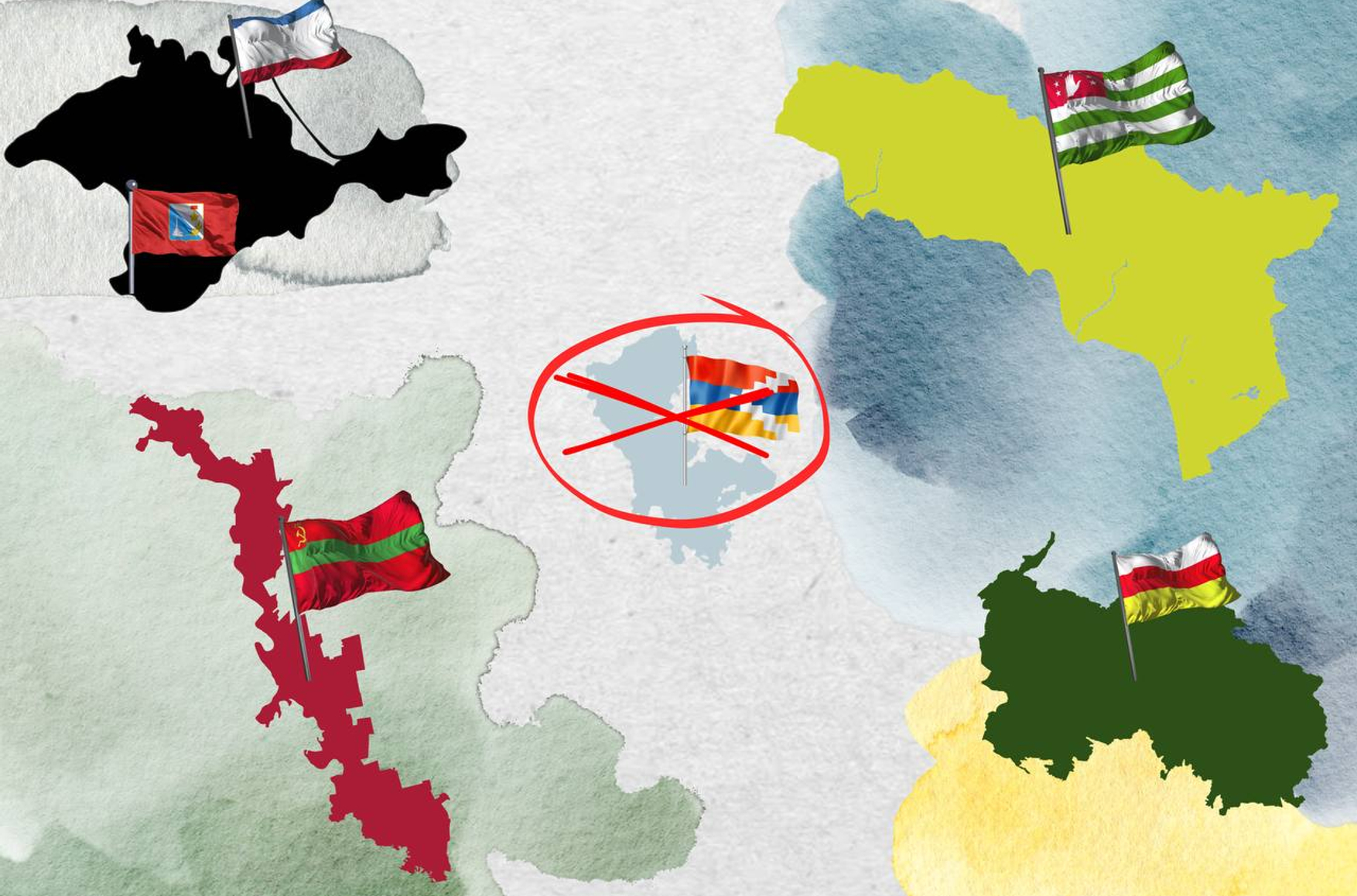

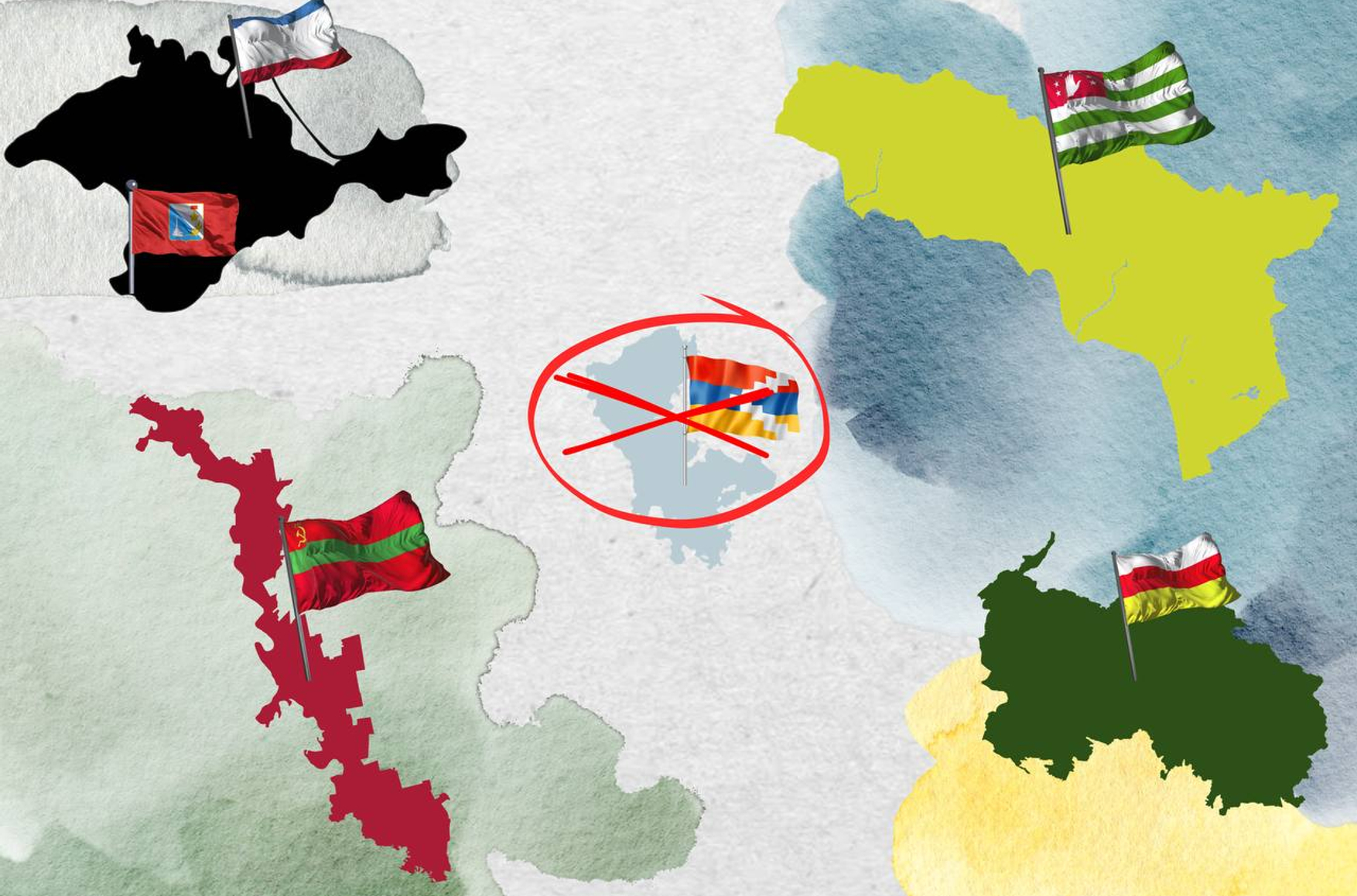

The Azerbaijani military's takeover of Karabakh marks more than just the resolution of an age-old “frozen” armed strife and territorial disagreement. Effectively, it is a unilateral, forceful dissolution of an unrecognized yet well-established state formation that endured for over three decades. This event seems to set a significant precedent with extensive implications, not only for the former USSR region but beyond. Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine have been keenly observing the Karabakh precedent and how the international community absorbed it. While discussions about a military course of action are reluctantly engaged in Georgia and Moldova, there is serious consideration of Crimea's potential return following a similar Karabakh-esque scenario.

Content

Nagorno-Karabakh: Russia takes a back seat

Transnistria: Balancing between the Cypriot and Karabakh models

Abkhazia and South Ossetia: “Georgia must not engage in military aggression under any circumstances”

Crimea and Sevastopol: “We need to offer the population something better than rebels and separatists”

Nagorno-Karabakh: Russia takes a back seat

No matter how acerbic Russian propaganda may be, the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict was resolved, defying Russian expectations and strategies. The Kremlin found itself sidelined and impotent, a role reversal that undoubtedly chips away at Russia's influence both within the region and on the global stage. Several groundbreaking aspects underscore this historic event:

- For the first time, a post-Soviet “parent” state has reinstated lost territorial integrity through force, bypassing the protracted and painful “pacification” process, such as the integration of Chechnya into the Russian Federation.

