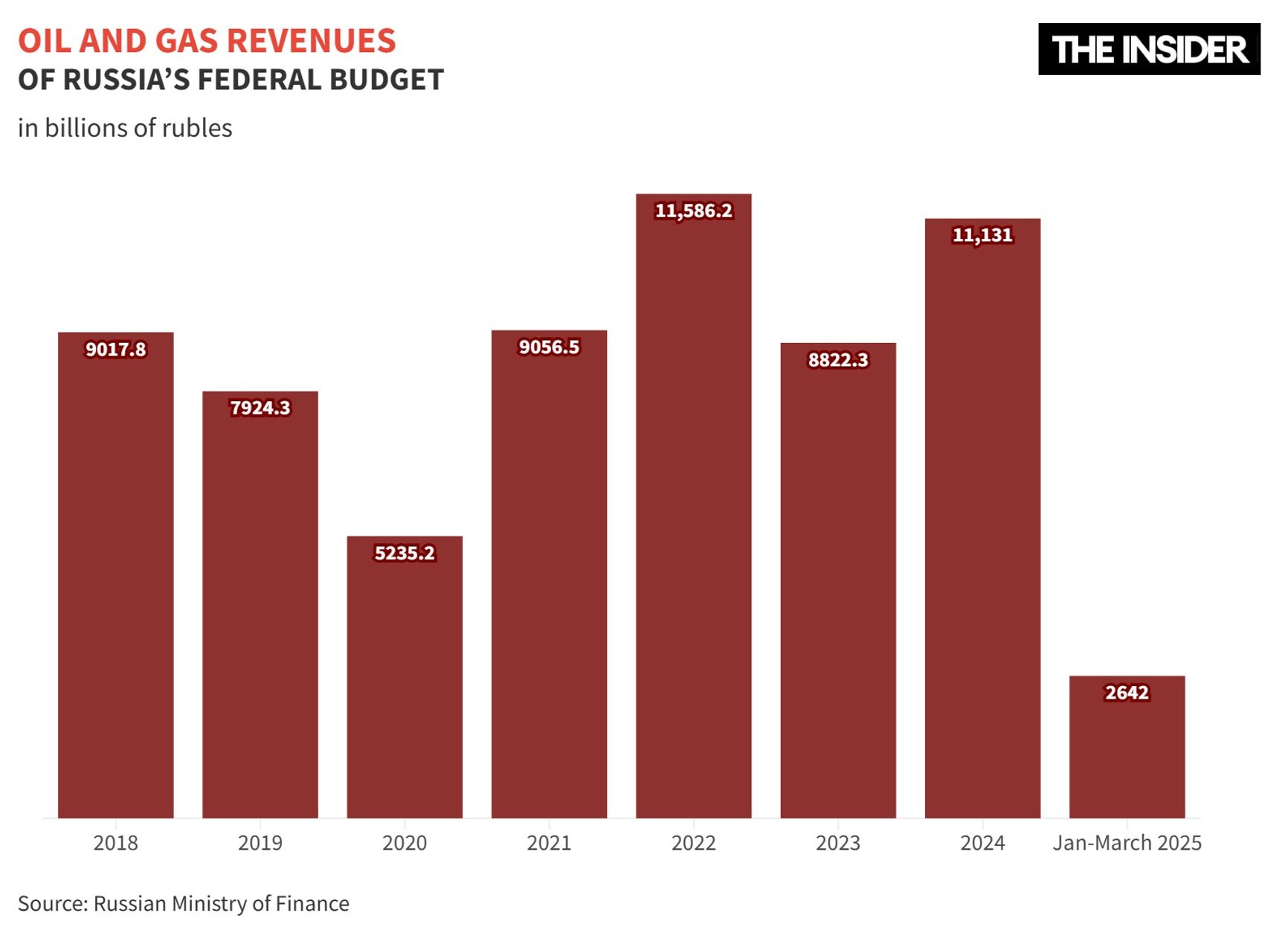

Russia’s oil and gas revenues have already fallen by 10% — and that may be just the beginning. Oil prices are sliding amid fears of a global economic slowdown triggered by the US-China tariff war, along with rising production from OPEC+ countries. Goldman Sachs warns that in a worst-case scenario, oil could plunge to $40 a barrel by 2026. Even the bank’s more moderate forecast isn’t much better: $55 a barrel. For Russia, that could mean: at best; another round of inflation and ruble devaluation; and at worst, a banking crisis and industrial shock.

