Despite his anti-immigrant rhetoric, in the 2024 election 46% of recent migrants from Latin America voted for Trump. Although his support among Latinos is falling, the phenomenon that made such support possible in the first place remains: many assimilated migrants begin to exhibit anti-immigration political preferences. Especially in times of economic instability, newcomers are mistakenly perceived by established migrants as competitors for jobs (even though empirical data shows that increases in immigration does not lead to higher unemployment). For those who have already obtained citizenship, freedom of movement is no longer a priority, as their concerns shift to other social issues.

Content

Assimilation and illusory job competition

Fear of being associated with “bad” migrants

Influence of the country of origin

Shift of priorities

Since the very start of his return to the White House, Donald Trump has waged a fierce campaign against migrants. One of its victims in August 2025 was Alexander Gud, the former press secretary of the Libertarian Party of Russia, who was seeking asylum in the U.S. (and who himself is a staunch supporter of deportations). Gud would have found himself back in Russia had he and his wife not boarded a flight to Cairo during a layover in Istanbul.

Given the rise of anti-immigrant policies worldwide, such cases are likely to increase. Under such circumstances, having a prestigious profession or taking a political position in support of the powers-that-be offer diminishing protection against deportations and visa restrictions. Germany has practically halted the issuance of humanitarian visas while simultaneously beginning negotiations with the Taliban movement on the deportation of Afghans. The U.S., meanwhile, is deporting even deserters from the Russian army and imposing restrictions on professionals arriving on high-skilled worker visas. So what drives migrants to oppose freedom of movement in a context where further restrictions can put them or their loved ones at risk?

Assimilation and illusory job competition

Migrants who are opposed to migration are a fairly common phenomenon. The head of the Gelsenkirchen branch of Alternative for Germany (AfD), Enksi Seli-Zaharias, is originally from Albania. She mobilizes the city’s Turkish diaspora against Arabs, emphasizing that the latter receive passports almost hassle-free, while Turks have to make significant efforts to integrate into society.

As a rule, recent arrivals tend to be much more favorable toward migration than locals. However, as they assimilate, they often adopt a different view. In the UK, for example, 83% of locals and 53% of immigrants who have lived in the country for more than five years oppose the arrival of further newcomers. However, among those who have lived in the country for less than five years, only 33% are against welcoming new immigrants.

Children of migrants who are born in the new country tend to align more closely with native-born residents than with their own parents on issues such as same-sex marriage and migration, according to surveys conducted in 24 European countries.

Translated from Italian, “Il Secondo” means “The Second,” referring to the second generation of migrants who arrived in the 1970s from Italy and Spain, while new migrants mostly come from the Balkans or Portugal.

Children of migrants are closer to native-born residents than to their own parents in their views on unemployment, same-sex marriage, and migration

In a 2014 Swiss referendum that proposed limiting migration, people with migration experience voted much like the locals — largely in favor of the initiative. A study of this vote, dubbed “Immigrants Against Immigration,” showed that support for restrictions was most common among migrants who lacked in-demand skills, as well as among those who had integrated into the Swiss hierarchy by adopting the widespread Secondo identity.

In all of these cases, immigrants’ concern about the influx of “rivals” was economically motivated. In the UK, low-income natives and newcomers alike were more negative toward migration than their wealthier peers. In Germany, the aforementioned Albanian immigrant AfD party branch head lives in a region experiencing economic decline.

Among native residents, this pattern is widespread. Negative attitudes toward migration have been found to be stronger among those who fear competition from foreigners. Conversely, respondents with skills that gave them an advantage tend to be more favorable. Workers in sectors anticipating job growth are also less likely to oppose migration.

Numerous studies show that first-wave migrants’ fears are unfounded: new arrivals do not cause higher unemployment — neither in the regions they move to nor within their own diaspora.

Migrants themselves are much more vulnerable to competition than locals, whose main advantages are social connections and better language skills. Still, once newcomers establish themselves in a new place and obtain citizenship, they increasingly begin to oppose immigration.

