One of the best-known fighters for Ukrainian independence, Stepan Bandera spent most of the Second World War in a Nazi concentration camp, while German secret services hunted down his associates. However, it is Bandera whom the Soviet and now Putin's propaganda depicts as the most villainous of Hitler’s henchmen. His followers, known as the Banderites, evolved from a mid-20th century insurgent movement to a figment of social imagination, becoming a pretext for Russia's “special military operation” to “de-Nazify” Ukraine. This piece covers the essentials of what there is to know about this historical figure.

Content

What the Banderites fought and died for

Stepan Bandera: the man behind the myth

The Banderites vs. the world

«A stubborn Slav»

There is no telling whether Stepan Bandera would be half as infamous in Russia, had it not been for Russian propaganda, which puts him in the spotlight of every Ukraine-related item. In his homeland, Bandera is perceived as a historical figure and freedom fighter; the original Banderite salute – “Glory to Ukraine! Glory to the heroes!” – has lost all of its nationalist connotations.

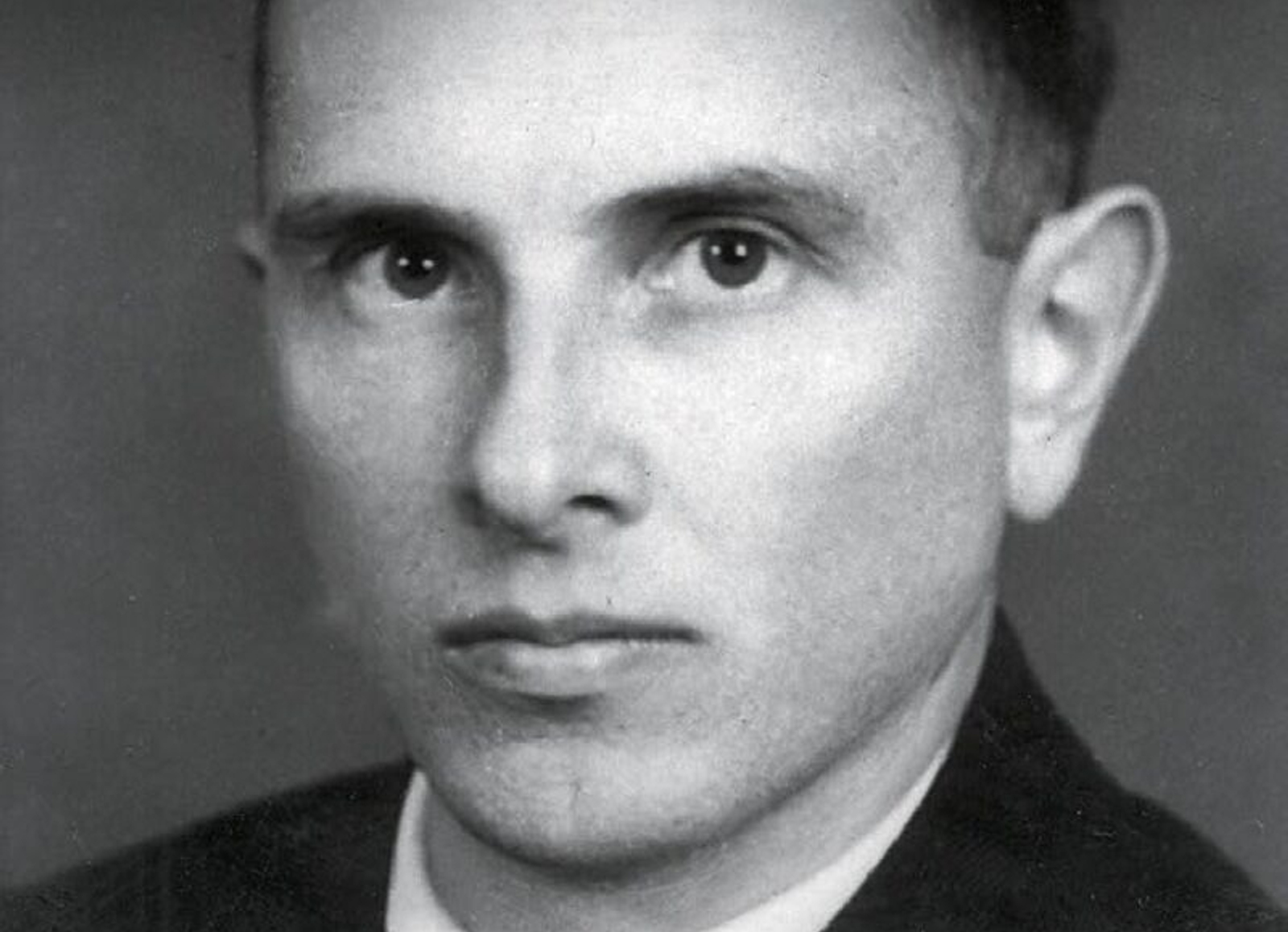

Meanwhile, Russian propagandists keep fostering the myth of Stepan Bandera as being a diehard Nazi. The 14th SS-Volunteer Division «Galicia”, which was formed in Ukraine from local volunteers, is often presented as Bandera’s project, even though neither he nor his followers had anything to do with it. One of the most popular visual representations of Bandera in Russian cyberspace is in fact a photograph of Wehrmacht lieutenant general Reinhard Gehlen, which is used as evidence that Bandera wore “a fascist uniform” and was even awarded “the German cross”. Gehlen and Bandera barely look alike, but the audience of Russian-only social media doesn’t seem to care.

“Stepan Bandera in the middle”: a popular fake photo of Bandera (the man in the photo is Reinhard Gehlen)

What the Banderites fought and died for

Stepan Bandera was a staunch advocate of his country's independence. From its inception, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), where Bandera at some point headed one of the two factions, was far removed from the doctrines employed by German Nazism. The OUN's ideology lacked the core Nazi value: the concept of racial and ethnic supremacy. OUN members never viewed Ukrainians as a “superior race”. All they wanted was independence and freedom from Polish and Russian (or Soviet) control and influence. Authored in 1929 by Stepan Lenkavsky (imprisoned in Auschwitz from 1941 to 1944) and supported by Bandera, “The Ukrainian Nationalist's Decalogue” speaks of “hatred for and uncompromising