Elon Musk has called to “Make Europe Great Again,” tweaking Donald Trump’s campaign slogan. Putting his money where his mouth is, the world’s richest entrepreneur has spoken at the congress of the far-right Alternative for Germany party, expressed support for British extremist Tommy Robinson, and shown support for the Italian far-right. The rightward shift, which the new U.S. administration has already begun implementing at home, entails, among other things, scaling back government spending aimed at promoting equality, cutting social programs, and reducing overall public expenditures. In this regard, the U.S. has long been significantly to the right of Europe in everything from education and healthcare to transportation and public safety. And despite the political rise of the far right, Europeans don’t seem ready to abandon these differences.

Content

How Europe isn’t America

Divided by inequality

The sweatshop system

Europeans answer to Elon Musk

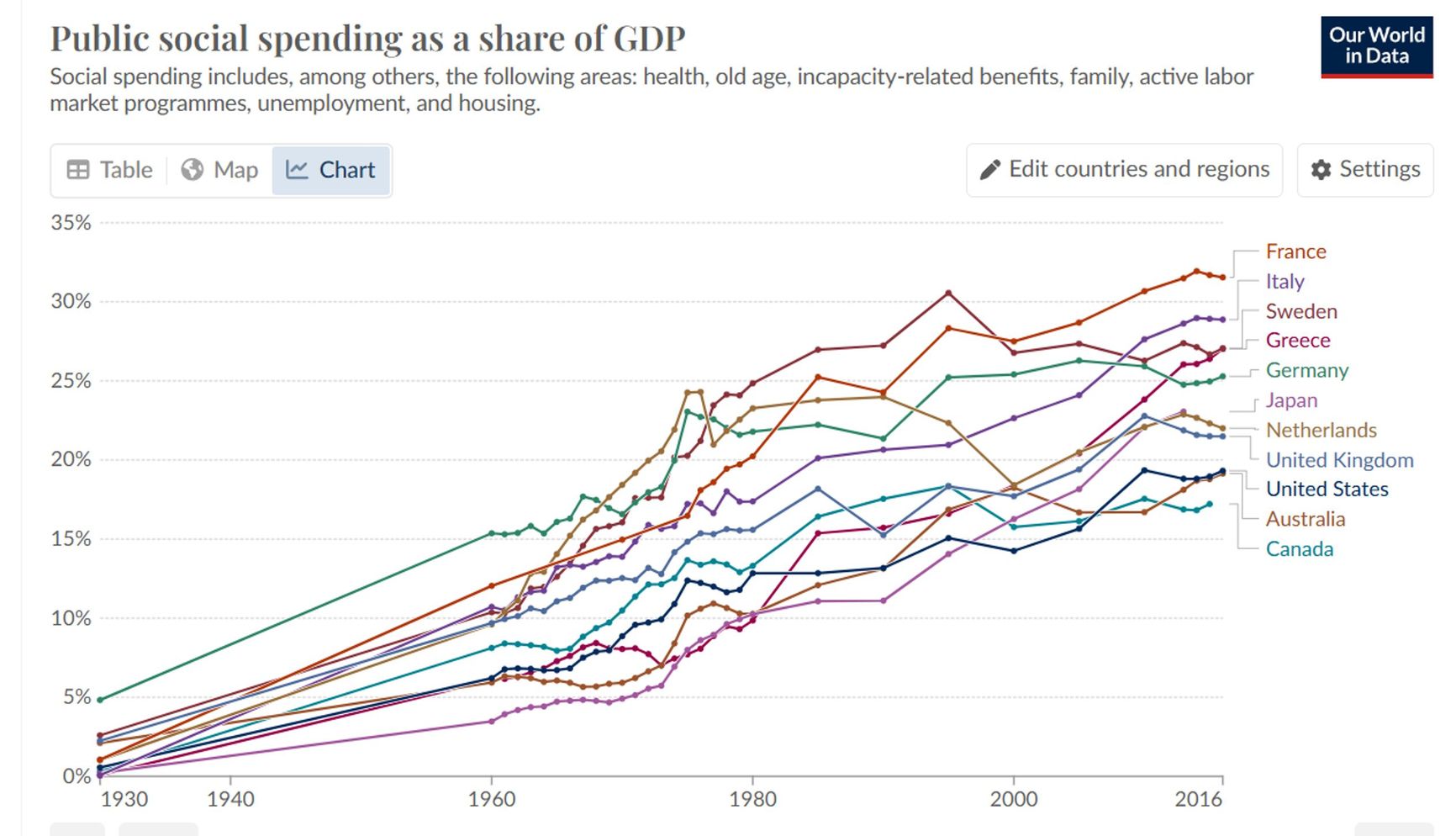

The socioeconomic systems of Europe and the U.S. began to diverge after World War II. War-torn European countries rebuilt themselves through government spending, which for the next five decades continued rising relative to GDP. In the U.S., public spending also grew rapidly in the post-war years, but social welfare programs there proved more difficult to implement. One of the few successful administrations in this regard was that of Lyndon Johnson, who in 1965 introduced health insurance for low-income people and retirees while also reforming education. However, a much larger share of the budget was spent on the Vietnam War, and gaps in the social welfare sector began to be filled by private companies. For instance, healthcare in the U.S. became a business, driving up costs. Today, 31% of all healthcare spending goes toward profits and bureaucracy rather than treatment. This is why formal indicators, such as the share of GDP allocated to public spending, can be misleading — high expenditures often end up as part of private companies’ excess profits, while those companies themselves are incentivized to minimize costs.

It was no surprise, then, that in December 2024, when Luigi Maggione shot and killed Brian Thompson, a top executive at the health insurance giant UnitedHealth Group, the murderer became a kind of folk hero among Americans. Not everyone could muster sympathy for the executive who had devised a way to use artificial intelligence to automatically identify reasons for denying coverage to patients — reportedly increasing the rejection rate ninefold over the past three years.

How Europe isn’t America

Transportation

One of the clearest examples of how government institutions function is public transportation. In the U.S., networks are well-developed primarily in large cities like New York and San Francisco, where extensive subway and bus systems exist. However, in most medium and small cities, public transit is either nonexistent or consists of a limited number of routes with long wait times. Urban planning prioritizes the convenience of drivers rather than optimizing public transportation options. In the EU, the situation is the opposite. For years, officials have worked to reduce the population’s reliance on