The ruble has been strengthening for six months, and neither falling oil prices nor an economic recession have managed to knock it off its present trajectory. The rise is being driven by a collection of factors: the decline in imports, the Central Bank’s high key interest rate (despite a recent cut), and the carry trade. On the surface, a strong ruble may seem like a positive indicator. But an overly robust national currency reduces budget revenues and hampers exporters trying to sell their goods. The current situation is unstable, and further fluctuations are inevitable due to domestic economic pressures, increased volatility in the currency market, and possible geopolitical shifts — including the prospect of a ceasefire. Under these conditions, Russian households must be cautious in how they manage their savings.

Content

Why is the ruble getting stronger?

Who benefits?

The cost of a strong ruble

Forecasts for the future

What should Russians do with their rubles?

Why is the ruble getting stronger?

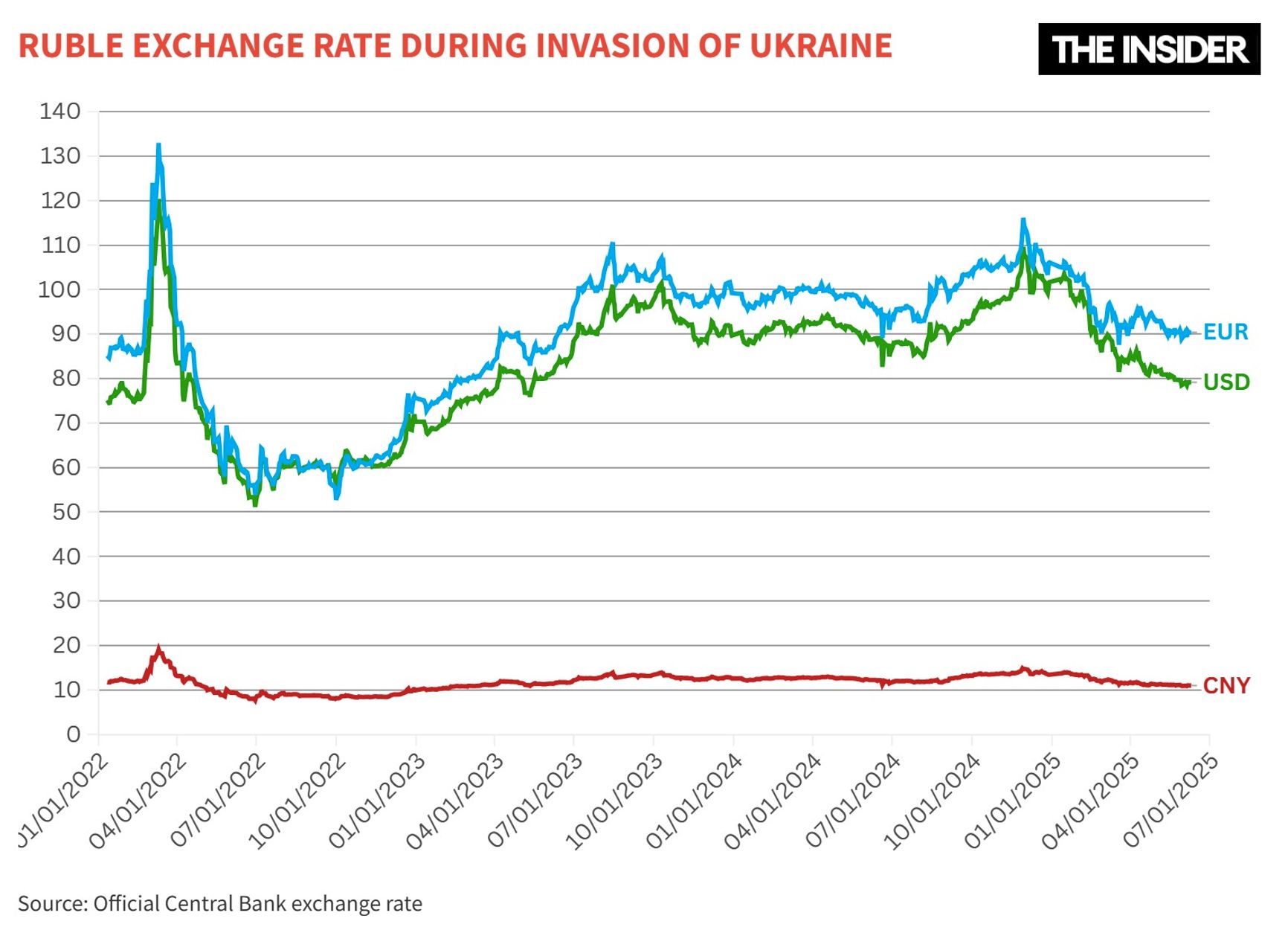

Since reaching its peak in November, the official exchange rate of the U.S. dollar in Russia has dropped 27%, the euro 21%, and the Chinese yuan 26%. The ruble continues to strengthen, despite the Central Bank of Russia’s unexpected 1 percentage point cut to its key rate — from 21% to 20%.

There are several reasons for the ruble’s appreciation. In its May analytical review, Russia’s Central Bank listed five main drivers: the high key interest rate (which makes it unprofitable to purchase imported goods on credit, but beneficial to keep money in ruble deposits); seasonality (consumer activity typically slows at the beginning of the year); optimism over a potential ceasefire (which could bring about partial sanctions relief); a “resolution” of payment system problems (alternative channels for foreign trade transactions have been found); and reduced demand for imported cars (due to the implementation of a recycling fee).

A major factor has been the physical decline in imports. In addition to sanctions, this has been influenced by falling demand — driven not only by the high interest rate and car recycling fees, but also by a slowdown in economic growth and a cooling labor market. Simply put, Russian consumers and businesses are tightening their belts. And the less imported goods are purchased, the less demand there is for foreign currency.

The high interest rate has had multiple effects. “I believe that the 21% plus interest on commercial loans has become prohibitively expensive for some large companies,” economist Oleg Vyugin told The Insider. In response to sanctions that have affected the Russian currency market, the government allowed exporting companies to keep a greater share of their foreign currency earnings abroad. As a result, many have accumulated substantial reserves.