Fear of being associated with “bad” migrants

Another factor driving immigrants to oppose those who are just now making the trip is the fear of being associated with “bad” newcomers. In the U.S., successful immigrants worry about being equated with their low-skilled undocumented peers. Notably though, in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, where the proportion of “illegal” migrants is lower, this pattern is not observed.

Translated from Italian, “Il Secondo” means “The Second,” referring to the second generation of migrants who arrived in the 1970s from Italy and Spain, while new migrants mostly come from the Balkans or Portugal.

Migrants oppose migration out of fear that they will be lumped together with “bad” migrants

The desire to distance themselves from “bad” immigrants is particularly pronounced among Muslims. In-depth interviews with highly skilled African immigrants in France showed that, when facing racist prejudices, people of different religions employed different coping strategies. Members of all groups appealed to the secular nature of French society, emphasizing the importance of tolerance and universalism for European culture. At the same time, they framed racism as a sign of backwardness and uncivilized behavior.

However, Muslim immigrants faced a double stigma that is linked both to racism and Islamophobia. Rather than confronting the latter, they tended to downplay or even conceal their religious identity.

Influence of the country of origin

For migrants from socialist and post-socialist countries, the history of their homeland plays an important role, as negative experiences with the political left push them to vote for right-wing parties more often — despite those parties’ frequent xenophobic rhetoric. People from Venezuela and Cuba, where socialist dictators hold power, tend to support migration restrictions in their new countries, whether they have moved to the U.S., Argentina, or Spain. Moreover, they oppose newcomers more actively than both locals and other migrants from Latin American countries.

Translated from Italian, “Il Secondo” means “The Second,” referring to the second generation of migrants who arrived in the 1970s from Italy and Spain, while new migrants mostly come from the Balkans or Portugal.