struggle against” the nation’s enemies and pride for Tryzub (the trident symbol). Its authors call for the creation of a Ukrainian state or perishing in an attempt to do so – but say nothing that would resemble the German Nazis’ racist rhetoric or Italian fascists’ imperial pathos. Importantly, in the eyes of Ukrainian nationalists, Muscovy – used here as an umbrella term for Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union – had inherited the Golden Horde’s tyranny rather than the early forms of democracy typical of Slavic peoples. And yet, despite their perception of Moscow as an “Asiatic” enemy, the Banderites, unlike the Nazis, never took up arms against non-European peoples. A 1950 official publication of the OUN titled Who the Banderites Are, and What They Stand For reads: “We are opposed only to Bolsheviks with imperial ambitions regardless of their social or ethnic origins. It is vile slander that we hate all Soviet people indiscriminately.” Moreover, the Banderites sought to engage Middle Eastern nations in their struggle against the Soviet Union, which was reflected in The Song About an Uzbek: its character, a native of the Middle East, joins the Banderites and falls in an unequal battle in Volhynia. His brothers in arms sing over his grave:

Так знайте ж, що ця ото дивна могила

Союз поневолених кровю окропила

Це ми об’єднали всі віри й народи

В імя боротьби з ворогами свободи.

(So let it be known that this unusual tomb

Bound the union of the enslaved together with blood

It is us, uniting all creeds and peoples

To fight against the enemies of freedom.)

The fight of “all creeds and peoples” against “the enemies of freedom” is the element of Banderite ideology that sets it apart from the clerical and quasi-fascist doctrines and determines its national-democratic nature. The idea of freedom, counterpoised to imperial narratives of supremacy, favored the OUN's rapid evolution. In1958, when Bandera lived in West Germany as an emigrant, he characterized the Second World War as a clash between two “totalitarian predatory regimes”, Hitlerism and Stalinism: the clash OUN activists had leveraged as best they could to secure Ukraine's future independence. In the 21st century, we are witnessing a further evolution of Bandera’s political project, which keeps distancing itself from its conservative origins and is undergoing historical change. Many modern-day Banderites are Russian-speaking and perceive Russian statehood not only as an external colonial force but also as a form of internal dictatorship, which has forced historical Slavic identities and phenomena, including the Russian language, into autocracy, a foreign and repressive form of existence.