Content

Oil trapped in a perfect storm

Why OPEC is increasing production

Russia can produce a lot, but not for long

The oil needle and the 'black swan'

Chronicle of a possible collapse

Oil trapped in a perfect storm

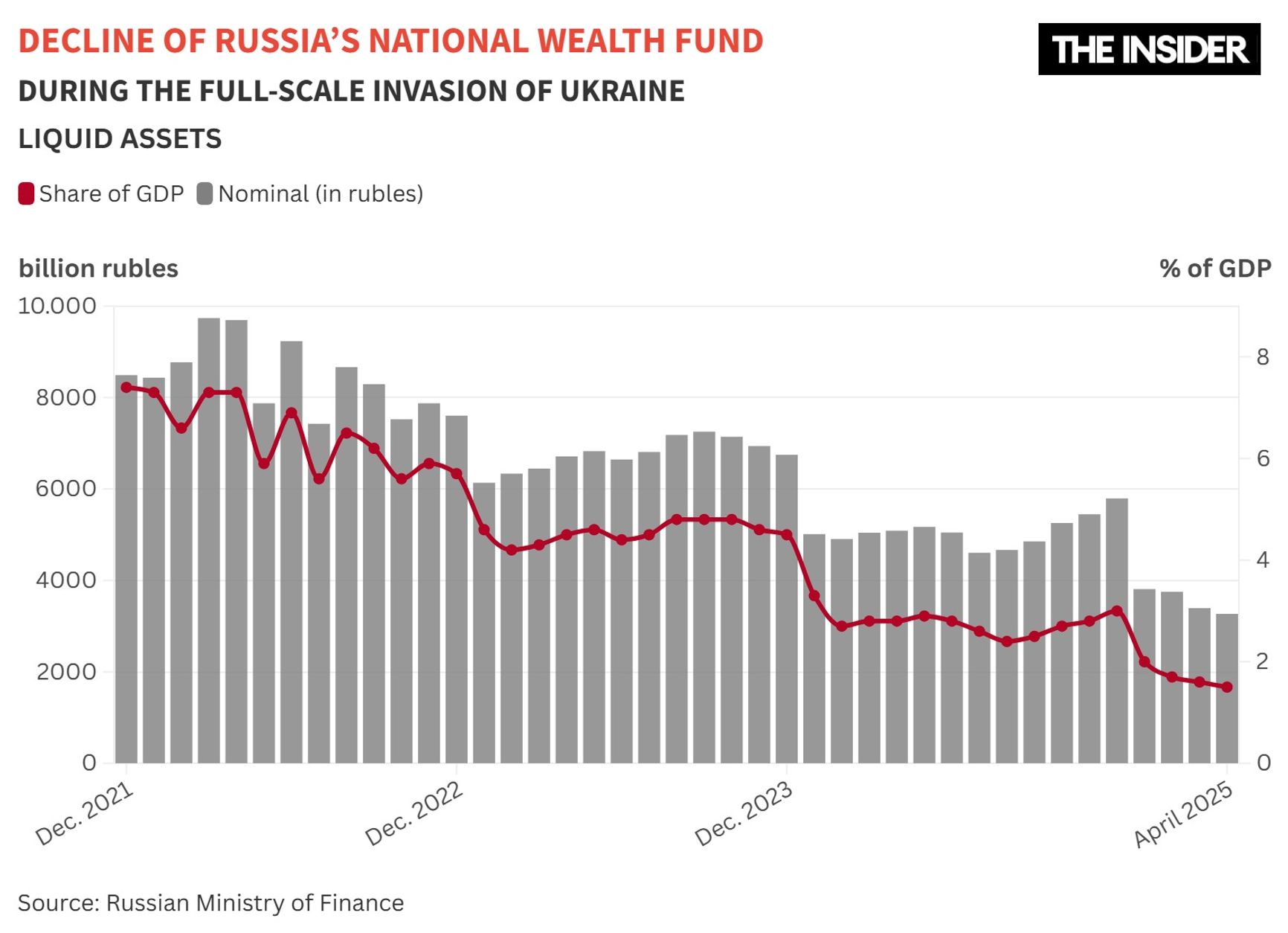

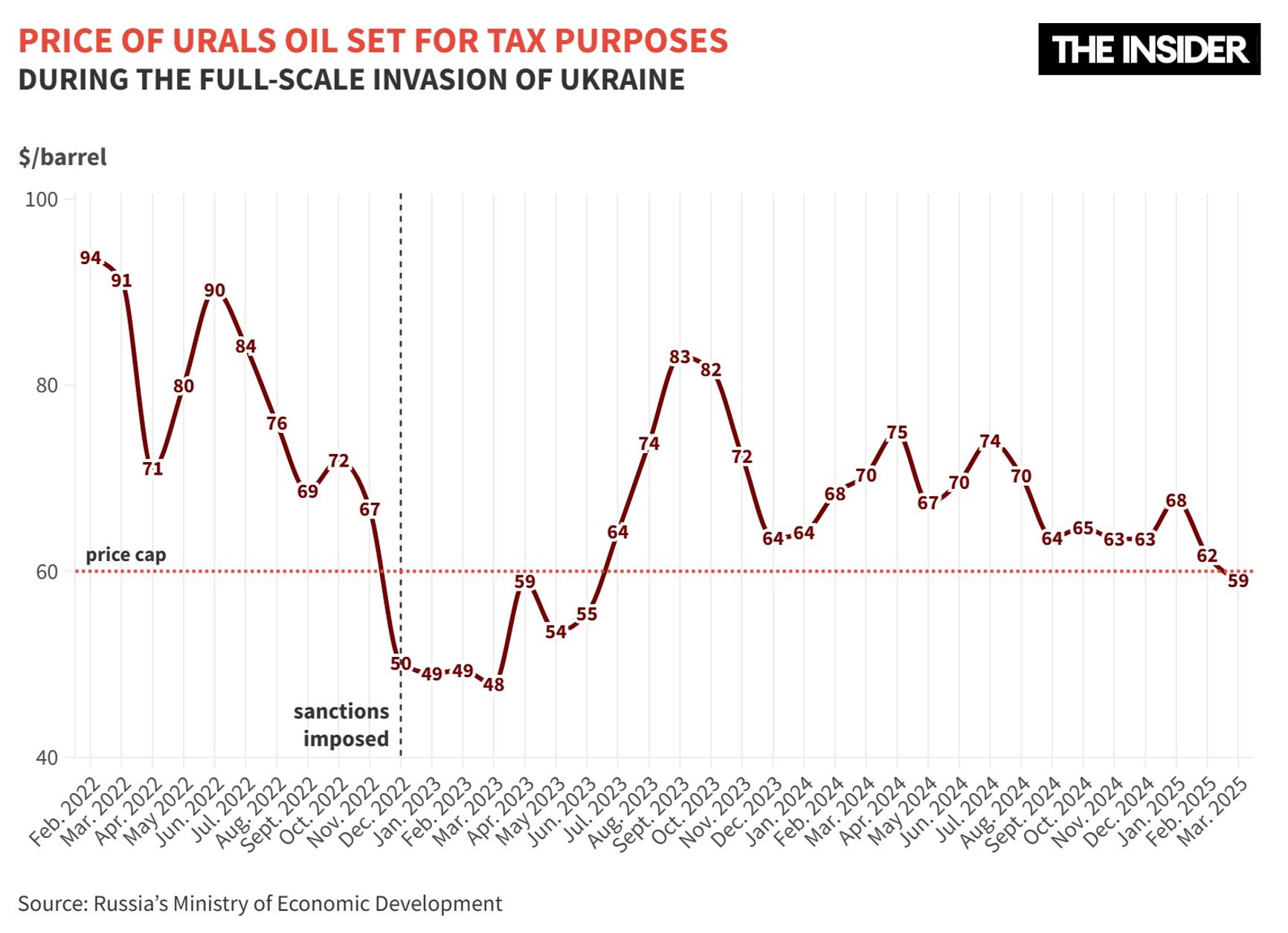

Russia’s budget is based on oil selling at $70 a barrel, but the market price is well below that. As a result, oil and gas revenues in the first quarter dropped 10% compared to the same period last year. Moscow’s Finance Ministry now expects the average price for the year to hover around $60 for Urals crude — which means the National Wealth Fund (NWF) won’t be replenished, and the budget deficit is likely to grow. In April, after U.S. President Donald Trump launched a new round of tariff measures, the price of Urals crude dipped below $50 a barrel. This year, the Finance Ministry has already had to sell foreign currency from the NWF to make up for lost oil revenue.

Analysts believe oil prices could remain low for quite some time. Goldman Sachs’ extreme-case scenario — factoring in slower global GDP growth and a rise in OPEC+ production — sees Brent crude falling to just under $40 a barrel by the end of 2026. The bank considers this outcome unlikely, but its base forecast still puts Brent at $55 a barrel. That would translate to around $40 for Urals, since the price gap tends to widen as oil prices fall and narrow when they rise.

