On August 25, Russia declared the International Baccalaureate (IB) foundation an “undesirable organization,” accusing it of promoting a “Russophobic stance” and of discrediting Moscow’s army. Dozens of private and public schools in Russia had been working in accordance with the IB’s standards, facilitating their students’ admission to Western universities. Now, Russian principals, teachers, and parents risk facing legal consequences for cooperating with the “undesirable” foundation, and educational institutions themselves are hastily switching to other international educational programs — which may also soon be shut down.

Content

A blow to the elite

What should schools do?

What should students do?

Legal consequences

It came as a surprise when, a few days before the start of the new school year, the office of Russia’s Prosecutor General declared the Swiss International Baccalaureate Foundation an “undesirable organization.” The authorities in Moscow stated that the foundation’s goal was to “shape Russian youth according to Western templates,” and that the essence of its teaching “comes down to imposing its own vision of historical processes, distorting well-known facts, engaging in anti-Russian propaganda, and inciting ethnic hatred.” According to the statement:

“With the start of the special military operation, educational and methodological materials were adjusted to reflect the Russophobic stance of the collective West. They included calls for the international isolation of our country and materials discrediting the Russian army.”

The full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine is not yet mentioned in IB learning materials, even if many teachers working under the foundation’s program may discuss the conflict as one of the topics in the Global Politics course. Still, there are elements of the IB history program that cannot be fitted into the Kremlin’s official propaganda narrative. For instance, the IB section devoted to the origins of World War II devotes considerable attention to the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, with a 2021 exam asking students to comment on a cartoon depicting Hitler and Stalin trampling over a map of Poland.

Stalin’s USSR is studied within the “Authoritarian States” unit, alongside the regimes of Hitler, Mussolini, Castro, Franco, and Mao. The program also includes such topics as the Soviet Union’s postwar control over Eastern European countries, its suppression of the Prague Spring, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

Sergei Kuznetsov, co-founder of the private school Le Sallay, believes that the main reason IB was declared an “undesirable organization” had little to do with the specifics of the curricula — it was the program’s very purpose is to simplify admission to Western universities:

“It doesn’t really matter what they study in history class. The Prosecutor General’s decision is a deliberate move aimed at preventing integration with international institutions and hindering young people from leaving. Why did they resort to designating it as an ‘undesirable organization’? After LGBT was labeled an ‘extremist movement,’ it’s hard to be surprised by anything.”

