The new Syrian authorities have arrested military judge Mohammed Kanjo Hassan, who issued death sentences to prisoners of the Sednaya prison complex. Under Bashar al-Assad's regime, Sednaya was a site of relentless torture and executions. Its victims were protesters, military personnel, alleged terrorists, and citizens arrested for spreading so-called “fake news.” The prison’s inner workings were extensively documented: floor plans, corpse storage locations, execution schedules, and torture methods were largely known years ago. Survivors' testimonies resulted in detailed reports and even a 3D model of Sednaya. Yet the international community largely ignored this information until after Assad's regime had fallen.

Content

The non-secret prison

Anatomy of a “human slaughterhouse”

A conveyor of cruelty

Prisoners and guards

Twenty methods of torture and random executions

International indifference

“The first person I witnessed die was Khalil Alloush from Daraa, a lieutenant colonel with a strong, athletic build. One day, the prison guards entered our cell, and he dared to speak to them. They beat him brutally, fracturing his shoulder and arm. The next morning, they took him to a hospital, where they repeatedly struck his kidneys before returning him in a much worse state. Two or three days later, he succumbed to his injuries,” recounts Mutasem Abdul Sater, a former detainee of Sednaya — perhaps the most notorious prison run by Bashar al-Assad's recently deposed regime.

Sater’s is just one of hundreds of testimonies published by ADMSP (the Association of Former Sednaya Prisoners and Forcibly Disappeared Persons). The association has released several extensive reports documenting the inner workings of the prison. The site dealt both with officially sentenced prisoners and with abducted suspects, who were subjected to torture and coerced into giving forced statements by the regime’s intelligence services.

37.9% of respondents were charged with this offence

24.2% of respondents

12.1% of respondents

63.8% of respondents

57.3% of respondents

The founder of the Association of Former Prisoners and Forcibly Disappeared Persons of Sednaya, Riyad Avlar

Riyad Avlar, a Turkish citizen and the founder of ADMSP, played a pivotal role in documenting the atrocities committed in Sednaya. In 1996, as a 19-year-old student, he was imprisoned there after being arrested for writing a letter in which he described the repressions under Syria’s then-dictator Hafez al-Assad, Bashar’s father. Avlar spent 21 years in Sednaya. Upon his release, he dedicated himself to gathering information about those who had been killed or went missing in the prison. He and his colleagues interviewed former detainees, collected the names of their cellmates, and cross-referenced these with lists of missing Syrians provided by families looking for their loved ones.

Human rights activists have amassed thousands of accounts detailing deaths caused by the repressive Bashar al-Assad regime. According to ADMSP, from 2011 to 2020, 37,000 people entered Sednaya — only around 7,000 are known to have survived. Many simply remain unaccounted for. Statistics from the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) indicate that 96,321 people, including 5,742 women and 2,329 children, are still officially listed as missing after being arrested by Syrian authorities.

37.9% of respondents were charged with this offence

24.2% of respondents

12.1% of respondents

63.8% of respondents

57.3% of respondents

From 2011 to 2020, 37,000 people were held in Sednaya, of whom only about 7,000 survived

The non-secret prison

Following the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, Sednaya became a subject of global attention. Numerous articles, TV reports, and podcasts told the story of the facility and its detainees. Social media shared photos and videos of a massive press allegedly used for executions or disposing of bodies. There were also reports of secret underground levels in the prison. However, Fadel Abdulghany, Executive Director of the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), told The Insider that while these particular claims appear to be fabrications, the suspected death toll is all too real:

“The equipment in question was part of a carpentry workshop within the facility. Despite speculation, there are no confirmed underground floors in Sednaya. The prison's maximum capacity was approximately 11,000 detainees, yet only 1,600 to 2,000 were released. The remainder were systematically executed by Assad’s sadistic regime in collaboration with Vladimir Putin.”

37.9% of respondents were charged with this offence

24.2% of respondents

12.1% of respondents

63.8% of respondents

57.3% of respondents

Human rights activists were aware of the atrocities in Sednaya well before the fall of the Syrian regime. The first source of information about the abuse of prisoners came from the testimony of a military photographer who fled the country and is referred to in reports by the pseudonym “Caesar.” He documented the bodies of those executed or tortured to death in Sednaya and the Tishreen military hospital, where the bodies of deceased prisoners were transported.

