After the fall of the Assad regime, the Kurds of northern Syria were bracing for a major war — not with the new powers-that-be in Damascus, but with neighboring Turkey. However, on Feb. 27, the head of the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) called on his organization to lay down their arms. The announcement was all the more notable given that the man who made it, Abdullah Ocalan, is serving a life sentence in a Turkish prison. Many Kurds, Turks, and foreign politicians supported Ocalan’s appeal. Kurds across the region have been fighting an armed struggle for their independence for 41 years, and in Turkey, PKK supporters have long been persecuted. As recently as Mar. 19, the opposition mayor of Istanbul, Ekrem Imamoglu, was detained on charges of links with the PKK. After Ocalan's call, the Kurds are ready to agree to give up their fight in exchange for broad autonomy within Turkey, but not everyone believes in the promises the Turkish government is making.

Content

The Kurdish leader's address after years of isolation

The Kurdish resistance

The PKK will lay down their arms, but there's a nuance

Chances of peace?

The Kurdish leader's address after years of isolation

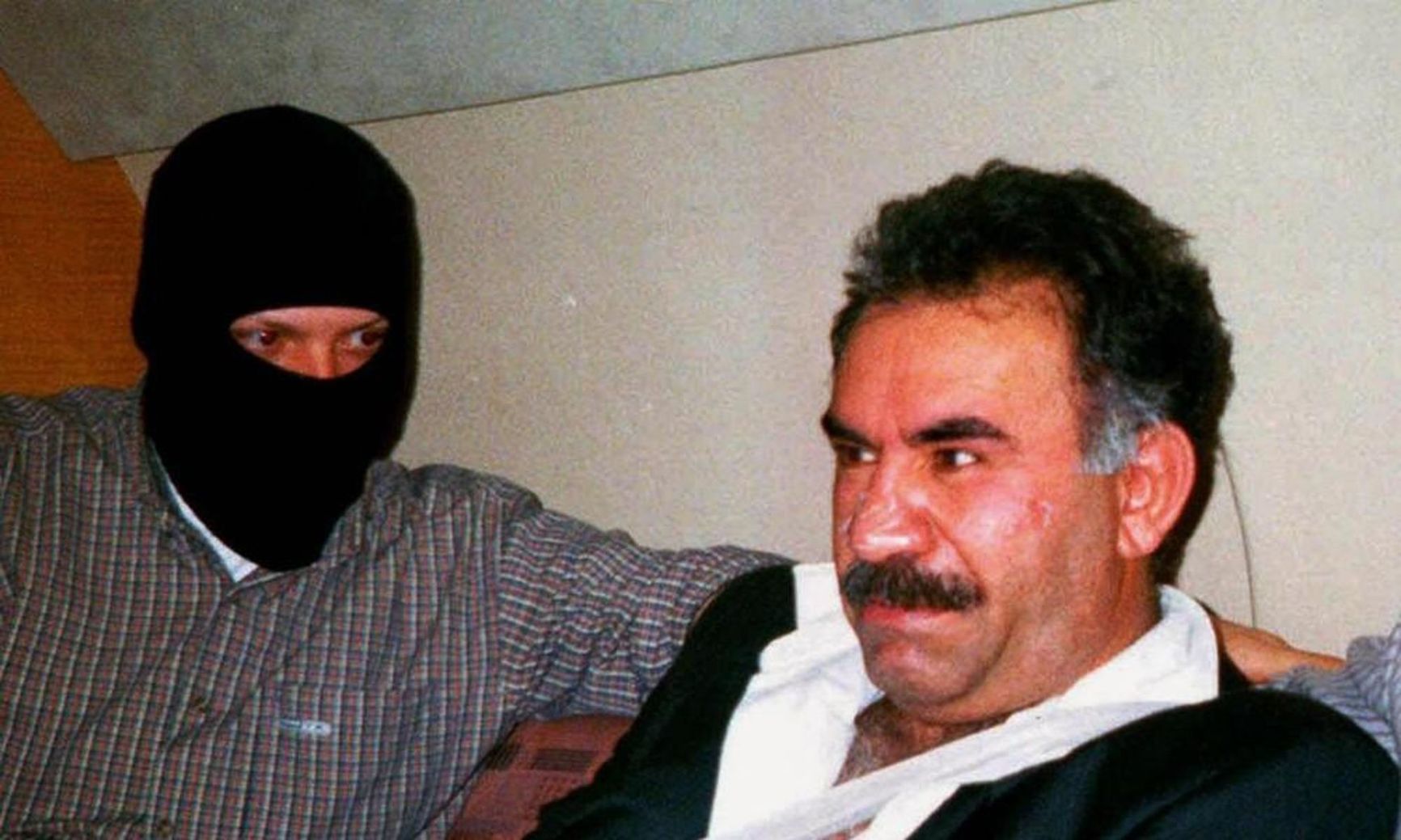

Abdullah Ocalan is Turkey's number one terrorist. He was a wanted man for many years before being arrested on Feb. 15, 1999, by Turkish intelligence — with Russia's direct involvement. A few Kurds, and even some foreigners, protested his detention and death sentence, responding with acts of self-immolation or, more commonly, with chants of “You cannot darken our sun!”

Abdullah Ocalan under arrest, 1999

The PKK interpreted Ocalan's capture as an “international conspiracy against the Kurds.” Several states aided Turkish intelligence and refused to grant asylum to the PKK leader (Russia, in 1998, was among them). Ocalan ended up in Kenya, where he was detained in Nairobi before being extradited to Turkey.