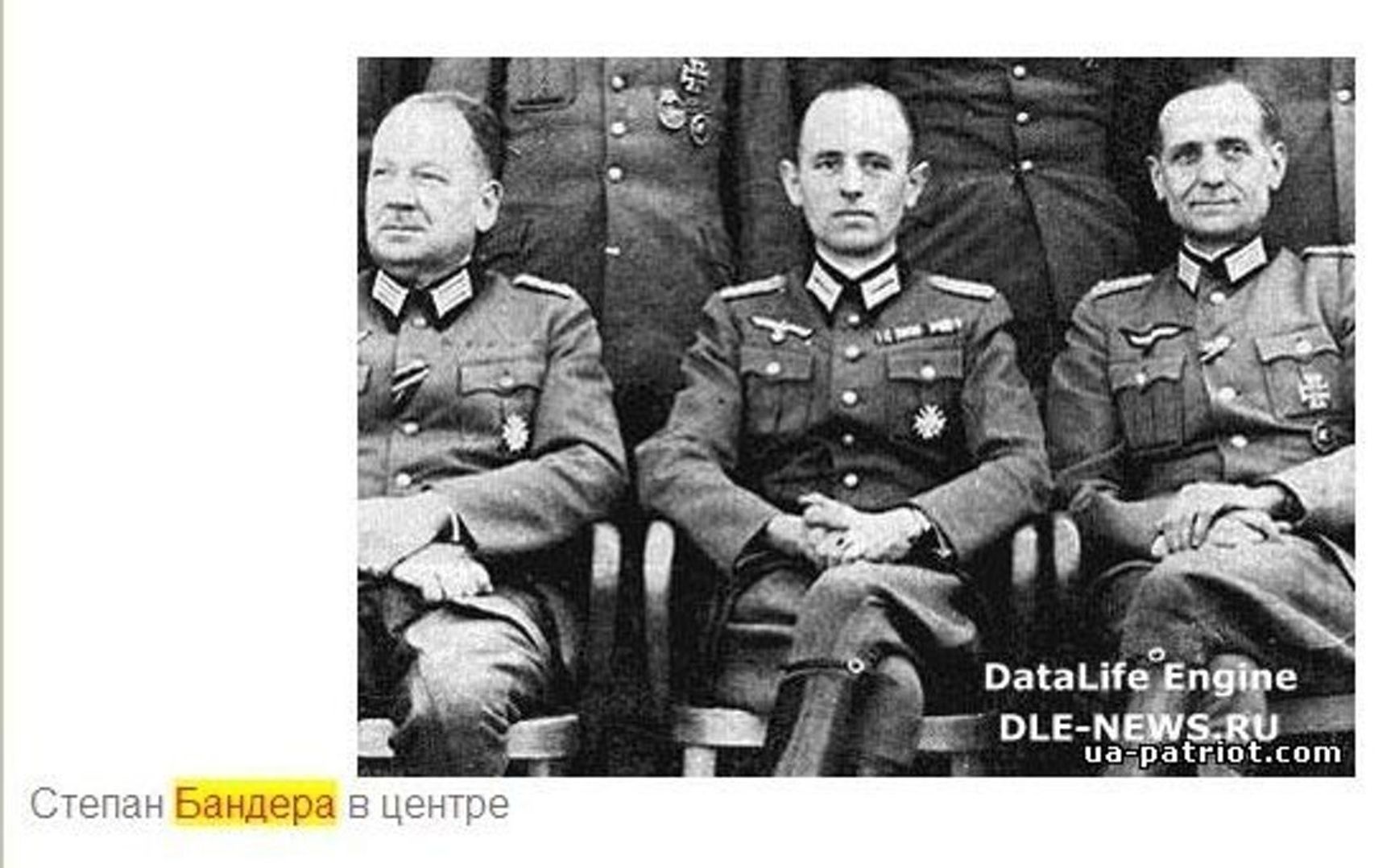

The Ukrainian Post is also Banderite

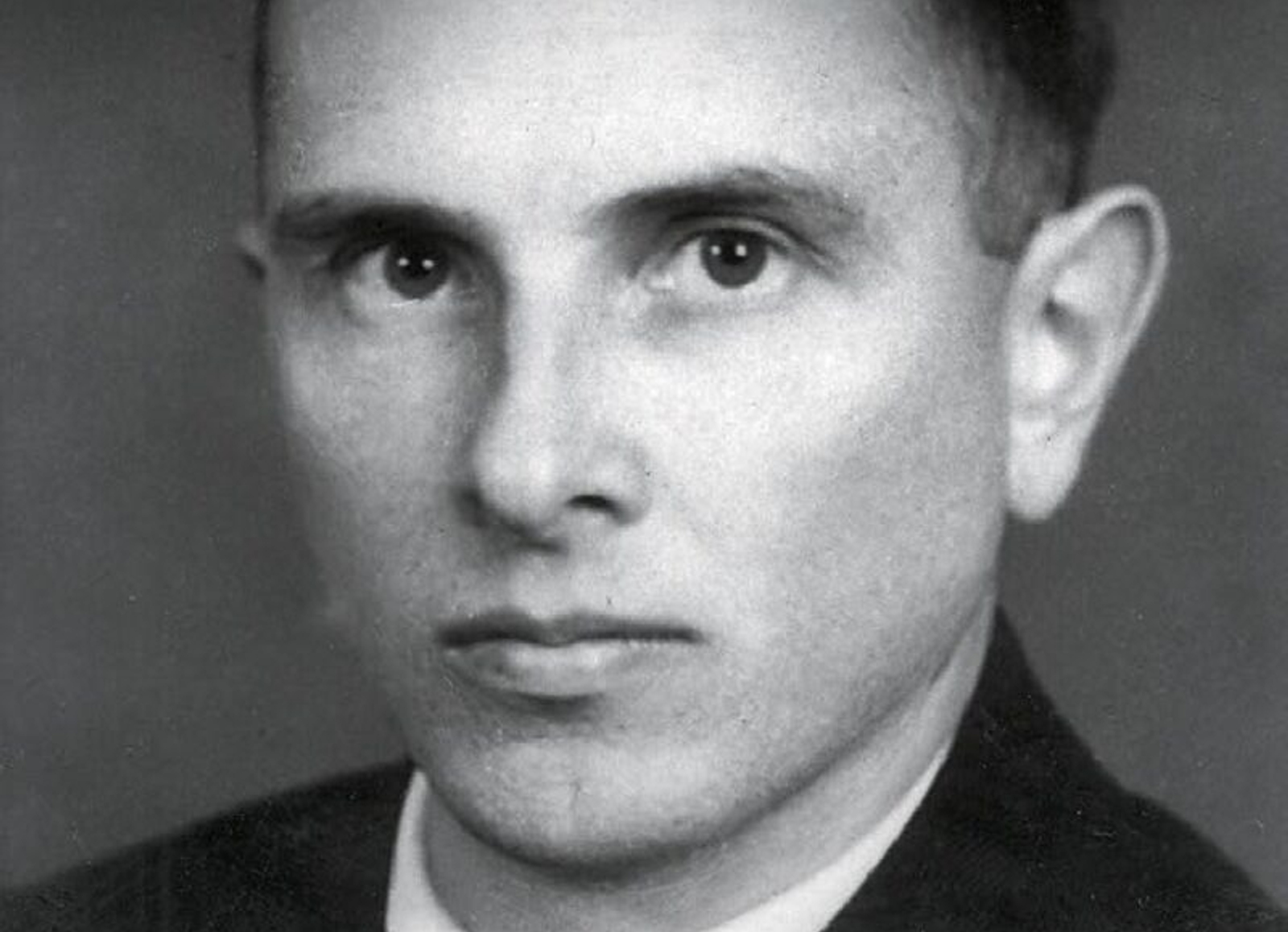

Stepan Bandera: the man behind the myth

Stepan Bandera was born in 1909 into the family of a Greek Catholic priest in the village of Staryi Uhryniv in the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, which then belonged to the patchwork Austro-Hungarian Empire under Habsburg rule. At the age of thirteen, he was detained for political activism but quickly released because of his unimportance. As a student, Bandera frequented multiple Ukrainian nationalist groups at the same time, finally joining the ranks of the OUN, where he streamlined the printing and delivery of underground periodicals.

