Russian political prisoners are being handed additional sentences on a massive scale. One of the best-known examples is that of Alexei Gorinov, an anti-war municipal deputy who in July 2022 was given seven years for “discrediting” the Russian military. This past November, based on testimony from inmates who were working as informants, Gorinov was found guilty of “justification of terrorism.” Although the new verdict only added one year to the term he is set to spend in incarceration, it led to his transfer to a maximum security prison. Many other political prisoners, including Azat Miftakhov and Maria Ponomarenko, have faced similar treatment. Lawyers and human rights defenders interviewed by The Insider advise prisoners against discussing sensitive topics with their cellmates and recommend ignoring provocations from prison employees. Still, there is no way to ensure one’s complete safety against a state apparatus notorious for bringing politically motivated cases.

Content

“Justifying terrorism”: Cases built on cellmates' testimony

“Disrupting the functioning of the penal colony”: How any physical contact with a prison officer can turn into a criminal case

Local initiative or orders from above: Who decides the fate of prisoners?

Perks, pressure, and blackmail: how prisoners are turned into “witnesses”

How political prisoners can defend themselves: A legal perspective

Over the past two years, the practice of initiating new criminal proceedings against convicts in political cases has become commonplace. Russia’s state security organs are increasingly using charges such as “disrupting the functioning of the penal colony” and “justifying terrorism” in order to extend prison sentences, tighten detention conditions, and demoralize inmates. The vast majority of such cases are initiated against those convicted on political charges.

The Insider analyzed dozens of verdicts and spoke with lawyers and human rights advocates to figure out how the system works, who controls it, and whether it can be countered.

“Justifying terrorism”: Cases built on cellmates' testimony

Under Russian law, any mention of actions taken by third parties against the state’s security forces or military can be interpreted as “justification of terrorism” provided that the speaker does not explicitly condemn the action in question. As a result, “justification of terrorism” has become a convenient statute for the Federal Security Service (FSB) to use when targeting opponents of the Putin regime. Outside prison, the “evidence” presented in such cases is rarely anything more serious than online posts and comments. Inside detention facilities, material is frequently gathered by inmates acting as informants, who engage political prisoners in conversations on controversial topics, then report back to the authorities.

Most Russian pretrial detention centers or penal colonies hold anywhere from several hundred to over a thousand detainees, who interact with one another almost around the clock. Unlike in cyberspace, it is impossible to monitor every subversive statement made by an inmate using technical means. As a result, this function is carried out by the “informant system,” explains Olga Romanova, head of the Russia Behind Bars Foundation, in an interview with The Insider.

In some cases, the prison administration may install a listening device in the cell, but mostly they coerce inmates into cooperating with the authorities, then use them as witnesses for the prosecution. This is what happened in the case of mathematician and anarchist Azat Miftakhov. In September 2023, Miftakhov was due to be released after serving 4.5 years over an act of “hooliganism” involving a broken window at the ruling United Russia party’s Moscow headquarters (a crime he denied committing). However, upon leaving the penal colony, Miftakhov was immediately detained on “justification of terrorism” charges stemming from a phrase he had allegedly uttered to another inmate while watching television.

Azat Miftakhov

The Insider reviewed the new case against Miftakhov and found that it was based solely on the testimonies of three inmates, all of whom repeated the phrase that the political prisoner had allegedly said in May 2023. For the court, that was enough to sentence Miftakhov to four more years in prison.

In other cases, a prisoner who is being “worked on” (slang for targeted in a fabricated case) may be placed in a cell equipped with hidden surveillance and populated by prison administration agents. These agents engage the inmate in provocative conversations for hours or even days. The recordings are then sent for expert analysis, which extracts a handful of words to serve as the basis for new criminal proceedings. This is what happened to political prisoners Alexei Gorinov and Andrei Petrauskas.