Fearing that the politician might influence the Kurdish liberation movement even from prison, the Turkish authorities isolated him in a facility on the island of Imrali in the Sea of Marmara. Until 2009, he was the only inmate there. The change in Ocalan's position began when Devlet Bahceli, head of the far-right Nationalist Movement Party and one of the PKK's main ideological opponents, addressed Ocalan at a party group meeting in Turkey's Grand National Assembly on Oct. 22, 2024:

“Should the terrorist leader's isolation be lifted, let him come and address the Grand National Assembly of Türkiye. Let him announce that terrorism is finished and that his organization has been disbanded.”

Bahceli's statement signaled openness to negotiation.

After nearly four years of staying incommunicado, Ocalan was allowed a visit by his nephew, Omer Ocalan, a member of the pro-Kurdish Peoples' Equality and Democracy Party (DEM). Public negotiations began, mediated by a DEM delegation of three party members, all of whom boasted a history of multiple arrests as the targets of political persecution. Meanwhile, Ocalan is still denied access to lawyers and family visitation.

The delegation held two meetings with Ocalan in prison before beginning consultations with Turkish parties and representatives of the Kurdish regional government in Iraq. In particular, the delegation traveled to Southern Kurdistan, an autonomous republic within Iraq where the PKK set up its headquarters in the impregnable mountainous region of Qandil. Presumably, the purpose of the DEM representatives’ journey was to deliver Ocalan's message to PKK representatives on the ground in Iraq.

