Despite Putin's assertion of a major scientific breakthrough in Russia, scientists are alarmed by the destructive impact of the war on their field. The exodus of experts from the country and the challenges faced by those who remain paint a picture of scientific work that has become increasingly difficult. Leading institutes are discontinuing joint projects due to a shortage of reagents, and not all science workers have been exempted from mobilization. There are even reports of research institutes circulating lists of materials and equipment that can no longer be imported and must be urgently sourced elsewhere, which is unrealistic given the current circumstances.

Illustrations created by Midjourney.

Content

Fleeing scientists

Dismissals and the ban on “remote work”

Loss of access to data

Shortage of reagents

Severance of international ties

“We were encouraged to steal the recipe and cook up stuff”

No exemption from mobilization

No money, no research

Fleeing scientists

Following the start of the full-scale invasion, there was a rapid increase in the number of scientists leaving Russia, which turned into an avalanche-like phenomenon with the announcement of mobilization. Those who can continue their careers abroad are taking this opportunity to leave the country. However, the main challenge they face is finding a job in their field. Fortunately, foreign colleagues are often willing to lend a helping hand and offer positions to talented Russian specialists. This was the case with Sergei, a 28-year-old molecular biologist who previously worked at a large research center in Russia. His area of expertise was drug-resistant tuberculosis, and he studied the development of mycobacteria resistance to drugs. Sergei also had several articles published in international journals.

Usually, emigration leads to a loss of status for specialists. Molecular biologist Alexander (name changed), a candidate of biological sciences and a co-author of approximately 50 publications in international scientific journals, explains that it can be challenging for professors and doctors of sciences to accept a lower position abroad. Alexander's laboratory at the Scientific Medical Research Center for Oncology concentrates on new therapies and investigates how tumors develop resistance to treatment and how to prevent it.

“My wife really wants to go. But I have a pretty high position, it's hard to find a job like that abroad. Plus my personal projects are going well. And I can't leave my employees, many of whom definitely will not go,” the scientist says.

Several programs exist to assist and support individuals who emigrate, such as Scholars at Risk. However, there are specific entry requirements that must be met, such as having a confirmed physical danger in Russia. Unfortunately, this means that not everyone is eligible for assistance.

Dismissals and the ban on “remote work”

Some scientists who had left because of the mobilization attempted to maintain cooperation with their Russian institutes and continue their ongoing projects and research. However, it is highly uncommon for them to be successful in maintaining ties. According to several sources from major Russian institutes who spoke with The Insider, management typically prevents these scientists from continuing their work. A former employee of the Moscow Engineering and Physics Institute confirmed that it was the institute's management who refused to cooperate.

“Everyone had to break off the relationship one way or another. Both my colleagues and I were willing to continue working remotely: teaching classes or advising students on writing term papers or theses. But the university did not go for that. The management said that the situation was unfavorable, “you are outside of Russia, and in general we have to check your passport for an entry stamp to let you back to work, so either return or quit.”

In many cases, scientists are required to be physically present in Russia to perform their work, particularly when they need to sign certain documents which cannot be done remotely. This is because not everyone has an electronic signature, and even if they do, it may not always be accepted. Even if the institute's administration is supportive of scientists working remotely, inspection authorities may require the presence of a specialist in Russia. As a Russian physicist explained to The Insider:

“Our signatures or some kind of approvals are required all the time. If a person is awarded a Russian grant or even several grants, he must appear in Russia at least once every 30 days. That is why it is hard to see how people can maintain connection for a long time. Some people try, but, in my opinion, it is all rather short-lived”.

Scientists who have left Russia can lose their grants given in Russia, molecular biologist Alexander is aware of such cases:

“The Russian Science Foundation, which awards the majority of grants in the country, mandates a continuous physical presence in Russia, with the exception of official business trips and vacations. They have access to border crossing databases and have informed institute heads that they will terminate grants for individuals who have emigrated. I'm aware of two graduate students who received grants to visit the United States; they were temporarily suspended from their Russian grants while abroad until they returned, according to my sources.”

Loss of access to data

When scientists are unable to maintain cooperation with their institutes, they often attempt to transfer their projects to their colleagues who remain in Russia. However, this is challenging to do when the scientist has to leave spontaneously or has already moved abroad. As a result, the research often needs to be closed or moved with them, if feasible and if there is sufficient time.