Notably, the OUN emerged four years prior to Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in Germany, and therefore, contrary to the assertions of Soviet historians, does not owe him its existence. Was the OUN a terrorist organization? If it implies throwing bombs, following in the steps of Narodnaya Volya fighters in Imperial Russia, then yes, it was. The OUN targeted primarily adversarial political leaders with its acts of terror. Their most infamous attack was the assassination of Bronisław Pieracki, the Polish Minister of the Interior who had overseen the “pacification campaign” against Poland's Ukrainian population. According to Polish official sources alone, around 2,000 Ukrainians who disagreed with Warsaw's policies were arrested in Galicia over a few months in 1930. On June 15, 1934, Pieracki was shot by an OUN activist, and 26-year-old Stepan Bandera was charged and tried alongside a few others. The proceedings were in Polish, and Bandera, who kept shouting “Glory to Ukraine!”, ended up being removed from the courtroom. Found guilty of organizing the assassination, the defendants were condemned first to death, then to a life sentence. Bandera was released from jail in September 1939 thanks to the Third Reich and the USSR’s “special military operation” in Poland. It was then that Galicia fell under Soviet control.

Stalinist media painted the entrance of “Soviet liberators” into Western Ukraine as a “salvation of a brother-nation”, which, allegedly, welcomed the Red Army with flowers and feasts. In truth, the people of Galicia were less than thrilled with Red commissars replacing Polish landowners. No one was looking forward to collective farms or giving up their culture and the Uniate Church. Mass repressions soon followed, especially against the OUN. One of the demonstrative trials, known as the “Trial of Fifty-Nine”, ended with forty-two Ukrainian defendants, including a sixteen-year-old activist, condemned to execution by a firing squad. In the period from 1939 to 1941, the Bolsheviks deported hundreds of thousands of Western Ukrainians without charge or trial. The NKVD's atrocities provoked a backlash from the nationalist underground movement. In February 1940, Stepan Bandera announced the creation of the Revolutionary OUN in German-occupied Kraków. His faction of the movement called itself OUN Revolutionaries (OUN-r) or the Banderites (OUN-b). The other faction, led by Andriy Melnyk, was known as “the Melnykovites”, the OUN-m, or OUN Solidarists (OUN-s). Further on, the Banderites created the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) with the legendary Roman Shukhevych as its leader.

The Melnykovites are barely known in Russia, but it was their faction that collaborated with German occupants after 1941. Meanwhile, the Banderites decided to fight for Ukrainian independence against both sides. The OUN-m had a less radical agenda and sought primarily to make the occupation easier on Ukrainians. To that end, they conceded to forming local governments accountable, to one degree or another, to the German administration. However, the Nazis had to rebuff the Melnikovites as well, which often resulted in arrests and prosecution. For one, the Ukrainian National Rada (“Council”) convened in Kyiv by the OUN-m was seized by the Gestapo up to the last member. In response to the Act of Ukraine’s Independence Restoration announced by the Banderites on June 30, 1941, the Nazis made it crystal clear to the occupied Ukrainians that it was not the Ukrainian State they would be living in but occupation districts and Reichskomissariats. The hopes of certain OUN activists that Germany would be open to granting Ukraine a status similar to that of allied Croatia or Slovakia were dispelled. Stepan Bandera was sent to Sachsenhausen. Andriy Melnyk, who was more cautious and cooperative, ended up there later, in 1944.

Soviet historians wrote that Bandera’s imprisonment had been “pro forma” and that he had been kept in good conditions. However, the terms of his incarceration were standard for political figures of the time. Far from all Ukrainian nationalists made it out of German torture chambers alive. Thus, outstanding OUN-b activist Ivan Habrusevych and Oleh Olzhych (Kandyba) died during interrogation in the same Sachsenhausen camp.

Soviet historians wrote that Bandera’s imprisonment had been “pro forma” and that he had been kept in good conditions

Why did the Soviets brand Bandera and his followers, and not Melnyk's faction, as Hitler's staunchest supporters? In all appearances, they were consciously or unconsciously reproducing the logic of Nazi ideologists: since the Banderites were more unappeasable, fanatical, uncompromising, and hostile to any foreign power, be it German or Soviet, they were constantly labeled as everyone's archenemy. Coincidentally, while the Nazis accused the Banderites of ties to Moscow, Moscow regarded them as diehard Nazis after the war. The relatively moderate Melnykovites seemed insufficiently active and aggressive for that role. In turn, Putin’s ideologists and propagandists simply made use of Soviet playbooks they inherited.