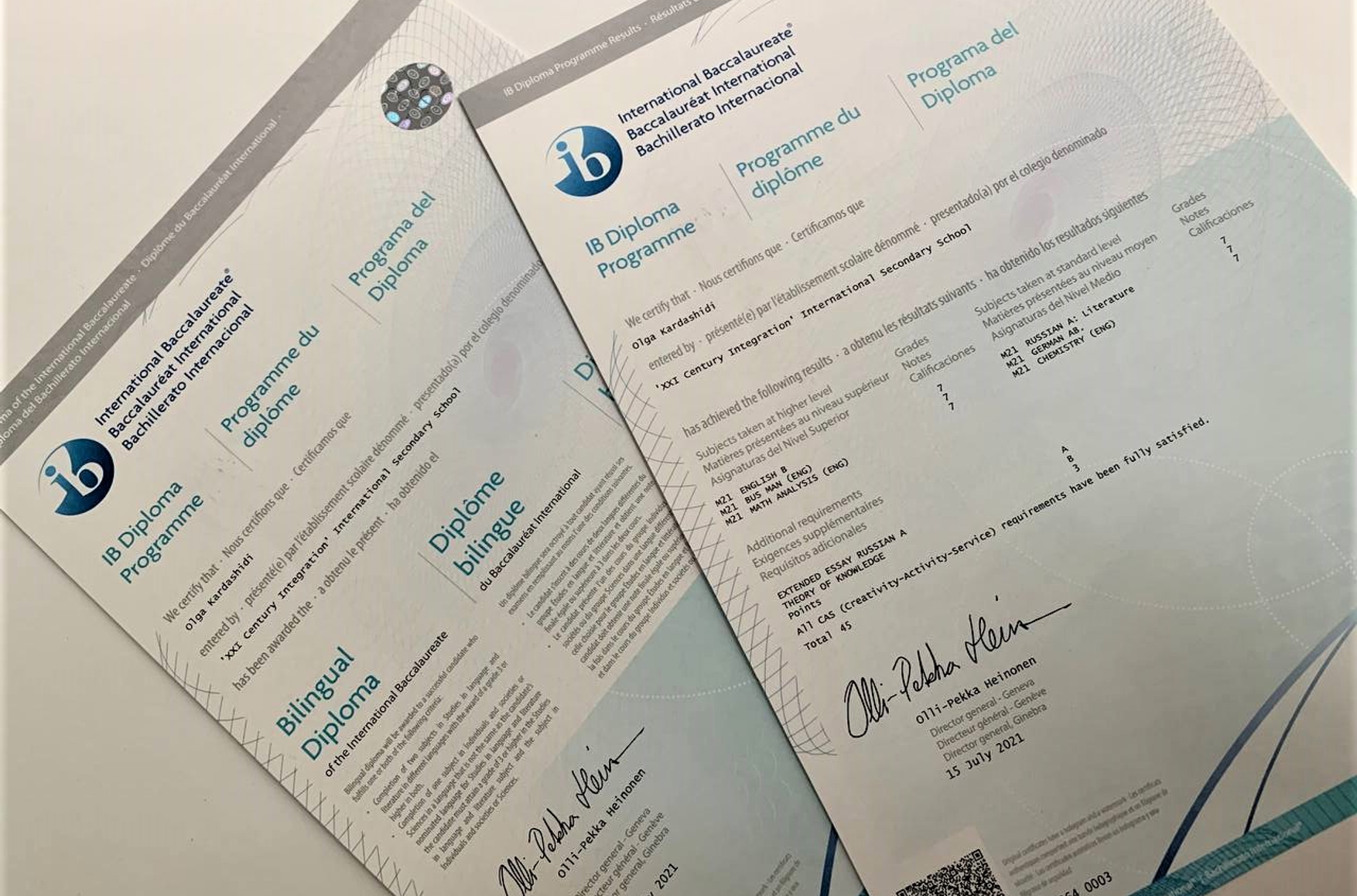

The International Baccalaureate provides programs at the primary, middle, and high school levels. Upon completion, students take exams, the results of which are accepted by around 5,000 universities worldwide. Attitudes toward the International Baccalaureate program began to shift after Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, and even more so after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Kuznetsov notes:

“It remained a legacy of the 1990s and the ‘fat 2000s,’ when it seemed that Moscow was part of the world. A child could study in Russia as the start of a big path toward a foreign university. Now that’s over, the iron curtain is coming down.”

A school with distinctions

Before the full-scale war, around 50 Russian schools worked under the IB system. The first to join the program, back in 1996, was Moscow’s state-run Gymnasium No. 45. Other public schools soon followed, says Igor [name changed at the speaker’s request], a teacher well acquainted with the foundation’s program:

“In Moscow there was a whole movement for state schools to join the International Baccalaureate. After the 45th Gymnasium, many others followed. But participation in IB requires serious effort — major time and financial commitments. Teachers have to be trained, annual fees of $10,000 paid. That was already difficult for public schools, and once the war began, making transfers became almost impossible. I’m sure many schools dropped out of the program partly for that reason.”

As of August 2025, only 29 schools in Russia remained in the IB system, with only 23 of them running the upper school program with international exams.