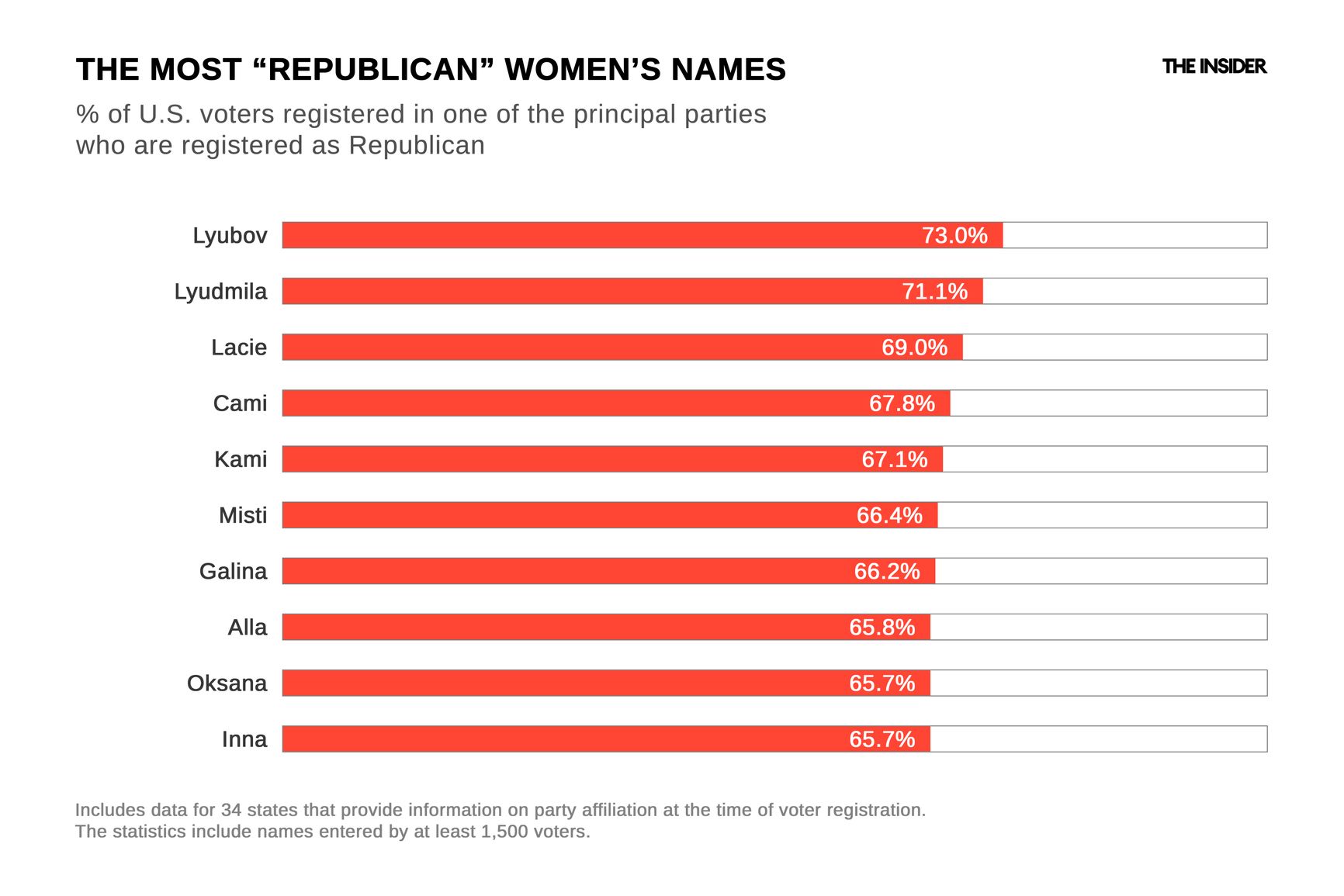

In the U.S., 58% of Cubans and 32% of other immigrants from Central and South America vote Republican. Notably, the same trend applies to immigrants from post-Soviet countries. Out of the ten female first names that tend to lean Republican by the widest margin, six are of Slavic origin.

Translated from Italian, “Il Secondo” means “The Second,” referring to the second generation of migrants who arrived in the 1970s from Italy and Spain, while new migrants mostly come from the Balkans or Portugal.