Even OPEC has lowered its forecast for global oil demand growth in 2025. “This slight downward revision mainly reflects recent first-quarter data and the expected impact of the newly announced U.S. tariffs on oil demand,” the organization said in its latest report.

Partly due to the large one-time receipts from additional oil extraction tax (NDPI) payments in February 2024, but also due to a decrease in the average oil price, according to the Ministry of Finance.

An unofficial format created in November 2016. In addition to core OPEC members, it includes 11 countries: Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Brunei, Brazil, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Mexico, Oman, Russia, Sudan, South Sudan.

Demand is expected to grow by 1.3 million barrels per day, rather than 1.4 million as previously estimated, totaling 106.33 million barrels per day.

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, or OPEC, was founded in September 1960 and currently includes Algeria, Venezuela, Gabon, Iraq, Iran, Congo, Kuwait, Libya, UAE, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, and Equatorial Guinea. OPEC countries control two-thirds of the world's oil reserves, account for 35% of global production and half of exports.

A gas lift is a type of pump that pushes oil to the surface together with water by injecting compressed gas into the wells.

Of course, oil prices could instead spike if the U.S. strikes Iran — provided that global traders see a threat to shipping routes. However, during previous Middle East crises — whether the war between Israel and Hamas or the Houthi missile attacks on tankers sailing past Yemen — each price surge has been smaller than the last, reinforcing the downward trend.

That trend is driven not only by expectations of falling demand — due to the global shift towards alternative energy sources and electric vehicles, along with fears of recession — but also by growing supply. In March, the OPEC+ countries recorded their highest output in eight months: more than 41 million barrels a day, according to Platts. At the same time, the biggest producers — Russia and Saudi Arabia — are still producing less than they could, having yet to fully use their quotas.

In early April, the oil market was hit by a perfect storm, Carnegie Center Berlin senior fellow Sergey Vakulenko explained in an interview with The Insider. After Trump’s announcement of a “day of liberation” and the start of the tariff war, global stock markets began to tumble, dragging oil prices down with them. Futures contracts for oil are a market-traded asset, Vakulenko explains, meaning that when the markets fall, oil prices fall too. On top of that, Trump’s tariffs heightened expectations of a recession — JPMorgan estimated the probability at 79% — which further pushed down oil prices given that a recession implies lower demand.

Adding fuel to the fire was the April OPEC+ meeting, where a decision was made to increase production. “Not only is OPEC+ starting to lift its quotas — despite earlier hopes the alliance would hold firm on its promise — but the first wave of this rollback is more aggressive than expected: not an increase of 138,000 barrels a day, but 411,000. While that’s still not much compared to the 105 million barrels a day consumed globally, it’s not nothing — that’s a 0.5% boost instead of 0.15%. And reportedly, this decision was pushed through by Saudi Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman — the same man who crashed oil prices five years ago,” Vakulenko says.

Why OPEC is increasing production

Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman is a “very tough player,” Vakulenko notes. His philosophy is to “kick the one who’s already falling,” and he has little tolerance for “cheaters who exceed their oil production limits — he doesn’t like bailing out those who ride the price coattails of OPEC.” That’s why, from time to time, he drives prices down — and he does it at precisely the most effective moments, when prices are already heading for a drop.

Five years ago, in early March 2020, Russia refused to accept new production cuts, and in response, Saudi Arabia announced it was lifting all restrictions on its own production. Oil prices crashed by 30% in a single day — the steepest drop since 1991. Russia quickly came around and has since behaved more or less within the rules — exceeding its production quota, but only slightly. It’s worth noting that Russia’s defiance in 2020 was not the product of stubbornness: unlike many other countries, Russia has difficulty ramping production back up once it’s been sharply reduced.

Partly due to the large one-time receipts from additional oil extraction tax (NDPI) payments in February 2024, but also due to a decrease in the average oil price, according to the Ministry of Finance.

An unofficial format created in November 2016. In addition to core OPEC members, it includes 11 countries: Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Brunei, Brazil, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Mexico, Oman, Russia, Sudan, South Sudan.

Demand is expected to grow by 1.3 million barrels per day, rather than 1.4 million as previously estimated, totaling 106.33 million barrels per day.

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, or OPEC, was founded in September 1960 and currently includes Algeria, Venezuela, Gabon, Iraq, Iran, Congo, Kuwait, Libya, UAE, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, and Equatorial Guinea. OPEC countries control two-thirds of the world's oil reserves, account for 35% of global production and half of exports.

