Leo XIV – Robert Francis Prevost – has succeeded the late Pope Francis. His election came as a surprise even to many Catholics. He became the shepherd of a Church that is deeply divided between its liberal and conservative camps. American society at large is split along the same lines, which means the new pontiff will inevitably be perceived within this political context. His initial statements have sent mixed signals: while some have gone so far as to label him a communist, others have already accused him of excessive conservatism. Whether the new Pope wants it or not, he is bound to become a political figure. The position of the Catholic Church can play an important role in a society torn in two – on issues ranging from abortion and LGBT rights to seemingly distant matters like the war in Gaza and global climate change.

Content

An American Catholic – who is that?

A bad Catholic, a good American

Liberals and conservatives

A new Pope: yours or ours?

An American Catholic – who is that?

In recent years, Catholics have become a common sight at the summit of American politics. Former President Joe Biden is Catholic, as are current Vice President J.D. Vance and Secretary of State Marco Rubio. Yet each of them represents a different Catholic constituency.

According to the Pew Research Center, Catholics make up the second-largest Christian denomination in the U.S. — 20%, behind 23% for Evangelical Protestants. They are relatively active (29% report attending church services weekly), and they are fairly well-educated, with 35% holding a bachelor’s degree. Crucially, Catholicism in America is a religion of later-wave immigrants.

Most of the early North American colonists came from England, the Netherlands, and Germany, laying the “Protestant DNA” foundation of U.S. culture. In the 19th century, the Catholic population of America grew significantly due to the arrival of Irish, French, and German Catholics, and by the end of the century, this group swelled thanks to large-scale migration from Southern and Eastern Europe (Italians, Hungarians, Greeks, Poles, Lithuanians). According to 2023 data, there are nearly 62 million Catholics living in the U.S. – more than 18% of the country’s population.

According to 2023 data, there are nearly 62 million Catholics living in the U.S. – more than 18% of the country’s population

In the 20th century, two world wars also led to mass migration of Europeans to the U.S., but throughout this period a large share of the Catholics coming to the country were from Latin America. They arrived in waves: after the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) and the subsequent peasant uprising in Mexico (1926-1929), and later following the Cuban Revolution in 1959. Many came through Mexican labor migration starting in the 1960s, and during the overall instability across Central and South America in the 1980s. A significant number of “new” Catholics also arrived from Asia (Vietnam, Korea, the Philippines) and the African continent.

As a result, Catholics in the U.S. today are primarily either “white” (54%) or of Latin American origin (36%), with the latter group consistently growing. Most “white” Catholics are Republicans, while Catholics of Latin American descent are mostly Democrats (although they can lean toward supporting Trump and the Republicans, as seen in the data from the recent presidential election and the role of Marco Rubio and several other officials in the new President’s administration).

The conflict between the supporters of Democrats and Republicans over numerous political, social, and cultural issues had been brewing for a long time, but it fully erupted into the public sphere during Donald Trump’s first presidential term. The religious beliefs of American Catholics, refracted through the lens of the left-right political and cultural battle – between “woke” and “Trumpist” camps – mirror the broader public debates about what kind of country America should be.

In this sense, new Pope Leo XIV is not just the spiritual leader of American Catholics – depending on his stance, he will inevitably become an object used by both Republicans and Democrats in heated political debates about the future of the United States. The roots of this highly politicised perception of religion can be found in the specific history of American Catholicism.

A bad Catholic, a good American

Catholics in America were not always a part of the political mainstream. When the U.S. was being founded, migrants from the Old World – torn by Catholic-Protestant conflicts – attempted to create a country based on Enlightenment ideals, where religion could shape morality but would not influence governance. In contrast, the Catholic Church in Europe had historically been closely tied to power.

Most of those founding fathers were Protestant, as were most members of the country’s ruling class. Until the 1960s, Catholics in the U.S. often faced prejudice and suspicion from fellow citizens, who believed that the Catholic worldview was incompatible with the core principles of American society. In 1949, American writer Paul Blanshard published an anti-Catholic book titled American Freedom and Catholic Power, in which he claimed that the Catholic Church was “an undemocratic system of alien control.”