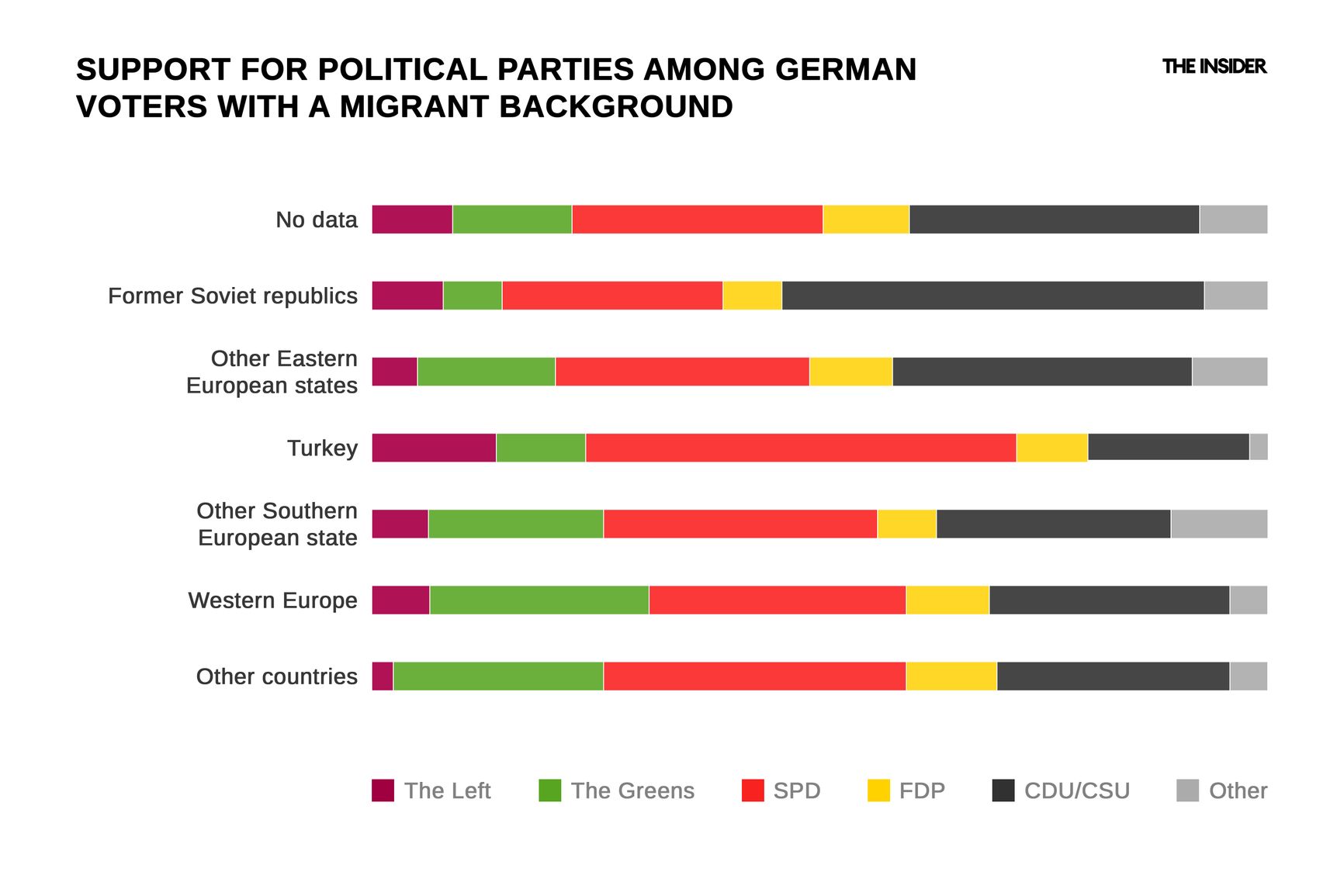

A more detailed analysis by The Washington Post shows that people with Slavic names are more likely to support Republicans, whereas those with Latin or Arab names typically vote for Democrats. The pattern is similar in Germany, where immigrants from Eastern Europe and former Soviet republics traditionally voted for the conservative CDU more often than both Germans and other immigrants did. With the rise of the far-right AfD and the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance, migrants who arrived from the east have disproportionately shifted their political preferences even further to the right. The fact that AfD initially gained popularity in East Germany speaks volumes.

Translated from Italian, “Il Secondo” means “The Second,” referring to the second generation of migrants who arrived in the 1970s from Italy and Spain, while new migrants mostly come from the Balkans or Portugal.

Living under right-wing dictatorships appears to have a similar effect — in the opposite direction, of course. Voters who grew up under right-authoritarian regimes are less likely to support far-right parties, according to a study conducted in 39 democracies on the influence of residents' backgrounds on their political preferences. The Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939 affected the first free elections in 1977 on both sides: those who suffered repression at the hands of the nationalists were more likely to vote for the left, while those who were persecuted by the left voted for the nationalists.

Shift of priorities

There is a common stereotype in the West that immigrants, especially from Arab countries, impose their culture on the host society, gradually displacing progressive values. However, a diametrically different prejudice argues that the left promotes immigration as a way to expand its voter base.

Although the U.S. Democratic Party long followed the second principle, treating Latin Americans as its default electorate, the Republicans — aware that this diaspora would shape 21st-century America — has frequently courted it since the days of George W. Bush, emphasizing the GOP’s piety and traditionalism while supporting small businesses. As a result, in the 2004 election, George W. Bush secured the support of 44% of Hispanic Americans.