A gas lift is a type of pump that pushes oil to the surface together with water by injecting compressed gas into the wells.

Russia, unlike many other countries, finds it difficult to ramp production back up once it’s been sharply reduced

Oil fields can be roughly divided into two categories: land-based and offshore (shelf) fields. On land, oil is extracted either through free flow or with the help of gas lifts. Free-flowing land-based wells provide for the simplest and cheapest extraction. Offshore fields are more expensive, and those in polar regions even more so. And the most expensive methods are horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing.

In the Persian Gulf countries, oil is mostly free-flowing. In Latin America (Brazil, Guyana) and Norway, it’s produced offshore. In the U.S., oil is extracted both offshore in the Gulf of Mexico and onshore in the Permian Basin, where production relies on shale extraction through hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling. In Russia, offshore fields are located in polar latitudes, and on land, most fields are old and require horizontal drilling.

Partly due to the large one-time receipts from additional oil extraction tax (NDPI) payments in February 2024, but also due to a decrease in the average oil price, according to the Ministry of Finance.

An unofficial format created in November 2016. In addition to core OPEC members, it includes 11 countries: Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Brunei, Brazil, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Mexico, Oman, Russia, Sudan, South Sudan.

Demand is expected to grow by 1.3 million barrels per day, rather than 1.4 million as previously estimated, totaling 106.33 million barrels per day.

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, or OPEC, was founded in September 1960 and currently includes Algeria, Venezuela, Gabon, Iraq, Iran, Congo, Kuwait, Libya, UAE, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, and Equatorial Guinea. OPEC countries control two-thirds of the world's oil reserves, account for 35% of global production and half of exports.

A gas lift is a type of pump that pushes oil to the surface together with water by injecting compressed gas into the wells.

Development of the Prirazlomnoye oil field (Russia)

Photo: Max Avdeev

Horizontal drilling requires precise calculations — where exactly to branch out from the vertical well, at what angle, and so on. Because Russia's older fields are so depleted, restarting such a well is difficult: the oil may have shifted to different layers through underground fissures, or the well may fill with water. Sanctions have made things even more complicated, as developing offshore fields in polar regions like the Kara and Okhotsk seas, as well as carrying out horizontal drilling, requires advanced technologies.

Russia has routinely exceeded its OPEC+ quotas in part because the bonuses of oil company executives are tied to profitability, not to compliance with OPEC agreements. These breaches were mostly not egregious — “like a mischievous kid testing how much they can get away with before they’re punished,” says Vakulenko.

Partly due to the large one-time receipts from additional oil extraction tax (NDPI) payments in February 2024, but also due to a decrease in the average oil price, according to the Ministry of Finance.

An unofficial format created in November 2016. In addition to core OPEC members, it includes 11 countries: Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Brunei, Brazil, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Mexico, Oman, Russia, Sudan, South Sudan.

Demand is expected to grow by 1.3 million barrels per day, rather than 1.4 million as previously estimated, totaling 106.33 million barrels per day.

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, or OPEC, was founded in September 1960 and currently includes Algeria, Venezuela, Gabon, Iraq, Iran, Congo, Kuwait, Libya, UAE, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, and Equatorial Guinea. OPEC countries control two-thirds of the world's oil reserves, account for 35% of global production and half of exports.

A gas lift is a type of pump that pushes oil to the surface together with water by injecting compressed gas into the wells.

Russia routinely exceeded OPEC+ quotas, but stayed just shy of getting penalized

What really angered Prince Abdulaziz was the behavior of three other countries — Iraq, Kazakhstan, and the United Arab Emirates — which have long exceeded their quotas by significant amounts. In addition, Saudi Arabia fears losing market share to players like the U.S., Brazil, and Guyana. That’s why the Saudis are ready to switch to plan B: increase production and use falling prices to squeeze out competitors with higher production costs.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), in February spare oil production capacity in the Middle East reached 4.8 million barrels a day. For comparison, Iraq — OPEC’s second-largest producer — was pumping 4.2 million barrels a day that same month.

In the Persian Gulf countries, the average production cost — which includes not only extraction, but also construction, transportation, and maintenance — is around $10–15 per barrel. For U.S. shale fields and Latin America’s offshore projects, the cost is $40–45. According to Vakulenko, that’s also roughly what it costs Russia to extract oil at new sites. Older fields are cheaper — around $25 — which is why there’s a strong incentive to keep them operational.

