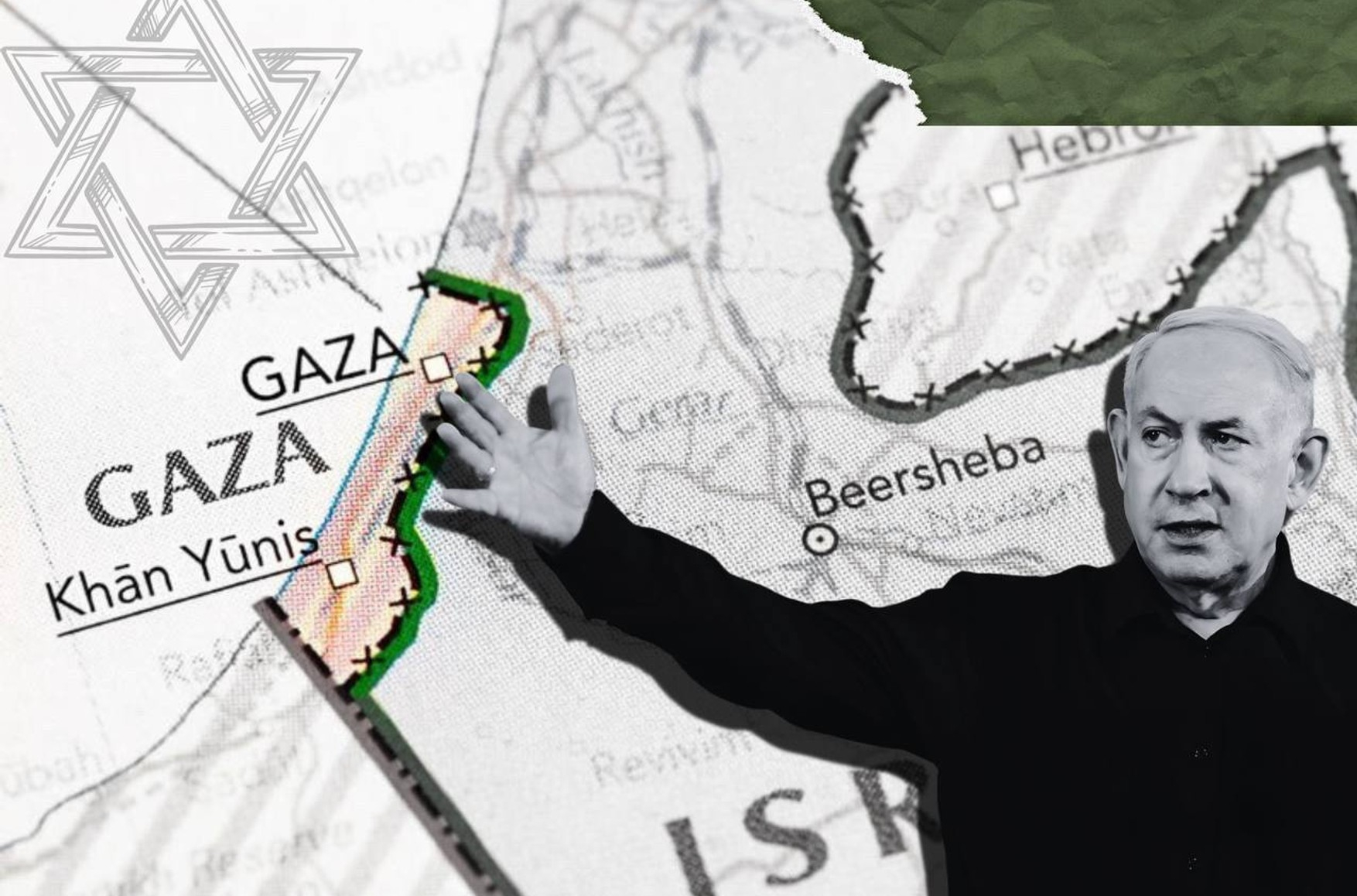

In a recent development, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has openly opposed the idea of granting control over the Gaza Strip to the Palestinian Authority. This stance suggests that Israel is contemplating taking direct control of Gaza, essentially signaling an occupation. International agreements dictate that the Gaza Strip should remain outside the boundaries of the Jewish state. If Netanyahu's plan comes to fruition, it would mark the third instance of Gaza being occupied since the establishment of modern Israel. However, characterizing this move as a return to the “one-state solution” model may not be accurate. It appears that Israelis themselves are hesitant about fully integrating Gaza, including the potential distribution of Israeli passports.

