When the volunteer gave him the gift, she offered to upload more tracks if needed. The old man charmingly responded, 'I'd like anything that a woman likes.'”

Diana and her fellow volunteers were making arrangements to transport the pensioner to Finland for medical treatment, but unfortunately, he passed away before they could do so. Similar to numerous other Ukrainian refugees, the old rock musician was unable to receive standard medical care in Russia.

A stranger in a strange land

Vladimir Igorevich, another elderly refugee born in 1944, was a Russian national who had been residing with his relatives in the vicinity of Kharkiv. However, during the evacuation, they became separated. While his wife and son were able to flee to Germany, the pensioner went missing. As a stroke of luck, he was located in a nursing home within the Belgorod area, where he was discovered to be in poor health and bedridden with bedsores and a fractured femoral neck, without any appropriate medical attention.

The volunteers from St. Petersburg purchased a train ticket for the man and arranged for a nurse to accompany him during the journey. Upon his arrival at the train station, he was met and escorted to one of the hospitals. Diana Ramazanova says that medical facilities in the border regions are overburdened with injured people and refugees. Therefore, the volunteers aim to transport sick civilians to either St. Petersburg or Moscow for treatment:

“But after a few days Vladimir Igorevich was kicked out of hospital. The doctor told us that he couldn't keep a patient whose documents weren't in order.”

The fact is that the old man had lost his Russian passport while leaving the territory occupied by the Russian army. The volunteers had pictures of the lost documents, but the officials and doctors were not convinced.

Vladimir Igorevich had to be placed in a ward that required payment. Despite receiving treatment that was not particularly effective, it was quite costly. Diana says even a basic blood test cost 2,000 rubles ($27).

Once the pensioner received some medical attention, the decision was made to transport him to his family via Estonia, as it was the most straightforward option. It only took six hours by car from St. Petersburg to the border. A commercial ambulance was hired to transport him, with another team awaiting his arrival on the other side of the border. Throughout the journey, Diana continued to keep in contact with the attendants:

“His blood pressure was skyrocketing, and I even offered to cancel and pay for everything, to stop him from being transported. The problem was that Estonia recently tightened its borders, making it difficult for Russians to enter the country. In the first months of the war, they let almost everyone in, but then the processes slowed down. So, they didn't want to let Vladimir Igorevich in, given that he had lost his passport. They kept him at the border for hours. I was on the phone the whole time. And right in the middle of the conversation his heart stopped. They started resuscitating him, took him to the nearest hospital, but they couldn't save him.”

Diana's voice becomes emotional as she shares her experiences, but she also has stories that end on a positive note, despite their tragic beginnings. One such story is that of Victoria and Vladimir Shishkin, who were in the Mariupol maternity hospital during the infamous Russian shelling. Victoria sustained shrapnel wounds to her abdomen, resulting in the loss of their baby, while Vladimir had to undergo a leg amputation.

Victoria Shishkina. Photo: Elena Lukyanova specially for ASTRA

At first Diana didn't even know what she was getting into:

“In May, a woman approached me at a TAC in St. Petersburg seeking assistance for her sister and brother-in-law. According to her, her brother-in-law was experiencing some leg issues. We organized their transportation from Taganrog to Rostov-on-Don, and then to St. Petersburg through remote means. However, during the two-day train journey, we were unaware of the severity of Victor's condition. His temperature rose to 39 degrees, and he was at risk of dying due to an infection in his leg compounded by his terrible mental state.”

The man, of course, had Ukrainian documents. But medics from a commercial ambulance forced the hospital to admit him. There the doctors stopped the infection, found additional shell fragments in his back, though they did not remove them. Meanwhile, Diana contacted a German hospital:

“He was promised he would receive a high-quality prosthetic there. Eventually, we managed to facilitate their departure, and Victoria and Vladimir were allocated a private residence in Germany. Vladimir underwent surgery to extract fragments from his injured leg, and his leg is currently being prepared for prosthetic placement. Recently, Vladimir sent me a picture of himself, Victoria, and a teddy bear sitting at the table.”

Victoria and Vladimir Shishkin, photo from personal archive specially for ASTRA

Parallel system

During the war, concerned Russians built an entire infrastructure to receive refugees from Ukraine, including a special Telegram chat room for doctors. At first it was just open correspondence, where the sick people contacted each other, and the doctors responded. Then, when there were more refugees, they made a chatbot. Now appeals are automatically distributed among doctors of different specialties. For example, Evgeniya, a pediatrician from Moscow, together with several other colleagues, helps sick children:

“Whoever's available, answers first. The region doesn't matter – consultations are provided remotely.”