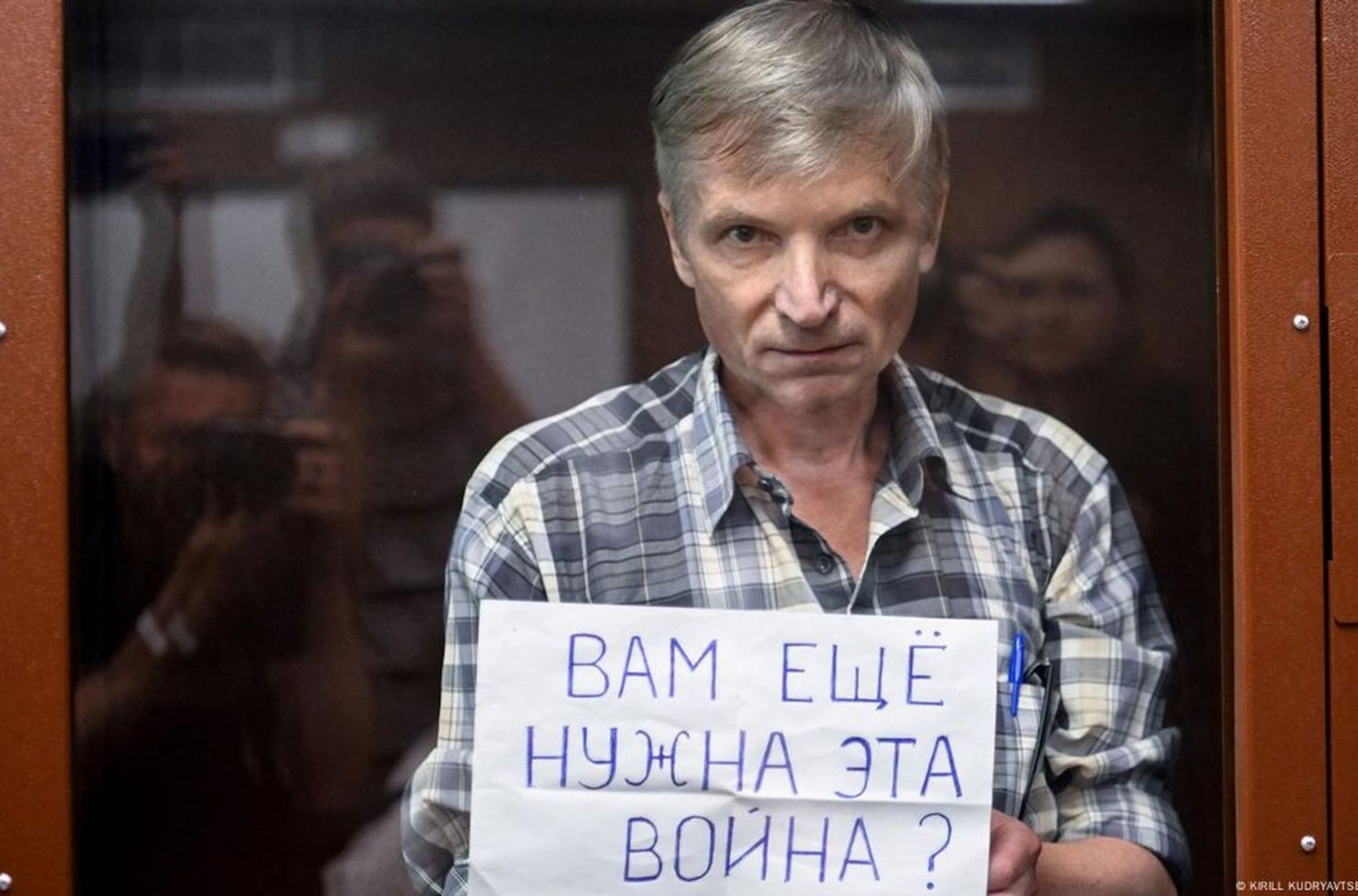

Alexei Gorinov holding a sign “Do you still need this war?”

In the fall of 2023, a second criminal case was filed against former municipal deputy Alexei Gorinov, who in July 2022 had been sentenced to seven years in prison on charges of spreading “fake news” about the Russian army. On Dec. 31, 2022, Gorinov was transferred to a ward in the prison hospital populated with repeat offenders. A television in the room constantly broadcast the news, and his cellmates coaxed Gorinov into discussing what he saw. Meanwhile, his every word was being recorded.

The recordings and testimonies of his cellmates became the basis for charging Gorinov with “justifying” Ukraine’s October 2022 attack on the Kerch Bridge and the actions of the Ukrainian Azov Battalion — which in Russia is designated as a terrorist organization. In the new case, the court sentenced Gorinov to three years in prison and reclassified his incarceration from a general-security to a high-security prison. His total sentence was set at five years in a high-security facility.

