Interim Syrian President Ahmed al-Sharaa has been working to rebuild ties with the West since the mid-2010s, when his anti-Assad Islamist force was still based in Idlib. Back then, al-Sharaa’s outreach allowed his faction to avoid coming under U.S. airstrikes — unlike nearly all rival groups, which were dismantled. Such diplomatic efforts also helped him secure Turkey’s support in the fight against Bashar al-Assad’s regime. Since coming to power in December 2024, al-Sharaa has pursued engagement with nearly all regional and international actors simultaneously — including both Turkey and Israel. However, al-Sharaa’s willingness to find common ground has sparked discontent among his own supporters. Some are now considering defecting to more radical groups, such as the Islamic State and al-Qaeda, both of which are reportedly seeking to establish contact with critics of the interim government.

Adapt and survive

Syria’s new interim president, Ahmed al-Sharaa, has been laying the groundwork for engagement with the West since 2016, when he began steering his al-Nusra insurgent group towards a split from al-Qaeda. Up until then, al-Sharaa’s group had functioned as al-Qaeda’s Syrian branch. In the mid-2010s, however, it began seeking to reach an understanding with regional and international actors, first and foremost Turkey. Those were the years when Russian intervention in Syria was turning the tide in favour of the Assad regime and the U.S. air campaign against the Islamic State threatened to engulf al-Nusra itself.

Ahmad al-Sharaa, then known by his nom de guerre Abu Mohammad al-Julani, announcing Al-Nusra's split from al Qaeda in 2016.

That split lost al-Sharaa the support of thousands of al-Qaeda loyalists, who turned against him. However, he clearly thought that without an alliance with Turkey — and also without the tolerance of the U.S. — his group would not survive the very challenging time that lay ahead. His new organisation, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), held discussions with U.S. and British intelligence, according to internal sources, and thanks to the separation from al-Qaeda it did in fact earn an exemption from the air campaign against Islamist movements.

That was an act of supreme pragmatism, but it allowed HTS to maintain its strength at a time when all the main competing organisations were being smashed to pieces — whether by the U.S. or the Russians. The fall of the Assad regime at the end of 2024, however, was less the result of the military proficiency of HTS and its allies than of the Assad regime rotting from within. It is clear that even al-Sharaa did not expect to find himself in power — at least not as quickly as it happened.

It is clear that even al-Sharaa did not expect to find himself in power — at least not as quickly as it happened.

Many believe that HTS has been sharing intelligence with the U.S. about the location of al-Qaeda and Islamic State members, who were regularly hit with precise airstrikes, for years. If that was the case, it was done covertly and did not arouse too much controversy within HTS.

However, since HTS came to power in Damascus, al-Sharaa’s extreme pragmatism has come into the open. He has sought Western approval, has reached out to Israel, has reached an agreement with the mainly Kurdish and leftist SDF, has agreed to negotiations with Russia over its bases in Syria, has offered peace to Iran, and has even suspended the implementation of Islamic Law (which was being applied in the HTS stronghold of Idlib prior to the change in regime in Damascus). Some of these offers might have been made in the expectation that they would be rejected. For example, Russia was offered the chance to keep the bases in exchange for returning Bashar al-Assad and other dignitaries of the former regime, a service Moscow is highly unlikely to render.

A debatable pragmatism

Overall, this pragmatic approach might well be the only viable one for a new regime that is dependent on Turkish goodwill, has no money, and counts on limited manpower to control the country (there are probably no more than 30,000 armed men under al-Sharaa’s direct control). Most Sunni Arab armed groups in Syria have pledged support to the new government, and after the March 11 agreement with the SDF, a kind of de facto federal approach has been agreed with the Kurdish militias too.

Interim Syrian President Ahmed al-Sharaa, right, shakes hands with Mazloum Abdi, commander of the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces in Damascus following the signing of an integration agreement.

Photo: AP

It is far from clear, however, how solid all these deals are. One HTS cadre said in March that he did not think the SDF deal had really been cleared with the Turks and their Syrian National Army proxies. Al-Sharaa rushed to reach an agreement after coming under heavy Western criticism after his armed forces massacred hundreds of civilians in Latakia and Tartus in early March.

More importantly, the membership of HTS itself, and of most of its allies, is still made up of committed jihadists, many of whom are unhappy about some or all of al-Sharaa’s policies. The negotiations with Russia over its bases elicit some of the most negative comments, acknowledges an HTS commander in Idlib, contacted in February. He says most of the ranks-and-file fighters believe that the Russians should be told to exit Syria without delay.

Al-Sharaa’s friendly approach to the U.S. is less controversial, as the militants understand that the U.S. did not target them during its air campaign — which remains ongoing. They must have also noticed the favourable press coverage from some U.S. media outlets.