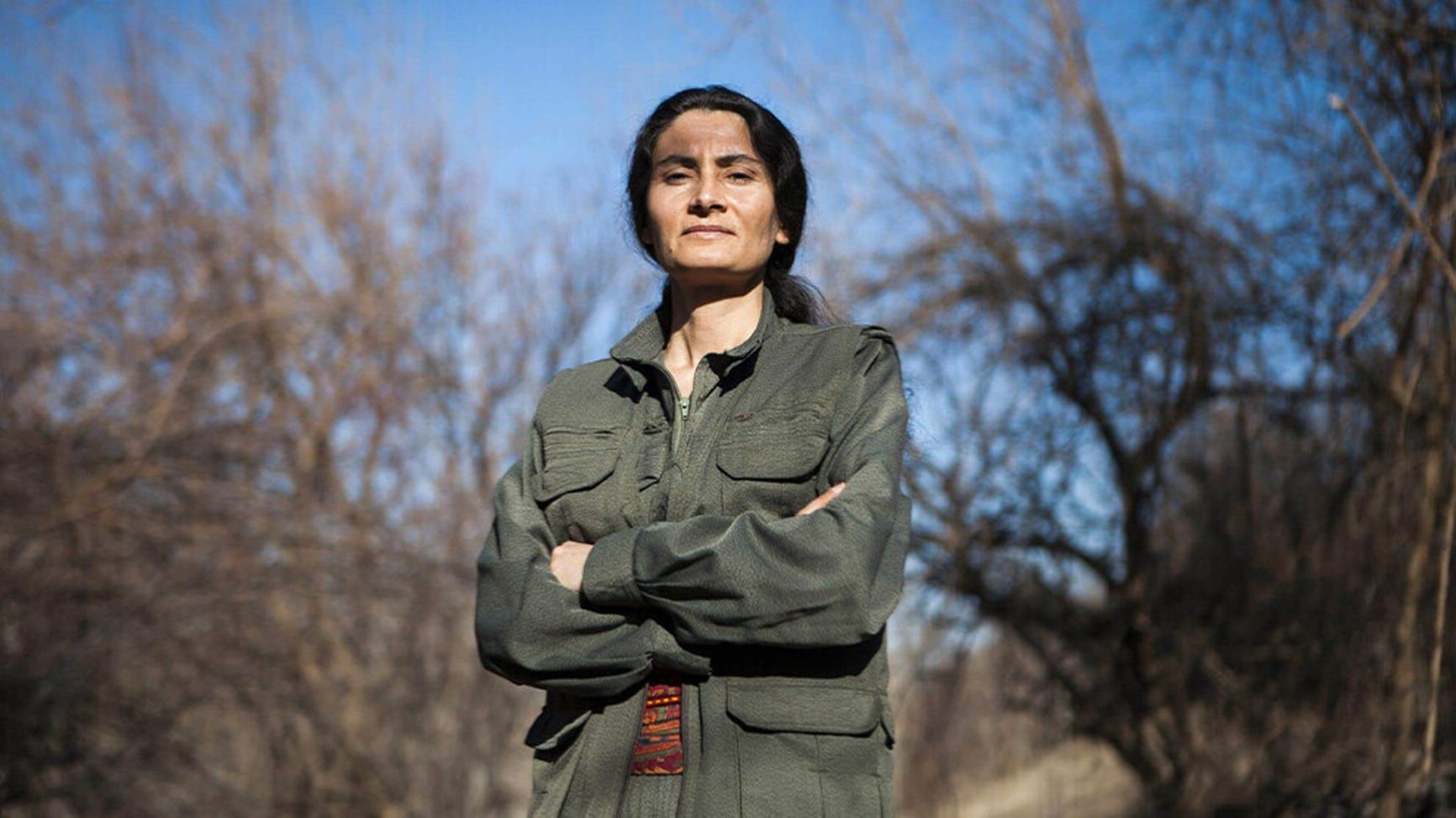

PKK guerrillas, South Kurdistan

Many Kurds welcomed news of Ocalan's address, and crowds gathered to watch it on huge screens that had been set up right on the streets. Bese Hozat, a member of the PKK executive committee and commander of the women's guerrilla units, said on the eve of Ocalan's speech, “We do not accept any other format than a video address.” However, Ocalan never showed his face. Instead, the visiting delegation read out a call for the PKK to lay down its arms and disband. The Kurds did not even hear Ocalan's voice — all they ever saw was a photograph. As a result, not everyone trusts that his call to end the armed struggle is authentic.

Bese Hozat, a member of the PKK's executive committee

In Belgium, one of the few countries that does not recognize the PKK as a terrorist organization, Kurdish party member and former guerrilla Amanos Amed arranged to watch Ocalan's address at a comrade's home. “The Turkish state has banned the video from being shown. The authorities are bullying us again,” Amanos complained.

On the eve of the address, Turkish police made 341 arrests in the Kurdish province of Van on charges of links to the PKK, and a proxy was appointed to run the municipality instead of its elected mayor.

Kurds awaiting Ocalan's address on Feb. 15 in the town of Al Hasakah, northeastern Syria

On the day of Ocalan's anticipated address, several cities in Europe and the Middle East once again saw thousands-strong Kurdish rallies. The protesters' demands were the same: a resolution to the Kurdish issue and freedom for Ocalan. In Germany, where even the PKK flag is banned, Kurds marched from Heilbronn to France's Strasbourg, home to the Council of Europe and the ECHR. Some of the activists were injured in clashes with German police, but the march continued.