A similar approach was used in the case against Andrii Petrauskas, who was sentenced to 10 years in prison for setting fire to a military enlistment office in Krasnoyarsk. In his case, the interlocutors were Ukrainians Yurii Domanchuk and Artem Krykunov. Domanchuk had been sentenced to 23 years for an attempted attack on a Russian official in Kherson, and Krykunov to five years for “preparing a terrorist act” in the occupied part of the Luhansk Region.

Case materials reviewed by The Insider suggest that conversations between Petrauskas, Domanchuk, and Krykunov were recorded over the course of several days. Petrauskas and Domanchuk were doing most of the talking, while Krykunov spoke little. The psychological and linguistic examination concluded that Petrauskas had justified the activities of the Freedom of Russia Legion and the Artpodgotovka movement, both of which are also designated as terrorist organizations in Russia. Petrauskas pleaded guilty, and the court sentenced him to an additional 2.5 years, increasing his total prison term by a year and a half.

Inmates convicted under non-political charges are also not immune to fabricated cases of “justifying terrorism.” In May 2025, the 2nd Eastern District Military Court — one of nine Russian courts handling “terrorism-related” cases — issued two sentences to prisoners of Penal Colony No. 2 in the Trans-Baikal Territory.

One of them was Mukhadin Tokhsarov, 43, from Kabardino-Balkaria, who was sentenced to 20 years in prison for a double murder. According to the court, during conversations with his cellmates Tokhsarov justified the actions of the Taliban, of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (both recognized as terrorist organizations in Russia), and of the militants who seized School No. 1 in Beslan, Chechnya, in 2004.

The second defendant is Ivan Praskov, 40, from the village of Kharagun in the Zabaykalsky Krai. Praskov was previously convicted of armed robbery, fraud, assaulting a law enforcement officer, and insulting a judge. The court’s press release regarding his latest guilty verdict does not even specify what Praskov was accused of “justifying.” It merely states that “in conversations with other inmates, he publicly expressed support for the ideology and practice of terrorism, describing them as correct, worthy of support and emulation, and justified and promoted terrorist activities as well as acts of a terrorist nature.”

The court’s press release does not even specify what the inmate was accused of “justifying,” as if it were a case of abstract terrorism

Such cases show that, from a technical standpoint, filing new charges against an inmate is easy. There is no need to search for evidence or witnesses — a couple of testimonies from other prisoners or recordings of conversations is enough. Even a casual remark can be interpreted as a crime in the event that the authorities are looking for a pretext. As a result, charges of “justifying terrorism” become a convenient tool for exerting pressure, keeping someone in prison, or simply demonstrating power.

“Disrupting the functioning of the penal colony”: How any physical contact with a prison officer can turn into a criminal case

This past March, political prisoner and journalist Maria Ponomarenko was sentenced to a new prison term for “disrupting the functioning of the penal colony.” According to the court, Ponomarenko refused to appear before a disciplinary commission that was expected to issue a penalty — most likely, to place her in a punishment cell. Colony officers tried to bring her there by force, and she allegedly attacked them. The journalist denied the charges, stating that she was the one who had suffered abuse from the guards, who had choked her with a pillow and slammed her head against the floor.

Maria Ponomarenko

This statute has been used against political prisoners before. The first widely known case of “disrupting the functioning of the penal colony” was opened in 2016 against activist Sergei Mokhnatkin while he was serving a sentence in Penal Colony No. 4 in the Arkhangelsk Region after being convicted of using non-lethal force against a police officer during the Strategy 31 protest on Dec. 31, 2013. In March 2016, colony officers beat the 62-year-old Mokhnatkin after he refused to be transferred to a pre-trial detention center. He sustained multiple spinal fractures. Criminal proceedings were initiated against Mokhnatkin himself; he was charged with assaulting the prison staff.

Under the new charges, Mokhnatkin was sentenced to two years in prison. While incarcerated, he did not receive necessary medical treatment and only began therapy after his release in 2018. The consequences of his spinal injury worsened: he lost the ability to walk, and in 2020, he died due to complications from surgery.

