The Insider has discovered that Russian customs data for 2025 lack information on shipments in 180 previously reported categories of high-tech goods, mainly in the areas of electronics and industrial manufacturing. Given that importers have not ceased their operations, it appears that data on these shipments is simply no longer being entered into the customs database. By all appearances, Russian authorities are seeking to conceal information about “gray” imports in order to avoid new sanctions against suppliers of critically important goods — primarily those used by the military-industrial complex. But such a move is not cost-free for the Kremlin: with Rosstat data no longer available even to domestic researchers and policymakers, public governance and economic planning will only become more difficult.

Russian authorities have long understood how to conceal data of public significance: for example, the Unified State Register of Legal Entities (EGRUL) has restricted access to information about the owners of “strategically important” enterprises; the Federal Service for State Registration, Cadastre and Cartography (Rosreestr) has closed access to information about the property of corrupt officials; and the Russian State Library has blocked access to the possibly plagiarized dissertations of high-profile officials. However, a new restriction implemented in 2025 marks the first instance of the Russian state directly removing data that materially affect the reliability of official statistics. As The Insider has established, this year the Russian customs authorities stopped recording a significant number of product categories in the centralized database of import statistics.

The full list of items has been published on The Insider’s GitHub.

This appears to be the largest case of deliberate corruption of official records in Russian history

Previously, The Insider reported that Shahed drones supplied from Iran were labeled as “motor boats,” but such cases were isolated incidents. Now, however, goods are neither renamed nor reclassified into other categories — they have simply ceased to be visible.