Content

The end of the annexation era

The right to occupation

Not much good in the Gaza Strip

Triumphant six-day war

Status: It's complicated

The future of Gaza

The end of the annexation era

With the conclusion of the Second World War, the era of annexations – the incorporation of one state (or its parts) into another without the consent of the annexed state – effectively came to an end.

Over the past 80 years, the majority of territories annexed during this period have returned to their rightful owners. Indonesia was compelled to acknowledge the independence of the occupied East Timor, Eritrea fought for thirty years against Ethiopian forces that had seized it and ultimately emerged victorious, and Iraq was expelled from Kuwait.

The number of successful annexations after the Second World War can be counted almost on one's fingers. India, soon after gaining independence from the British Empire, forcefully assimilated the Portuguese colony of Goa and several principalities claiming their own sovereignty. In 1950, China captured Tibet and formally incorporated it into its territory. Communist North Vietnam annexed South Vietnam in 1975. Essentially, these are all the annexations that states-aggressors managed to carry out and that were accepted by the global community. However, there are annexations that were formally successful but not recognized by the international community, and almost all of them were carried out by Israel.

The number of successful annexations after the Second World War can be counted almost on one's fingers

In 1967, Israelis seized and, in 1980, officially incorporated East Jerusalem into their territory, which, according to international law, is designated as part of Palestinian territories. In 1981, the Syrian Golan Heights, control of which Damascus lost in the same year of 1967, also formally became part of Israel.

From the late 1960s to the present day, the construction of Israeli settlements has continued on Palestinian lands in the West Bank. De jure, these settlements are not part of Israel, but Israeli laws apply there, and the residents of these settlements are protected by the Israeli army. The only thing lacking for complete annexation is the formal recognition by the Israeli parliament of Israel's sovereignty over them. Netanyahu's team has long prepared a corresponding bill, using it for years to intimidate Palestinians and court right-wing Israeli voters.

The UN Security Council votes every few years on a resolution condemning annexations, and Israelis routinely ignore these resolutions. Moreover, in 2019, they managed to persuade U.S. President Trump to recognize the annexation of the Golan Heights. Apart from the U.S., only Micronesia—an island state in Oceania with a population of just over a hundred thousand—recognizes their belonging to Israel. The rest of the world considers the Golan Heights as Syrian territory.

In essence, Israel has been living for decades within borders unrecognized by the UN and other international organizations, openly preparing to expand these boundaries. However, Israelis claim that the UN is deceptive: the League of Nations, the predecessor of this organization, confirmed in the early 20th century that Jews have the right to “reconstitute their national home” in the territory then administered by the British, known as Palestine. The specific borders of this “national home” were not delineated, the League of Nations' decision was not formally revoked by the UN, giving many in Israel grounds to believe that the entire former mandate of Palestine should be part of the Jewish state.

The right to occupation

Israeli annexations and occupations rest on two primary justifications: religious and military. The religious argument is grounded in the conviction that the Jewish state should be restored within its historical boundaries, encompassing all the lands mentioned in the Bible as designated for the Jewish people. Among these lands are the Palestinian territories of the West Bank, officially termed Judea and Samaria in Israel. The majority of the hundreds of thousands of Jewish settlers there are devout adherents, ready to endure constant threats from Arab neighbors and practical inconveniences, such as residing in makeshift homes without water and electricity, in pursuit of fulfilling an age-old biblical mandate.

