On October 18, Iran’s Foreign Ministry announced that the country’s nuclear program is no longer bound by any outside obligations, as the 2015 agreement between the Islamic Republic and a collection of world powers has officially expired. The West, meanwhile, has found no new arguments capable of persuading Tehran to compromise. But as the attack on Iranian nuclear facilities this past summer showed, Donald Trump and Benjamin Netanyahu would prefer a quick missile strike to prolonged negotiations. One way to extract concessions from Tehran may be to demonstrate the readiness to launch just such a repeat strike.

Content

Very long-lasting sanctions

Enter Trump

The UN steps in

The likelihood of a new confrontation

Very long-lasting sanctions

The U.S. imposed its first sanctions on Iran shortly after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, in response to the seizure of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and the prolonged hostage-taking of its staff. Other Western countries, however, were slow to join the effort. It was only in the 2000s, when Iran was suspected of developing nuclear weapons, that Europe decided to take part in the pressure campaign. In turn, the Iranian regime openly asserted its right to enrich uranium. As a result, beginning in December 2006, the UN Security Council started imposing — and gradually tightening — sanctions of its own.

Between 2010 and 2012, the U.S. and the European Union began to target not only Iran’s nuclear program but also its broader economy. The new Western restrictions focused on the country’s energy sector, banking industry, and trade. Meanwhile, Washington tightened secondary sanctions, imposing penalties for those who continued doing business with Tehran. The EU stopped importing Iranian oil, froze the country’s assets, and enacted visa restrictions. These measures dealt a heavy blow to Iran’s economy: oil exports plummeted, the rial collapsed, and foreign companies began pulling out of the country.

At the same time, the West, particularly Europe, still sought to reach a compromise by persuading Tehran to abandon its nuclear ambitions. The arrival of Barack Obama in the White House gave new momentum to the diplomatic process, ultimately leading to the signing of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2015. The agreement called for a reduction in the number of Iran’s uranium-enrichment centrifuges, a substantial decrease in its stockpile of enriched material, and the opening of the country’s nuclear facilities to IAEA inspections — all in exchange for the gradual easing of sanctions. UN Security Council Resolution 2231, adopted on July 20, 2015, formalized the deal and established a snapback mechanism, allowing for the rapid reinstatement of sanctions in the event of serious violations.

Uranium enrichment facilities in Iran

Israel consistently opposed the agreement, arguing that it was too lenient to adequately restrain Iran’s nuclear ambitions. Addressing the U.S. Congress in March 2015, Prime Minister Netanyahu said the deal “doesn’t block Iran’s path to the bomb; it paves Iran’s path to the bomb.” According to Netanyahu, the agreement “would not shut down a single nuclear facility in Iran, would not destroy a single centrifuge in Iran, and will not stop R&D on Iran’s advanced centrifuges.” Nevertheless, the deal went into effect.

Enter Trump

In late 2016, Donald Trump won the U.S. presidential election and immediately made it clear to Netanyahu that he was far more sympathetic to Israel’s concerns than his predecessor had been. In the spring of 2018, Netanyahu announced that his country’s intelligence services had obtained evidence proving that Tehran had been deceiving the international community all along, secretly pursuing a military nuclear program. Trump promptly announced the U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA and the reinstatement of American sanctions against Iran. Although European countries refrained from following suit, the threat of secondary sanctions left them with little room to maneuver. The German petrochemical giant BASF, which had returned to the Iranian market in 2016 following the Obama-era deal, declared that it would comply with the new restrictions. Other major companies, including Renault, PSA, and Siemens, were compelled to do the same.

Israeli intelligence claimed to have obtained evidence of Iran’s military nuclear program

Notably, on Iran’s side, the JCPOA negotiations were led by the team of reformist President Hassan Rouhani, while Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei was skeptical from the outset. He stated that despite the agreement, Iran would not abandon its confrontation with the U.S. or change its Middle East policy. After Washington’s withdrawal from the deal, Khamenei sharply criticized Trump and declared that he no longer trusted either the Americans or the European countries that had signed the agreement.