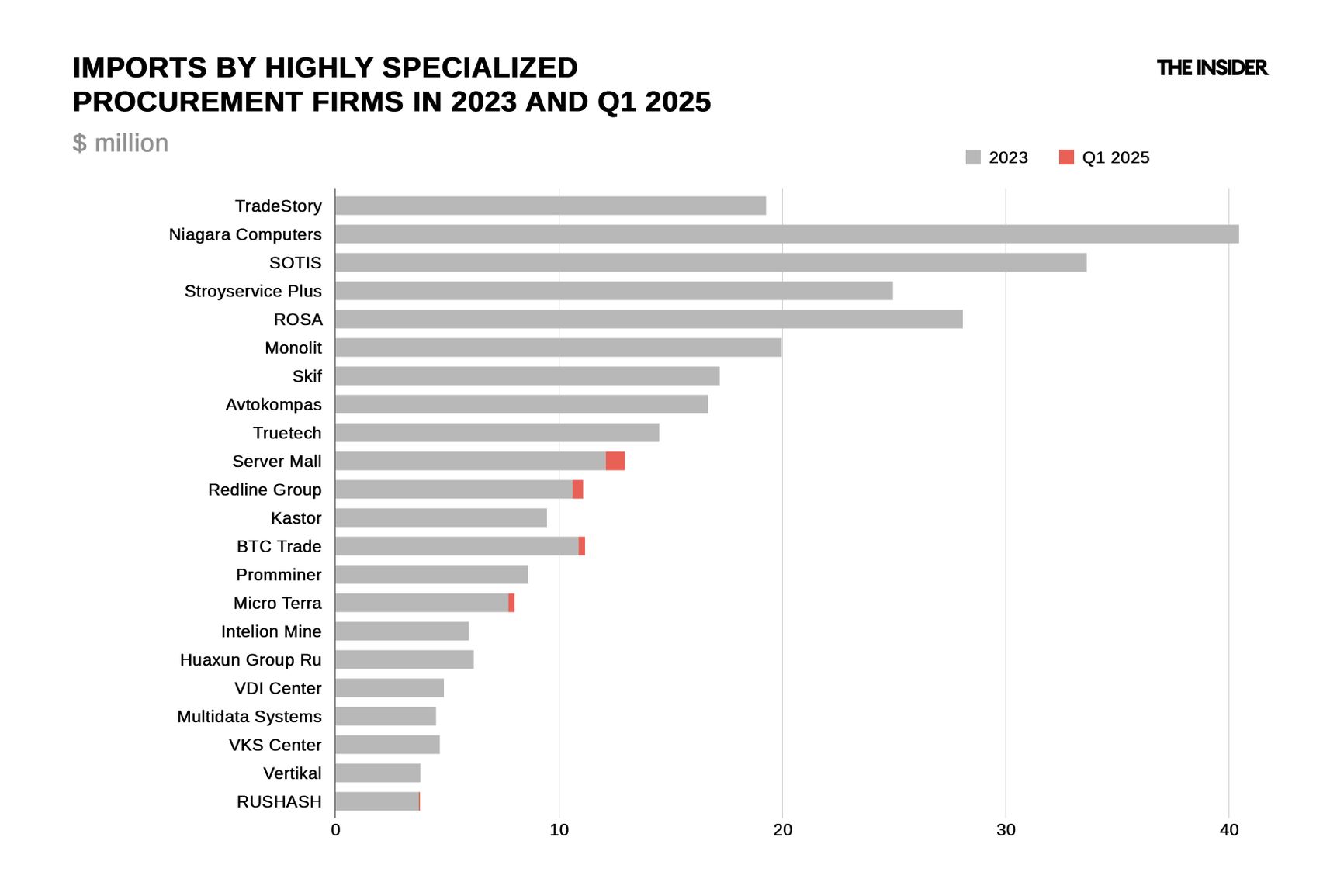

This conclusion is based on a closer examination of companies that previously specialized in a very narrow range of goods, such as microchips. Instead of showing significant turnover in a different product category (as a result of declaring microchips to be something like “matches” or “nails,” for instance), these firms have disappeared from the customs radar altogether.

At the same time, Federal Tax Service data does not suggest these companies are shutting down, ceasing operations, or significantly reducing their turnover.