“Caesar” provided 28,707 photographs of dead bodies, from which 6,786 people were identified. Human Rights Watch published a report based on this material as early as December 2015.

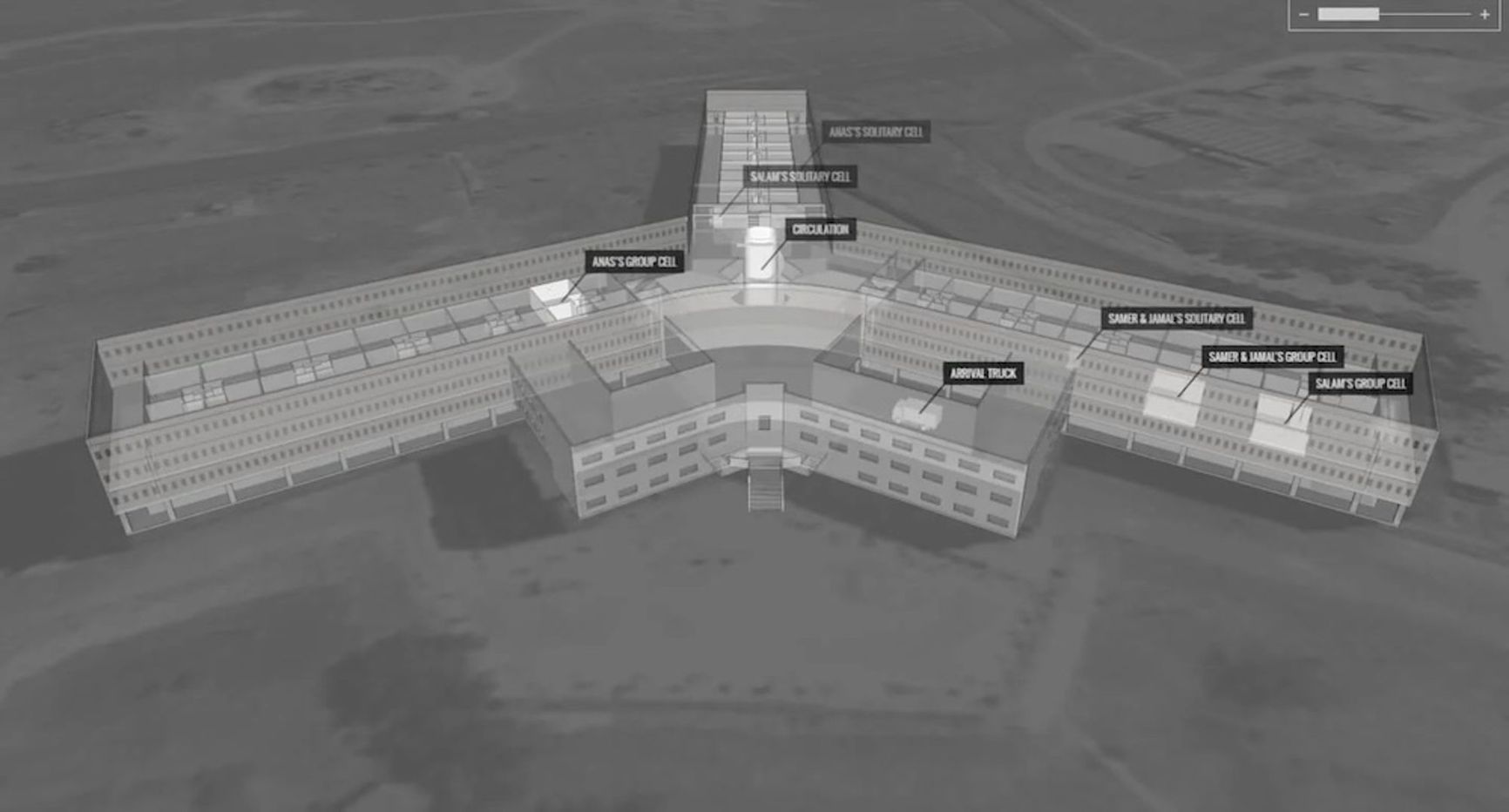

In 2016, the British research organization Forensic Architecture, in collaboration with Amnesty International, launched the Explore Saydnaya project — a website featuring a 3D model of Sednaya and recorded testimonies of its prisoners. At the time, no images of the prison were publicly available, so the model was created based on accounts from surviving detainees. It was within the Explore Saydnaya project that the prison was first described as a “human slaughterhouse.”