The UN steps in

The agreement with Iran was originally intended to remain in effect for ten years, with the hope that, by 2025, Iran’s reintegration into the wider world would provide enough of an incentive to forgo the resumption of its nuclear program. That didn’t happen, and as the October 2025 expiration date neared, voices in the West began calling for the reimposition of international sanctions. In late August, the foreign ministers of the United Kingdom, France, and Germany — the so-called “E3” — issued a joint statement accusing Iran of violating its obligations under the accord, including via the accumulation of enriched uranium, the denial of access to IAEA inspectors at nuclear sites, and the refusal to ratify additional protocols.

In light of these findings, the E3 members moved to reinstate the sanctions through the snapback mechanism while also expressing readiness to ensure Iran’s full compliance with the agreement through diplomatic means. However, Tehran showed no intention of returning to the negotiating table, and by the end of September, the sanctions had come into effect.

By then, Trump was already back in power. In March 2025, he had offered Iran’s leadership a return to negotiations on the nuclear program, setting a clear deadline of 60 days to make a decision. After that period expired, Trump announced that Iran had made no concessions.

This past June, immediately after Trump’s ultimatum expired, Israel carried out strikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities. The U.S. later joined the operation. The bombings caused severe damage to sites in Natanz, Fordow, and Isfahan. The exact extent of the damage remains unknown, but according to Israeli and U.S. intelligence estimates, Iran’s nuclear program has been set back by at least two years.

The aftermath of Israel’s summer strike on Iran

Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesman Esmaeil Baghaei confirmed that the country’s nuclear facilities had sustained serious hits, noting that significant destruction was caused by Massive Ordnance Penetrator (MOP) bombs dropped by U.S. aircraft. Mohammad Eslami, head of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran, added that the use of bunker-busting bombs had rendered some facilities inoperable.

The fate of roughly 450 kilograms of enriched uranium remains unclear. According to Israel, the material was stored at the sites targeted by the bombings, but Tehran has released no information about the condition of its stockpiles. In a September interview with Fox News, Netanyahu stated that Israeli intelligence knows the exact location of the uranium and reassured that it currently poses no threat. In short, by the time international sanctions were reinstated, Iran’s nuclear program was already in a highly degraded state.

The country’s economic situation also remains dire. According to the International Monetary Fund, Iran’s GDP growth in 2025 is expected to stay below 0.3 percent, primarily due to a decline in oil exports amid tighter sanctions. Exports of Iranian goods and services are projected to fall by 16 percent compared to 2024, while imports are expected to drop by 10 percent. Inflation may range between 37 and 43 percent, and the national debt is estimated at 40 percent of GDP. Unless Iran manages to sell oil in large volumes — or at very high prices, around $163 per barrel — it will be unable to offset its 2025 budget deficit.

By the time international sanctions were reinstated, Iran’s nuclear program, defense, and economy were already in a dire state

In the fall, Iran’s currency hit another record low on the black market: over 1 million rials to the dollar. Meanwhile, the Iranian parliament approved a monetary reform: one new rial will be equal to 10,000 old ones. A new subunit, the qiran, will also be introduced, equal to 0,01 of a rial.

Iran struggles the most with its infrastructure. This past spring, Ali Nikbakht, head of Iran’s Power Plant Association, warned that in 2025–2026 the country would face an electricity shortage of 25,000 megawatts. The causes of the energy crisis include sanctions, equipment deterioration, and inefficient management. During the summer, amid a severe drought, water supply disruptions were recorded in 30 of Iran’s 31 provinces, including the capital.

The likelihood of a new confrontation

In addition to the destruction of its nuclear facilities, the 12-day war with Israel put a dent in Iran's military capability. The Israeli army disabled Iran’s air defense systems and destroyed a significant number of missiles and launchers. Nevertheless, the Iranian regime immediately began working to restore its defense capacity. Iran’s defense industry will strive to supply the armed forces with higher-quality weapons, Iranian Defense Minister Aziz Nasirzadeh said this past August.