She devotes approximately one hour daily to this volunteer work. The early months of the war posed significant challenges, with a massive influx of refugees and numerous children suffering from respiratory illnesses and intestinal viruses due to overcrowded living conditions. The most pressing needs were for psychologists and dentists. Following weeks and months of residing in basements without access to proper hygiene facilities, many children reported experiencing toothaches.

There was a massive influx of refugees with numerous children suffering from respiratory illnesses and intestinal viruses due to overcrowded living conditions

They did not have OMI policies, and medical institutions often refused to help them. According to Evgenia, decisions were made not at the regional level, but at the level of a particular clinic:

“In Rostov-on-Don, one surgeon would be willing to treat you, cut open an abscess, prescribe medication, and would do so without requiring any documents. Meanwhile, another surgeon may refuse to speak with you unless you possess an OMI policy. Fortunately, the situation has improved as medical institutions have been made aware of their obligation to assist refugees.”

Rheumatologist Irina, also a Muscovite, works in a TAC care group in one of the neighboring regions. According to her, there is a big difference in terms of medical care even among various TACs:

“There are only three TACs there. In two of them people get all medicines if they have a doctor's prescription. Even expensive ones. A nurse is present all the time, a doctor comes twice a week. In the third TAC, a doctor comes only if called on purpose. And the patients are not even provided with painkillers. Elderly people live there, many of them with poor health.”

Irina helps them procure medications. She collects lists from refugees, excludes all kinds of drugs with unproven efficacy, such as “immunity pills,” popular in the countries of the former Soviet Union, and places the order.

Pediatrician Evgeniya admits she has paid for medications and tests for the people under her care:

“We had a boy diagnosed with epilepsy who had gone an extended period without receiving anticonvulsants. Although the family had a prescription, it originated from Ukraine, making it difficult to acquire the medication in Moscow and send it to the child. In another instance, a girl was suffering from pyelonephritis, a non-life-threatening condition that necessitated prompt antibiotic treatment. To proceed with therapy, she needed to undergo a urinalysis, which the clinic declined to perform. We had to pool resources and pay for the test ourselves.”

Irina, a rheumatologist, provides assistance via Telegram chat to individuals with autoimmune diseases, which is her primary area of expertise. Additionally, she occasionally treats patients at one of the two commercial clinics where she practices. The first clinic is relatively costly, but sometimes Irina will waive consultation fees for certain patients, including refugees. Typically, this privilege is only extended to friends and family of clinic staff, but Irina is willing to make exceptions. At the second clinic, we negotiated an arrangement whereby Irina's consultations were free for refugees, and all other services were provided at a 50% discount. Moreover, Irina usually covers 50% of the fee out of her own pocket.

There are specialists and private clinics available for nearly all medical fields. During the year of the war, a parallel healthcare system has been established in Russia to provide medical services to civilians from regions that had been overtaken by Russian troops.

During the year of the war, a parallel healthcare system has been established in Russia to provide medical services to refugees

Theory and practice

Olga, a lawyer from one of the charitable organizations helping refugees, explains that legally these people have no right to refuse medical care:

“Last summer, Russian government decree 1134 was amended to ensure that individuals arriving from any region of Ukraine are entitled to emergency and urgent medical care, as well as free medication through state programs. The sole requirement is a doctor-confirmed diagnosis, which entitles the individual to receive the necessary medication. However, in practice, patients often do not receive all the necessary medicines. For example, cancer patients may receive chemotherapy drugs, but not painkillers, including simple medications such as Nurofen. Individuals with diabetes may receive insulin, but not glucose meters and test strips. Typically, individuals are required to make an appointment with a doctor, obtain a prescription, and use it to purchase medication at a discounted rate from a state pharmacy. However, the process is different for refugees: they visit the clinic, request a prescription, are denied a discount, file a complaint, return to the clinic, and often receive some medication without a written prescription. While the patient is temporarily provided for, it rarely becomes a regular benefit.”