Scientists who have relocated to another country frequently lose direct access to their objects of research, such as manuscripts that have not been digitized, which are prevalent in Russia. Additionally, management often prohibits remaining colleagues from photographing archives and transferring images to those who have departed.

The primary victims of this problem are regionalists, historians, and researchers in Russia. During the early 2010s, what is now referred to as the “archival counterrevolution” occurred in Russia, resulting in a decrease in the rate of declassification of documents related to the Soviet era, and virtually no digitization of publicly accessible documents. Additionally, many archives and libraries now charge for copying, even with personal devices such as phones. For example, according to a source cited by The Insider, in one Moscow archive, the cost of photographing one page is 38 rubles, and documents can contain hundreds of pages. Despite this, simply hiring someone within the country to digitize documents is not enough; researchers need to view the catalogs themselves to determine what is accessible.

Scientists who require physical access to research objects face a significant challenge, especially when conducting field research in Russia. For instance, researchers of culture, folklore, or linguistics often need to travel to remote villages and interact with locals, making it impossible to work remotely.

Shortage of reagents

Russia's invasion of Ukraine has led to difficulties for Russian medical and biological laboratories in acquiring rare reagents. According to Marina (name changed), a scientific researcher at the Moscow Laboratory for Genome Stability Studies, around 90% of the reagents used are imported, and many of these substances cannot be substituted since there are no equivalents in Russia, China, or India. Even prior to the war, waiting periods for these reagents were long, with delivery times of up to 2-3 months in Russia compared to 2-5 days in the USA or Europe. However, the waiting times have now increased, and there is no assurance that the reagents will eventually arrive.

The laboratory where Marina works conducts basic research in the field of genome stability. She says that due to difficulties with supplies, work had to be temporarily interrupted and she had to start purchasing reagents:

“It was apparent as early as February 24 that obtaining reagents would be problematic. As a result, instead of doing experiments, our laboratory was preoccupied with purchasing reagents for two weeks starting on February 25. We were able to purchase many items up to a year in advance. We used our ingenuity to find substitutes for some reagents. For example, we procured inexpensive raffinose from AliExpress, where it is sold as a food additive.”

However, the search for a replacement for Gibco's special media for culturing human cells proved to be unsuccessful for the laboratory. Despite their efforts, scientists were unable to find a suitable substitute among analogues and had to experiment with various versions of media and serums from different manufacturers. According to Marina, they tried to find a replacement among Indian and Russian analogues, but the genetically altered cells turned out to be too sensitive and “refused” to grow on them.

The procurement of protease inhibitors, which are essential reagents used in laboratories for isolating proteins for further study, has been impossible so far. The available stocks have either been depleted or exhausted. Despite three companies assuring delivery in the spring, the reagents were not received even by December, according to Marina. The source cited by The Insider suggests that this problem may be due to logistical issues rather than sanctions.

“Most likely, after the New Year, we will no longer be able to isolate proteins. We will look for inhibitors from our colleagues at other institutes, we will look for new suppliers,” Marina said in a conversation with The Insider. For example, colleagues from Belarus helped Russian scientists with a rare plasmid. However, all this affects the speed of work. According to Marina, cell culture research has hardly progressed for six months.

Biologist Alexander has also mentioned disruptions in reagents. His laboratory works with new types of therapies in oncology, studying tumor resistance to therapy and preventing the development of this resistance. According to him, large companies supplying reagents and equipment, such as Thermo Fisher, have ceased their operations in Russia, and their reagents are being sold on the “gray market”:

“Before the war, my colleague and I had a Telegram group for sharing reagents and providing scientific support, with about 300 members. However, now the group has grown to over 5,000 people who are working together to solve these problems by searching for new suppliers.”

Severance of international ties

The invasion of Ukraine by Russia caused the closure of research projects in various institutes. Skolkovo Foundation, Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology (Skoltech), and Skolkovo Technopark were blacklisted by the U.S. Treasury Department due to their involvement in Russian defense projects. Additionally, MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) received a circular prohibiting collaboration with Russian scientists.