- Stepping out of the spotlight for the first time, Russia yielded its traditional role to another regional powerhouse—Turkey, which has supported Azerbaijan for years in its struggle against Armenia.

- For the first time agreements defining Russia's role in the conflict zone were openly breached without opposition from Moscow. This included the freedom of movement through the Lachin corridor , a responsibility previously overseen by Russian peacekeepers.

- For the first time a conflict saw a unilateral capitulation of nominally separatist forces, dismantling of their state institutions, and a mass exodus of the majority of the population, all met with silent consent from Russia and the global community.

- For the first time, action affirmed the principle of upholding Soviet-era administrative borders, now transformed into boundaries between independent nations, trumping the rights of ethnic minorities to self-determination.

Against a backdrop of Russia's diminishing military, political, and economic clout, exacerbated by its involvement in the Ukrainian conflict, the Karabakh development is set to reshape the security dynamics in the Caucasus. Its ripple effect is expected to influence other territorial disputes involving Russia, such as Transnistria, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia, as well as the Crimean Peninsula.

Transnistria: Balancing between the Cypriot and Karabakh models

At first glance, the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR) bears a striking resemblance to Nagorno-Karabakh. This entity emerged from an armed conflict during the dissolution of the USSR, with a relatively small population, complete dependence on external support from its patron state—Russia—and effectively under its military protectorate.

In PMR, similar to Nagorno-Karabakh, there is a Russian peacekeeping presence. Likewise, as in the Karabakh case, no one, including Russia, recognizes Transnistria's independence. Much like Karabakh, Transnistria could be relatively easily isolated from the outside world through joint efforts of Moldova and Ukraine. Just as Azerbaijan relied on external players' support, notably Turkey, in planning the operation to bring Nagorno-Karabakh under its control, Moldova could theoretically count on Ukraine's support and that of NATO countries.

A six-kilometer mountainous corridor connecting Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, located in the Lachin district of Azerbaijan.

However, differences emerge beyond this point. Unlike Azerbaijan, Moldova lacks any significant military resources or means for a long-term Armed Forces development program. Moldova strictly advocates a peaceful path for the reintegration of the seceded region. Most importantly, the PMR has close economic ties with Moldova and the EU, with over 70% of Transnistria's population holding Moldovan passports.

Victor Ciobanu, Moldovan political analyst:

“I would refrain from drawing a parallel with the recent events in Karabakh, let alone using it as a model. While the temptation does exist, especially from fervently patriotic stances, the similarities between frozen conflicts within the former USSR—centering on the creation of separatist enclaves by the imperial center to retain influence and destabilize ex-Soviet nations—only go so far.

There will be no use of force to resolve the conflict, and this is the consistent official position of Chisinau. Even when the Ukrainian leadership suggested 'taking Transnistria in three days,' provided that Moldova would request Ukraine's assistance, such a request was not made, and the official position of Chisinau remained unchanged.”

A six-kilometer mountainous corridor connecting Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, located in the Lachin district of Azerbaijan.

There will be no use of force to resolve the conflict, and this is the consistent official position of Chisinau

Moldova is steadfast in its commitment to resolving the Transnistrian conflict through peaceful means. This resolution is expected to come after the conclusion of the ongoing war, Ukraine's victory, and the withdrawal of Russian troops from Transnistrian territory. Remarkably, Moldova could potentially secure EU membership by 2030, even if the conflict remains unresolved. This insight was shared by the European Union's High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Josep Borrell.

In this scenario, if the Republic of Moldova does not join the EU as a fully reintegrated nation, the authorities in Chisinau, in collaboration with international partners, will continue to seek solutions for the Transnistrian conflict, even post-EU accession. Speaking in terms of analogies and models, Moldova is more likely to follow the Cypriot model rather than the Karabakh model.

Alexei Tulbure, Director of the Institute of Oral History of Moldova and former Ambassador, Permanent Representative of Moldova to the United Nations:

“I wouldn't draw a direct or explicit correlation between the events in Nagorno-Karabakh and Transnistria. However, there is a common denominator—Russia's position. It's evident that the resolution in Nagorno-Karabakh, as it unfolded, is a consequence of the metamorphoses occurring within Russia, its weakening, and its failure to fulfill its obligations as a guarantor and mediator in this conflict.