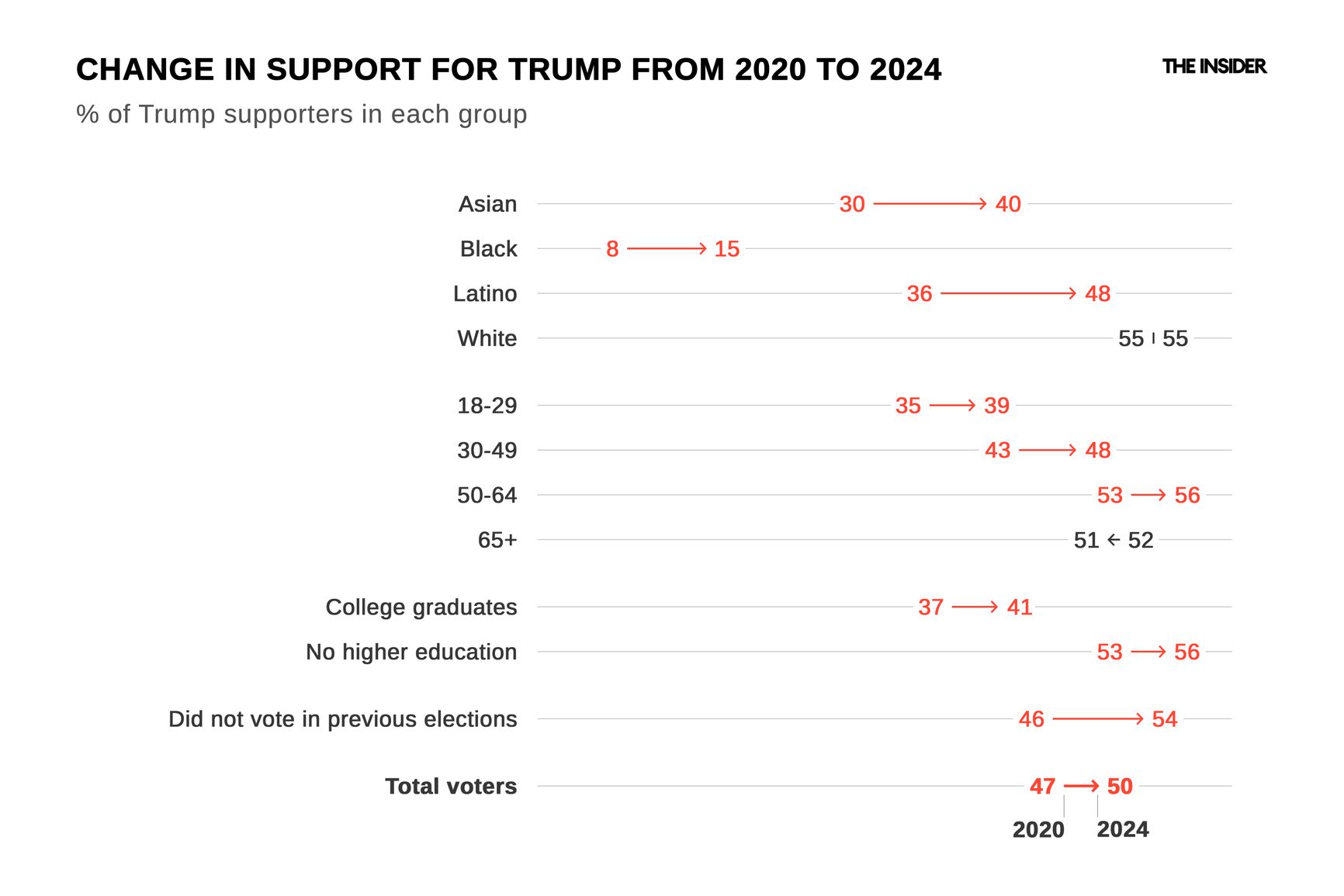

Despite rhetoric largely built on demonizing “Latinos” in general — and Mexicans in particular — Donald Trump has increased his support among this group from one election to the next. In 2016, he received 28% of their votes, in 2020 it was 32% and in 2024 the figure rose to 46%.

Translated from Italian, “Il Secondo” means “The Second,” referring to the second generation of migrants who arrived in the 1970s from Italy and Spain, while new migrants mostly come from the Balkans or Portugal.

Despite his anti-immigrant rhetoric, Donald Trump has been steadily increasing his support among Hispanic Americans year after year

Although some Hispanic voters rejected Trump, he appealed to a large segment by focusing on issues that are more important to them than culture wars and migration. Latin Americans who had already obtained U.S. citizenship and the right to vote were less concerned about potential restrictions on migrants; however, they felt strongly about the economic and labor market issues that Trump emphasized. Two other factors of appeal were Trump’s religious beliefs and his macho image, which struck a chord with Hispanic men in particular.

Translated from Italian, “Il Secondo” means “The Second,” referring to the second generation of migrants who arrived in the 1970s from Italy and Spain, while new migrants mostly come from the Balkans or Portugal.