Russia can produce a lot, but not for long

Can Russia ramp up oil production? According to the EIA, as of February 2025 Russia’s oil output — excluding gas condensate and light hydrocarbons — stood at 8.93 million barrels per day, 11% below its February 2022 level of 10.05 million bpd. The drop was tied to the OPEC+ agreement, which had capped Russia’s quota at 8.98 million bpd through March 2025. At present, Russia is allowed to increase production to 9.083 million bpd.

“There’s still some spare capacity,” says Vakulenko. But if Russia ramps up output now, the decline will be even sharper in a few years. Production at older fields is already falling, and the development of new fields became more difficult after the war began, as sanctions cut the sector off from modern technology and foreign investment. On top of that, the government is aggressively pulling revenue from exporters into the federal budget.

Partly due to the large one-time receipts from additional oil extraction tax (NDPI) payments in February 2024, but also due to a decrease in the average oil price, according to the Ministry of Finance.

An unofficial format created in November 2016. In addition to core OPEC members, it includes 11 countries: Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Brunei, Brazil, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Mexico, Oman, Russia, Sudan, South Sudan.

Demand is expected to grow by 1.3 million barrels per day, rather than 1.4 million as previously estimated, totaling 106.33 million barrels per day.

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, or OPEC, was founded in September 1960 and currently includes Algeria, Venezuela, Gabon, Iraq, Iran, Congo, Kuwait, Libya, UAE, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, and Equatorial Guinea. OPEC countries control two-thirds of the world's oil reserves, account for 35% of global production and half of exports.

A gas lift is a type of pump that pushes oil to the surface together with water by injecting compressed gas into the wells.

Production at older fields is already falling, and new development became difficult after the war due to sanctions

Still, there are ways to keep older fields producing — for instance, by tightening the grid of wells. Vakulenko explains:

“If you drill a new well relatively close to an existing one, you can extract oil from the same reservoir twice as fast and also increase the recovery factor. That ‘thief well’ might steal about 70–80% of the oil that the original well would have produced five years down the line — but it also brings up 20–30% of the oil the old well would never have reached.”

But of course, by pursuing such a strategy, Russia would quickly burn through its cheapest-to-extract reserves much faster. Saudi Arabia “crashed” oil prices in 1985 and didn’t stop flooding the market until 2000, but Russia is not equipped to run such a marathon today.

One reason is sanctions. Goldman Sachs estimates that Saudi Arabia needs an oil price of at least $90 a barrel to balance its mega-project heavy state budget. However, unlike sanction-burdened Russia, the Saudis can afford to take on more government debt and attract foreign investment.

Russia’s budget is based on a lower oil price, but given that the country can no longer borrow on international markets, Moscow is more vulnerable to downward shocks. Domestic borrowing, meanwhile, is becoming less attractive, especially with record-high interest rates from the Central Bank. If prices fall, Russia may have to live out the old saying: “While the fat one is slimming down, the skinny one is already dead.”

The oil needle and the 'black swan'

Russian officials often claim that their country has “kicked the oil habit.” But that’s not true. “Whatever they say, oil revenues still play a key role in funding the federal budget,” says Ruben Enikolopov, academic director at NES and a professor at Pompeu Fabra University. “You have to look not only at the mineral extraction tax, but also at taxes paid by businesses linked to the oil sector — for example, contractors paying profit tax,” he explains.

“Russia’s entire economy is tied to oil, because any revenue from oil has a multiplier effect,” says Tatyana Mikhailova, visiting lecturer at Penn State University. When oil companies earn extra profits, they tend to reinvest it domestically, boosting economic activity: firms in other industries get contracts, their employees get paid — and everyone pays taxes, she adds. “There has been no diversification of the Russian economy. Period,” Enikolopov concludes.

Even Russian Central Bank head Elvira Nabiullina has pointed out that falling oil prices are the main channel through which global crises affect Russia’s economy. If the standoff between the U.S. and China continues, and if global tariff wars escalate, she has warned, there could be a drop in “demand for our energy resources.”

Partly due to the large one-time receipts from additional oil extraction tax (NDPI) payments in February 2024, but also due to a decrease in the average oil price, according to the Ministry of Finance.

An unofficial format created in November 2016. In addition to core OPEC members, it includes 11 countries: Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Brunei, Brazil, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Mexico, Oman, Russia, Sudan, South Sudan.