Yes, the Transnistrian conflict is currently at its most opportune point for resolution. There have even been proposals from Kyiv for a forceful resolution by exerting pressure from Kyiv and Chisinau on Tiraspol. The challenge lies in the fact that after resolving the conflict, the territory needs to be integrated, involving half a million inhabitants who have lived in an entirely different reality. Laws and norms need to be aligned with those on the right bank of the Dniester. Moldova lacks these resources, but they are available in the West. Therefore, the resolution of the Transnistrian conflict needs to be coordinated, including with Western partners who will actively participate in this conflict.

The final resolution of the conflict will occur when Russia is significantly weakened. I'm not referring to a defeat in war because the conflict is prolonged, but Russia's weakening will continue until it can no longer significantly influence the region. Currently, Russia's impact is very weak, and it cannot support Transnistria as it has over the last 30 years. Furthermore, Ukraine serves as a buffer between Russia and Transnistria. For Transnistria, this acts as an obstacle to interacting with the Kremlin.

A six-kilometer mountainous corridor connecting Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, located in the Lachin district of Azerbaijan.

The final resolution of the conflict will occur when Russia is significantly weakened

In 2024, the agreement between Ukraine and Russia on the transit of gas through the trans-Balkan gas pipeline, which supplies gas from Russia to Europe, including Transnistria, is set to expire. If this agreement ends without a new one in place, it can be assumed that gas will no longer flow through this pipeline. This would affect Transnistria, which has relied on this free gas from Russia for the past 30 years, sustaining the region's economy and budget. Without the inflow of gas, Transnistria would become economically unsustainable, leaving the region no choice but to seek other means of survival, including reintegration into Moldova.

Currently, the region operates under Moldova's export customs documents, with its main products being metal, cement, and electricity—all of which are sold to the West through Moldova. Hence, the trajectory is moving towards conflict resolution, expected to be peaceful and political, although within the context of war, there are multiple possibilities. Chisinau maintains the position that all of this should be resolved in cooperation with Tiraspol without resorting to radical measures. A maximum of two years is anticipated for the resolution of the conflict, primarily driven by the fact that the main obstacle to resolution, Russia, will lose its influence in the region.”

Vasily Shova, regional conflict resolution expert and former Advisor to the President of the Republic of Moldova on Reintegration:

“Comparing the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh and the conflict in Moldova solely in terms of the disagreements between Chisinau and Tiraspol is not entirely accurate. We had a small phase of armed conflict at the beginning, but the parties quickly transitioned to a peace process. Since 1993, this process has been ongoing, and we have not had a single real destabilization situation in terms of a possible shift towards a forceful scenario, unlike what happened in Nagorno-Karabakh.

The most important aspect is the roots of the conflict. At the initial stage of negotiations for the political settlement of the conflict, a joint statement was signed involving all parties, affirming that there were no historical, political, ethnic, religious, or other issues between Chisinau and Tiraspol that could hinder finding a peaceful solution to the conflict. As far as I understand, in Karabakh, there is a national, historical, and religious dimension.

Since 1993, we have been resolving issues exclusively through peaceful means. Tens of thousands of people from both banks of the Dniester cross this very bank every day—working, communicating, with mixed families, and children studying. Our conflict is, in essence, peculiar. Why hasn't there been a resolution after two decades? Because there are still discrepancies regarding the political status and economic interests.”

Abkhazia and South Ossetia: “Georgia must not engage in military aggression under any circumstances”

The regions that broke away from Georgia differ from Nagorno-Karabakh in that they are recognized as independent by the patron country—Russia—as well as a few other countries (Nicaragua, Venezuela, Nauru, and Syria). The current status and position of Abkhazia and South Ossetia were established as a result of the war between Georgia and Russia in 2008, rather than processes that took place in the early 1990s amid the collapse of the USSR.

Nonetheless, the swift fall of Karabakh triggered a significant response both in Georgia and in Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Former Georgian President Mikhail Saakashvili wrote that the Karabakh example presents “unique opportunities,” and current Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili, speaking at the UN, appealed to “Abkhaz and Ossetian brothers and sisters” to unite.

A six-kilometer mountainous corridor connecting Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, located in the Lachin district of Azerbaijan.