personal cars, encouraging walking, cycling, and public transit. As a result, 10–20% of Europeans use public transportation for commuting, compared to just 2% in the U.S. This is not only a matter of convenience but also of environmental and economic impact, as Europeans spend significantly less on transportation than Americans do. The difference is particularly noticeable for lower-income individuals. According to EU data from 2023, European households spend an average of 11% of their income on transportation costs — about 5% less than their American counterparts.

This issue extends beyond municipal transit to the country’s overall transportation infrastructure. For instance, the intercity rail network in the U.S. is poorly developed, and true high-speed trains (those averaging 250 km/h or more) do not exist. The only relatively fast train, the Acela, covers the 328 km between New York and Washington in three hours, whereas Eurostar travels the 500 km between London and Paris in just over two hours — at nearly the same ticket price.

Education

Today, education in the EU is either significantly cheaper than in the U.S. or entirely free, as governments actively subsidize tuition costs. In the U.S., however, college education often imposes a heavy financial burden on students, with annual tuition fees exceeding $40,000 in some cases. The total student loan debt in the U.S. has surpassed $1.7 trillion — eight times the entire national debt of Norway. For a significant portion of the population, higher education is simply out of reach, a fact that hampers social mobility and creates poverty traps: people born into low-income families find it much harder to escape poverty.

Moreover, in the U.S., school funding is tied to students’ performance on standardized tests. Schools in affluent communities often receive high ratings and the largest share of funding, while schools in rural and low-income areas tend to receive lower ratings, as students there frequently face external stressors and responsibilities outside of school that negatively impact their academic performance. This reinforces the poverty trap: if you are born into a poor family in a struggling neighborhood, you are likely to attend an underfunded school with limited resources.

All of this creates a vicious cycle of low educational attainment — especially for rural populations and urban communities historically affected by racial discrimination. Many people see little value in education and rarely aspire to attend college or university, considering the exorbitant costs to be an unreasonable investment.

As a result, overall literacy levels in the U.S. are declining. In 2024, 21% of American adults were classified as “functionally illiterate” (possessing only the most basic reading and writing skills), while 54% had literacy levels below a sixth-grade standard.

21% of American adults are illiterate, while 54% have literacy levels below a sixth-grade standard.

For comparison, in Germany the functionally illiterate population is around 6–7%, in France it is about 10%, in the UK it is 16% — though in Russia, it is a comparable 22–25%. Low literacy levels impact workforce qualifications and labor productivity, significantly affecting economic performance.