The 12-day war with Israel put a dent in Iran's military capability

Western media reported activity at the destroyed plants in Shahroud and Parchin, where solid rocket fuel had been produced. However, Iran currently lacks the equipment necessary for such production — specifically, industrial mixers. Since these cannot be manufactured domestically, the authorities are left relying on potential supplies from China, but so far at least, there have been no reports that Beijing is prepared to provide Tehran with this equipment.

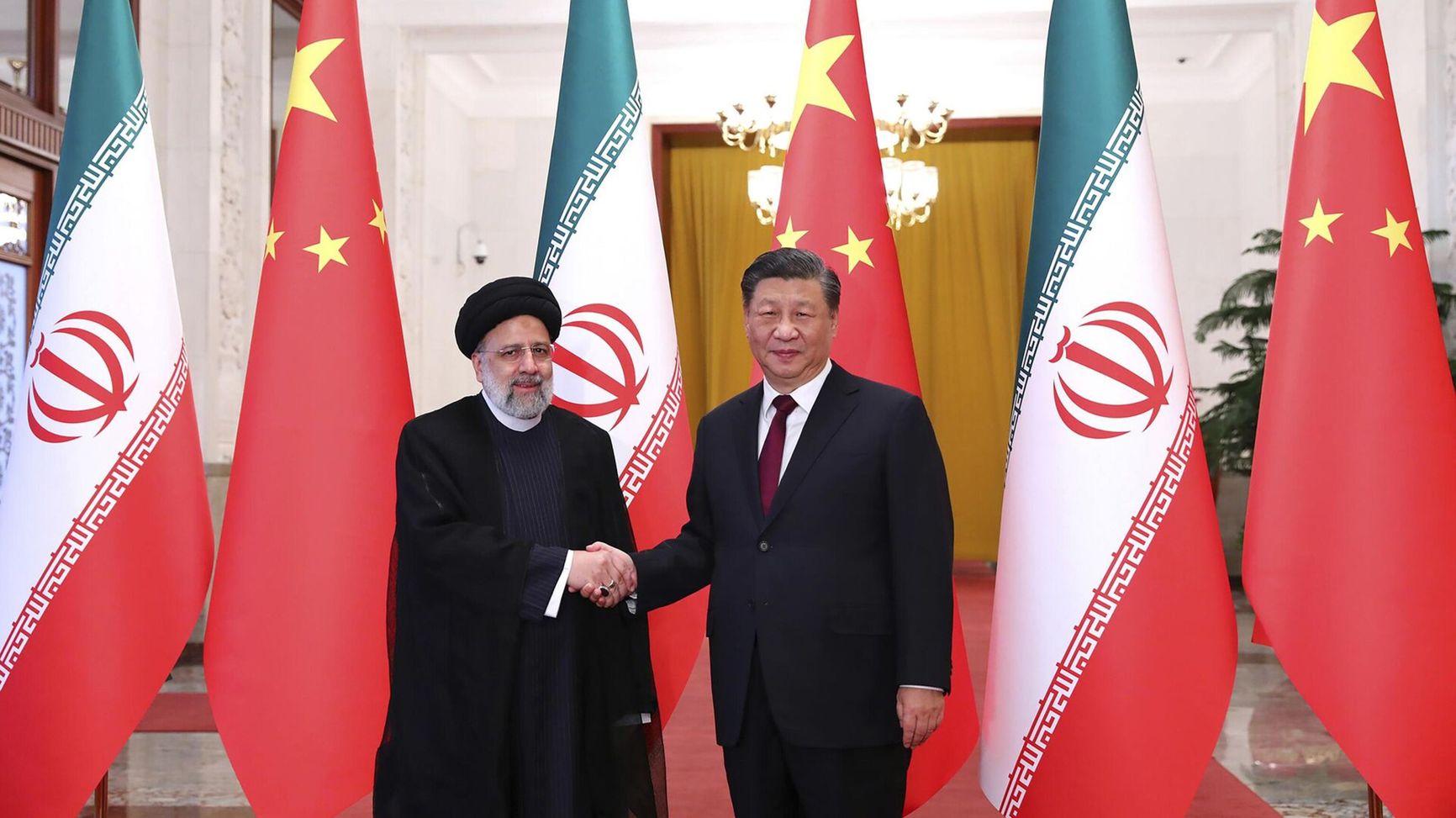

Still, China remains a reliable partner of the ayatollahs’ regime when it comes to trade, purchasing Iranian oil despite sanctions. Much less is known about the two countries’ military-technical cooperation. Nevertheless, China is currently the only Iranian partner capable of supplying it with enough missiles to help restore its defense capacity, as Russia’s defense industry has turned inward due to the war in Ukraine.