A Kurdish march in support of Ocalan and for a solution to the Kurdish issue, Cologne

Tens of thousands of people in northeastern Syria, where Ocalan had long lived and worked, also marched with his portraits and PKK flags. Meanwhile, the Turkish province of Sanliurfa — the homeland of Ocalan and the PKK — had no large-scale protests. This did not come as a surprise, as in Turkey, even suspicion of sympathizing with Ocalan is enough for the authorities to lock up a political opponent for years. Hundreds of people are regularly arrested on allegations of justifying terrorism, and it is on charges of links with the PKK that the Erdogan regime imprisons everyone who stands in opposition to his rule: journalists, politicians, and even former presidential candidate Selahattin Demirtas.

An arrest in Turkey

The Kurdish resistance

Where the Khabur River meets the Tigris, the borders of three states — Turkey, Syria, and Iraq — also meet. A high fence has been built along the entire border between northeastern Syria and Turkey. Locals warn that snipers are active from the Turkish side. In the early 1980s, when the PKK's guerrilla units emerged, Turkey's borders with Syria were not difficult to cross. It was here that a few Kurds began plotting the PKK's attacks on the Turkish army, the first of which occurred on Aug. 15, 1984.

The Insider spoke with a participant in those events, former PKK guerrilla Sary Hussein from a village near Turkey's Mardin. As Hussein recalls it, PKK commander Mahsum Korkmaz was asking his fighters if anyone had relatives in Syria, and Hussein had a brother in the town of Qamishli. Korkmaz decided to move there and set up a safehouse for PKK guerrillas in his brother's home, and then build houses of clay for fighters while awaiting orders from their leader, Abdullah Ocalan. Hussein agreed to this plan, shared it with his young wife Cicek, and they both joined the party. When everything was ready, three groups of 30 or so guerrillas with old machine guns set out to conquer the impregnable mountains.

“We were called adventurers. ‘You don't know the terrain or the region,’ they said. ‘How will you organize supplies of rations and weapons?’ Everyone said so, even some of our comrades. It was like we were on an airplane, but we didn't know where we were going,” explains Sary Hussein. During the first offensive, one of the groups did not dare open fire on Turkish troops. According to Hussein, the unit’s commander turned out to be an agent of the Turkish government.