Jewish West Bank settlers are ready to endure constant threats from Arab neighbors in pursuit of fulfilling an age-old biblical mandate

From a military perspective, the presence, notably on the Golan Heights, is deemed imperative to ensure Israel's security. As the name suggests, this territory is an elevated position from which artillery or missile fire could potentially reach almost the entire northern region of the Jewish state. The necessity to shield Israeli cities from hostile shelling by Syria initially led to occupation and later to the annexation of the Golan Heights.

Golan Heights

RIA Novosti

At times, military considerations clash with religious beliefs. Such a conflict arose, for instance, in the Gaza Strip in the early 2000s. Several thousand Jewish settlers in the region found themselves virtually surrounded on all sides by predominantly unfriendly Arab populations. Ensuring the safety of these settlements became increasingly challenging for Israel, and in 2005, Prime Minister Ariel Sharon's government simply evacuated (often forcibly) all settlers from the Gaza Strip.

“This disengagement will strengthen Israel's control over the territory necessary for our existence (...) It will reduce hostility (...) and bring us closer to peace with the Palestinians,” Sharon said, justifying the need to dismantle the settlements.

In the current Jewish press, the decision of the long-deceased politician is often termed a “stab in the back” to Israel, openly asserting that without this unilateral disengagement, the tragedies of October 7th would likely not have occurred..

Not much good in the Gaza Strip

In the prelude to the creation of Israel, the partition plan for the British Mandate of Palestine allocated approximately twice the territory to the Palestinian region around the city of Gaza than it currently occupies. However, Arab leaders at the time—in 1948—rejected this plan and sought to prevent the establishment of a Jewish state, ultimately turning the Gaza Strip into a small enclave cut off from the rest of Palestinian territories.

During the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, the Gaza Strip was occupied by the army of neighboring Egypt. They couldn't advance further, and eventually, a ceasefire was signed between them and the Israelis, with Egypt retaining control over the occupied territory. This territory, slightly adjusted in its borders two years later, became what is now known as the Gaza Strip.

Cairo never declared plans to annex Gaza, despite its military and administrative presence there. However, Israelis did make such declarations. In 1949, Israel officially informed the UN of its intention to incorporate Gaza and its surroundings. Israelis were willing to recognize all residents of the region, including tens of thousands of Arab refugees from other parts of the former British Mandate of Palestine, as citizens of their state. However, there was one condition: the UN had to financially assist in integrating these people into the newly established Jewish state. Egypt vehemently opposed this idea, and thus, the Israeli annexation of Gaza never materialized.

As a result, the Gaza Strip found itself in a very peculiar legal situation: the Palestinian Arab state, of which it was supposed to be a part, never materialized; Israel was prevented from incorporating the region, and the Egyptian authorities controlling the sector did not want to see it as part of their country. By the way, then as now, Cairo refused to accept refugees from Gaza, and many Palestinians who managed to enter Egypt were soon deported.

For Egypt, the residents of Gaza were too impoverished, poorly educated, radical, and numerous to become their fellow citizens. Allowing them to become part of Israeli society was also prohibited by the pan-Arab ideology promoted by then-Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, which had no room for a separate Jewish state in the Middle East.

Egyptians used Gaza as a base for preparing provocations and attacks on their hostile neighbor, Israel. In response, Israelis conducted retaliatory actions in the Gaza Strip (one of the bloodiest, where about forty people died, was commanded by Ariel Sharon, who would later evacuate all Israelis from the Gaza Strip). In 1955, former Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, who then held the position of Defense Minister, proposed a radical solution to the Gaza problem: forcibly drive out the Egyptians and occupy the city along with all its surroundings. His cabinet colleagues did not support this decision. However, soon after, the Israeli army occupied the Gaza Strip anyway.

Egyptians used Gaza as a base for preparing provocations and attacks on their hostile neighbor, Israel

In 1956, France and Britain initiated an invasion of Egypt. This occurred after President Nasser declared the nationalization of the Suez Canal—a critically vital part of the main maritime route connecting Asia to Europe. European powers, who had financed the construction of the canal and controlled ship traffic through it, viewed Nasser's decision as a threat to their economic and military security and decided to regain control by force.