Healthсare

The lack of access to medical services is another acute issue in the U.S., whereas European countries have universal health insurance, and private medical expenses are sometimes reimbursed. In Germany, out-of-pocket medical costs are capped at a fixed percentage of income: 2% of gross income for all patients and 1% for those with chronic illnesses. Any expenses exceeding these thresholds are fully covered by the state.

More than 40% of Americans are in medical debt.

Low literacy also plays a role here: Americans lose more than $230 billion annually due to unnecessary healthcare expenses, as nearly half of the population lacks the reading skills necessary to understand medical information.

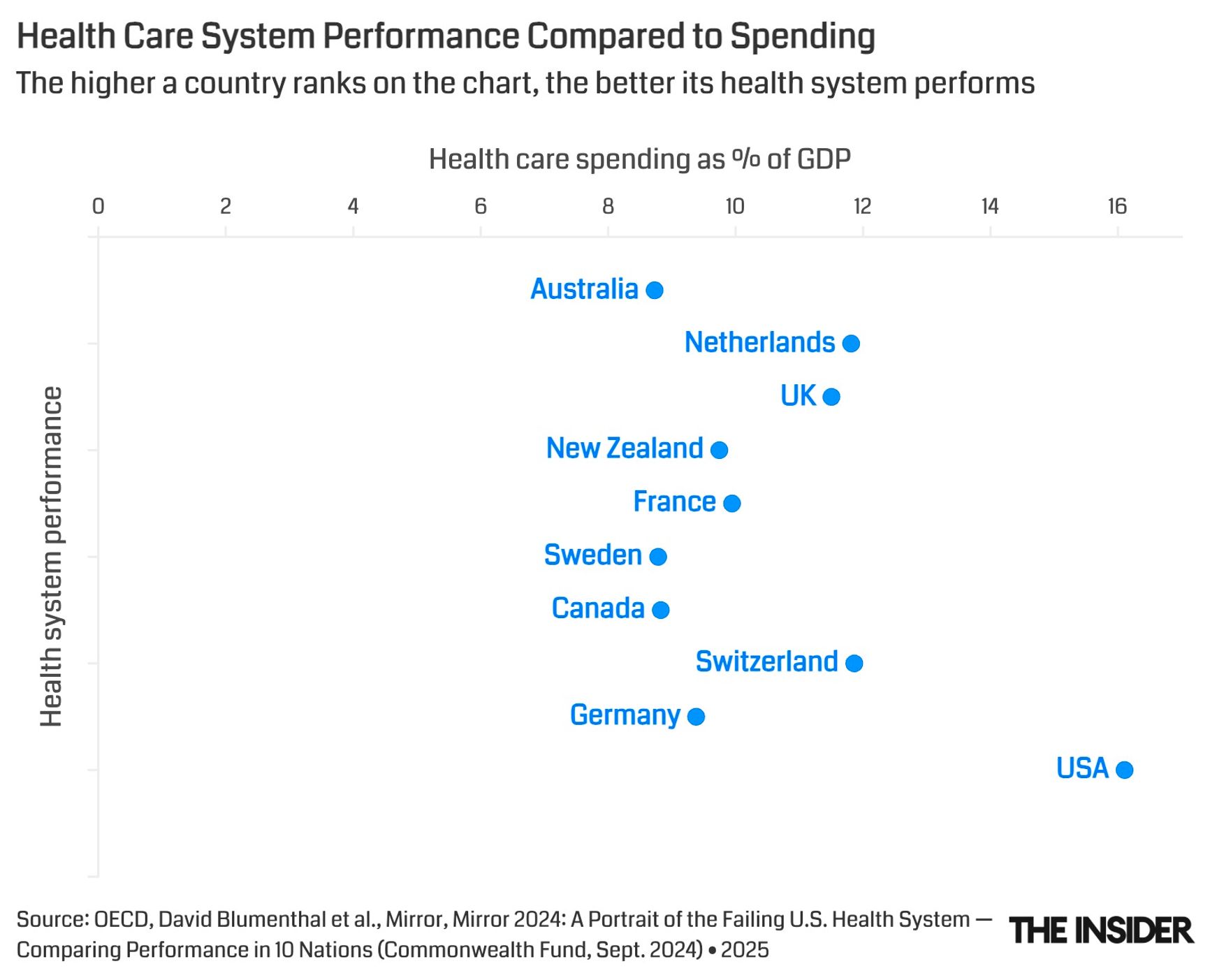

Patients in the United States are more likely to report that they do not have a regular doctor or a designated place to receive medical care. The country’s average life expectancy is four years lower than in the EU. Additionally, the U.S. has the highest rate of preventable and treatable deaths across all age groups — this despite spending more on healthcare than any other country in the world.