Sary Hussein today

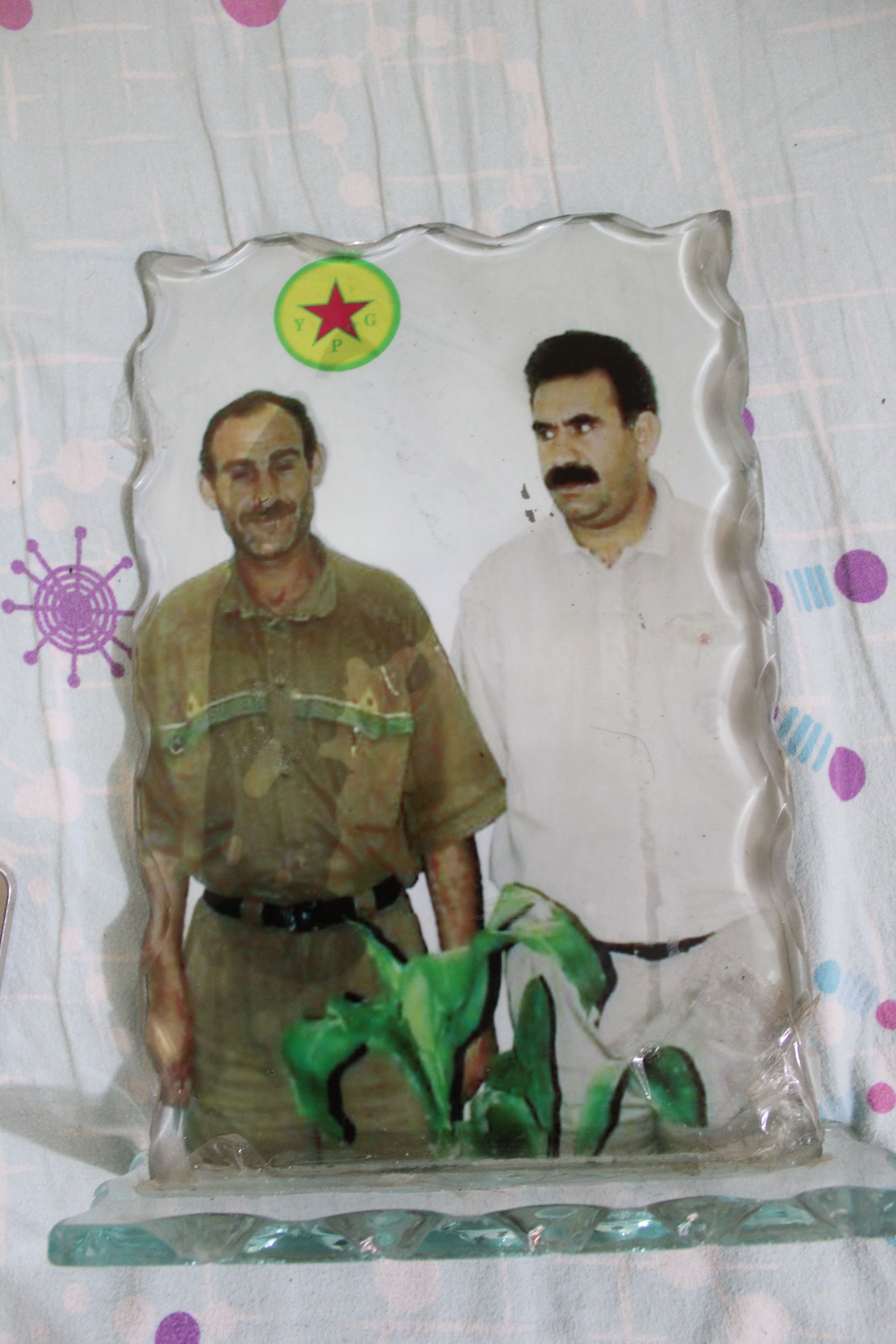

Portraits of the PKK leader are a frequent sight in any Kurdish home, both in Syria and Turkey, and Hussein’s is no exception. The former guerrilla smokes a lot and asks that his interlocutor take a picture of his old portrait with a young Abdullah Ocalan. Ocalan's portraits also hang on the wall in the living room and in his daughters' room.

One of Sary Hussein's daughters joined the party and is now in the mountains of Southern Kurdistan fighting the Turkish army. Her parents have no contact with her — those are the rules. The family remains devoted to the Kurdish cause, and Ocalan's appeal did not come as a shock. “The leader did what he was asked to do: he made the call. Now it's up to Turkey. And this is Turkey's last chance,” Sary Hussein said confidently.

Photo: Sary Hussein as a young man next to Ocalan

The PKK will lay down their arms, but there's a nuance

The Kurds are divided over the appeal of the PKK's founder, who has been behind bars for 26 years. “We will not lay down our arms,” outraged users with Kurdish names wrote online. They are not convinced that Ocalan's call to dissolve the party was authentic: “Does the leader not have a mouth and tongue? Why isn't he making a live statement?” Others, however, believe the word of the Kurdish politicians who visited Ocalan.

PKK guerrillas

Earlier, PKK executive committee member Cemil Bayik said that the DEM party delegation had handed over three letters from Ocalan: one to the guerrilla command in the mountains, one to representatives of the pro-Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces in northeastern Syria (Rojava in Kurdish), and one to PKK members in Europe. None of the recipients were surprised by Ocalan's call. In October, after the delegation's first visit to the prison on Imrali, Ocalan said: “I have a theoretical and practical opportunity to transform the conflict from armed violence to a legal and political struggle.”

Even before the photo of the aging Kurdish leader appeared on the big screens, PKK executive committee member Duran Kalkan said the party would not lay down its arms until Ocalan was released. The PKK reiterated the demand in its announcement of a unilateral ceasefire. Needless to say, Ocalan has not been released — his isolation has not even been eased. According to the PKK, Ocalan's lawyers and family are still not allowed to visit him, and the other four inmates kept in the same prison as Ocalan share his fate. One of them, Veysi Aktas, has served his sentence but remains in prison. Some Kurds believe the authorities want to prevent Aktas from passing on Ocalan's true message.

Another, more radical condition of the PKK is the Turkish authorities' acceptance of Ocalan's political project. The PKK leader proposed the concept of “democratic confederalism,” which would oblige the Kurds to renounce their aspirations for the creation of an independent Kurdistan in exchange for autonomy and self-government inside Turkey. “This means that all municipalities should be under the control of the people, not proxies from Ankara. It has to end once and for all,” Amanos explains.