Egyptian armies near the Suez Canal and on the Sinai Peninsula, separating it from the Gaza Strip, were defeated. Several thousand Egyptian soldiers in Gaza found themselves cut off from their main forces, and Israel seized the moment to try to address its issues with Gaza. By that time, numerous Arab resistance groups were operating in the region, launching attacks against Israelis and organizing acts of terrorism.

With the tacit support of the Egyptian administration, Palestinian militants (referred to as fedayeen, meaning “those who sacrifice themselves for the faith”) established entire camps in the Gaza Strip to train new fighters. The destruction of these camps and the arrest of militants became the justification for the invasion of the Gaza Strip and the establishment of Israeli administration there. In Gaza, this period is referred to as the “First Occupation.”

Incidentally, the rest of the world also perceived Israel's rule in Gaza at that time as an occupation, i.e., as a forcible and unlawful takeover of territory. U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower, after the French and British armies withdrew from Egypt under pressure from the U.S. and the USSR, wrote an angry letter to the Israeli cabinet demanding the withdrawal of troops from Gaza. Eventually, the Israelis complied, exited Gaza, and handed control of the region to UN peacekeepers. The Israeli military-administrative presence in the Gaza Strip then lasted only a few months.

On December 3, 1956, the Israeli pound was declared the official currency of the region, marking the beginning of Israeli rule. On March 7, 1957, the Israeli army left Gaza. During its presence in the region, approximately a thousand Palestinians were killed or went missing. The majority of them died in raids against the fedayeen.

During its presence in the region, approximately a thousand Palestinians were killed or went missing

The UN administration also did not last long in Gaza. From the very beginning of their presence, peacekeepers faced mass protests by Palestinians demanding a return to Egyptian rule. After Nasser gave assurances of demilitarizing Gaza and eliminating the remaining fedayeen, control over the rebellious region was returned to him.

The Egyptian president kept his promises in a somewhat peculiar manner. While military units were indeed withdrawn from the Gaza Strip, many fedayeen simply changed their status from illegal underground operatives to legal representatives of the Palestinian militia, tasked with maintaining public order. Although many underground operatives were indeed expelled and found refuge in Syria, Jordan, and other Middle Eastern states.

The immense popularity of Gamal Abdel Nasser among Gaza's residents almost led to the complete fading of aspirations for Palestinian independence in the region. In order to rekindle these aspirations, dedicated efforts were undertaken by representatives of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), founded in 1959, among whom was Mahmoud Abbas, the current Palestinian President. Serving as one of the key figures for the PLO in Gaza during the early 1960s, Abbas made frequent visits to the Gaza Strip, using fictitious pretexts.

Through his efforts and the efforts of rulers of several Arab states dissatisfied with Egypt's constant presence in what they believed should be part of an independent Palestinian state, the political beliefs of Gaza's residents gradually, but noticeably, changed. By the mid-1960s, the sentiments had shifted to such an extent that in 1965, Nasser found himself compelled to formally acknowledge the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) as the legitimate representative of the Palestinian people. It is conceivable that even during this period, he perceived the PLO as prospective allies in the impending conflict against Israel—a topic about which the Egyptian president frequently expounded.

Triumphant six-day war

The war began at the dawn of June 5, 1967, with a preemptive strike by the Israelis on military airfields and troop positions of neighboring Arab states that were amassing forces to attack Israel. It was anticipated that Arab armies would annihilate the Jewish state with a single decisive blow. However, things did not unfold as expected. In just six days, Israel defeated all its adversaries and not only avoided destruction but significantly expanded the territories under its control.

For instance, Jordanian forces were expelled from East Jerusalem and the West Bank of the Jordan River. Egypt not only relinquished the Gaza Strip but also the entire adjacent Sinai Peninsula. It was quite logical to term the reinstatement of Israeli military and administrative presence in Gaza as the “Second Occupation.” An occupation that many residents of the strip were not willing to accept.