37.9% of respondents were charged with this offence

24.2% of respondents

12.1% of respondents

63.8% of respondents

57.3% of respondents

Explore Saydnaya project's 3D model of Sednaya

The founder of Forensic Architecture, Eyal Weizman, explained to The Guardian that the project was intended as a political tool:

“Our goal is to ensure this place is shut down and to prevent any peace agreements from being made with Assad.”

Anatomy of a “human slaughterhouse”

The land on which Sednaya prison stands was confiscated from local residents in 1978. Construction lasted from 1981 to 1986, with the first prisoners arriving that same year. Unlike other Syrian prisons, which are managed by the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Sednaya was under military control. The Ministry of Justice had no oversight of its operations, and representatives from the Red Crescent and human rights organizations were not allowed inside, according to an ADMSP report on the prison’s internal structure.

The prison complex is located 30 kilometers from Damascus and spans 1.4 square kilometers. It consists of two main buildings: the “Red Building,” with three wings, and the more modern “White Building.” Initially, the White Building was intended for prisoners from the military, while the Red Building housed civilians convicted by military field courts. After the protests of 2011, the White Building began to hold officially sentenced prisoners, while the Red Building was used for detainees held without trial “for security reasons.” Convicts were beaten and tortured as punishment for perceived infractions, and detainees were subjected to constant and arbitrary abuse.

37.9% of respondents were charged with this offence

24.2% of respondents

12.1% of respondents

63.8% of respondents

57.3% of respondents

Sednaya Prison after the release of prisoners, December 9, 2024

Both buildings in Sednaya prison were equipped with special rooms for executions, which were primarily carried out by hanging. The bodies of those executed were taken directly to cemeteries, while the corpses of those who died from torture, beatings, or starvation were initially stored in so-called “salt rooms.” These rooms had floors covered with a 20-30 cm layer of salt to prevent the bodies from decomposing. In 2011, two such rooms were set up in the Red Building. “At that point, Sednaya effectively became a death camp,” notes the ADMSP report.

37.9% of respondents were charged with this offence

24.2% of respondents

12.1% of respondents

63.8% of respondents

57.3% of respondents

The corpses of those who died from torture were initially stored in so-called “salt rooms.” These rooms had floors covered with a 20-30 cm layer of salt to prevent the bodies from decomposing

The bodies stored in the salt rooms were later transported in trucks to the Tishreen military hospital, where staff examined them and documented the deaths.

Sednaya prison was guarded by 200 soldiers and 250 military police officers. The complex was surrounded by two layers of minefields, including anti-tank and anti-personnel mines. The prison garrison was equipped with six T-80 tanks, eight infantry fighting vehicles, and various RPGs, machine guns, and automatic grenade launchers.

A conveyor of cruelty

Prisoners were brought to Sednaya in trucks with sealed metal compartments resembling those of refrigerated vehicles used for transporting animal carcasses. The trucks were grimly nicknamed “meat wagons.” Inside, a long metal chain ran through the compartment, and detainees were shackled to it by their wrists. Upon arrival at the prison, guards entered the trucks and threw the prisoners out “like sacks of onions,” as one survivor described. The detainees were then forced to strip naked, lie face down on the ground, and were savagely beaten.

37.9% of respondents were charged with this offence

24.2% of respondents

12.1% of respondents

63.8% of respondents

57.3% of respondents

A torture victim in one of the Syrian prisons

Such beatings lasted for hours and often resulted in the deaths of prisoners. According to one witness who spoke to human rights activists, out of their group of 100 detainees, 15 did not survive this “intake process.”

In their first days at the prison, detainees were kept in overcrowded quarantine cells. One survivor recounted sharing a 3x4 meter room with 29 other people, while another described a 2x2 meter cell crammed with nine inmates. Newly arrived prisoners were fed meager portions: a daily ration consisted of two spoonfuls of rice or bulgur wheat, half a loaf of bread, and half an olive.

Later, prisoners were moved to larger cells — measuring 5x7 meters — which housed up to 40 people. While food improved slightly, it was often used as a tool of humiliation. Guards would throw meals on the floor or even into toilets, forcing starving inmates to eat from these unsanitary places.

Water supply issues were a recurring problem in the prison. On such days, even in extreme heat, prisoners were given just one liter of water. Former inmates recalled that a single glass of water could be traded for two loaves of bread.