In 2024, similar charges were brought against Zarema Musaeva, the mother of the founders of the Chechen opposition channel 1ADAT. According to investigators, she struck a Federal Penitentiary Service officer and tore off his shoulder strap while riding in a car with him after receiving medical treatment at a hospital. Musaeva denies the charges.

Zarema Musaeva

The article on “disrupting the activities of institutions” is also used against non-political prisoners. In January 2018, Ruslan Saidov, who was serving a 10-year sentence in Norilsk’s Penal Colony No. 15 for theft, rape, and assaulting a judge, was sentenced to an additional 7.5 years under the new charge. The court ruled that he had used “life-threatening violence” against a colony officer.

The incident occurred when Saidov was being searched during transfer to a punishment cell. The prisoner refused to remove his underwear, appealing to his personal dignity and religious beliefs. The guards grabbed his hands and forcibly undressed him. After the search, Saidov was given back his underwear, and, in the words of the verdict, “threw them in the officer’s face saying ‘choke on them,’ and then punched him in the eye.”

Saidov himself claims that he merely waved the guard's hand away, frightened that he was about to be beaten. He also stated that the search had been an act of abuse and a possible unlawful provocation carried out with the intent of inspiring a reaction. His complaints were ignored, and the video footage presented by the prosecution showed only selected moments of the incident.

Unlike cases of “justifying terrorism,” which rely entirely on words and interpretations, cases of “disruption” usually involve physical contact — but that does not make them any less effective for the purposes of fabrication. The threshold for opening a case is minimal — it is enough to touch an officer, to refuse to comply with a humiliating demand, or to simply be “inconvenient” for the administration. The evidence base in such cases is almost always formed from the testimonies of the colony staff themselves, which makes the prosecution’s version of events almost impossible to disprove.

All it takes for an inmate to be charged with “disrupting the functioning of the penal colony” is to touch an officer or refuse to comply with a humiliating demand

In this setting, any interaction with prison officers is a risk — especially for inmates already labeled as “problematic” or “political.” Charges of “disruption” turn into a universal tool of pressure: to punish, isolate, extend sentences, or demoralize prisoners.

Local initiative or orders from above: Who decides the fate of prisoners?

Who needs new cases against those who are already serving sentences, and for what purpose are they opened? As lawyers and human rights defenders point out, the number of new criminal cases is one of the KPIs for operational units within multiple state organs — the FSB, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Investigative Committee, and the Federal Penitentiary Service.

Olga Romanova believes that the abundance of cases initiated against inmates is connected with the incentive structure of the Federal Penitentiary Service:

“The main service within [Russia's] Federal Penitentiary Service is the operational service. Russia is practically the only country in the world where the primary department [of the penitentiary system] is not social, medical, or educational, but operational. The first deputy in any institution is always the deputy for security and operational work. What kind of operational work is being done in prison? Extracting confessions, obtaining admissions of guilt, solving crimes. The more new sentences they add, the more ‘findings’ they deliver, the better it is for them. And when there is nothing to be found, they make cases from scratch.”

In addition, Romanova has observed clear signs that a directive has come “from above” in order to extend the sentences of political prisoners: “It feels like someone gave an order. We’re recording a rise in such cases — over the past year and a half, in 2024 and part of 2025, there have already been more than 100 instances. And that’s just under political charges.”

Nevertheless, Romanova believes that when it comes to opening new criminal cases against inmates, the initiative more often comes from prison system operatives, rather than from Moscow.

However, Yevgeny Smirnov, a lawyer with the human rights group Pervy Otdel (Dept. One), is convinced that in cases involving well-known political prisoners such as Azat Miftakhov or Zarema Musaeva, the initiative came from the FSB or the Center for Combating Extremism rather than from the Federal Penitentiary Service (FSIN). “I don’t think local FSIN operatives are allowed to make decisions in such cases,” Smirnov told The Insider. “High-profile cases like these are usually overseen by those who initiated them: either the police or the security services. And they monitor such convicts throughout their sentence. New cases against such prisoners would hardly be possible without the FSB’s approval.”

According to Smirnov, new criminal cases are initiated against political prisoners to put pressure on them and send a message about the futility of any resistance. As the lawyer notes, a new conviction leads to harsher prison conditions, as the fact of the new verdict allows the inmate to qualify as a repeat offender:

“A stricter security regime, fewer packages, fewer visits and phone calls with relatives. It’s a legal way to make the incarceration conditions less humane.”