Thus, until the 1960s, Catholicism in the U.S. was largely the religion of outsiders and ethnic minorities in big cities. This, in turn, led to a heightened Catholic interest in social issues and strong support for the Democratic Party.

Until the 1960s, Catholicism in the U.S. was largely the religion of outsiders and ethnic minorities in big cities

One of the most famous American activists of the 20th century, Dorothy Day, was Catholic. In 1933, working together with French Catholic migrant Peter Maurin, she founded the Catholic Worker Movement. Working-class Catholics made up a significant portion of the liberal-democratic New Deal coalition under Franklin Roosevelt, which focused on fighting poverty and unemployment — the effects of the Great Depression.

The 1960s and 1970s shook America: civil rights protests, women’s rights movements, the sexual revolution, race riots, anti-Vietnam War demonstrations, and a surge of socialist and pacifist ideas. During these decades, American Catholicism became part of the political mainstream while also becoming more divided along party lines.

In 1960, the U.S. elected its first Catholic president: John Fitzgerald Kennedy, a third-generation Irish-American. His ascension to the White House showed that a Catholic could rise to the highest office in the country, but only after publicly stating that: “I am not the Catholic candidate for president. I am the Democratic Party’s candidate for president, who also happens to be Catholic.”

Liberals and conservatives

Shortly after American society had become enamored with the Catholic president Kennedy, Pope John XXIII convened the Second Vatican Council in Rome (1962–1965). This event opened the Catholic Church to globalisation and, at the same time, to decentralisation. Many traditional restrictions were lifted – for example, the Mass could now be celebrated in local languages rather than in Latin, and local bishops and lay councils were granted more autonomy.

Thanks to the Second Vatican Council, the Church opened itself to freer discussions on topics such as contraception and sexuality, the rights and role of women in the modern world, the Church’s relationship with contemporary culture, the secular world and science, the balance between laypeople and clergy, capitalism and poverty, and even environmental stewardship.

Thanks to the Second Vatican Council, the Church opened itself to freer discussions on topics such as contraception and sexuality, the rights and role of women, capitalism, and poverty

The Church’s new teachings came to be associated, for some Catholics, with an unstable world and the breakdown of traditional American values. In the 1960s and 1970s, many members of the clergy and monastic orders left the Church and led secular lives.