Life expectancy in the EU is 81.5 years, but only 77.5 years in the U.S.

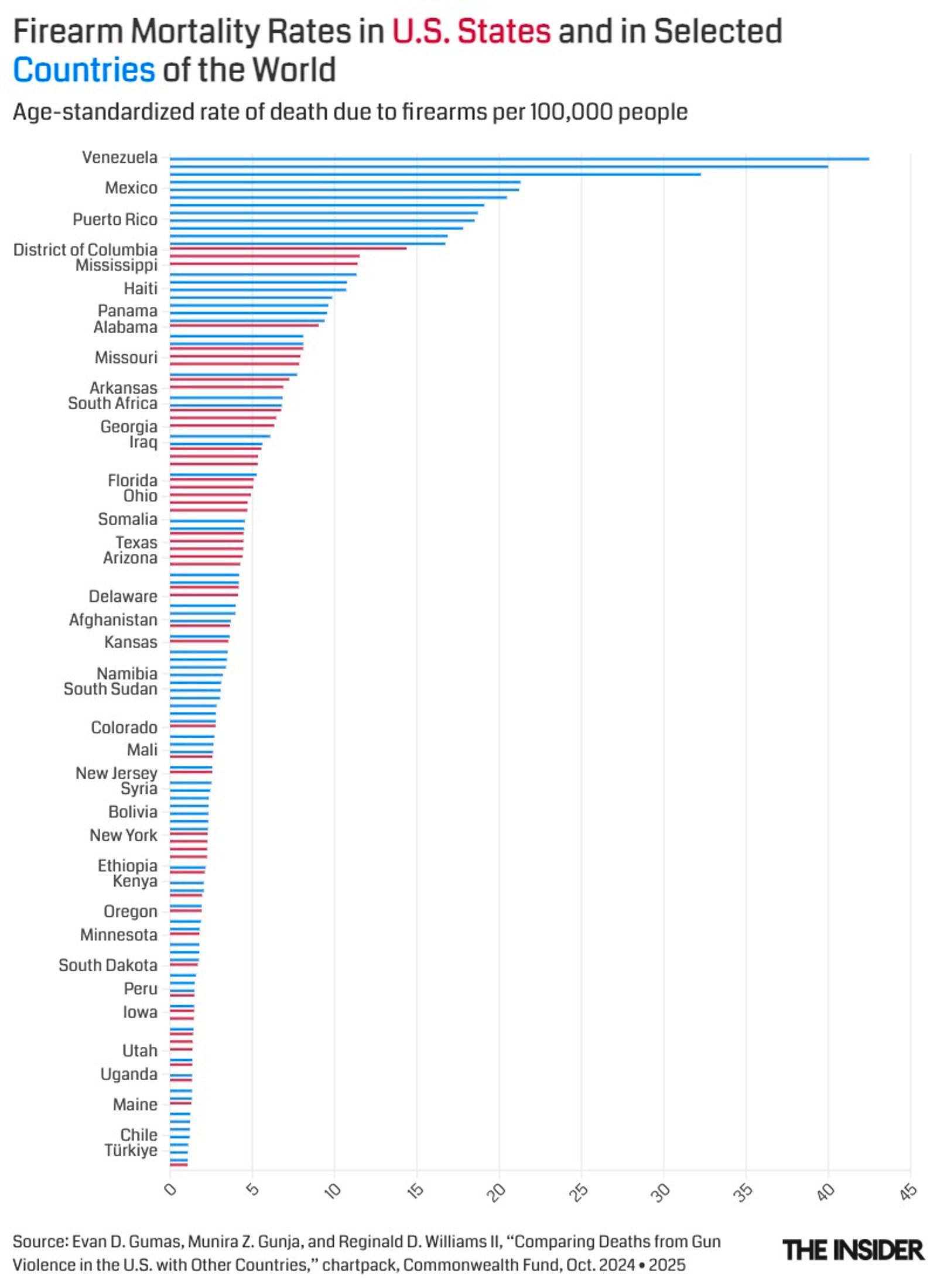

Some medical statistics point to broader social issues rather than simply to problems in the healthcare system. For example, in 2023, the U.S. recorded more than 100,000 overdose deaths and 43,000 firearm-related deaths, figures that far exceed those of other high-income nations.