Al-Sharaa’s friendly approach to the U.S. is less controversial, as the militants understand that the U.S. did not target them during its air campaign.

Iran is a much more controversial topic. Tehran was just offered normal diplomatic relations, and unsurprisingly, its relations with Syria worsened rapidly, sparing al-Sharaa any need to justify his initial opening to his base. The new government believes Iran and Hizbollah are reaching out to various groups to re-mobilise them against the new regime — it is they who Damascus accuses of being behind the clashes in Latakia and Tartus that started on March 6. Border clashes with Hizbollah are quite frequent.

Possibly the worst criticism derives, however, from Al Sharaa’s soft approach to Israel — the more so as the latter not only occupies Syrian land, but also seeks to establish direct links with Syrian communities, such as the Druze in Suwayda. Moreover, sympathy for the Palestinians is very widespread among the ranks of HTS, where Hamas also enjoys a high level of support. Critical voices within HTS, such as an officer in the new ministry of defence contacted in February, believe that the majority of the members of HTS oppose the current approach of al-Sharaa towards Israel. However much hatred might be there for Iran, they believe that Israel should get no better treatment.

Possibly the worst criticism derives from Al Sharaa’s soft approach to Israel — the more so as the latter not only occupies Syrian land.

Relations with Turkey are not problematic for now — unsurprising given the role that Ankara has played in enabling the success of HTS. Nevertheless, HTS members still say that they do not want any foreign country to interfere in their internal affairs. In reality, Turkey has huge leverage, as it not only controls the largest armed force in Syria — the Syrian National Army — but also hosts over 3 million Syrians. Maintaining friendly ties with Turkey is essential for Syria’s economic recovery. Most HTS members are worried about the extent of Turkish influence, but they are ready to put off discussion of the issue until the new regime has consolidated. The allies of HTS are divided between Turkish proxies and groups that are outright hostile to Turkey, making a balanced position hard to find.

Another problem that al-Sharaa has to face stems from the generous deal struck with the Kurdish SDF earlier this month. Some of the groups in his coalition government still do not see eye-to-eye with their president on that front.

Criticism from within

Keeping foreign states happy while maintaining the satisfaction of his own base is going to be hard for al-Sharaa. Many of his allies come from the Islamic State, having joined following the fall of Raqqa. With the exception of the younger recruits, most of the rest come from al-Qaeda, as does al-Sharaa himself. It is not too far-fetched to speculate that disgruntled members might consider going back.