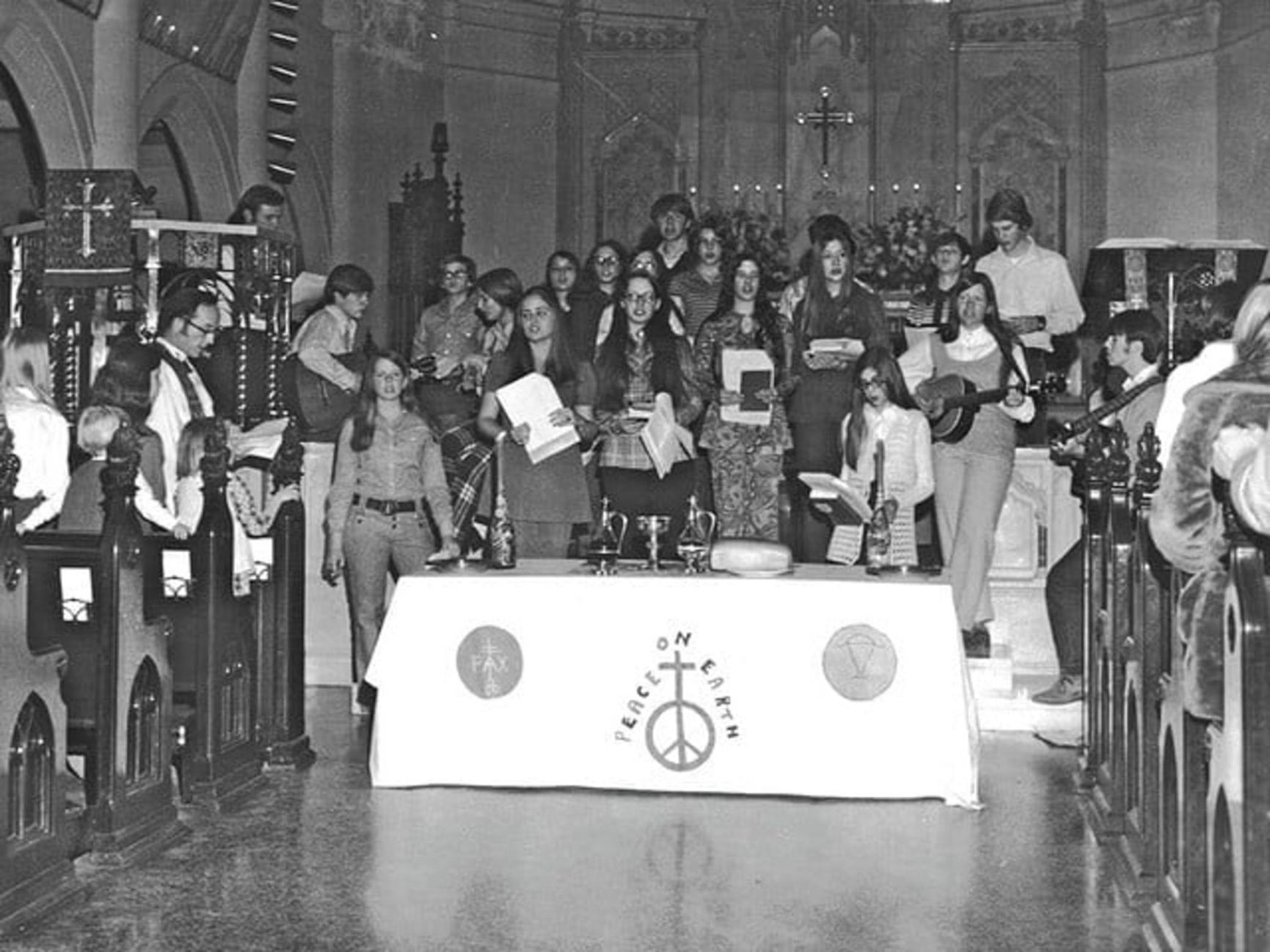

New religious practices emerged – for instance, “guitar masses,” where priests and congregants gathered around improvised altars to sing adapted religious or contemporary songs.

There were hippie priests who allowed non-believers and Protestants to participate in services – they wore handmade vestments adorned with flowers and peace symbols, played Beatles music, and gave liberal, anti-war sermons. All of this shocked the more traditionally minded Catholics.

Folk singers at a guitar mass, 1970s

At the same time, the greater flexibility and freedom in decision-making allowed American Catholics to adapt their beliefs to the specific character of their country. However, this very freedom also split them into political camps, each with its own vision of how America should be structured and what its future ought to look like.

The more conservative Catholics associated Church teachings with a traditional way of life and believed the Church should shape the moral foundations of its followers. The liberal wing, on the other hand, insisted that believers must be guided primarily by their own conscience – including in decisions about contraception, abortion, divorce, premarital sex, and whether or not to have children at all.