Prisoners were allowed to shower once every two or three months. On the way to and from the showers, they were beaten. “We always came back from the shower with wounds,” one survivor recalled.

Inmates were forbidden from looking at the guards. When a guard entered the cell, prisoners were required to turn toward the wall. If they were ordered to move somewhere, they had to tightly cover their eyes with their hands or pull a shirt over their head. Any prisoner caught looking at a guard risked having their eyes gouged out as punishment.

37.9% of respondents were charged with this offence

24.2% of respondents

12.1% of respondents

63.8% of respondents

57.3% of respondents

Inmates were forbidden from looking at the guards. Any prisoner caught looking at a guard risked having their eyes gouged out as punishment

According to survivors, many prisoners would send messages through released cellmates asking their loved ones not to visit them. This was because they were subjected to beatings both before and after meetings, which could sometimes result in death.

For example, Nayef Faisal al-Rifai, a former military judge with the rank of captain, met his end this way. After a visit from his wife, one of the guards struck him in the abdomen with an iron pipe. This caused internal bleeding, and he died three days later. “I loved al-Rifai because he was an optimist. He always said, 'We will be free and rid of this criminal,' referring to Bashar al-Assad,” recounted Lieutenant Khaldoun Mansour, a former cellmate of the judge who had been arrested for refusing to fire on protesters.

The wife of another prisoner described her experience of visiting the prison:

“There were prisoners from almost every province in Syria. Some had bloodied faces; others had to be carried into the visitation area on stretchers. I learned that inmates in Sednaya were beaten before and after visits, so they begged their families never to come again. We had heard rumors about this, but I didn’t believe them until I saw it with my own eyes.”

Prisoners and guards

In 2019, ADMSP interviewed more than 400 former Sednaya prisoners to determine who was sent to the prison and for what reasons. The length of imprisonment among participants ranged from two years to 21 years. About one-third of the detainees were held longer than their sentences required.

The most common charges were participation in banned organizations, “weakening national morale” or inciting discord and spreading “fake news” to that end, and “knowingly disseminating false or exaggerated news that undermined the state's prestige or financial standing” from abroad. Only 8% of respondents were imprisoned for terrorism or attempts to commit such acts.

Among the respondents, 2% were minors at the time of their arrest, and more than 63% held university degrees or other advanced academic qualifications.

37.9% of respondents were charged with this offence

24.2% of respondents

12.1% of respondents

63.8% of respondents

57.3% of respondents

One of the cells in Sednaya after the release of prisoners

More than half of the study participants reported that their relatives paid bribes in exchange for promises of release. These were significant sums by Syrian standards — over $4,000 in each case. Respondents also noted that their families paid bribes of $1,500 or more to obtain information about imprisoned relatives or to arrange visits with them.

One former Sednaya prisoner, Mohammad Abdulsalam, told the BBC in 2023 that he was indeed released after a bribe was paid. He had been arrested for participating in protests in Idlib, and his father sold his land and paid over $40,000 to secure his son's freedom. Before his release, Mohammad had spent five years in the prison.

Other former inmates said that paying bribes had helped them avoid execution. All of them had been sentenced to hanging, but their families reportedly paid Sednaya guards tens of thousands of dollars per person. According to Riyad Avlar’s estimates, between 2011 and 2020, the prison guards likely received around $900 million in bribes.

37.9% of respondents were charged with this offence

24.2% of respondents

12.1% of respondents

63.8% of respondents

57.3% of respondents

According to human rights activists' estimates, the prison guards likely received around $900 million in bribes between 2011 and 2020

The prison guards were mostly uneducated young men aged 18–20. “They harbor deep hatred toward university graduates, public figures, the wealthy, and the elderly,” states the ADMSP report. Detained doctors, lawyers, officers, and journalists faced harsher treatment in Sednaya than similar categories of inmates did in other prisoners.