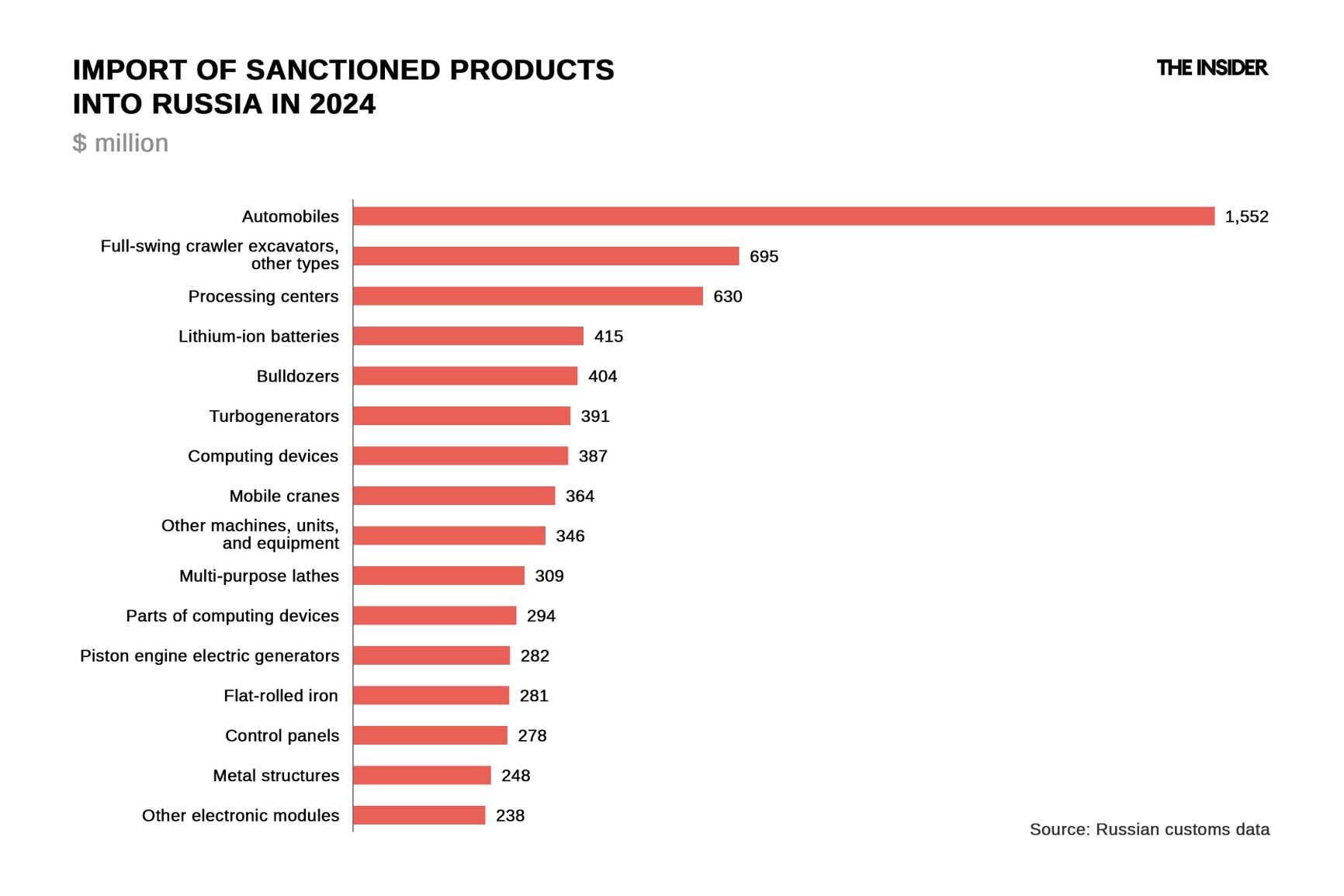

In 2024, Russia imported $22 billion worth of sanctioned goods for machine building, electronics, and metallurgy. And by every indication, the flow did not magically stop when the calendar turned over to 2025.

The full list of items has been published on The Insider’s GitHub.

These goods are used in both civilian and military applications. At the same time, as The Insider has reported, under current conditions even seemingly civilian goods end up being used to further the work of Russia’s military-industrial complex. For example, “lithium-ion batteries” are a key military item, as batteries are primarily needed for drones. As The Insider has been reporting for years, complex foreign goods such as machining centers and lathes are likewise in demand first and foremost from Russian military-industrial enterprises.