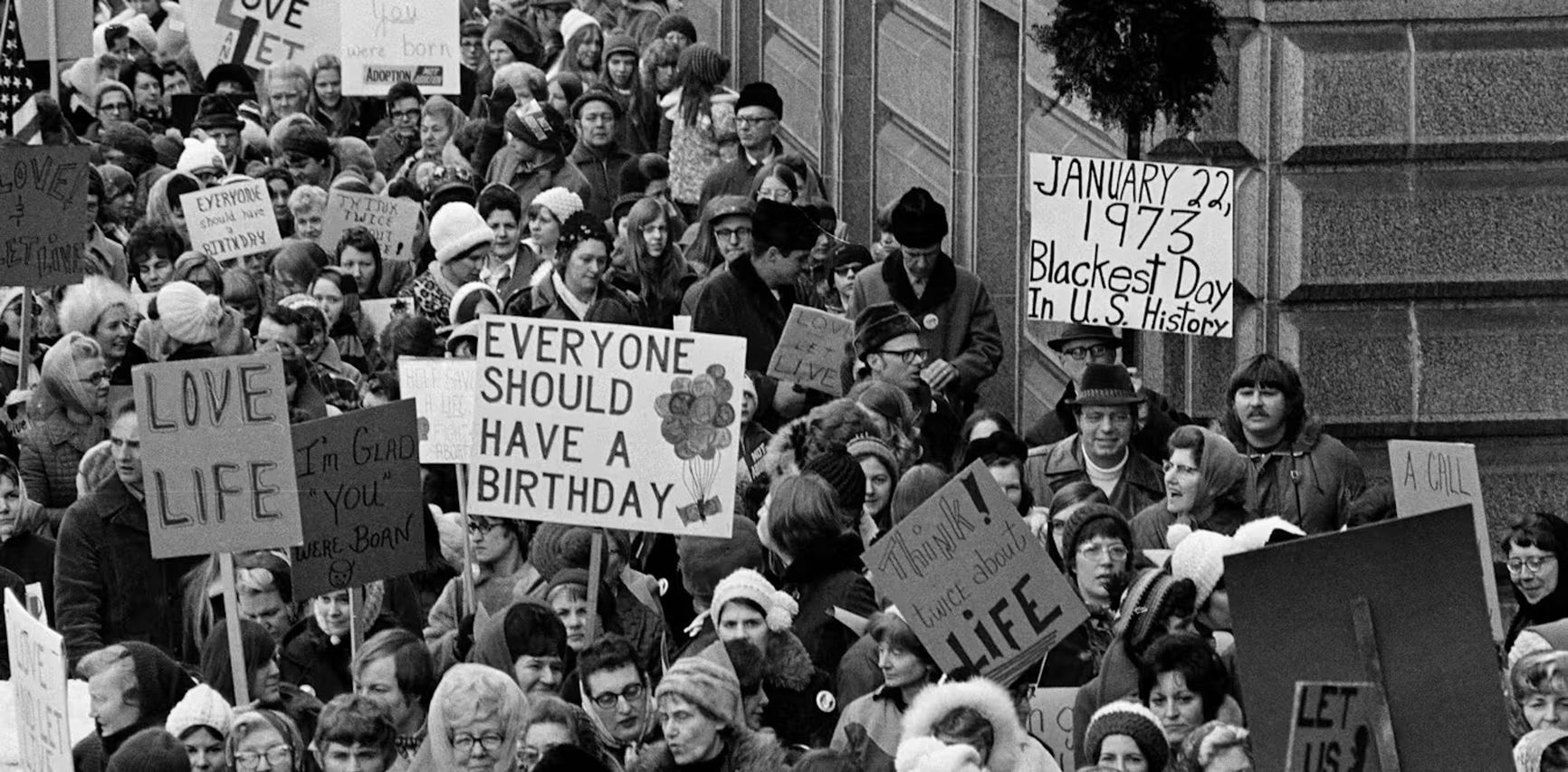

The 1970s made abortion one of the key issues in American domestic politics – and one of the primary topics with which American Catholics became associated in the public consciousness. On January 2, 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court announced its decision in Roe v. Wade, ruling that the constitutional right to privacy prohibits government interference in a woman's “right” to have an abortion.

Pro-life rally in Minnesota following Roe v. Wade drew over 5,000 participants, 1973

AP Photo

The Catholic Church opposed this decision, and many Catholic American activists soon joined the pro-life movement – but far from all. When the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022, returning the regulation of abortion rights from the federal to the state level, the partisan divide among American Catholics was on full display.

The views of the so-called liberals and conservatives within the Catholic Church also diverged on the issue of LGBT+ rights. After the arrest of demonstrators at the Stonewall Inn in New York in 1969, the gay community began an active struggle for its legal and social rights. In 1973, the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its list of mental disorders. Some American Catholics even began developing an interest in LGBT theology, which seeks to explore LGBT+ identity within the framework of Catholic teaching. Others, however, firmly rejected any attempt to move away from the Church’s traditional view of love and marriage as a union exclusively between a man and a woman.