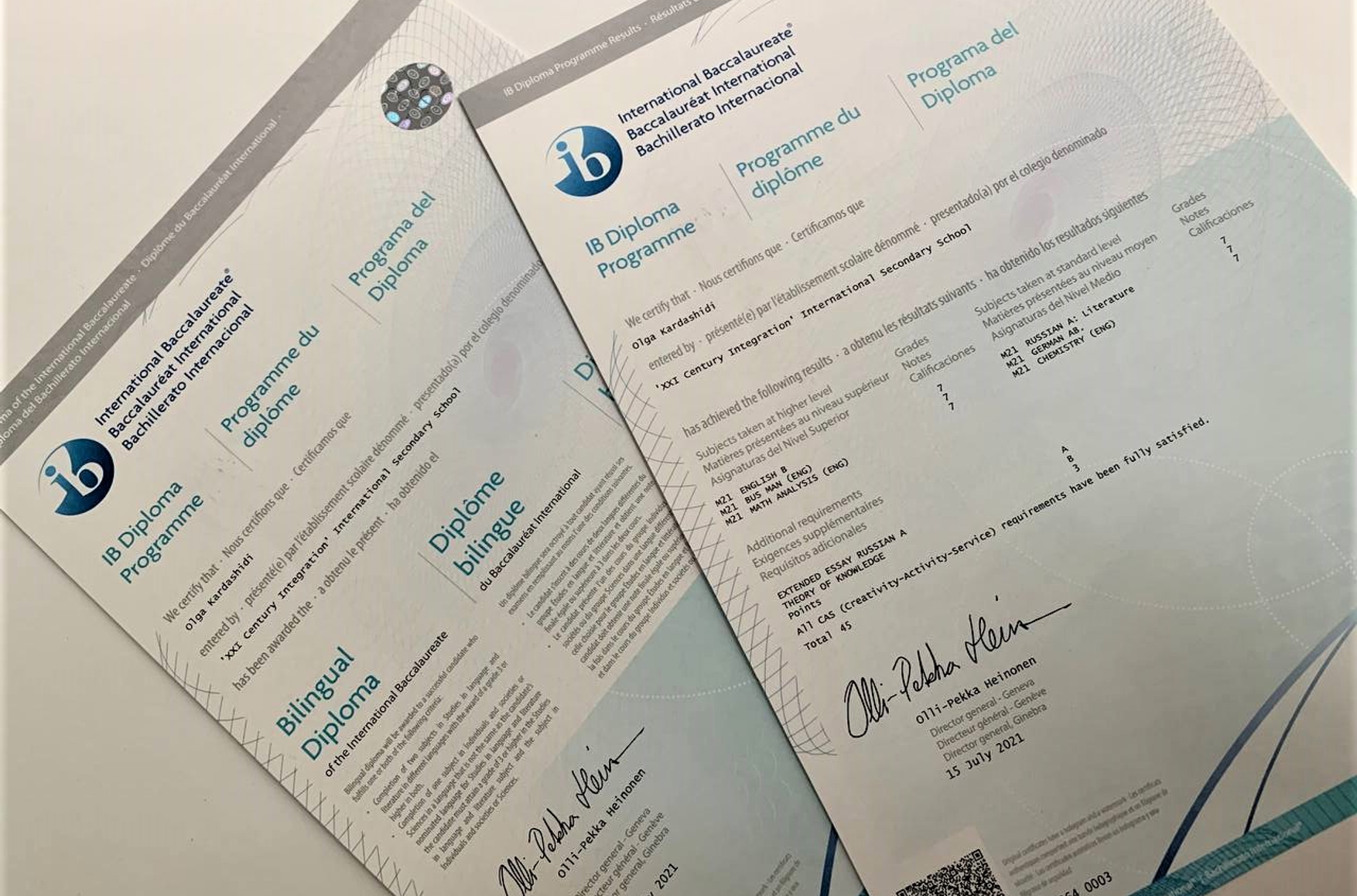

Participation in the International Baccalaureate required schools to overhaul their educational process. For instance, they used a unique seven-point grading system. According to Andrei [name changed], a teacher who worked under IB, the aim of such innovations was to help teachers update their approach to students:

“Teachers are very conservative people. You work at a school for ten years, and in that time math hasn’t changed, Pushkin hasn’t written anything new, the number of oceans and continents is still the same. So what’s the point of rewriting lesson plans? But kids change. And teachers need to change too. You can shorten a class to 35 minutes, or you can, as IB does, change the grading system.”

The program required teachers to keep refreshing their knowledge. This wasn’t about formal professional development, which is largely discredited in Russia. As Andrei explains:

“IB holds international seminars. Every year, teachers in one subject gather to discuss new standards and methods. They don’t just passively listen to important ladies and gentlemen, they come with their own presentations.”

IB teachers gained access to a pool of professional practices from all over the world. As a result, programs in schools that joined IB could meet new international standards that differed greatly from those in Russia, where according to Andrei:

“Standardized textbooks, programs, and teacher training requirements are being introduced. In Moscow they brought in centralized testing, conducted several times a year. At first it was voluntary, then mandatory. And if kids don’t study under the state curriculum, they simply won’t cope with the exams.”