Fedayeen and former fighters of the Egyptian militia, who joined them, seized the arsenals left by fleeing Nasserite forces, including mortars and anti-tank mines. They managed to mount a real resistance against the well-prepared and victorious Israeli army. Due to the activities of militants and the resistance of the local population, the process of establishing full control over the entire Gaza Strip stretched out for four years. These were four years not only of military and police operations but also of attempts to integrate some of the sector's residents into the Israeli economy, as well as deportations to Jordan and Sinai, and propaganda efforts aimed at convincing local residents of the necessity to collaborate with Israelis.

However, all this did not yield quick results, and in 1971, Ariel Sharon, the commander of Israeli forces in Gaza (yes, the same one), proposed his plan for the integration of the Gaza Strip. It envisaged the complete elimination of refugee camps, which Fedayeen had been using as bases, with the resettlement of their inhabitants to Sinai or their dispatch to Jordan. Additionally, it proposed the establishment of Jewish settlements near Gaza. The political leadership of Israel did not endorse this plan; Sharon was soon dismissed, but the settlers did indeed head towards the Gaza Strip. By the end of 1972, there were already about 700 people in the region. A few hundred more lived in settlements in Sinai. However, their stay there was not long-lasting.

In 1973, Anwar Sadat, who had replaced the deceased Nasser as the President of Egypt a couple of years earlier, attempted to forcefully reclaim Sinai during the Yom Kippur War. However, Egypt and its supporter, Syria, once again suffered defeat.

In 1979, Sadat became the first Arab leader to recognize Israel's right to exist and established diplomatic relations with the Jewish state. In exchange for peace with Egypt, Israel relinquished Sinai. However, the Gaza Strip remained under Israeli control. For many years, rumors circulated that Israelis were making every effort to transfer Gaza to Sadat, and he vehemently resisted, but these rumors are not confirmed by participants in the negotiations from either side.

In 1979, Sadat became the first Arab leader to recognize Israel's right to exist and established diplomatic relations with the Jewish state

Status: It's complicated

The status of the Gaza Strip (along with the other Palestinian territory, the West Bank of the Jordan River) remained highly uncertain for years. Israel did not recognize it as part of the Palestinian state because it had not yet agreed to the existence of such a state. The Gaza Strip was not incorporated into Israel, yet it operated with a dual administration. There was a local Arab administration handling municipal matters like waste disposal and street lighting, while a military Israeli administration was responsible for everything else.

Israel exercised strict control over the political, economic, and even religious life of Gaza. Activists advocating resistance to Israeli presence were arrested, and in response to Palestinian attacks, Israelis carried out retaliatory actions. Meanwhile, the number of settlers in the Gaza Strip increased, viewed by Arabs as occupiers. The situation within the region became increasingly complex and dangerous, with terrorist acts and subsequent retaliatory actions becoming more and more brutal. In 2000, it escalated into a new intifada, a widespread uprising that engulfed all Palestinian territories.