Twenty methods of torture and random executions

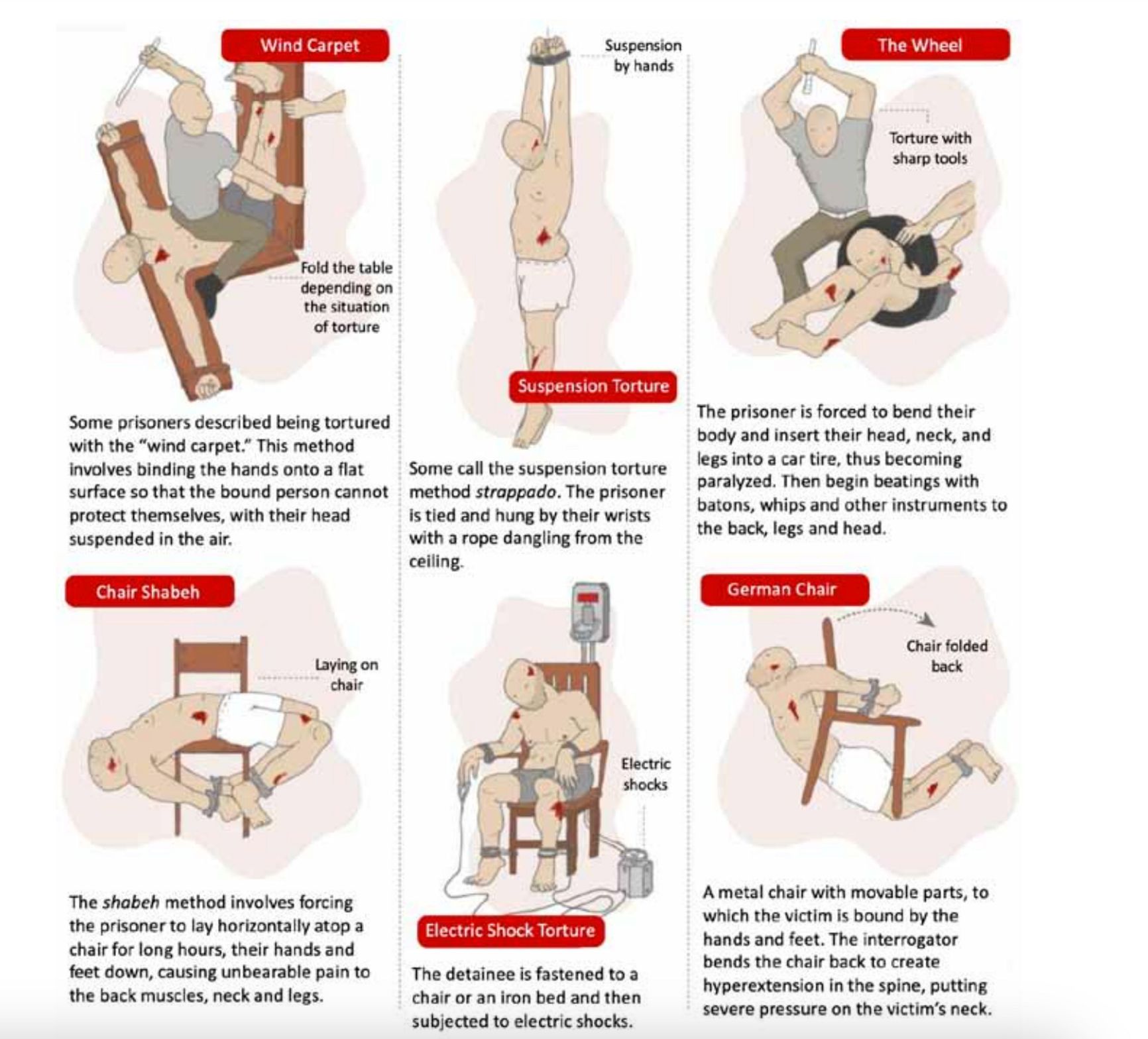

A detailed report has also been compiled on torture in Sednaya. Nearly all inmates were subjected to physical and psychological abuse. Accounts of sexual violence were reported by 29.7% of respondents, though this figure may be artificially low due to the sensitivity of the topic and a reluctance to speak openly about it.

37.9% of respondents were charged with this offence

24.2% of respondents

12.1% of respondents

63.8% of respondents

57.3% of respondents

The most common types of torture in Sednaya prison. Illustration from the ADMSP report.

The ADMSP classified 20 main types of torture and created a ranking of their “popularity” among the prison guards. The most common form was beating with sticks, followed by whipping. The third most common was the so-called “wheel,” in which the prisoner is seated in a way that their head and legs are fixed inside a car tire, and they are beaten with sticks and whips. 80% of the former prisoners who were surveyed reported experiencing this form of torture. Nearly 70% faced a staged execution.