Safety

Crime rates in the U.S. are significantly higher than in Europe. Across the entire EU, approximately 3,800 homicides are committed annually, while in Texas and California alone, the combined number exceeds 4,200 — nationwide, it surpasses 20,000. Firearm-related death rates in some U.S. states are not only incomparable to those in European countries, they exceed those in nations experiencing active armed conflicts.

This is partly due to the accessibility of firearms: the U.S. has the highest number of gun owners in the world, and regulations on purchase and ownership are far more lenient than in most other countries. This increases the likelihood of violent crimes such as homicides and armed assaults.

In addition, socioeconomic disparities, including income inequality and poverty, particularly in urban areas, play a crucial role in fueling social tensions that contribute to crime rates. The American system’s lack of a strong social safety net exacerbates the problem, as many citizens are left without access to basic services and stable sources of income. With little to lose, some turn to crime. These factors are far less pronounced in many European countries.

Children and motherhood

Social support for motherhood is essential for gender equality. However, in the U.S., there are virtually no free nurseries or kindergartens, and private daycare costs range from $500 to $1,000 per month. With an average monthly salary of about $5,000, this amount may be manageable for middle-income families, but for lower-income households, it is prohibitively expensive.

The lack of affordable childcare also reinforces the cycle of poverty by limiting mothers' career opportunities. In the EU, the situation varies by country, but in most cases, daycare is either accessible to all or heavily subsidized for the most vulnerable populations. Overall, government spending on nurseries and kindergartens in the EU is significantly higher than in the U.S.

Moreover, the U.S. is the only developed country that does not offer paid maternity leave, and free maternity care exists only for the poorest citizens. This issue is further compounded by healthcare challenges, as childbirth can lead to health complications requiring expensive treatment that must be paid out of pocket.