The women’s rights movement also had an impact on the Catholic Church, which was becoming increasingly internally divided. Some clung to ultra-traditional positions: rejection of contraception, support for traditional family roles, opposition to women’s ordination. A progressive wing supported ordaining female priests, accepting childlessness as a valid way of life, adapting to new family structures, and adhering to the “my body, my choice” principle. Meanwhile, those seeking a middle ground remained open to the conditional acceptance of contraception, abortion in certain cases, a more equal distribution of family responsibilities, and greater female participation in Church life.

Lynn Kinlan of Guilderland, New York, poses for a portrait before her ordination ceremony as a Roman Catholic priest at a Unitarian church on Saturday, September 8, 2018, in Albany, New York

Hans Pennink / Times Union

This was the long road that brought American Catholics to the heights of power in the U.S., while also leading to their core dilemma: Can one be both a good Catholic and a good American? The foundations of American identity are the beliefs in unlimited individualism and personal freedom, and a reverence for individual success. The foundations of Catholicism – and Christianity more broadly – are belief in Jesus Christ as a unique “bridge” between the human and the divine, and the fulfillment of human life through communion with God.

It seems that American values have won out. According to opinion polls conducted shortly before the election of the new Pope, American Catholics generally hold quite liberal views on most issues: 84% supported the use of contraception; 83% supported the right to in vitro fertilization (IVF); 63% were opposed to celibacy for clergy; and 59% supported the right of women to become priests.

In addition, 60% of American Catholics believed the Church should be more inclusive, even at the cost of changing its traditional teachings. An even greater share – 70% – supported the right to same-sex marriage, while 59% wanted abortion to be legalized in all or most cases. At the same time, paradoxically, two-thirds of American Catholics considered themselves more conservative than liberal.

A new Pope: yours or ours?

On May 8, when the papal conclave ended with the election of the first-ever Pope from the United States, global media were filled with surprised – and sometimes awed – reactions.

“We'll see what he does, but first of all, it’s just unbelievable – we have an American Pope!”

“And we were told there could never be a Pope from a global superpower!”

While Catholics in St. Peter’s Square and around the world were still celebrating the new Pope’s first public address, commentators were already wondering: what kind of Pope will he be, and how might he differ from his predecessor, Pope Francis?

The previous pontificate was marked by concessions to more progressive Catholics while maintaining the core teachings of the Church. For example, Pope Francis allowed for the blessing of same-sex couples, but upheld the traditional Catholic doctrine that marriage is between a man and a woman.

Though he also commissioned a study on the possibility of ordaining women as deacons (a lower tier of clergy), his public statements and actions made clear he wasn’t enthusiastic about granting them full priesthood. Instead, he aimed to enhance the role of women in the Church through more active participation by laywomen and appointments to key positions in the Vatican.

In the U.S., Pope Francis was popular – 76% of American Catholics approved of his leadership. However, the same poll, conducted between Francis’s death and the election of Leo XIV, showed that although 42% hoped the next Pope would continue Francis’s course, 37% wanted more conservative leadership, and 21% preferred an even more progressive approach.

American Catholics immediately began trying to figure out whether the new Pope would be a “leftist” or a “right-winger.” The list of issues on which he would be judged reflected the full range of concerns in American society: LGBT+ rights, abortion, the traditional family, women’s rights and contraception, immigration, poverty, inclusivity in the Church, and environmental issues.

Many also tried to determine the new Pope’s stance on Trump and J.D. Vance. It was claimed that an X (Twitter) account registered under Robert Prevost’s name had previously reposted articles and tweets critical of the immigration policies that Trump andVance (who converted to Catholicism in 2019) have adopted. However, efforts to clearly label the new Pope as “ours” or “theirs” failed.

The first signals a new pope gives the world regarding his approach comes from the papal name he chooses and the vestments he wears during his first public appearance. In 2013, Jorge Mario Bergoglio chose the name Francis (after St. Francis of Assisi) and wore a simple white garment – sending a clear symbolic message to Catholics about his desire to renew the Church, help the poor, and care for the environment.