The majority of survivors were also starved, trampled, and doused with cold water. Many were tortured with electricity, suspended from the ceiling, and tied up for beatings. Tank engine drive belts were used for beatings, as they completely tear off the skin at the point of impact. Iron pipes, brass four-wire cables, PVC plumbing pipes, and silicone rods intended for plastic welding were also used.

“In the security services, torture is mainly used to obtain information or confessions. If it is punishment, it continues until the detainee screams from pain, because silence is considered a challenge to the torturers. In Sednaya, it's the opposite: during beatings, you must remain silent. If you scream, the beating will intensify,” explained one of the prisoners.

37.9% of respondents were charged with this offence

24.2% of respondents

12.1% of respondents

63.8% of respondents

57.3% of respondents

“In Sednaya, you must remain silent during beatings. If you scream, the beating will intensify”

The most common form of sexual torture was damage to the genitals. Almost 9% of those who reported such abuse faced the threat of sexual violence, and 3% said they were subjected to rape with foreign objects.

With Bashar al-Assad coming to power in 2000, Sednaya guards began to use torture more frequently, leaving marks on visible parts of the body via branding, scalding with boiling water, and skin removal. Sexualized torture became much more widespread after 2011.

At that time, extrajudicial executions also began in the prison. Soldiers would enter the cells and randomly kill prisoners. According to Riyad Alvar, the peak of such executions occurred in 2013 and 2014.

Sednaya became a symbol of repression, playing a central role in suppressing opposition during the Syrian Civil War, explains SNHR director Fadel Abdulghany:

“The cruelty was not random, but served calculated and oppressive objectives. The severity of brutality inflicted served as a chilling deterrent to the broader population and sent a clear message: opposing the regime results in unthinkable suffering. Practices such as torture, starvation, and mass executions were systematically employed to obliterate dissent and dismantle organized resistance against the regime.”

International indifference

Despite the efforts of human rights defenders, until December 2024, the name Sednaya had been mentioned by only around 70 English-language publications — and half of the mentions were on the website of the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, another group that collects testimonies about those killed in the prison.

37.9% of respondents were charged with this offence

24.2% of respondents

12.1% of respondents

63.8% of respondents

57.3% of respondents

Explaining the international community's indifference to what was happening in Sednaya, Fadel Abdulghany points to several factors. One of them was secrecy: “The Assad regime implemented stringent secrecy around Saydnaya’s operations. Executions were conducted covertly, often at night, with layers of compartmentalization preventing even prison staff from fully understanding the scale of abuse.”

Since 2011, Assad's regime has not allowed international observers into its prisons. As a result, human rights defenders could only rely on eyewitness accounts and indirect evidence. “The lack of visual evidence from Sednaya made it difficult to attract media attention,” notes Abdulghany.

In the human rights defender's view, there is also a purely psychological component. The extreme nature of human rights violations in Sednaya — systematic torture, sexualized violence, and mass executions — provoked “distrust and insensitivity from the global audience,” he says. Former prisoners themselves were often unwilling to talk about their experiences due to severe trauma and fear of retribution from the regime.

Another reason the atrocities of the Syrian regime were overlooked was the support of allies like Russia, which used its UN Security Council veto to shield Assad from accountability on a global level. The scale of the tragedy also played a role With the Syrian refugee crisis and the rise of groups like ISIS attracting so much attention internationally, even major Western news outlets treated issues like human rights and regime repression into the background.

Amnesty International directly accused Russia of complicity in the events. “For many years, Russia used its veto power in the UN Security Council to protect its ally, the Syrian government, and prevent individual perpetrators within the government and armed forces from facing trial for war crimes and crimes against humanity,” said Amnesty International representative Philip Luther in an interview with The Guardian.

37.9% of respondents were charged with this offence

24.2% of respondents

12.1% of respondents

63.8% of respondents

57.3% of respondents

Bashar al-Assad and Vladimir Putin

Fadel Abdulghany is convinced that the Russian authorities could not have been unaware of the torture in Sednaya and deliberately restricted access to information about it:

“Russia bears moral and legal responsibility for its role in these atrocities. It must provide compensation to the victims, issue an unequivocal apology, and take concrete steps to rebuild trust and open a new chapter with the Syrian people.”

37.9% of respondents were charged with this offence

24.2% of respondents

12.1% of respondents

63.8% of respondents

57.3% of respondents