Perks, pressure, and blackmail: how prisoners are turned into “witnesses”

Cases of “disruption” are built on the testimony of “injured” staff members, with the “victims” and their colleagues serving as witnesses in court. Their motivation is clear: professional solidarity, obedience to superiors who gave the orders, and a negative attitude toward prisoners in general.

However, cases of “justifying terrorism” rely mostly on the testimony of other inmates. A lawyer working on such cases told The Insider anonymously that FSIN officers recruit prisoners by offering them small favors — or by blackmailing them:

“Some are allowed to make an extra phone call, others get tea, some get to smoke, others get an extra five minutes outside or a trip to a civilian hospital. Or they say, ‘We won’t tell anyone anything compromising about you.’ It’s a typical web of police intrigues they constantly weave. This isn’t limited to political prisoners — they’ve been doing it their whole lives. That’s their method of work.”

To recruit prisoners, FSIN officers offer prisoners small favors — or blackmail them

Lawyer Yevgeny Smirnov notes that prisoners are completely under the administration’s control and may give testimony under pressure:

“They are people under duress. They are completely at the disposal of the prison administration, and refusal to cooperate can bring all sorts of consequences, from minor deterioration of prison conditions to torture. One can recall Alexei Navalny during his time in the first colony. The administration managed to break every prisoner who had contact with him. Prisoners were forbidden from communicating with him, helping him, or offering any support. It wasn’t just one, two, or even ten people. Finding several prisoners who are willing to start a conversation, so that every word can be recorded with a hidden camera, is not difficult.”

Olga Romanova notes that prison officials use a variety of methods to persuade inmates to cooperate with the authorities:

“Some prisoners cooperate in exchange for leniency: to avoid beatings, to be put in charge, to gain power within the unit, to be allowed extra visits, or a chance at early release — although they are often deceived when it comes to early release. But even avoiding a beating is already a strong incentive. Moreover, they get to beat others, and as long as you beat others, you won’t be beaten yourself. Another powerful recruitment tool is sexualized violence: prisoners, especially those who have family in the Caucasus, agree to cooperate if threatened with rape — or with the publication of footage of their rape.”

How political prisoners can defend themselves: A legal perspective

In short, fabricating a new criminal case against a prisoner is a fairly straightforward process: the administration can easily find “witnesses” from among a target’s fellow inmates to testify about how they “justified terrorism,” or else they can provoke the prisoner by using force against them until they make an attempt to defend themselves.

“If you’re a political prisoner, there’s little you can do,” Romanova says. “Take Gorinov’s case. He’s one of the calmest people I've seen. They have 16 hours of recordings, and in the end, all they found was five or eight words. They kept him talking for weeks — and eventually found grounds to extend his sentence. If you don’t talk at all, they’ll come and write: ‘He attacked a staff member.’ And they'll make sure to find witnesses.”

Yevgeny Smirnov advises inmates to pay attention to cellmates and to “watch your language”:

“There are no specific rules that guarantee your safety. You have to rely on your intuition, avoid dangerous conversation topics, and be cautious with cellmates who bring them up. It is common practice [in criminal investigations] to plant agents in cells, so that they can gain the defendant's trust and ask them to talk about their case. The same applies here — agents gain prisoners' trust and initiate conversations about things that are forbidden to discuss in Russia: the war, mobilization, the political regime, and events labeled by the authorities as terrorist acts. Talking about these things is dangerous and poses a great risk to people. So you have to be careful and think before you speak, even in the colony.”

A lawyer who works on cases against prisoners emphasizes the importance of using an abundance of caution: “A defendant must be told before they get to the pre-trial detention center that they must not talk to anyone about anything — except maybe the weather or the green grass outside the window. Nothing else. One of my clients told me that some people stay silent for three days straight, then whisper something in a corner to someone they trust, and then go back to silence. That’s the right approach if you want to avoid getting slapped with a new case.”

As for cases of “disruption,” the lawyer believes that many times the charges are in fact based on actual misconduct. He emphasizes that it’s important to maintain decent relations with the administration and not to fall for the provocations that staff routinely stage.