In response, there have been discussions in Abkhazia about the possibility of joining the union state of Russia and Belarus, and in South Ossetia about the prospects of closer integration with Russia. It's also not ruled out that Turkey might support Georgia's strategy regarding the former autonomies—they have been growing closer in recent times.

Paata Zakareishvili, former Georgian Minister for Reconciliation and Civic Equality:

“What is happening in Azerbaijan since 2020 and in Ukraine demonstrates a common set of problems. The Soviet Union is finally crumbling in Ukraine, and against this backdrop, Russia clearly cannot perform the functions it did in the USSR and the CIS. All post-Soviet countries see this.

There is no idea within the Georgian government to 'regain Abkhazia and South Ossetia.' This question is not discussed at the political level, not even by the most radical parties. We have one party, 'European Georgia,' with about 2-3% support, but even they do not openly talk about it, although they consider the possibility. Apart from them, no one even comes close to this idea because it is toxic and unpopular in society. Georgia has experienced several wars, and any form of armed conflict is absolutely unacceptable to the citizens of Georgia.

A six-kilometer mountainous corridor connecting Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, located in the Lachin district of Azerbaijan.

The idea of regaining Abkhazia and South Ossetia is toxic and unpopular in society

If Georgia chooses the path of closer integration with the EU, the peoples in the territories of the former Abkhazian and South Ossetian autonomous regions have two options.

The first option is that Russia, at any cost, pursues its goals in Ukraine and attempts to retain Abkhazia and South Ossetia, thereby tying Georgia, a country that is currently pro-Russian, to itself. In the end, Russia might annex these regions. However, this is unacceptable for Abkhazia, and they are fighting against it. The question remains how long they can sustain their efforts in terms of time and resources. South Ossetia, on the other hand, is striving to become part of Russia.

The other option is to become a part of Georgia, but exclusively through peaceful means, embracing the values of the EU and NATO. This approach aims to maintain the security of the peoples, strengthen their identity and values, create administrative political guarantees for their self-governance.”

Tornike Sharashenidze, a Georgian political scientist and the head of the School of International Relations at the Georgian Institute of Public Affairs (GIPA):

“The main difference for us is that there were no Russian troops in Nagorno-Karabakh. Moreover, three years ago, Azerbaijan already won the main phase of the war, and it was only a matter of finishing the job.

In this regard, nothing will change for us. Russian troops are present in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, as we know. Russia does not plan to withdraw from there anytime soon. Georgia will definitely not invade. Everyone understands this, including those who said that Georgia would seize the moment, considering that Russia is occupied with Ukraine, and launch an attack. This will not happen because Georgia is focused on resolving its territorial issues peacefully. So, even if Georgia decided to attack to reclaim its rightful territories, it would encounter Russian military. But no one will be committing suicide. We should prepare to resolve the issue of territorial integrity peacefully when the opportunity arises.

A six-kilometer mountainous corridor connecting Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, located in the Lachin district of Azerbaijan.

No one will be committing suicide by attacking Abkhazia and South Ossetia

I am confident that even if there are no Russian troops present at some point, Georgia will attempt to resolve everything peacefully in any case. Saakashvili himself mentioned this at the UN after the 2008 war, and this remains Georgia's official position. Moreover, the current authorities in Georgia pursue a softer policy towards the occupied territories.

In Tbilisi, various plans for reintegration are being developed. It's all on paper, it just needs to be implemented, but something is missing. We need the citizens living there in Sukhumi and Tskhinvali to want to return. At the moment, this is not an easy task, but we need to work in this direction. Of course, the timing also depends on events in Ukraine. We all hope that one fine day, Russia will become a state that communicates gently with its neighbors and respects them.”

Crimea and Sevastopol: “We need to offer the population something better than rebels and separatists”

With the annexation of Crimea and Sevastopol by Russia, things are somewhat more complicated than with the “LNR” and adjacent “new territories.” Both entities de facto did not exist as separatist states. Due to the swift and nearly bloodless integration into Russia in 2014, no separate power structures were formed here, nor did an overtly mafia-like economic system of the Donbass type take shape. Both regions received substantial funds from the Russian budget, and the majority of the population remained loyal to Moscow.

A six-kilometer mountainous corridor connecting Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, located in the Lachin district of Azerbaijan.

Military confrontation bypassed the Crimean Peninsula in 2014, but during the current war, the Ukrainian Armed Forces are gradually implementing a strategy that can be characterized as an attempt to isolate and bring the region under fire control using long-range precision weapons (more details can be found in the extensive report by The Insider). If successful, Crimea and Sevastopol will find themselves in a situation similar to Nagorno-Karabakh during the blockade period, followed by capitulation.