A blow to the elite

Incidentally, the son of former Russian Minister of Culture Vladimir Medinsky — the architect of the country’s unified history textbook — was until recently studying under the IB program at Letovo School. So was the child of Education Minister Sergei Kravtsov, sources told The Insider. However, shortly after the start of the full-scale war in Ukraine, officials transferred their children to other institutions, Andrei says:

“In the school year before last, Medinsky and Kravtsov came to Letovo and tried to talk to the high school students behind closed doors, without teachers. They were very dissatisfied with the conversation and withdrew their children. For members of Russia’s elite, choosing a school has become a political question. And those connected to the authorities make this choice consciously, guided by their own career interests rather than concern for their children’s future.”

It should be noted that schools affiliated with IB are expensive institutions. Even in specialized public schools and lyceums, parents had to pay extra for international exams — quite a large sum for an ordinary family.

The founder of the Letovo school is Russian billionaire Vadim Moshkovich. In March 2025, he was placed in a pre-trial detention center on charges of fraud and abuse of power.

Letovo School

Independent Russian academic platform T-invariant, citing a former head of the International Baccalaureate program in several schools, reported that a year of study in elite public schools cost at least 500,000 rubles (a little over $6,000), while in private schools fees ranged from 1.5 to 2 million ($18,500-$25,000).

Sources for The Insider believe these figures are, if anything, somewhat understated. “Prices varied. Perhaps some public schools could bring them down to 500,000. But the expenses there were still very high,” Igor observes.

Scholarships were available for talented students, including at Letovo. But the majority of pupils in Russia’s IB system were always children of the political and business elite. And it was precisely such families that most often sent their children to study at foreign universities.

The majority of students in Russia’s International Baccalaureate system were always the children of the state and business elite, not all of whom followed the example of Medinsky and Kravtsov, who preemptively withdrew their children from Letovo. Until the IB was declared “undesirable,” the foundation’s programs operated not only in “liberal” schools. For example, even the Pavlovskaya Gymnasium and the Primakov Gymnasium, both known for their “patriotic spirit,” retained IB accreditation. Now, even they will have to overhaul their curricula.

What should schools do?

Not all schools that worked under IB were willing to disclose their future plans. The British International School in Moscow told RBC that immediately after the Prosecutor General’s decision, it dropped IB programs and switched to the similar British A-Level system.

The founder of the Letovo school is Russian billionaire Vadim Moshkovich. In March 2025, he was placed in a pre-trial detention center on charges of fraud and abuse of power.

Immediately after the Prosecutor General’s decision, many schools abandoned IB programs and switched to similar systems of education that are not yet banned

A-Level differs in that high school students choose several subjects for in-depth study and take exams specifically in them. Grades under this system are also accepted by Western universities — not only in the UK, but also in the U.S., Canada, and a selection of universities in continental Europe. The choice of universities is smaller, but for many families, it is sufficient.

The head of a Moscow school told the education portal Mel that many of his colleagues see A-Level as the main alternative to the International Baccalaureate. Niyaz Gafiyatullin, principal of the International School of Kazan, said that his institution, which until recently worked under IB programs, does not plan to switch to the British option:

“As far as I know, this is part of the Cambridge system, which withdrew its support from Russian schools. We don’t want to cling to a system that has turned its back on us. So we don’t view A-Level as a full-fledged alternative to IB. But if a family wants to prepare for A-Level exams, the school will help and support them. At this point, taking exams under this program is not punished, not prosecuted, and is not a violation.”

Sources for The Insider, however, believe that after the IB ban, A-Level is also likely to be shut down. The underlying purpose of the restrictions, Andrei argues, is to eliminate all “alien” educational programs:

“All other systems are seen as a threat to national security and national unity. So switching to A-Level is a questionable measure. Maybe schools will gain another year. Or maybe not even that. Officials hear a new word and start acting.”

Gafiyatullin is confident his school will manage to rework its program within two weeks, leaving no trace of IB. But in teacher chat groups, panic is still the dominant mood. The ban on the International Baccalaureate came as a complete surprise to the professional community.

What should students do?

Since IB was declared “undesirable” just a week before the start of the school year, many school administrators fear parents will withdraw their children, Andrei notes. He adds:

“But on the other hand, where can they scatter to in a week? It’s coming down to the kids either switching to the regular program, moving to remote or homeschooling, or going abroad.”

Gafiyatullin also expects an outflow of students abroad. IB programs, after all, provide for an easy transfer to any school in the world that uses the system.