“When loans were more accessible, exporters preferred borrowing to replenish working capital rather than selling foreign currency revenues. Now, with higher borrowing costs, I believe they’ve started to repatriate currency to Russia and sell it to cover those needs,” Vyugin explained.

Another factor is the so-called carry trade. “Players borrow money at low euro interest rates, convert it into rubles, and then purchase government bonds or simply place the funds in ruble bank deposits, earning substantial interest on one-month accounts. If their bank is located in a friendly country, all transactions go through it without the funds ever physically entering Russia. They still earn their 19%, which is a very good rate when you’re borrowing at 2-3% in the eurozone,” economist Sergey Aleksashenko told The Insider.

Who benefits?

The ruble’s appreciation brings clear advantages to consumers and businesses reliant on imported components. This is particularly significant considering that imported food accounts for 20-25% of the average Russian consumer basket, and the share of imported non-food goods reaches an impressive 40%.

A strong ruble means that every imported product becomes noticeably cheaper (at least for the importing company), easing inflationary pressure and slowing so-called imported inflation — the rise in prices of goods brought into the country.

“High interest rates have become one of the key drivers of the ruble’s appreciation. Combined with weakening demand, this has had a noticeable impact on price trends in the non-food sector. As a result, many household appliances and electronics — such as smartphones, televisions, and vacuum cleaners — have seen little to no increase in price, and in some cases have even become cheaper over the past year,” said Central Bank Governor Elvira Nabiullina.

The strengthening of the ruble was influenced by the high interest rate, as well as a slowing economy and reduced demand for imports.

There has also been a sharp surge in demand for international travel. In February and March, the booking aggregator Yandex Travel recorded a monthly spike of 20%, with year-over-year growth exceeding 40%. Tourists are actively booking trips not just for the immediate future, but also for autumn and winter.

The effect has been particularly strong in Asian markets. According to data from SberIndex and OneTwoTrip, international routes accounted for 26.1% of total airline ticket sales in the first quarter — an increase of nearly 5 percentage points year-on-year.