Divided by inequality

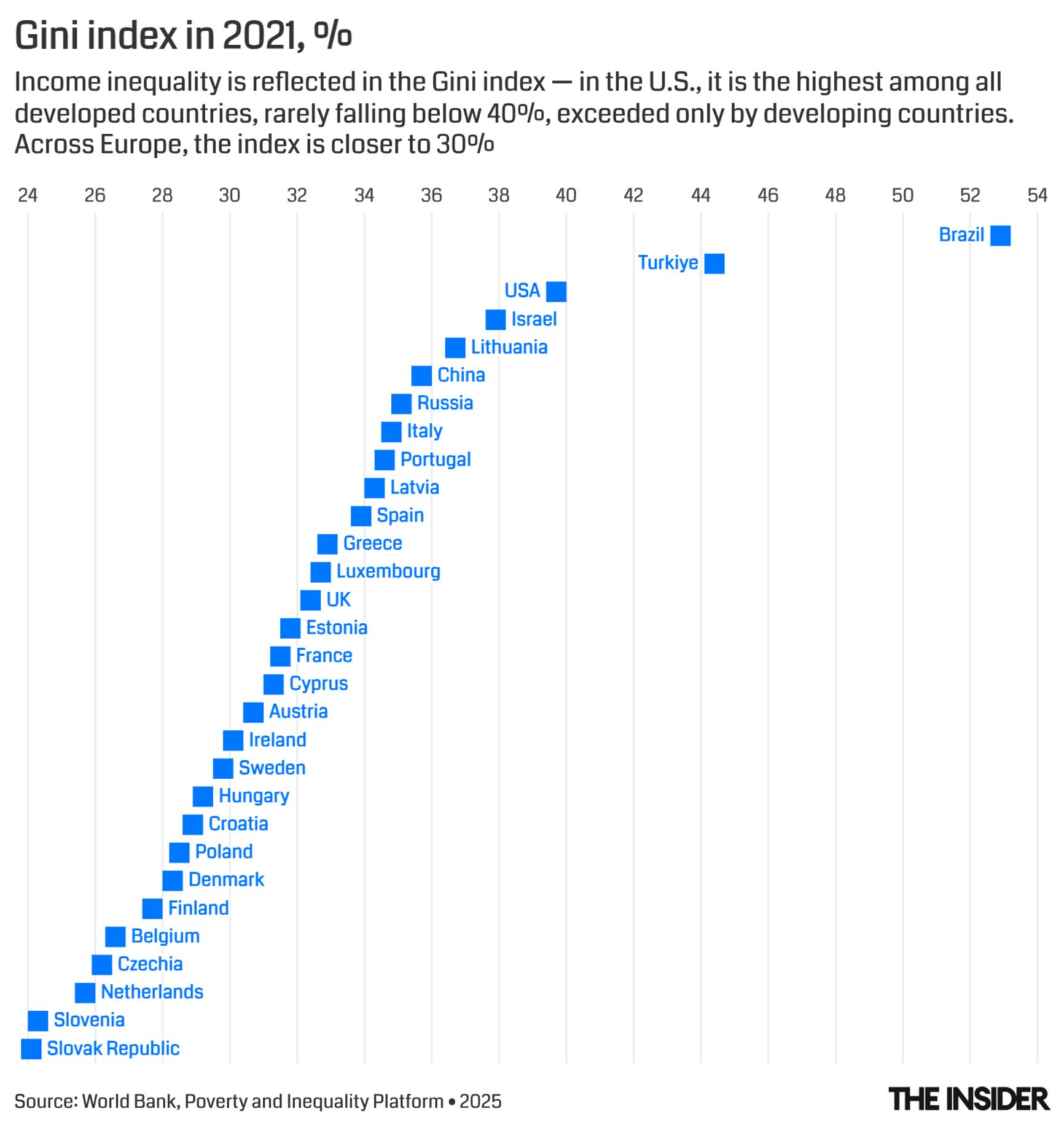

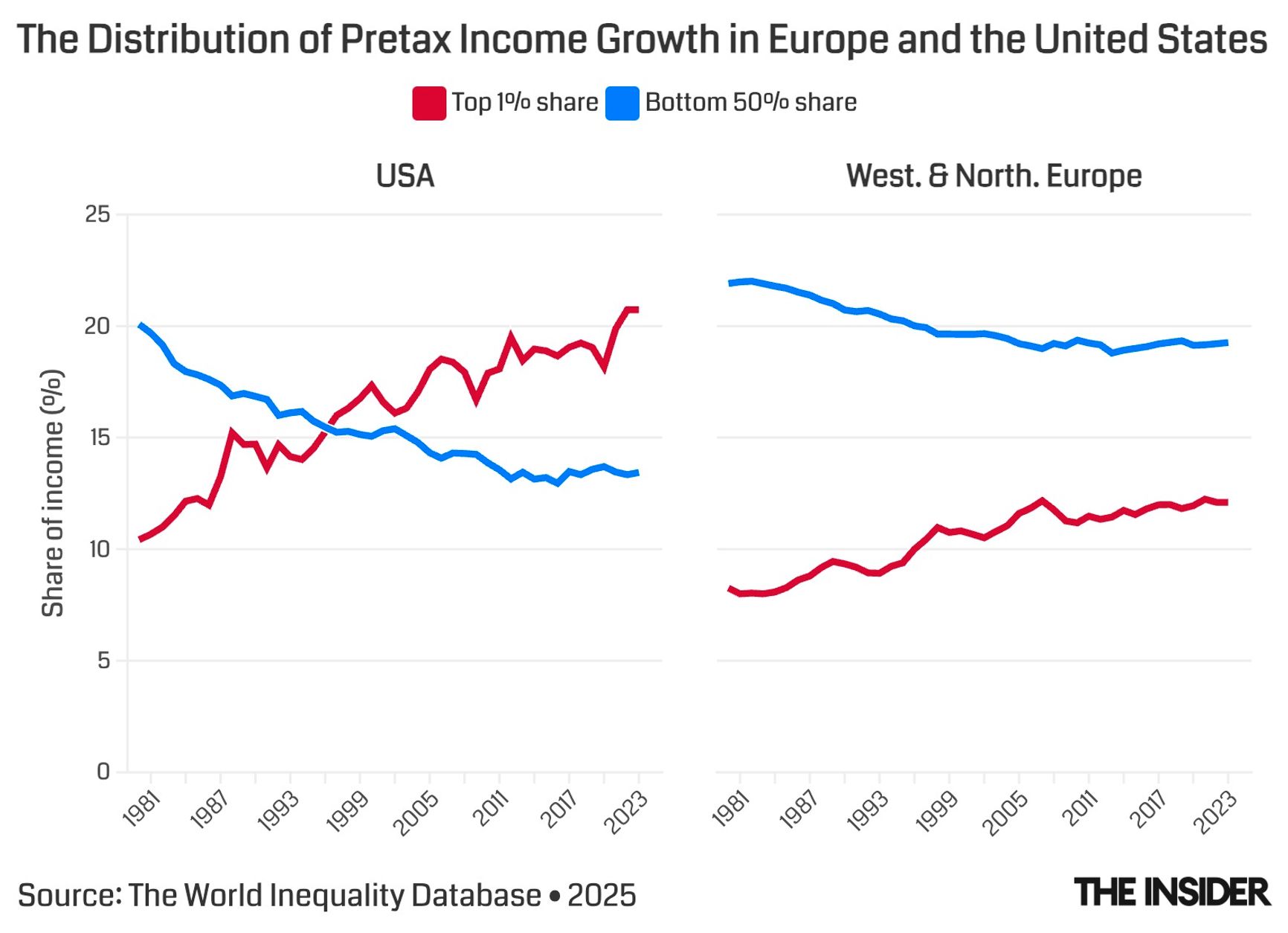

The growth of inequality is observed worldwide, but not at the same pace everywhere. In Europe, the issue is less pronounced, even though as recently as 1980, European countries showed similar figures to the U.S. — the top 1% earned about 10% of national income, while the bottom 50% earned about 20%. Since then, the situation has radically changed. In Europe, the top 1% now earn 12% of income, while in the U.S. it is over 20%. The bottom 50% in Europe now earn 22% of national income, compared to just 11% in the U.S.

Income inequality is reflected in the Gini index — in the U.S., it is the highest among all developed countries, rarely falling below 40%, exceeded only by developing countries. Across Europe, the index is closer to 30%.

The issue is not so much the absence of a progressive tax scale — the tax system redistributes a large portion of income from the super-wealthy to other segments of the population. However, the U.S. has a more unequal situation before taxes, a gap that is not bridged even by budgetary transfers. European countries allocate a significant portion of tax revenues to providing social services, rather than issuing financial payments. Therefore, a high degree of redistribution should be seen as a sign of failure in the sphere of implementing social policies, rather than an achievement in the pursuit of equality.

The rapid rise in inequality in the U.S. is often blamed on globalization and digitization. However, since the 1980s, both Europe and the U.S. have faced similar challenges from expanding markets and developing technologies. But Europe — thanks to differences in policies related to promoting equal opportunity provisions, enforcing anti-monopoly measures, and combating poverty traps — has better managed to control inequality.

It is also worth noting that European countries are leading the fight against climate change, investing an increasing share of GDP into this effort. The green transition can play an important role in reducing inequality both now and in the future, as studies show that environmental degradation and inequality are closely linked — the effects of climate change disproportionately impact the poor, both globally and within countries.

The sweatshop system

The average American still earns more than the average European — $66,000 per year, or $4,500 per month after taxes. In Europe, net salaries are higher only in Switzerland. In Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, the monthly take-home pay is around 3,500 euros. In Germany it is just over 3,000 euros, and the figure in the UK and France is 2,700 euros. However, Americans have to work significantly longer hours: according to OECD data, Americans work one hour more every weekday than Europeans — 1,811 hours per year per American worker, compared to about 1,500 hours in most European countries. In comparison with Germany, where the average worker puts in 1,341 hours annually, an American works almost two extra hours per day.

This difference is not the result of mentality or national character, but of varying labor. Most people in the U.S. work long hours, but they don't enjoy it. According to Gallup, only 31% of American employees are regularly emotionally engaged in their work, while the rest are either indifferent or feel unhappy and actively avoid fulfilling their duties. A significant portion of Americans would likely prefer European working hours, but the unpopularity of unions, the cost of healthcare, the efforts of employers all work against workers.