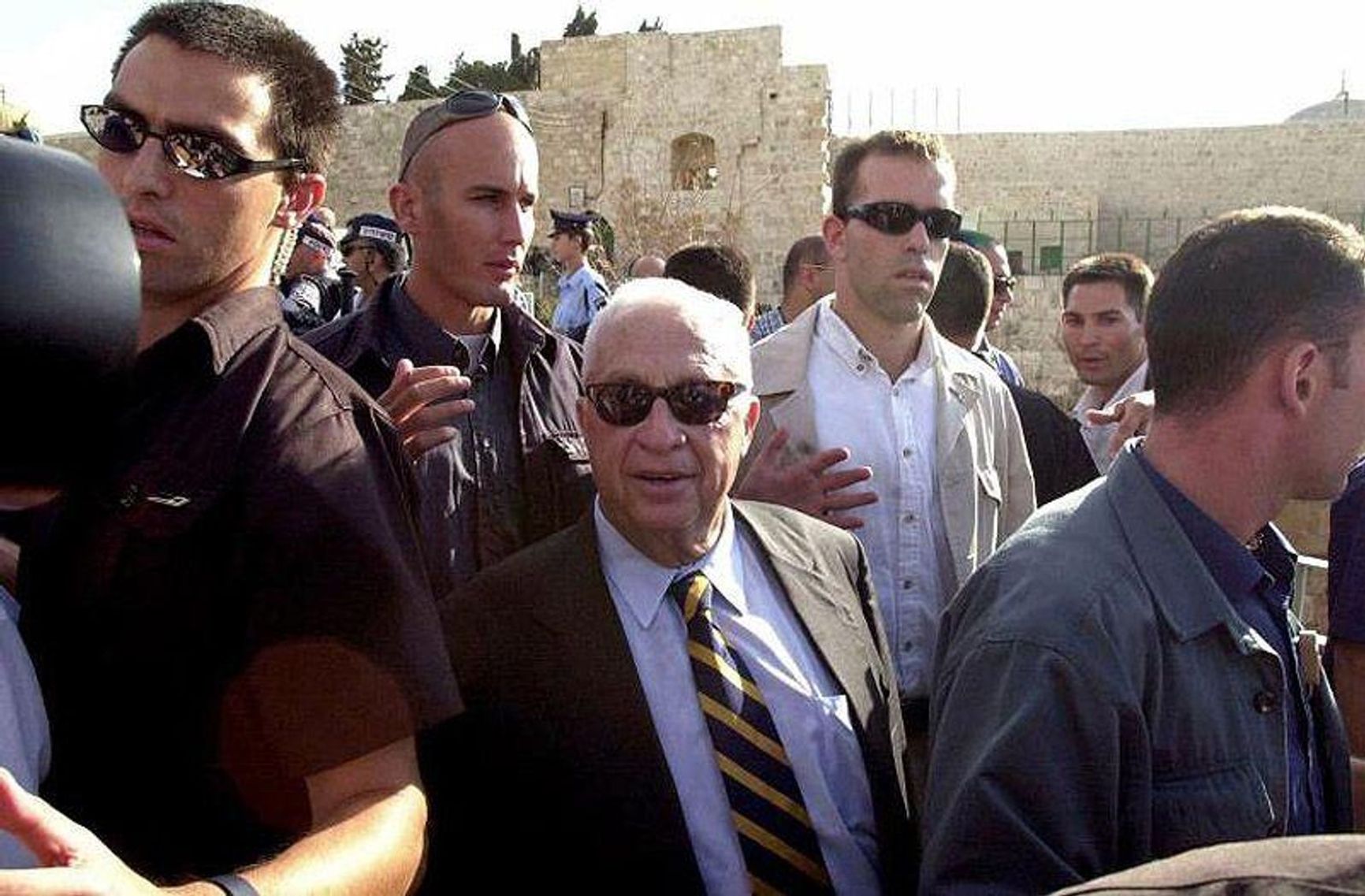

As you might expect, Ariel Sharon played a role in those events as well. Having long transitioned from a military career to politics, the leader of the Likud parliamentary party, Ariel Sharon, ascended the Temple Mount in Jerusalem in the fall of 2000. The site had housed the main Jewish shrine, the Jerusalem Temple, until its destruction by the Romans at the beginning of the new era.

Ariel Sharon on the Temple Mount

After the Islamic conquest of the Holy Land, the Al-Aqsa Mosque was built on the ruins of the temple, along with the Dome of the Rock pavilion erected around the stone from which, according to Muslim belief, Prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven. The presence of an individual, who had overseen retaliatory operations and deportations, near such important Muslim sanctuaries was perceived by Palestinians as an unforgivable sacrilege. A wave of attacks and assaults on military and police personnel swept across Israel. The uprising persisted for several years, claiming the lives of over a thousand Israelis and around five thousand Palestinians.