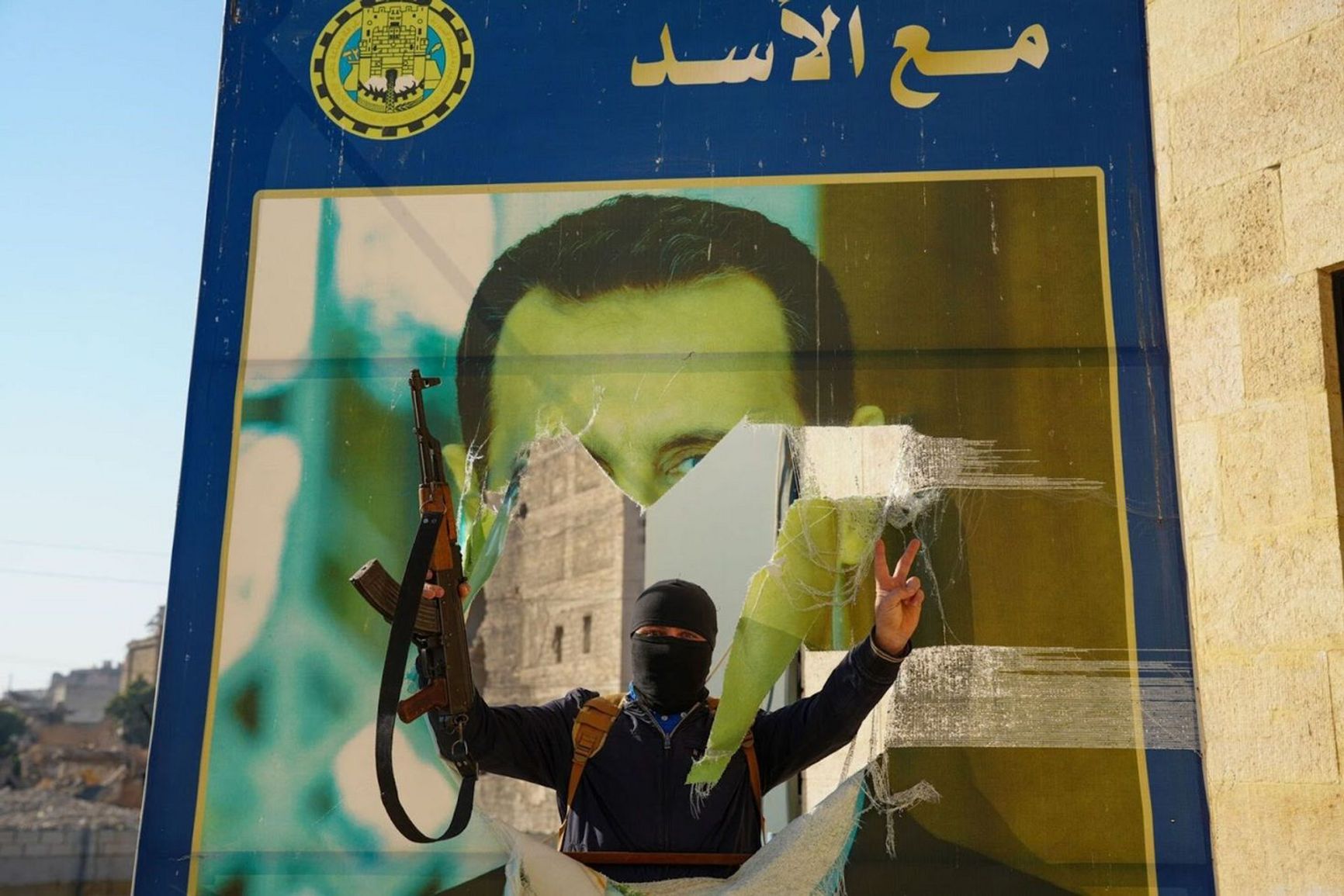

Syrian rebels tear down a poster of Bashar al-Assad in Aleppo on Nov. 30, 2024, following the city’s capture in a surprise offensive.

Photo: Rami Alsayed / NurPhoto / Reuters

Al-Qaeda is not seen as a threat for now, and HTS officially claim that the group has largely been crushed, with its minimal remaining presence remaining underground. The Islamic State is known to maintain cells and guerrilla groups in some mountain and desert areas, especially around Raqqa, but its capabilities, too, are assessed as being very low.

Still, according to the aforementioned source in the Ministry of Defence, in the future it is certainly conceivable that the dissidents from al-Sharaa’s young regime might feel attracted by al-Qaeda or Islamic State, who according to some sources within HTS are already reaching out to members.

Al-Sharaa is reportedly worried too, and some senior HTS figures already assume there will be defections. Entire groups, if marginalised and dissatisfied, might consider rekindling links to either global jihadist group. “A small mistake of our leadership and the current interim government will collapse,” says the source in the MoD.

Especially at risk of defection are the movement’s numerous (4,000-6,000) Central Asians, Uyghurs, Chechens, and Daghestanis, who either joined HTS and its allies individually or allied with it as a group. Many of them were in the Islamic State until 2017, and it is very likely that at least some of them retained connections with friends and relatives who are still there.

The same is true regarding past links to al-Qaeda. Some of the Central Asian groups, such as Katibat al Tawhid Wal Jihad, even renewed their pledge of loyalty to the late Ayman al-Zawahiri back in 2019, at a time when they were already associated with HTS. Several other groups never formally broke with al-Qaeda, or else they withdrew their pledge.

Al-Sharaa has attempted to pacify the uneasy Central Asians and the other foreign fighters by issuing Syrian citizenship. He also offered some of them positions in the new Syrian army. Many see al-Sharaa’s offer not only as generous, but as the only viable alternative, arguing that the Central Asians should take whatever pragmatic alternative comes from the leadership and be thankful.

Others, however, still say that this is not what they fought for during long years of war — what they want is the establishment of a “full” Islamic Law regime. They are angry that al-Sharaa has not imposed the hijab on Syrian women and that he decided not to implement the sort of religious regime that existed in Idlib. These Central Asians are also furious over al-Sharaa’s policy of befriending Western countries — especially his refusal to condemn Israel over its occupation on Syrian soil, let alone to take any action. Some even remain committed to global jihadism, a member of the Uzbek group Katibat Imam al Bukhari openly said when contacted in February.

Critics of al-Sharaa’s regime still say that this is not what they fought for during long years of war — what they want is the establishment of a “full” Islamic Law regime.

There is therefore a growing gap between a portion of the Central Asians and al-Sharaa, even if one of these Central Asians critics says that the bulk of the foreign fighters are still willing to give him a chance to rectify his policies over the coming months. Failing that, they would be ready to part ways. For Certainly, he says, both the Islamic State in Syria and al-Qaeda will be happy to welcome back their disgruntled foreign fighters.