A scholar from the Institute of Sociology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, who studies moral and ethical changes in the Russian academic environment following the Russian invasion, told The Insider that Russian scientists are often required to disassociate themselves from domestic institutes or research centers subjected to Western sanctions in order to participate in foreign projects since collaboration at the organizational level may be effectively prohibited. Furthermore, receiving a foreign grant frequently often requires the absence of affiliation with a Russian institute.

Even research institutes that were not directly impacted by sanctions still experienced the consequences of the war. According to Marina, as of February 24, scientists from her laboratory were actively collaborating with Indian colleagues on a joint project that was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (RFBR). However, due to concerns about flight safety and uncertainty, the Indian scientists were forced to cancel their trip to Russia. Despite this setback, the researchers were able to complete their project successfully and even published a joint paper together.

“During the Cold War, cooperation in civilian science did not stop, and hopefully this will not happen now,” Marina says. But for now, according to her, many business trips have to be declined:

“Regrettably, we had to cancel our business trip to the United States this year to continue our work on studying the enzyme structure due to the unavailability of visa appointments. Nonetheless, we're still collaborating with colleagues from two U.S. labs and writing joint papers. Recently, we submitted one to Nucleic Acids Research in the UK, and we're close to completing the other.”

The Insider interviewed several scientists, and they all confirmed that international collaboration has not ceased despite the difficult circumstances caused by the war. Russian scientists have received support from their foreign counterparts. However, there have been some cases where cooperation has been halted. For instance, molecular biologist Alexander noted that Germany has formally banned such cooperation, and some institutes in the US forbid their employees from working with Russians:

“Some individuals are declining to participate in joint publications that they had been working on for years. Although there are many scientific journals available, there appears to be an increase in rejections of Russian-authored articles. Additionally, some editors struggle to find reviewers willing to review papers authored by Russians.”

“We expect funding to be cut next year, more colleagues will leave, and there will be even fewer collaborations,” Alexander says. “But for now, we expect to be able to work and at least finish the most important papers.”

Sergei, a molecular biologist who emigrated to Sweden, is also continuing to publish. His most recent paper was published in an international journal in the summer of 2022. Nor has Marina's laboratory encountered any difficulties with publishing, as several papers are currently being considered for publication in international journals.

“I work as an editor in an international journal. As of now, any paper can be published, regardless of the country of research. There are no restrictions on research funded by Russian foundations,” Marina says. “I have only encountered understanding from my foreign colleagues. As soon as the events of February 24 took place, my colleagues reached out to her, inquiring about my safety, as well as my ability to attend conferences and leave the country.”

“We were encouraged to steal the recipe and cook up stuff”

According to a researcher from the Institute of Solid-State Physics of the Russian Academy of Sciences who spoke to The Insider, lists containing hundreds of materials required for equipment and device production were circulating among research centers at the start of the war. These lists were compiled by various ministries and large companies. “Scientists were encouraged to learn how to produce them themselves, particularly by violating patent law. That is, steal the recipe and cook them up themselves,” the scientist says.

These mainly included technologies and devices related to industries such as oil, chemicals, metallurgy, and electronics. One example is the fluoropolymer production technology, which is crucial for electronics development and is yet to be replicated in Russia. According to the source, some materials such as photoresistors, which are essential for assembling electronics, can still be imported through third countries.

The Insider's source says that obtaining large and complex machines, of which there may only be dozens or hundreds in the world, is an extremely difficult task. These machines are easy to trace and it's evident who the intended purchaser is. Even if such equipment does manage to arrive in Russia, it's useless without the support of the official supplier or manufacturer. The software may be disabled, making it impossible to maintain, repair, or even operate the equipment. For instance, Russian institutes face challenges in acquiring German spectrometry equipment from Bruker due to component and software issues. Many institutes don't even try to buy such equipment, given the high likelihood that the devices, which can cost anywhere from $10,000 to a million dollars, simply won't work.

Without the support of the official supplier or manufacturer it's impossible to maintain, repair, or even operate the equipment

A graduate student who works in the field of superconducting electronics told The Insider that despite the import substitution campaign declared in 2014, many attempts to develop analogues have either not been initiated or have not yet been successful.