The Banderites vs. the world

The Ukrainian nationalist underground was never homogeneous and could not be reduced to Bandera’s and Melnyk's movements. There still are many blind spots in the history of the 1943 Volhynia massacre, when Ukrainian insurgents slaughtered Polish civilians in revenge for the many years of Polish oppression of Ukrainians; revenge that was indiscriminate, brutal, and criminal – regardless of the reasons used to justify it. Bandera, a prisoner at Sachsenhausen at the time, was not complicit in this outrageous bloodshed. The specter of the Volhynia massacre is often raised by pro-Kremlin Russian historians who detest the rapprochement of the Ukrainians and the Poles. The historical wound is gradually healing, and as we may see, it is Poland that is the most active in providing aid to Ukraine in the ongoing catastrophe.

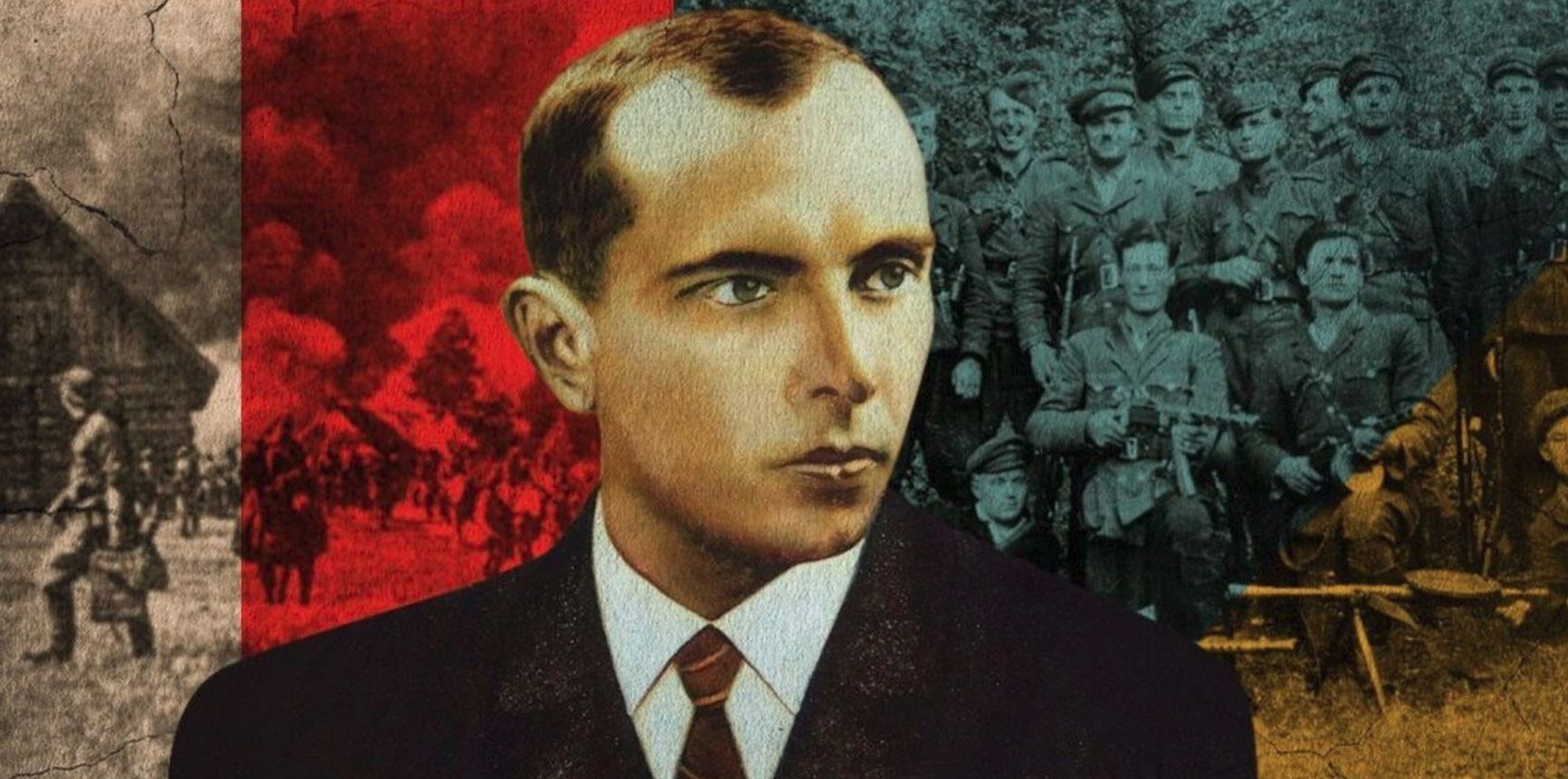

A modern collage with a portrait of Stepan Bandera

The facts are such: during the Second World War, Ukrainian nationalists fought their own battle against everyone else: Polish paramilitary units, the Red Army, pro-Soviet partisans, and Hitler's troops. All involved in this struggle are known to have committed unspeakable atrocities, and even within each group things often got out of hand.

There is abundant evidence of the Third Reich's mistrust or downward hostility towards the Banderites. In November 1941, an Einsatzgruppe (task force) of Sicherheitspolizei (Security Police) and SD reported that “Bandera’s movement is preparing an uprising in the Reichskomissariat” and that his fighters had to be captured and neutralized. Signed by an SS officer, the report was presented at the Nuremberg trials. Another noteworthy document was published in the Ukrainian emigrant press in 1970: an intercepted report by Soviet intelligence to Joseph Stalin dated December 5, 1942, on the activities of Ukrainian insurgents and the presumed execution of “prominent nationalist Bandera” by the Nazis. In 1941, the German Einsatzgruppe operating in Poland registered an increase in anti-German activities of the Banderites, who “spread nationalistic political ideas” and presented “an urgent threat to our present and future”. The SD and Gestapo wrote numerous reports on Banderite diversions and the confiscation of their newspapers and leaflets. In 1943, the Nazis printed a leaflet trying to convince Ukrainians that the OUN was acting in the interests of “bloodthirsty Stalin and his Jewish guard dogs”.