The policy of appointing “proxies” as mayors of Turkey's predominantly Kurdish cities began in 2016. Meanwhile, elected mayors have faced charges of spreading terrorist propaganda and of maintaining links to the PKK. In October 2024, after negotiations with Ocalan had begun, the mayor of Istanbul's Esenyurt district, Ahmet Özer of the main opposition Republican People's Party (CHP), was arrested. He too was accused of being a member of the PKK.

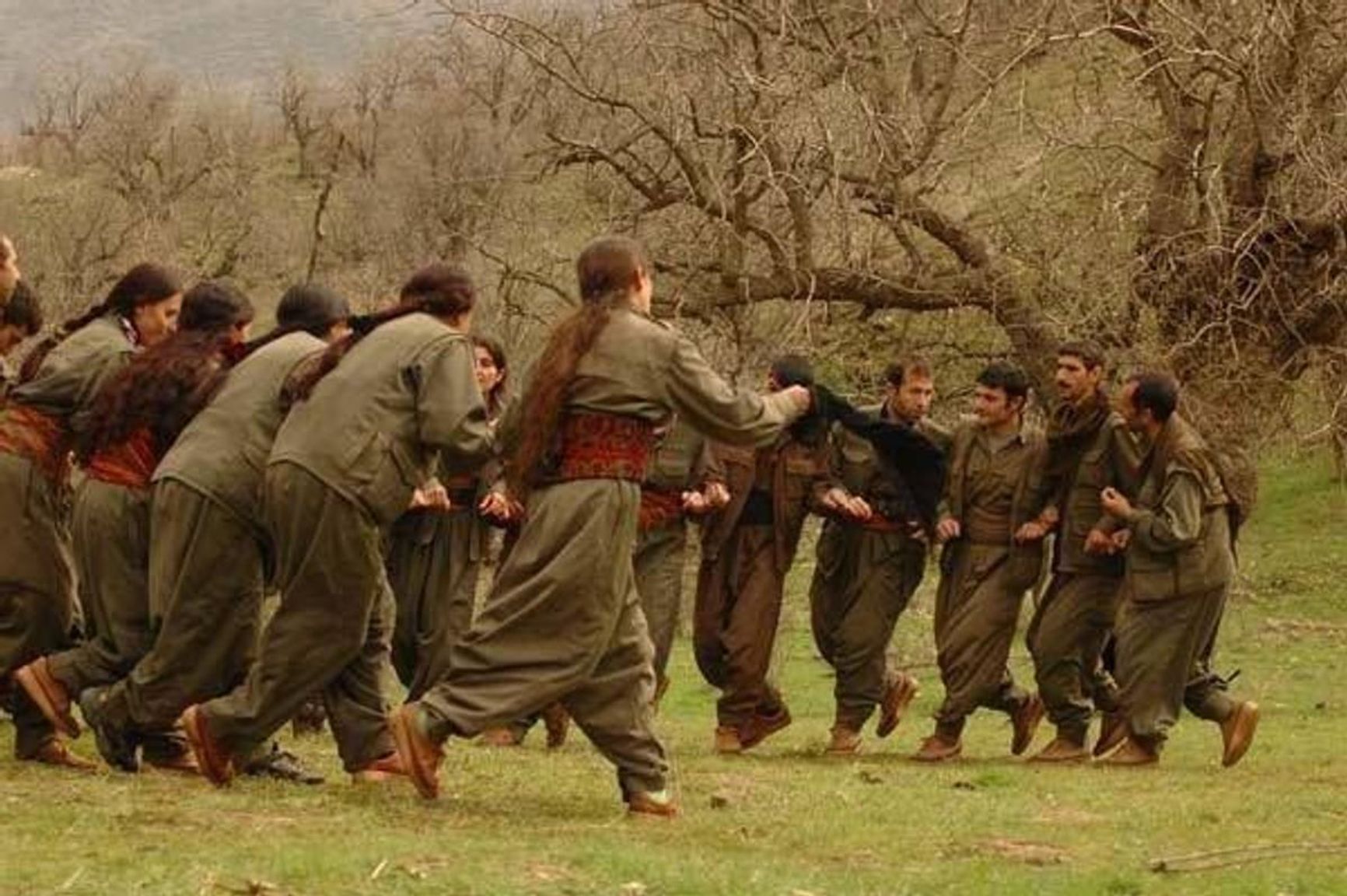

The PKK considers ending anti-Kurdish policies to be another imperative. Turkish officials have publicly maintained contact with some Kurdish politicians and stated that their target is only terrorists, but targeted arrests of ethnic Kurds for demonstrating their national identity have continued. For example, in July 2024, people were detained in Istanbul for performing the traditional Kurdish halay dance at a wedding. The court ordered 11 of them to remain in custody on charges of propaganda for a terrorist organization, while the rest were released under judicial control.

The arrest at the Kurdish wedding in Istanbul

“All changes regarding the Kurdish people and identity should be enshrined in the constitution,” said PKK member Amanos. “Turkey cannot be a country of one people, one language, and one religion. It's an ultimatum. This policy of oppression must be ended once and for all.”

Ocalan has called for the organization of a PKK congress. That would take several months to organize and require third-party mediation, Amanos said. Duran Kalkan, a member of the PKK's executive board, also stated that rapid change is impossible. “Even assuming that the Turkish state takes steps toward peace, the PKK will not be able to ensure its disarmament within a few days. The PKK is tens of thousands of people who know their way around weapons. And they're not mercenaries. Their only driver is a thirst for freedom. No matter how long I have lived in a European city, I am always ready to grab an assault rifle and go to the mountains. It's a skill you can't unlearn,” Amanos smiles.

Chances of peace?

In 2013, a previous PKK attempt to reconcile with Turkey failed. “During the last ceasefire, many of us couldn't even imagine what our movement would have accomplished by now,” Amanos says.

Turkish soldiers in Kurdistan, Northern Iraq

In November 2015, Turkey officially stated that the main threat to national security is the PKK, not ISIS.

In 2015, Turkey stated that the main threat to national security was the PKK, not ISIS