Tamila Tasheva, Deputy Permanent Representative of the President of Ukraine in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea:

“The key for us is to cut off supply chains from Russia to occupied Crimea. The legitimate military targets are military facilities in the territory of Crimea, the Russian fleet in Sevastopol, and the illegal 'Kerch Strait Bridge,' which is effectively the main artery connecting Crimea and the Russian territory. Accordingly, any actions against this bridge affect Russia's military operations in the southern direction. It's no secret that supplies have slowed down, there are issues with manpower being moved there, including difficulties with evacuating the wounded, and so on.

The sentiments of the Crimean population are noteworthy. The population sees what has been happening over the past year—initial missile strikes targeting military facilities, specifically in Novofedorivka in August of last year, then the strikes on the illegal 'Kerch Strait Bridge' in October. All of this cannot but influence the people living in Crimea. They see it and clearly understand and say that this is not just a 'Special Operation,' this is war, we are living in a war. They question the local so-called occupational 'government.' According to our sources, we know that the main emotion currently prevalent among the people in Crimea is fear—not fear of Ukraine shelling them, but fear of speaking up. Fear has always been there since 2014, and now they are afraid to say anything or openly express their opinion.

A six-kilometer mountainous corridor connecting Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, located in the Lachin district of Azerbaijan.

The main emotion currently prevalent among the people in Crimea is fear

“The second point we note in this classified study, which analyzed the attitudes of pro-Russian and pro-Ukrainian populations, is that even pro-Russian citizens say 'we thought Crimea was with Russia forever, but that's not the case, and we understand that Ukraine will liberate Crimea.' Another crucial point we heard in almost all interviews is that the illegal 'Kerch Strait Bridge,' connecting Crimea and Russia, is practically almost the sole symbol of Russia's presence in Crimea, apart from the fleet, of course, and it is the only thing that Russia has actually built, a symbol of Russia. If this bridge is no more, and most likely the Armed Forces of Ukraine will continue to act towards this end, it will signify an ideological failure of the policy Russia is pursuing.

We are developing a policy of reintegration solutions for Crimea. And we continue to insist that we will not persecute any citizens who lived in Crimea before 2014 or were born there based on their residence in the occupied territory. We are preparing steps for the restoration of Ukrainian authority in Crimea, and we already have some developments in this regard. Therefore, we are preparing, of course, for military operations, but we need more support from our international partners.”

Alexey Melnyk, political scientist at the Olexander Razumkov Ukrainian Center for Economic and Political Studies:

“Let's start off by gaining a broader perspective. Taking Transnistria into account, it stands as a landlocked region, enclosed by Ukraine on one side and Moldova on the other. How did it establish its claim to independence? It was not devoid of involvement from both neighboring nations. Smuggling and the trade of energy resources prospered, with attempts to pin the debt on Moldova's budget. If Ukraine and Moldova pursue a specific objective, Transnistria may soon find itself with no option but to declare an end to its existence, akin to Nagorno-Karabakh. Alternatively, a more lenient approach could be taken, preserving the semblance of autonomy.

Crimea follows a somewhat analogous, yet more intricate, situation but on a grander scale. Should the already precarious Crimean Bridge be dismantled, ferries would be the only option left. Two million people cannot be efficiently transported. Crimea was heavily subsidized, 75% under Ukraine and an astounding 90% under Russia. How long will Aksyonov's regime endure? We could present a favorable alternative while maintaining appearances to avert potential unrest.

The British counter-insurgency doctrine is worth noting, given the country's extensive experience in handling insurgents and separatists. A pivotal aspect of this strategy entails authorities offering the territory's populace a superior option to what the insurgents and separatists provide. After a coercive or military phase, presenting an alternative that surpasses the prospect of lingering as an unrecognized, self-proclaimed territory is crucial.”

A six-kilometer mountainous corridor connecting Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, located in the Lachin district of Azerbaijan.

After a coercive or military phase, presenting an alternative that surpasses the prospect of lingering as an unrecognized, self-proclaimed territory is crucial

In successful conflict resolution, there are always essential elements. One of them is the elimination of external destabilizing forces, particularly those invested in perpetuating or escalating frozen conflicts. The second aspect involves the new authority offering the population something better than what was there before.”

A six-kilometer mountainous corridor connecting Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, located in the Lachin district of Azerbaijan.