According to the researcher, some equipment, such as that used in the space and defense industries, has domestic alternatives available for purchase. Units for vacuum deposition of metals, for instance, have been produced in Russia since Soviet times. However, these machines were often of inferior quality compared to their Western counterparts, with a price range of 5-10 million rubles ($65,000-$130,000), and researchers are hesitant to take any risks.

The technological shortage can also impact areas that require less specialized equipment. According to Ibrahim (name changed), a bioinformatician at the Biomedical Center, there are already significant issues with accessing computing power. While many calculations can be performed on a regular computer, some heavy tasks require powerful servers, which were typically accessed through cloud technology. However, it is now very difficult or impossible to pay for these services.

No exemption from mobilization

The inability to obtain a deferment from military service has become a major factor compelling young scientists to leave Russia and preventing them from returning. According to Valery Falkov, the Minister of Education and Science, currently only Russian university teachers holding academic degrees, such as candidates and doctors of sciences, have received deferments from mobilization.

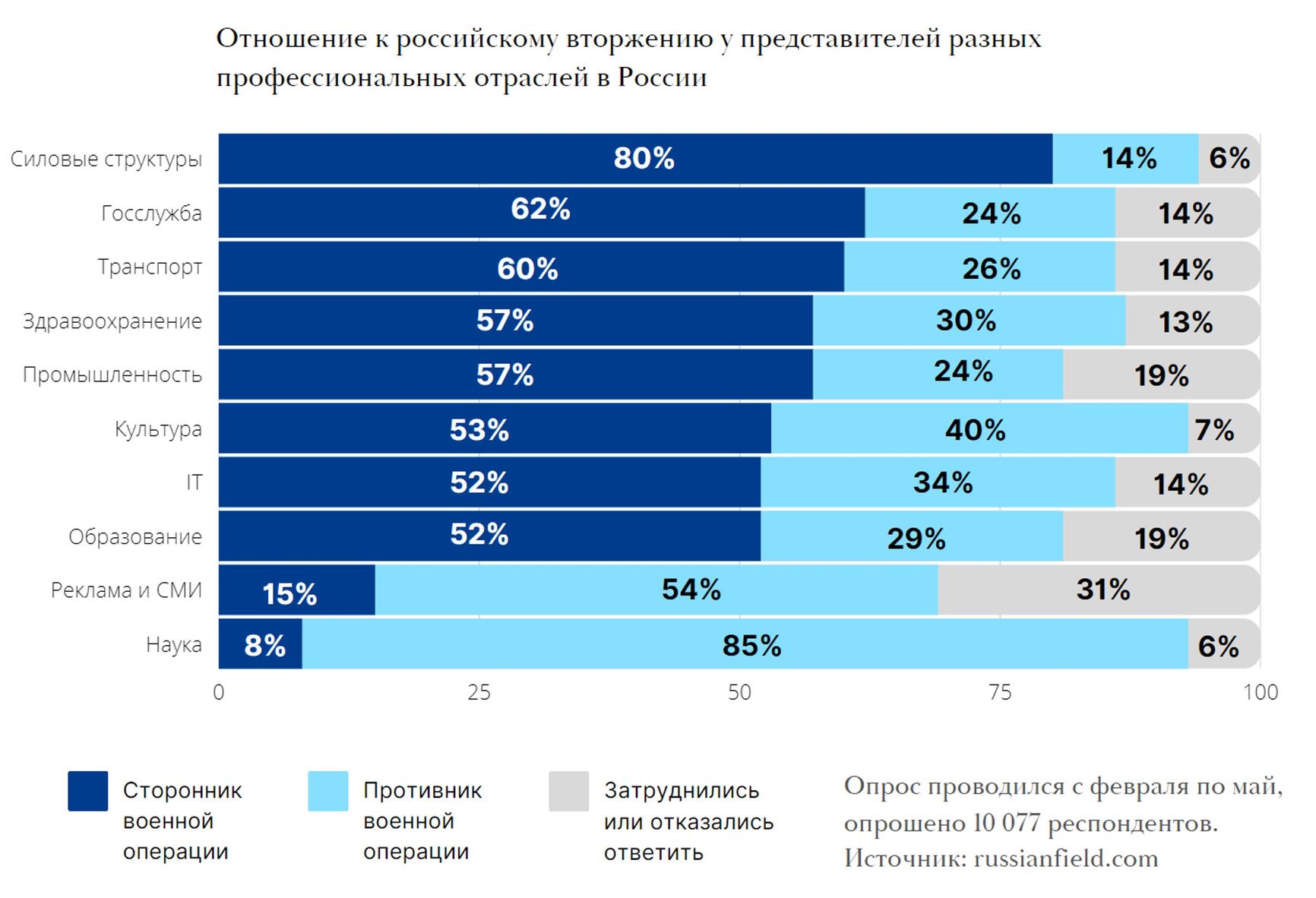

Young specialists without such degrees may still be drafted, even though there are many opponents of the war among Russian scientists. In the first days of the Russian invasion, over 7,000 scientists signed a letter opposing the “special military operation” in Ukraine. In the spring, opinion polls indicated that 85% of scientists were against Russian aggression. Furthermore, according to the sociological research project “Russian Field,” only 8% of scientists supported the war against Ukraine.

“Many people left when mobilization was announced ... However, many returned when their institutes were able to secure exemption,” Alexander says. He also went to Belarus for a month at the end of September, taking a vacation.

The institute where Alexander's lab is located was able to secure exemptions for all employees aged from 30 to 50 who had scientific degrees. Some of them had previously received draft notices, but in the end they were not drafted. The main question for all scientists became whether to leave or stay. Sergei, who departed for Sweden, shares this viewpoint.

“They didn't send me a draft notice, but that's not much comfort: it's clear now that these people will stop at nothing.”

Several scientists left the country after their family members received draft notices from the military enlistment office. Marina, a molecular biologist and candidate of sciences who works at a Moscow laboratory, is currently residing in Moscow and preparing to defend her doctoral dissertation, but she is effectively compelled to live between two countries. The war was a tragedy for her family.