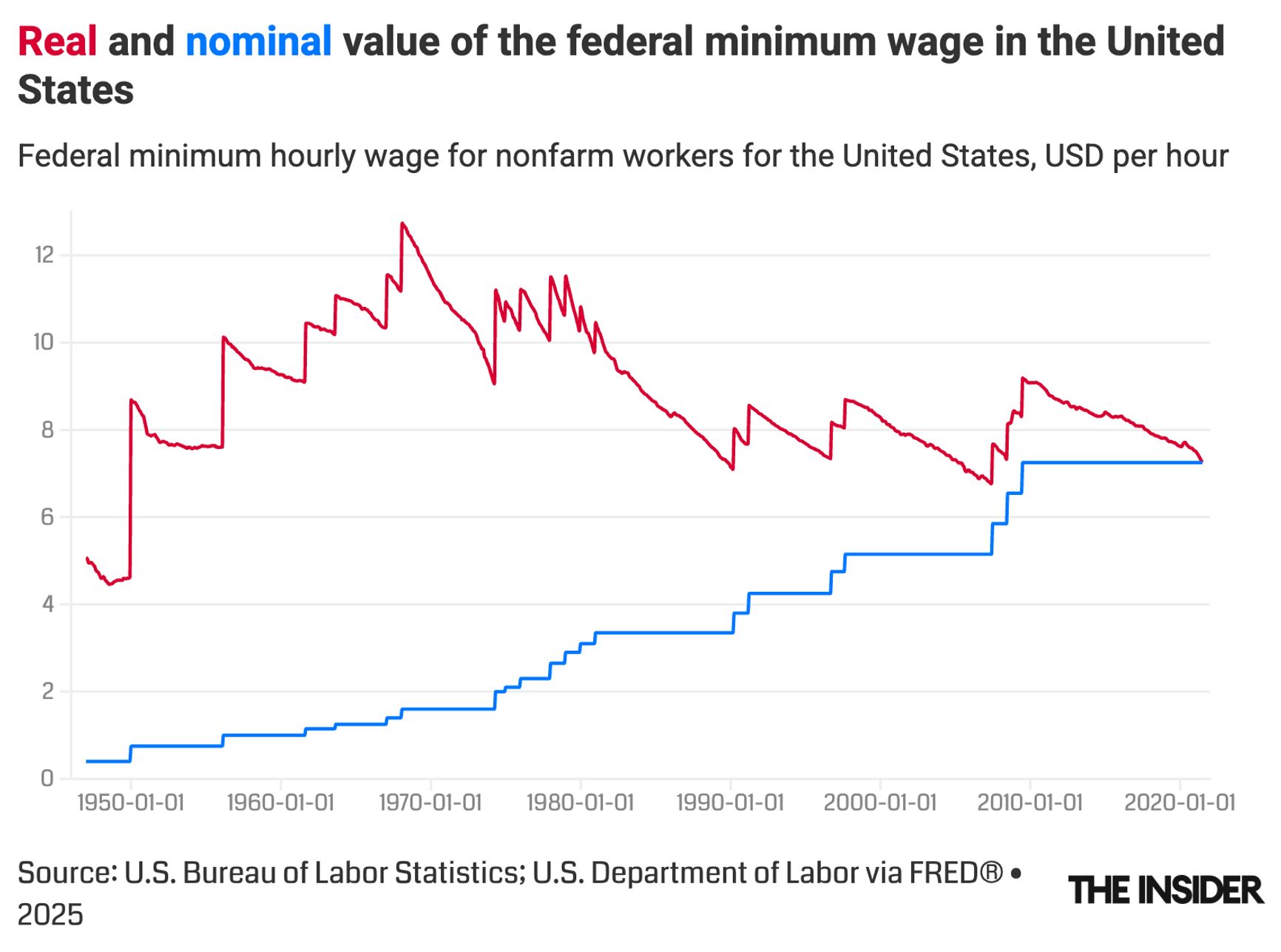

The federal minimum wage in the U.S. has remained unchanged in nominal terms for 15 years, and in real terms, it has decreased by 45% since 1970. Meanwhile in European countries such as France and Germany, the minimum wage regularly outpaces inflation.

The best and most dedicated workaholics in the U.S. can reach truly great heights, but this will always be just a small percentage of all workers. A much larger number, in the end, become overworked and unhappy, even though they have more European-style homes and more expensive cars. In the latest World Happiness Report, the US ranked 23rd, behind many European countries, while Northern European countries with the most progressive labor codes regularly occupy the top spots.

Europeans answer to Elon Musk

In response to Elon Musk's suggestion to make Europe great again, Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk has already spoken up. “Europe was, is, and always will be great,” he declared while speaking at the European Parliament. This sentiment was echoed by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen: “Europe has a unique social market economy. We have the second largest economy and the biggest trading sector in the world. We have longer life expectancy, higher social and environmental standards, and lower inequality than all our global competitors.”

Europe was, is, and always will be great.

Surveys indicate that politicians are reflecting the majority opinion: Europeans were concerned by Trump’s election as president, according to a study by the European Council on Foreign Relations. Residents of the eleven EU countries surveyed, alongside the British, viewed the election results as bad news for Americans. Furthermore, they largely believe Trump’s return to the White House will negatively affect their own countries. In Western Europe, more than 80% of respondents foresee negative consequences for economic growth from Trump's presidency, as shown in a survey by the Institute of Economic Research.

However, opposition within the eleven EU countries named in the survey is uneven — with several in southeastern Europe welcoming Trump's election. “As a result, the EU's efforts to achieve unity in direct opposition to Trump may lead to significant disagreements both between member states and within them,” warns the Council.