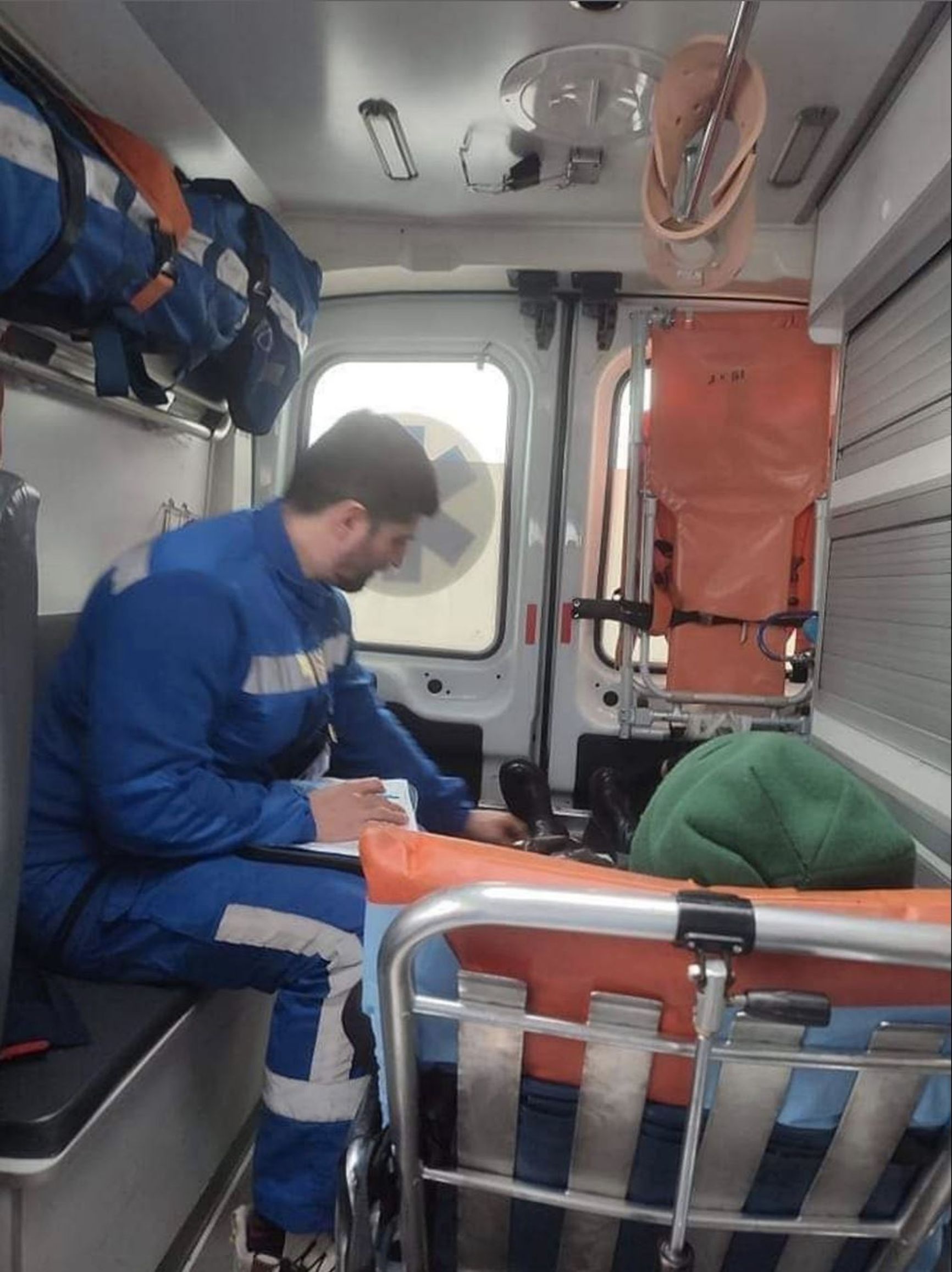

The cancer patient Diana picked up from the train station

At present, a refugee receives an OMI policy together with the right to temporary asylum. And there is no need to give up the Ukrainian passport in exchange for this. Sometimes applying for Russian citizenship even complicates matters, Olga says:

“As long as a person has temporary asylum, their medications are covered by the federal budget. However, once they obtain a passport, the responsibility for funding their medication falls on the region. Sometimes patients are turned away from the polyclinic because the regional budget has insufficient funds to cover their medication. This should not be the patient's concern, as the region can request the necessary funds. However, in some cases, the region is reluctant to do so. In such cases, filing complaints with the regional health agency or Roszdravnadzor [Russia's health supervision authority] is often the only way to receive necessary medical care. The problem is that the individuals who require these medicines are unwell and confused, having come from a war-torn area, and are simply too exhausted to fight for their rights. A lot of them have resigned themselves to their fate, suffering in silence or in excruciating pain.”

However, in reality, things are much more complicated than when you view them theoretically. To illustrate, consider the case of a 65-year-old woman, Maria Petrovna (name changed), who is under the care of the same foundation. She only became aware of her HIV infection after undergoing testing as part of the application process for Russian documents.

Maria Petrovna, a 65-year-old who is under the care of the foundation, only became aware of her HIV infection because of the war

The elderly woman, who doesn't belong to any high-risk category, was genuinely shocked. However, she received a ray of hope as a private clinic in Moscow generously provided her with three months' worth of medication as charity.

But obtaining a Russian passport and an OMI policy proved to be a more extended process. In December, she reached out to the foundation for assistance. Anna, a volunteer who provided her aid, mentioned that the elderly woman's primary concern was the discontinuation of her antiretroviral therapy:

“The treatment is such that once initiated, discontinuation is not an option. However, the paperwork involved in Russia is time-consuming. We procured two more months of medication for her. In the interim, Maria obtained a passport, but she still couldn't receive free treatment in Moscow as she didn't have permanent registration.”