Demand is expected to grow by 1.3 million barrels per day, rather than 1.4 million as previously estimated, totaling 106.33 million barrels per day.

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, or OPEC, was founded in September 1960 and currently includes Algeria, Venezuela, Gabon, Iraq, Iran, Congo, Kuwait, Libya, UAE, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, and Equatorial Guinea. OPEC countries control two-thirds of the world's oil reserves, account for 35% of global production and half of exports.

A gas lift is a type of pump that pushes oil to the surface together with water by injecting compressed gas into the wells.

Even Elvira Nabiullina has pointed out that falling oil prices are the main channel through which global crises affect Russia’s economy

A Central Bank document titled “Main Guidelines for Monetary Policy for 2025–2027” describes a worst-case scenario for the Russian economy: a global crisis comparable to 2008–2009, in which a drop in oil prices would cause Russia’s GDP to shrink by 5%, inflation to surge to 15%, and economic normalization to take no less than two years. That’s a grim outlook, says Enikolopov — though if Trump puts his mind to it, reality could surpass even the most pessimistic forecasts.

“When Nixon dismantled the Bretton Woods system, he did it very carefully and deliberately. That kind of approach is lacking today,” Enikolopov says. Still, he believes the situation in the Russian economy is unlikely to be worse than the Central Bank’s negative scenario — unless the current crisis is compounded by another shock. “If a second ‘black swan’ emerges from a different sphere — say, a large-scale natural disaster — then a chain of diverse shocks could lead to a real catastrophe,” he explains.

Chronicle of a possible collapse

The greatest systemic crisis risks currently lie in the banking sector, according to the pro-government Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short-Term Forecasting (CMASF). These risks are still rated as moderate, but in the event of a global crisis, the transmission to Russia would follow this sequence: first a currency shock, then a liquidity freeze, followed by a credit crunch and, potentially, a simultaneous production shock.

Partly due to the large one-time receipts from additional oil extraction tax (NDPI) payments in February 2024, but also due to a decrease in the average oil price, according to the Ministry of Finance.

An unofficial format created in November 2016. In addition to core OPEC members, it includes 11 countries: Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Brunei, Brazil, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Mexico, Oman, Russia, Sudan, South Sudan.

Demand is expected to grow by 1.3 million barrels per day, rather than 1.4 million as previously estimated, totaling 106.33 million barrels per day.

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, or OPEC, was founded in September 1960 and currently includes Algeria, Venezuela, Gabon, Iraq, Iran, Congo, Kuwait, Libya, UAE, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, and Equatorial Guinea. OPEC countries control two-thirds of the world's oil reserves, account for 35% of global production and half of exports.

A gas lift is a type of pump that pushes oil to the surface together with water by injecting compressed gas into the wells.

In the event of a global crisis, Russia might first face a currency shock, then a liquidity freeze, followed by a credit crunch and, potentially, a production shock

Enikolopov agrees that under such a negative scenario, lending would be the first to suffer. “In fact, all crises ultimately evolve into financial ones. But credit risks can be managed by the state. A serious drop in oil prices, however, would simply leave the government without money — and there’s not much of it now to begin with. Plus there would be nowhere left to borrow from,” he says.

What makes the current situation worse for Russia than the crises of 2008 and 2020 is that the state’s “rainy-day fund” is nearly empty: by April, the liquid portion of the National Wealth Fund stood at 3.3 trillion rubles, or 1.5% of GDP. According to Enikolopov, if budget revenues collapse, this money would last a year at most — or up to three years under a more gradual decline. True, there are also the Central Bank’s foreign reserves, which now consist mostly of gold and yuan after half of them were frozen in the EU and U.S. But the yuan presents a challenge of its own: as China enters a trade war with the U.S., its government is devaluing the currency.

Partly due to the large one-time receipts from additional oil extraction tax (NDPI) payments in February 2024, but also due to a decrease in the average oil price, according to the Ministry of Finance.

An unofficial format created in November 2016. In addition to core OPEC members, it includes 11 countries: Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Brunei, Brazil, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Mexico, Oman, Russia, Sudan, South Sudan.

Demand is expected to grow by 1.3 million barrels per day, rather than 1.4 million as previously estimated, totaling 106.33 million barrels per day.

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, or OPEC, was founded in September 1960 and currently includes Algeria, Venezuela, Gabon, Iraq, Iran, Congo, Kuwait, Libya, UAE, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, and Equatorial Guinea. OPEC countries control two-thirds of the world's oil reserves, account for 35% of global production and half of exports.