“My husband's mother lives in Ukraine, it's a personal tragedy for him, he left Russia. No one in our laboratory has left, I continue to work, I live in two countries, although I have received job offers.”

No money, no research

There are two groups of Russian scientists: some focus more on national projects, attending internal conferences and publishing in domestic journals, while others are more oriented towards international science, participating in joint developments and publishing in international journals. As globalization in science has progressed, the percentage of “internationalists” has increased. Currently, they are the ones who are suffering the most, which may result in a decline in the quality of international cooperation.

According to The Insider's sources, the departure of the best scientists in their respective fields, who have strong connections to international science, is expected to negatively impact the quality of Russian specialists. Many of these professionals are involved in teaching and research leadership in addition to their research work. As a result, their departure greatly affects the motivation and aspirations of undergraduate and graduate students who are pursuing a career in science.

The Insider's interlocutors express concern that the frequency of “conscious plagiarism” among Russian scientists, where they use data from foreign colleagues' studies without crediting them, may increase. Due to limited access to foreign experience, Russian scientists may resort to “reinventing the wheel” and duplicating discoveries that have already been made by their foreign counterparts. This could slow down the progress of Russian science as modern science is not confined to national boundaries. The products and services that both ordinary citizens and scientists use today are the result of international cooperation. If scientific research becomes isolated within the country, comparative research, which is an essential area of modern research in all fields, could become unfeasible.

The best scientists in their respective fields have left Russia

“Overall, I think the last days are coming for [Russian] science. Or they are already upon us,” Olga Matveeva, a molecular biologist and founder of Sendai Viralytics, a biotech company from the United States, told The Insider. “It's just that many in Russia haven't realized it yet.”

Russian science is also expected to face a reduction in funding. The draft budget for 2023-2025, which has been published, outlines plans to allocate 492 billion rubles ($6.33 billion) to civilian science in 2023, 490 billion rubles ($6.3 billion) in 2024, and 473 billion rubles ($6.09 billion) in 2025. This is in contrast to the 626 billion rubles ($8.06 billion) allocated in 2021 and 569 billion rubles ($7.33 billion) in 2022. The significant reduction in funding may result in a decline in the quality of equipment and resources available to research institutes and centers, such as the inability to replace or repair old equipment. Additionally, scientists’ salaries, which are already quite low except for a few areas such as physics and bioinformatics, may also be impacted.