The name Francis had never been used by a pontiff before, and this was meant to symbolise a fresh start in the life of Catholicism. In the case of Francis’s successor, the choice of the name Leo XIV alludes to Pope Leo XIII, who in 1891 published the famous encyclical Rerum Novarum. In it, the Pope recognised the right of workers to form labor unions and to receive fair wages, and called on the state to protect the rights of the disadvantaged.

AP Photo / Alessandra Tarantino

For progressive U.S. Catholics, Pope Leo’s choice of name was a sign that, like Francis, he would continue to care for the poor and the oppressed, and that he would pay close attention to developing nations. But the choice also worked as a signal to more conservative Catholics — first, because it symbolised continuity with older traditions, and second, because for Catholics leaning toward the Republican Party, Pope Leo XIII was known for condemning socialism and communism in his Rerum Novarum encyclical, where he characterized such movements as misguided solutions to poverty while affirming the importance of private property.

The fact that the new pope chose traditional papal vestments for his first public appearance was also received positively by many U.S. conservatives, who had disliked Pope Francis’s modest public image and his constant emphasis on personal humility.

Pope Leo XIV later explained his choice: “Pope Leo XIII, in Rerum Novarum, addressed the social question in the context of the first great industrial revolution. Today, the Church offers to all the treasury of its social teaching in response to a new industrial revolution and the developments in artificial intelligence…”

Though Pope Leo XIV was born in Chicago and grew up in the city’s suburbs, he spent decades working on a spiritual mission in Peru, and from 2015 to 2023 served as the bishop of Chiclayo. He is also a Peruvian citizen. This may explain why, despite some widespread antipathy toward the US in parts of the Church (especially in the Global South and in parts of Europe), a U.S.-born pontiff was still considered – and, ultimately, elected.

This background is particularly relevant at a time when Trump’s second administration is pushing “America First” slogans, isolationist policies, and a vision of American exceptionalism. For liberal Catholics, Pope Leo’s Latin American connection felt like a sign of continuity with Pope Francis – the first pope from Latin America. Some hoped that Leo, being American-born, might understand his homeland better than the Argentinian Francis, and could “build bridges” between different groups within American society.

Some progressive U.S. media outlets noted that the world’s two most influential people are now Americans – President Trump and Pope Leo XIV – and that the new pope could serve as a “counterweight to Trumpism.” They emphasised his international experience and concern for ecological issues.

U.S. media noted that the world’s two most influential people are now Americans: President Trump and Pope Leo XIV

Father James Martin, a well-known American priest with progressive views on LGBTQ+ issues, said on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert: “President Trump and Vice President Vance can no longer say the pope doesn’t understand America and therefore we can ignore him… He won’t be afraid to speak his mind.”

Key issues shaping perceptions of Pope Leo include abortion and LGBTQ+ rights. Soon after his election, earlier remarks he had made about homosexuality resurfaced in U.S. media, sparking negative reactions from some Catholic LGBTQ+ organisations. Francis DeBernardo, Executive Director of New Ways Ministry, expressed disappointment upon learning that in 2012, Pope Leo told fellow bishops he regretted that Western media and popular culture promote “sympathy for beliefs and practices contrary to the Gospel, including the homosexual lifestyle and alternative families made up of same-sex partners and their adopted children.”

On May 16, addressing diplomats accredited to the Holy See, the new pope reaffirmed the Church’s position on marriage and abortion. Marriage, he said, is a union “between a man and a woman,” and the unborn child has human dignity.

That was enough for some Catholic Democrats to label him a “conservative” – or even to say that Leo XIV would be a “reactionary” who would reverse the course set by Pope Francis. At the same time, his position on same-sex marriage and abortion pleased many center-right Catholics, whose main objections to the Democratic Party and “progressives” revolve around LGBT+, family, and abortion issues, not climate, immigration, or attitudes to Trump. For America’s highly active pro-life movement, the new pope’s stance was also critically important.