Travel platforms such as Aviasales and Yandex Travel are reporting significant growth, while tour operators including Anex, Fun & Sun, and Russian Express have noted a marked uptick in interest in international destinations. According to Sletat.ru, first-quarter foreign tour bookings rose 24.2% year-on-year..

Finally, the ruble’s strength reduces overall price pressure, theoretically giving the Central Bank more room to maneuver. If the ruble’s appreciation leads to a sustained slowdown in inflation, conditions would be ripe for a looser monetary policy and potentially multiple cuts in the key interest rate — not just a one-off.

This could breathe new life into economic activity. As shown by the government-affiliated Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short-Term Forecasting (CMASF), the civilian industrial sector has already entered a recession, buckling under the weight of high rates for borrowing. Shortly before the Central Bank’s recent meeting, Economic Development Minister Maxim Reshetnikov even warned of a possible “overcooling” (read: “crisis”) of the economy if the Bank does not begin cutting rates.

The cost of a strong ruble

The main challenge presented by the strong ruble is the strain it places on Russia’s federal budget. Coupled with falling oil prices, the result is a toxic mix: in May, oil and gas revenues were down by a third compared to the same month last year, and they dropped 53% relative to April. Overall, since the beginning of the year, oil and gas revenues are down 14% year over year. This is a growing concern for the Finance Ministry — especially given that the budget deficit also increased notably in the spring, reaching 1.5% of GDP.

The mechanics are simple: the ruble price of Russian oil fell to 4,195 per barrel in May. That’s the lowest level since April 2023. As a result, the government has been forced to dip into the National Wealth Fund (NWF), which now holds less than 3 trillion rubles ($38 billion).

Those benefiting from the strong ruble are Russian consumers; those losing out are exporters — and the state budget.

A strong ruble makes Russian products less attractive on the global market, and wheat serves as a prime example. At the start of 2025, Russian wheat exports dropped to their lowest level in eight years. Due to the ruble’s appreciation and low purchase prices, exporting wheat simply became unprofitable. Its competitiveness in global markets declined, and Russian wheat became more expensive than its European counterpart. Against this backdrop, the Ministry of Agriculture is preparing to amend the grain export quota distribution mechanism.

Forecasts for the future

The prolonged ruble rally is widely considered unstable, primarily due to budgetary constraints. The ruble traditionally weakens in the summer, when vacationers take advantage of cheaper travel packages and importers gear up for the New Year’s retail season by increasing purchases of foreign goods.

The Central Bank’s interest rate cut was modest, but it could still provide a positive signal to the economy. “Even a symbolic reduction of 100 basis points, bringing the rate down to 20%, is important because it marks a return to the trajectory of normal economic functioning,” commented Alexander Shokhin, head of the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs (RSPP) in the run-up to the Central Bank’s decision. In this scenario, economic revival could prompt companies to ramp up imports, increasing demand for foreign currency — and further rate cuts are possible.

As happens every year, July will see a regulated rise in the cost of utilities — and in the current environment, these hikes play a growing role in stoking inflation. Utility and electricity rates are set to increase by 12%. Gazprom, having lost the European market and still failing to fully compensate via Asian customers, lobbied for a nearly 12% increase in domestic gas prices. At the same time, the real interest rate — the gap between the Central Bank’s key rate and inflation — remains extraordinarily high. Even under tight monetary policy, this gap rarely exceeds 5-6%, while 2% is considered normal. In other words, the Central Bank has substantial room to lower rates.

“The carry trade is a factor completely unrelated to the real state of the Russian economy — it’s a reaction to high interest rates,” economist Aleksashenko told The Insider. “So if the Central Bank begins to truly believe that inflation is slowing, the flow of capital into rubles due to the interest rate differential will reverse and start to leave. It’s not a matter of if that will happen, but when.”

Sanctions, including those imposed on the Moscow Exchange, have made the currency market thin and volatile — yet another factor working against ruble stability. “There is virtually no foreign capital flowing into the Russian currency market compared to pre-war levels. Russia is effectively isolated from foreign investment. All inflows are domestic, and they’re limited,” commented Alexander Kolyandr, a senior fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA). “As a result, the market is what you’d call shallow, so even a small disruption now causes a much greater impact than it would have before 2022. With the ruble left to float freely, its exchange rate will swing up and down, and high volatility is inevitable for that very reason.”