Another problem is that after studying under IB programs, it is harder to pass Russia’s Unified State Exam (EGE), especially in subjects like history, which is taught very differently in ordinary Russian schools. Students who spent one year in the international program and are now entering 11th grade, Igor says, face a very difficult situation. In his view, the workable option for such students is to move to a country with a 12-year school system and complete an extra year there:

“That said, kids in this situation are just a drop in the ocean. In a regular school, no more than a dozen students were in the graduating IB class. In a big school like Letovo, maybe forty. How many such students are there across the whole country? Two hundred, three hundred, maybe four hundred?”

For the state elite, there is another solution: schooling in China. After February 2022, many officials moved their children there, Andrei says. The children of Russia’s upper echelon study in Chinese branches of Oxford and Cambridge — in the English language and under British professors. After graduating from such schools, it is easy to get into popular global universities — but formally it is Chinese education, which has nothing to do with the West.

Legal consequences

It is possible that many of the affected students will now take International Baccalaureate exams abroad. A similar situation occurred with the IELTS language test, which stopped being administered in Russia shortly after the start of the full-scale war.

Taking IELTS itself remained legal until June 5, 2025, when the Prosecutor General’s Office declared the British Council, which conducts the exam, an “undesirable organization.” Now, paying to take the test could be interpreted as financing an “undesirable organization” — just like paying for IB exams after August 25.

The founder of the Letovo school is Russian billionaire Vadim Moshkovich. In March 2025, he was placed in a pre-trial detention center on charges of fraud and abuse of power.

The British Council, which organized the IELTS language exams, ceased operations in Russia after being declared “undesirable”

The Prosecutor General’s decision entails a blanket ban on international cooperation by educational institutions — from hosting events and distributing materials in Russia to making financial transfers to organizations. However, the complexities may leave room for parents to continue paying for IB lessons, explains the legal department of OVD-Info:

“International Baccalaureate is a program developer and quality regulator that authorizes independent schools. To teach under IB, a school becomes accredited and pays the foundation separate fees. At the same time, the school remains an independent legal entity and is not a subdivision of IB, meaning it is an external counterparty under contract. Therefore, formally, paying tuition to a school is not the same as financing IB.”

Still, due to the broad Russian prosecutorial practice of punishing even tangential interactions with “undesirable organizations,” it is safer to avoid any actions that could be interpreted as supporting IB’s activities in Russia: participating in its events, distributing its materials and symbols, or providing funding. As for timing, the provisions on “undesirable organizations” do not apply retroactively. “Enrolling a child in IB abroad and payments made before the publication of the decision do not entail liability, at least not under criminal law,” the lawyers note.

The founder of the Letovo school is Russian billionaire Vadim Moshkovich. In March 2025, he was placed in a pre-trial detention center on charges of fraud and abuse of power.

Lawyers advise excluding any actions that could be interpreted as supporting the activities of the International Baccalaureate in Russia

However, a Russian court may consider online publications related to IB to be an offense, even if they were published before the policy change was announced. The same logic applies as in cases where Russians are punished for old posts about organizations later declared “extremist.” Thus, even mentioning the International Baccalaureate in Russia may now result in a fine for “participation in the activities of an undesirable organization.” A repeat “violation” within a year could already lead to criminal prosecution under the criminal article on participation in “undesirable organizations.”

Could a Russian student studying abroad under the IB program be prosecuted for “cooperation with an undesirable organization”? There is no clear answer, OVD-Info acknowledges:

“The risk remains in any case, especially if the child plans to return to Russia and continue studying here. One should assume that virtually any interaction with foreign entities may eventually be criminalized in Russia.”

OVD-Info lawyers also believe that schools previously authorized by IB are in danger. They could be classified as “structural subdivisions of an undesirable organization,” even if formally independent. The risk of such an assessment increases if IB branding (“IB World School” on signs and websites) is retained and if its teaching materials are used systematically.

Even without being legally declared “undesirable,” private schools face serious risks. In recent years, security agencies have increased inspections of private educational institutions, notes Andrey:

“They check everything — from curricula to fire safety. Private schools are a convenient target for officials. So in IB-related chats, the mood is grim. People are relieved that they haven’t been blacklisted yet, but they understand their work carries risk. Some schools don’t tell anyone they have any international program. They’ve gathered some materials from abroad, invented some things themselves. But they’re next — they’ll come for everyone.”

The founder of the Letovo school is Russian billionaire Vadim Moshkovich. In March 2025, he was placed in a pre-trial detention center on charges of fraud and abuse of power.