The woman hails from a region in Eastern Ukraine, which Russia considered as its new territory after annexation. Consequently, the Moscow infectious diseases hospital attempted to transfer her for treatment to her “place of residence.” The pensioner had to submit a separate request to the Moscow Department of Health. Only after a month had elapsed, she received the free medications she was entitled to.

The foundation has its private medical chat room. Remarkably, nearly every other assistance request involves diabetes. A recent case in point is a 58-year-old Ukrainian man with diabetes who had already lost his toes due to a related complication known as “diabetic foot.” Despite being referred to an endocrinologist in another city by a district polyclinic in New Moscow, he was not prescribed medication although his diagnosis was confirmed. Instead, he was advised to reapply for disability as per Russian rules. The process is a tedious one, and given his old age, trips to different cities for consultations are quite challenging. Volunteer Katya, who oversees the man, cited budgetary constraints as the root cause of the issue:

“People with disabilities are entitled to receive payment for diabetes treatment from the federal budget, whereas people who only suffer from diabetes and have no disabilities are supported by the regional budget. In theory, the region could seek funding from the Ministry of Health in Donetsk and request a transfer of funds to Moscow to cater to this individual's needs. However, I am unaware of any instances where this approach has proved successful.”

As a result, Katya had to purchase medicine, insulin injection syringes, and test strips for the man for a month, which altogether cost 14,000 rubles ($190). The money was donated by the foundation and spent on stuff that should have been provided by the state for free. Unfortunately, such cases are abundant. Diabetics struggle to acquire insulin, and people with exacerbated peptic ulcers face difficulties obtaining gastroscopy. For instance, Katya recently dealt with a 70-year-old man from one of the regions recently annexed by Russia, who lost his vision after being trapped under rubble. Katya spent a considerable amount of time seeking a healthcare professional who could perform a relatively rare eye examination for him:

“I shared his story with everyone, hoping that people would be moved to help. However, no one offered assistance without payment. During the MRI, doctors identified a “stroke in progress,” a rare condition that can be challenging to detect early on. We were at the federal neurology center, and the doctors suggested that we step outside and call for an ambulance. It was December, and the weather was cold and rainy, and we were left with a blind elderly man who had suffered a stroke and was asked to wait. We decided to pay for a neurologist's consultation right at the center for an additional 3,000 rubles ($37), after which the doctor took pity on us and called an ambulance to her office. However, if my client had been a Russian citizen, he would have most likely been forced to step out into the street and call for an ambulance in the same way.”

Simply Russia

Some refugees were left without assistance, not because of their complicated status but merely because they were in Russia. In numerous settlements where TACs are located, good doctors were hard to find, even before the war. For instance, rheumatologist Irina had to take her patient to Moscow, just to have him examined by a decent neurologist. Similarly, pediatrician Evgeniya had to cover the cost of a psychiatric consultation for a young refugee.

“Decent child psychiatrists are scarce in the regions, causing problems for children in need. In one case, a child received free assistance, but the doctor provided an unreasonable diagnosis of mental retardation, which the child clearly did not have. Fortunately, a good doctor in Moscow was found, who provided a competent diagnosis of ADHD. However, this issue is not unique to refugees, as a child from a Russian family could face the same situation.”

On the other hand, according to rheumatologist Irina, a few older people from small towns in Ukraine, after a long time, got the opportunity to consult proper doctors; it was volunteers from Moscow who found those doctors and paid their fees.

“People are trying to get their teeth fixed, their eyesight fixed. A lot of people say: “We were not seeing doctors before.” Yesterday we collected 80,000 rubles ($1000) to pay for a woman's dentures. And then she wrote she didn't want them, she wanted different ones, which cost 12,000 ($150) more.”

Irina admits she doesn't like all of her current clients on a personal level. Some of them are uncooperative and ungrateful towards medical professionals, while others have openly expressed their belief that they would “spend only three days in evacuation and then become a part of Russia.” Volunteers who assist refugees come from various backgrounds, some of them with anti-war views, while many of the refugees who came to Russia hold pro-Russian sentiments. Some refugees can also be confrontational. But despite these differences, the volunteers recognize that many refugees are sick and vulnerable, and they are the only ones who can provide help.

Volunteers who assist refugees come from various backgrounds, some of them with anti-war views, while many of the refugees are pro-Russian

Irina explains it this way:

“Yes, they are often quite ignorant. Yet we can't segregate them. By helping all of them, we as volunteers are also helping ourselves. In the future, our children will ask us what we were doing in 2022. What will I tell them otherwise?”