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and Chinese President Xi Jinping

There were also reports of Chinese and Russian combat aircraft being supplied to Iran. According to unconfirmed reports, Iran has received 10 of the ordered 40 Chinese-Pakistani J-10 fighter jets. In addition, Moscow delivered several MiG-29 fighters to Tehran (even though Iran had previously purchased the more advanced Su-35), possibly as a temporary replacement for the aircraft lost during the 12-day war.

Against this backdrop, Esmail Kowsari, a retired general and a member of the Iranian parliament’s Security and Foreign Affairs Commission, called for developing domestic production of long-range missiles capable of striking targets inside Israel, along with U.S. military bases in the region.

Current and former representatives of the Iranian regime have issued numerous belligerent statements, though most of them are largely defensive in tone. Former Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps commander General Yahya Rahim Safavi warned on June 29 that if Israel attacks Iran again, the response will be “devastating.” At the same time, the general admitted that the war had caught Iran off guard, exposing a “strategic intelligence weakness.” In September, after the reinstatement of sanctions, he called Europe an enemy of Iran while emphasizing China’s role as a reliable ally of the regime and of the so-called “forces of resistance” as a whole.

Iranian General Yahya Rahim Safavi admitted that Israel’s attack caught the country off guard, revealing a “strategic intelligence weakness”

Under the current circumstances, the likelihood of a new military confrontation between Iran and Israel or the U.S. remains quite high. Tehran has shown no willingness to make concessions on its nuclear program, ignoring Western demands. Iran’s parliament, meanwhile, continues to push for withdrawal from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

Iran’s military potential remains low: its air defense systems have yet to be restored, its missile arsenal is smaller than before the 12-day war, and Hezbollah — the Lebanese terrorist group that served as Iran’s deterrent tool against Israel — has been crushed. Nevertheless, the Islamic Republic continues to support Hezbollah in hopes of rebuilding its capabilities. In late January 2025, Israel accused Iran of using its diplomats to smuggle millions of dollars in cash into Lebanon for the group, and Iranian officials have openly urged the Lebanese government not to disarm Hezbollah. A potential Israeli-American operation could now be motivated by Iran’s intransigence and facilitated by its weakened defenses.

In 2015, Iran’s leadership agreed to a nuclear deal only after significant concessions were offered by the West. Now, however, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei refuses to engage in talks with Washington altogether. In August 2025, he described his country’s differences with the U.S. as “irreconcilable,” and in September, he stated that any negotiations would be futile so long as the U.S. demands that Iran abandon its nuclear ambitions.

Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has no desire to hold talks with the U.S., believing the differences with Washington to be “irreconcilable”

Just days ago, Iran’s Foreign Ministry announced that the country no longer considers itself bound by restrictions on its nuclear program, as the JCPOA has expired — yet another indication that Tehran is not inclined toward constructive dialogue.

Admittedly, according to U.S. intelligence, Iran did once suspend work on its nuclear program — in 2003. At that time, in addition to mounting international pressure, the American invasion of Iraq played a key role. Tehran may have feared that after U.S. forces toppled the Taliban in Afghanistan and Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq, they could choose the ayatollahs as their next target.

Consequently, with the Iranian regime flatly refusing dialogue, the West has just one diplomatic path left: to convince Tehran that the U.S. and its allies are prepared to orchestrate the regime’s downfall, and that China and Russia would be unable to protect the ayatollahs in such a scenario. Only such a threat could force Ali Khamenei to come to the negotiating table. If he remains unyielding, then, as the most recent war showed, neither Israel’s current leadership nor the Trump White House are inclined to bargain when a missile strike might offer a more effective solution.