In 2018, due to Turkish pressure on Iraq, the PKK withdrew its forces from Sinjar — where it had been fighting ISIS in order to protect Yazidis — and from the Makhmour refugee camp in Iraq. While Turkish drones in these areas are reportedly still attacking PKK supporters, the areas are officially controlled by local self-defense militias. The guerrillas make extensive use of tunnels and sometimes even deploy drones of their own to attack Turkish bases. Their every statement concludes with the slogan “Bijî Serok Apo,” the Kurdish for “Long live leader Apo,” and protesters carry portraits of Abdullah Ocalan and PKK flags. Militias loyal to the Kurdish liberation movement, as well as PKK-allied Turkish left-wing groups in the United Peoples' Revolutionary Movement coalition, report attacks on police and regime supporters almost monthly.

PKK guerrillas perform a Kurdish folk dance

Recent changes in the balance of power in the Middle East — the coup in Syria, the weakening of Iranian influence, and the deepening economic crisis in Turkey itself — have provided an incentive to accelerate the resolution of the conflict between the Turkish state and the Kurds.

Shortly after Ocalan's call, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan confirmed that a new era had begun. Erdogan emphasized, however, that “In our constitution, the first four articles remain and we continue on our path.” The third article of the Turkish constitution says that the Turkish state is one, inseparable from its territory and nation, and that its official language is Turkish. These words of the Turkish president mean that it is too early to hope for the inclusion of Kurds and the Kurdish language in the country's founding document.

Ozgur Özel, leader of the opposition People's Republican Party, asked the Turkish president to be “honest and open” and said the responsibility for peace lies on both sides. Supporters of Erdogan's Justice and Development Party (AKP) have voiced support for a possible peace. “We have lost 40,000 lives to terrorism. Five million people were displaced from their homes. 'Turkey without terror' doesn't just mean 'peace.' It means 'a great Turkey,'” writes Turkish journalist Hasan Basri Akdemir.

When the war is over, Amanos wants to come to his native Amed — to see his family, walk the streets where he once fought the police and military, and build a house. Yet Amanos realizes his dreams might have to wait: “Even if peace comes tomorrow and our leader Ocalan is released from prison, I will wait a few years before returning. I don't trust the Turkish government. None of us do.”