Another key variable is how the ruble would behave if a ceasefire between Russia and Ukraine is reached. Expectations are for no agreement before autumn, following the summer military campaign. However, U.S. President Donald Trump’s leadership is not known for its predictability. While he may be suggesting at the moment that Russia and Ukraine can “fight for a while” longer, he could also just as quickly decide that enough is enough.

It is likely that the ruble would initially strengthen on the mere announcement of a ceasefire. But what comes next could be a sharp decline. “If the war ends, I would expect a swift monetary loosening and an immediate devaluation of about 20–35%. There will be a need to reallocate labor from the military sector. Inflationary pressures will likely remain elevated for another one to two years, even with a fast end to the war,” said Dmitry Nekrasov, director of the Center for Analysis and Strategies in Europe (CASE).

Much will depend on whether sanctions are lifted — and which ones. If imports and capital outflows resume quickly, the ruble could weaken further due to higher foreign currency demand. A situational shortage of hard currency is even possible in the immediate aftermath of a ceasefire. However, the ruble might then regain strength as the economy breathes easier, consumer confidence rebounds, and foreign investors return to the market.

What should Russians do with their rubles?

This complex set of unknowns is understandably confusing for ordinary citizens, who are unsure what to do with their money. Should they put it in a deposit while interest rates remain high? Convert to dollars while they’re still cheap (and before deposits are frozen, as some rumors suggest they will be)? Or perhaps buy gold?

If the savings are modest and may be needed soon — for a vacation or a large planned purchase — it makes sense to keep the money in a ruble deposit. The highest rates are generally offered on deposits with a term of 6–8 months. Yes, banks, acting on insider knowledge, began cutting rates a few days before the Central Bank’s move. But the cuts have so far been limited: according to a report by the business publication RBC, the average rate among the top 10 banks is 19.36% for three-month deposits, 19.4% for six-month deposits, and 18.81% for one-year terms. Even if rates continue to fall, short-term deposits should still outpace inflation for a while.

Longer-term savings — such as for a down payment on a home — are a different matter. Government bonds (OFZs), which can run up to 10 years, are often recommended. But investors must factor in taxes on coupon income and acknowledge that this is direct funding of the Russian budget — which, ultimately, means funding the war.

Short-term deposits are still the best bet for safeguarding one’s rubles from inflation.

For very long-term goals — like retirement savings or a college fund for a child not yet in preschool — switching to dollars may be more prudent. In the long run, the ruble has always depreciated; this has been true since the currency was liberalized in 1992.

Traditionally, the most promising strategy is to invest at least part of one’s savings in equities. Stock prices often rise when the ruble weakens, and value grows alongside business development. Moreover, the Russian market is severely undervalued — comparable Western companies trade at significantly higher multiples.

Over the long haul, a well-diversified stock portfolio can yield much better returns than ruble deposits or dollar hoarding. The problem is not just that most Russian citizens lack investment skills and access to the stock market — it’s also the ongoing carve-up of businesses across the country. When a profitable company is suddenly seized by prosecutors and handed over to politically connected individuals, forecasting its future — or even survival — becomes difficult.

To some extent, these risks are mitigated by Russian equivalents of ETFs, but there are few of them, fees are relatively high, and a strong performance track record has yet to be established. So the options are either to consult a trusted financial advisor — if the investment amount is substantial — or to proceed at your own risk by buying blue chips, that is, shares of the largest companies, while trying to diversify investments across as many economic sectors as possible.

Despite its recent price surge, gold is arguably the least profitable investment available at the moment. Transaction costs are high for any gold-related product — from physical bars to metal accounts. Plus, gold is a fear-driven investment. As soon as hope returns to the markets, gold prices typically fall.

The only real rationale for investing in gold is to hold it as a “rainy day” reserve. You don’t know when that day will come, what the ruble will be worth, or whether foreign currency will even be legal to own. Yes, in a worst-case scenario, a gold bar might buy you a loaf of bread — but that’s the whole point: to have something to buy that bread with. If you’re still drawn to gold, treat it like an insurance policy — expensive, likely unnecessary, but irreplaceable when you need it most.