A gas lift is a type of pump that pushes oil to the surface together with water by injecting compressed gas into the wells.

This is likely why the Central Bank prefers gold — reserves of which hit a historic high in March. But gold is difficult to sell, and dumping large quantities on the market would depress prices. Moreover, Enikolopov warns, the Central Bank’s reserves are best left alone, as they are intended to stabilize the ruble. “If those reserves are tapped, then the 10% inflation we’re seeing now will seem like nothing. It would completely destroy monetary policy, and the situation would start to resemble either Russia in the 1990s or today’s Turkey and Argentina,” he says.

The government would rather devalue the ruble than let the National Wealth Fund run dry, economist Sergei Aleksashenko told The Insider. “The Russian budget is financed in rubles,” he notes:

“To convert the oil price used for tax calculations into actual budget revenue, you have to multiply everything by the exchange rate.

Right now, the breakeven point for the budget — the oil price-to-dollar rate ratio at which the Finance Ministry receives all the oil and gas revenues projected in the budget, including unplanned windfalls — is 6,726 rubles per barrel. But at the current exchange rate, the average price used for calculating April’s taxes comes out to just 5,300 rubles per barrel,” Aleksashenko explains.

“At $60 per barrel, the dollar would need to be 94 rubles for the Finance Ministry to collect all of its revenues. That’s not too scary, and it’s clear the ministry might allow a slight devaluation,” he continues, implying that if Russian oil were to trade at $40 a barrel over the long term, the Finance Ministry would need a dollar at 140 rubles.

Partly due to the large one-time receipts from additional oil extraction tax (NDPI) payments in February 2024, but also due to a decrease in the average oil price, according to the Ministry of Finance.

An unofficial format created in November 2016. In addition to core OPEC members, it includes 11 countries: Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Brunei, Brazil, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Mexico, Oman, Russia, Sudan, South Sudan.

Demand is expected to grow by 1.3 million barrels per day, rather than 1.4 million as previously estimated, totaling 106.33 million barrels per day.

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, or OPEC, was founded in September 1960 and currently includes Algeria, Venezuela, Gabon, Iraq, Iran, Congo, Kuwait, Libya, UAE, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, and Equatorial Guinea. OPEC countries control two-thirds of the world's oil reserves, account for 35% of global production and half of exports.

A gas lift is a type of pump that pushes oil to the surface together with water by injecting compressed gas into the wells.

“That would be a major devaluation of the ruble,” the economist notes. “Talk about the National Wealth Fund running out, oil prices crashing, everything turning into a nightmare — that comes up year after year. But knowing how the Finance Ministry and Central Bank operate, I can say that if the ruble-denominated price of oil drops well below 5,600 rubles, then the Finance Ministry will definitely reach an agreement with the Central Bank on devaluation,” Aleksashenko asserts.

In response to the decline in oil revenues, the authorities may also choose to cut spending. The Russian government has its own unique methods for doing this, as Mikhaylova points out: shifting the state’s responsibilities onto businesses. “This is already happening. For example, large enterprises — whether state-owned, municipal, or private — are being forced to hire those who are going to war as mercenaries, paying them salaries from company funds,” she explains. If budget revenues continue to fall, this will likely become more common.

According to Mikhaylova, all of these measures lead to inflation, and if oil prices stay low for an extended period, Russia will face a real crisis: “It’s unlikely we’ll see empty store shelves like in the late Soviet Union, or widespread wage non-payments like in the early '90s. Since the government prints money and the macroeconomic team is fairly pragmatic, we’re more likely to follow in the footsteps of Argentina and Turkey — maintaining a market economy, but one that’s growing increasingly poorer.”

Partly due to the large one-time receipts from additional oil extraction tax (NDPI) payments in February 2024, but also due to a decrease in the average oil price, according to the Ministry of Finance.

An unofficial format created in November 2016. In addition to core OPEC members, it includes 11 countries: Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Brunei, Brazil, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Mexico, Oman, Russia, Sudan, South Sudan.

Demand is expected to grow by 1.3 million barrels per day, rather than 1.4 million as previously estimated, totaling 106.33 million barrels per day.

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, or OPEC, was founded in September 1960 and currently includes Algeria, Venezuela, Gabon, Iraq, Iran, Congo, Kuwait, Libya, UAE, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, and Equatorial Guinea. OPEC countries control two-thirds of the world's oil reserves, account for 35% of global production and half of exports.

A gas lift is a type of pump that pushes oil to the surface together with water by injecting compressed gas into the wells.