This intifada became the reason for the resumption of Israeli control over the West Bank of the Jordan River—a territory where, before the uprising, administrative functions were gradually being transferred from the Israeli administration to local self-government bodies. Israelis believed that Palestinian officials had failed to ensure security, leading to a significant reduction in their authority. Conversely, in the Gaza Strip, it was decided to leave everything under Palestinian control.

According to the plan of Ariel Sharon, who led the Israeli government in 2001, not only were all settlers to be evacuated from Gaza, but all troops were also to be withdrawn. As mentioned earlier, he believed that this decision would bring the onset of peace between Arabs and Jews. By the end of the summer of 2005, all 8,000 settlers had left the Gaza Strip. In September, the military withdrew from the region.

The episode in history known in Gaza as the “Second Occupation” was permanently concluded. While Israeli forces returned to Gaza after 2005 several times to eliminate militant leaders or conduct operations against Hamas, they never stayed and left once their objectives were achieved. However, now they have come to stay.

The future of Gaza

Following Israel's military operation in the Gaza Strip that commenced on October 7th of this year in response to a bloody incursion by Hamas, the question arose: what to do with Gaza after the operation concludes? American partners of Israel proposed handing over control of the Gaza Strip to the Palestinian Authority. In other words, applying the same practices as those in effect on the West Bank: Palestinian officials would be responsible for culture, tourism, and landscaping, while Israelis would handle everything else, with the Israeli army and security services maintaining a constant presence in the region.

However, neither Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas, who stated that he does not want to be a figurehead ruler under what is essentially an occupying administration, nor Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who refuses to entertain the idea of Palestinian self-governance in Gaza, agreed to this. According to Netanyahu, Israel will remain in Gaza “for an indefinite period” to ensure security.

From these two statements—one about the impossibility of handing power even to moderate Palestinians and the willingness to keep the army in the Gaza Strip indefinitely—one can infer that the region is on the verge of a “Third Israeli Occupation.” Israelis will assume all administrative functions, security forces will receive unprecedented powers, and the region's economy will be subordinated to the interests of Israel.

However, there is still no answer to a crucial question: will annexation follow the occupation? Will Netanyahu's government decide on the formal inclusion of the Gaza Strip into Israel? At first glance, this seems an insurmountable burden for Israel. The Gaza Strip is home to over two million people, the majority of whom are not merely disloyal but openly hostile to Israel. These individuals are ideologically, religiously, and culturally alien to Israel. Most lack the education or qualifications required in modern economic conditions.

The Gaza Strip is home to over two million people, the majority of whom are not merely disloyal but openly hostile to Israel

Granting Israeli passports to these people is unlikely to be endorsed even by the most radical government, as it would mean doubling the number of Arabs with Israeli citizenship. With Israel's population at around 10 million, at least 4 million would be Arabs with voting rights, and Israel is not morally ready for that. One only needs to look at the statements made by Israeli politicians when discussing Gaza residents. Commonplace in such statements are calls to expel them to Egypt, despite Cairo's reluctance to accept refugees. Netanyahu himself urges European partners to pressure the Egyptians to accept Palestinians.

In other words, for Gaza's integration to become politically acceptable to Israel, it would be necessary to expel Palestinians, collectively punish all residents of the region for the unleashed Hamas war, and turn millions of people into refugees (while Arab neighbors of Israel are unwilling to accept Palestinian refugees). If the humanitarian situation in the region continues to be as critical as it is now, desperation may drive people in the Gaza Strip to initiate a mass exodus, defying all prohibitions, the Egyptian authorities' reluctance to see them on their territory, and tanks stationed at the Egyptian border. Moreover, there will never be enough tanks to stop hundreds of thousands of desperate people.

If a mass exodus of Palestinians does not occur, Gaza will face another Israeli occupation, the main task of which will be to detect and eliminate all threats to the Jewish state. It could continue for years or even decades until a future Israeli prime minister decides that unilateral disengagement can bring peace to both Jews and Palestinians.