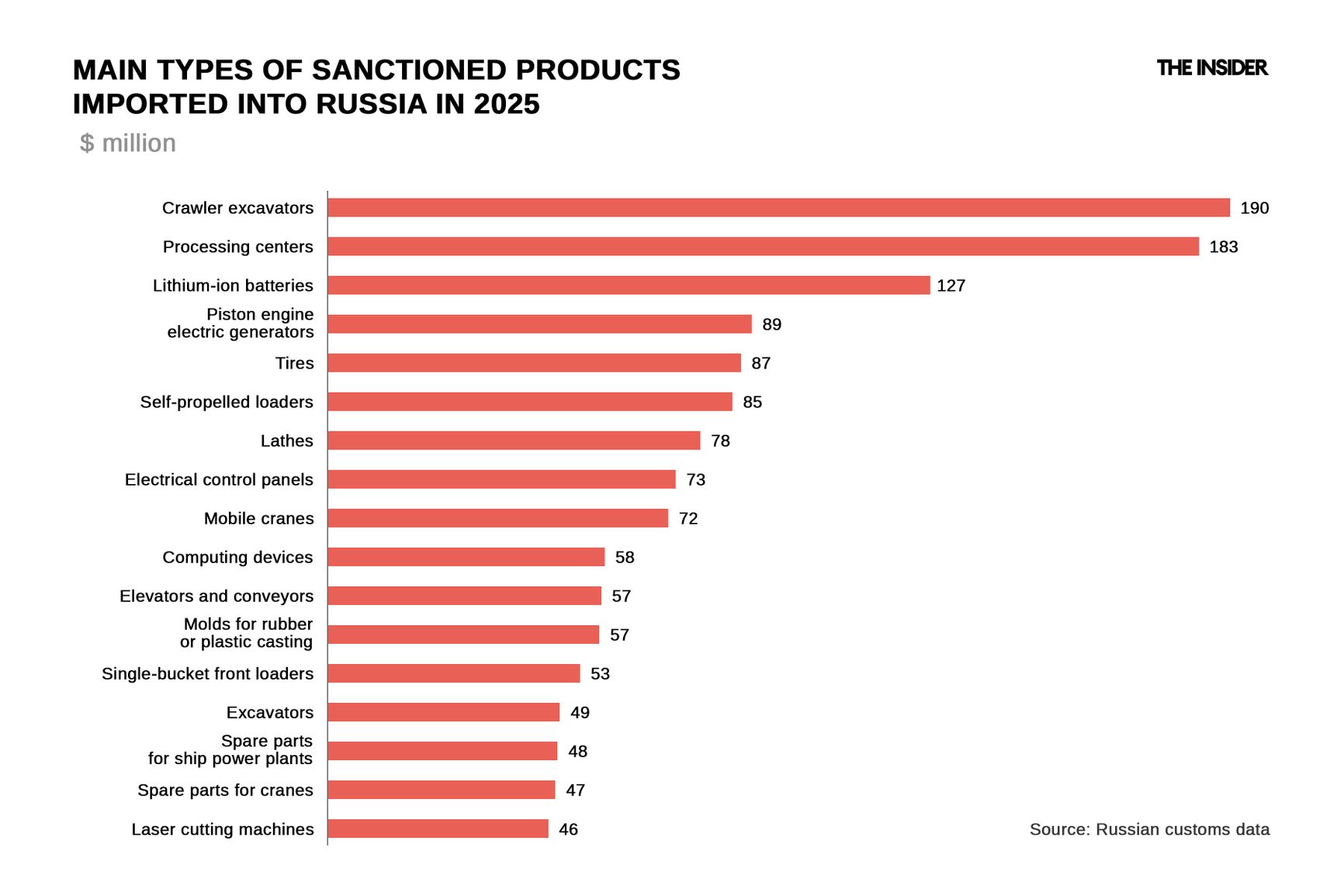

In 2025, the list of leading import items in sectors subject to EU and U.S. sanctions changed significantly. This year, Russian imports no longer include units of computer equipment, routers, integrated circuits, video cameras, electronic components, frequency generators, radar equipment, navigation devices, electric motors, machinery for manufacturing integrated circuits, and many other electronics items. Drilling machines, industrial furnaces, and certain other equipment have also disappeared — a total of around 180 items. On paper, shipments of these goods — all of which fall under restrictions imposed by the EU or the U.S.— currently stand at zero.

The full list of items has been published on The Insider’s GitHub.

However, in the first three months of 2025 alone, Russia imported over $5.7 billion worth of sanctioned goods.

Russia's monthly customs reports suggest that the codes stopped appearing in the “mirror” database at the end of 2024. The Insider also noted three important indicators. First, these changes occurred simultaneously. Second, companies — particularly those specializing in a single product type — continued to operate actively in the market. Third, transactions involving these product types in 2025 are recorded as zero. Taken together, these facts point to a deliberate large-scale data skewing operation within the Russian customs registry.

The infographic below shows a comparison of import turnover for highly specialized companies that previously supplied chips. Had they simply reclassified their goods (whether with permission or under direct instruction from a customs officer), the turnover would have remained roughly the same, given that consumption of these goods has not decreased dramatically.

The full list of items has been published on The Insider’s GitHub.

In all likelihood, when customs documents are filled out for goods with these codes, the information is not saved on the central customs servers. Meanwhile, goods with other codes continue to appear in the database as usual.

Still, there is a potential downside for Moscow in taking such a remarkable step. This concealment may hamper efforts to reasonably analyze or forecast economic activity in the manufacturing sector. As a result, Russian academic institutions engaged in national economic research, government departments responsible for planning and analysis, and the state statistical agency Rosstat (which will yet again face accusations of falsifying data) will all be indirectly affected by this “anti-sanctions” policy.

The full list of items has been published on The Insider’s GitHub.