A post on X by Lila Rose, American activist and founder of the prominent pro-life group Live Action:

Later, Pope Leo closed out the major Catholic event Jubilee of Families, Children, Grandparents, and the Elderly by calling the family “the cradle of love.” He added that “marriage is not an ideal, but a measure of true love between a man and a woman,” and that it provides “an example for children of how one ought to live.”

Still, to some Catholic Republicans with strong Trumpist leanings, Pope Leo is seen as a “woke leftist” – primarily because, like Francis, he is likely to continue criticising Trump-era immigration policies (Francis once called Trump “unchristian” with regards to the issue).

Leo’s older brother, John Prevost, told The New York Times on May 8 that Pope Leo XIV holds moderate political views but is deeply concerned about U.S. immigration policy. He added: “I don’t think he’ll stay quiet for long if he has something to say... How far he’ll go, that’s an open question. But he certainly won’t sit on his hands. He’s no silent type.”

Indeed, just a week later – on May 16, during the same meeting with diplomats – Pope Leo declared himself “a citizen, descended from immigrants who once also made the choice to emigrate,” and added that no one is “exempt from the responsibility” to respect the dignity of others.

Another signal some conservative Catholics interpreted as “leftist” was the rediscovery of Pope Leo’s support for Pope Francis’s stance on climate change and environmental protection. At the end of 2024, speaking on the worsening global ecological crisis, then-Cardinal Robert Prevost stressed that humanity’s God-given “dominion over nature” should not turn into “tyranny,” warning of the “harmful” consequences of unchecked technological development and reaffirming the Vatican’s commitment to environmental protection.

However, among some American conservatives – including Catholics – concern for the climate is often viewed as “globalist hysteria” aimed at increasing societal control.

More conspiratorially minded Republicans were quick to label the new pope a globalist and a left-wing activist, citing his old tweets about COVID-19. At the time, the future head of the Catholic Church had reposted tweets from the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and the Archbishop of Los Angeles supporting COVID vaccinations. For some, those tweets were enough to brand the new pope a pawn of the “World Economic Forum globalists.”

A post on X by American ultra-right activist and conspiracy theorist Mike Cernovich:

Some of the most conservative Republicans also condemned the new pope for having once retweeted an emotional statement by Democratic Senator Chris Murphy. Murphy had accused his colleagues of inaction following the 2017 Las Vegas mass shooting in which a gunman killed 60 people at the Route 91 country music festival.

Finally, Pope Leo called for a ceasefire in Gaza – a statement welcomed by Democrats and progressive Catholics, but condemned by Trumpist Catholics. The latter often support Israel not out of deep affinity, but because they strongly oppose pro-Palestinian activism, which they associate with the Islamisation of the U.S. and “wokeism.”

Regarding the war in Ukraine, Pope Leo’s statements so far have been vague. However, the Vatican never openly calls for arms deliveries and always advocates for peace. This stance seems to suit both Republican-leaning Catholics – who oppose “dragging” the U.S. into the “Russia-Ukraine conflict” – and also some radically progressive Catholics, who oppose military aid to Ukraine because they believe it prolongs the human suffering resulting from the conflict.

In short, on some issues Leo XIV is a “conservative,” and on others he is a “liberal.” His views are likely to appeal most to moderate Catholics on both the right and left, though both the radical “Trumpists” and “wokeists” will find many causes for disagreement with the American pontiff.

Incidentally, shortly after the new pope was announced, pro-Trump influencer Charlie Kirk posted a screenshot allegedly showing Robert Prevost’s voting record, claiming it proved he was a Republican because he had voted in Republican primaries. However, Reuters pointed out that the post was misleading. In Illinois, where Pope Leo is from, voters are not asked to declare a party affiliation when registering. According to the outlet, the future pope had voted in both Democratic and Republican primaries.

Even here, the new pontiff is neither “ours” nor “theirs.” And that’s exactly what one should expect – after all, while Pope Leo XIV may be American, he is not an American politician. Leo XIV, like any other pope, is the head of the Catholic Church – a Church with a history, traditions, and teachings that long predate modern political movements and parties. As conservative commentator Matt Walsh put it: “I wish the pope were like me – a Republican, a right-wing nationalist. But American political categories don’t fully apply here.”