Admittedly, collaborationism was present in Ukraine – just as it was present in Russian and Belarusian territories. A great many people saw Germany as a force capable of delivering their peoples from Stalin's oppression: hence the volunteer Cossack (Russian), Baltic, and Middle Eastern Waffen-SS units, the massive Vlasov movement (Vlasov was a Soviet general who collaborated with the Nazis) and Ukrainian special battalions Roland and Nachtigall. Some of the collaborationists remained loyal to the Germans until the end, but many soon grew disillusioned or tried to pursue activities independently from their German superiors. Nachtigall and Roland officers were arrested in 1942 and remained incarcerated, while their battalions were disarmed. The personnel of the battalions refused to renew their contracts after the Nazis denied Ukraine its independence. As for the 14th SS-Volunteer Division «Galicia”, its personnel set themselves apart from the UPA and Bandera’s “forest gangs”. OUN-b members often branded SS volunteers “traitors”, infiltrated their ranks to win them over, and boycotted the division's mobilization campaigns.

Admittedly, collaborationism was present in Ukraine – just as it was present in Russian and Belarusian territories

«A stubborn Slav»

In 1944, Bandera was released from Sachsenhausen. Aware of their impending doom, Nazi commanders were prepared to use any anti-Soviet forces available to hold the Eastern Front. However, the collaboration never happened because the OUN leader once again demanded that Berlin recognize Ukraine's independence, which it refused to do. On October 5, 1944, Bandera met with Gottlob Berger, the chief of the SS Main Office. Here is how Berger characterized the leader of OUN-b in his report: “Bandera is a difficult, stubborn, and fanatical Slav. He is loyal to his idea to the end. Invaluable to us at this stage, he will later become a threat. He hates both the Russians and the Germans with a passion.”

After his release, Bandera stayed in Germany. The OUN-b was plagued by controversy, falling apart into more factions. Bandera’s staunch supporters who had survived Nazi imprisonment (and called themselves katsetniks, from KZ – the German abbreviation for “concentration camp”) demanded that Bandera should become the leader of both the OUN’s foreign groups and the OUN in Ukraine and that the movement should return to its 1941 program and continue its armed struggle against the Soviet Union. OUN members operating within Ukraine, or the kraeviks (from krai, a Ukrainian administrative unit), were opposed to those initiatives, dismissing them as unrealistic.

In all, the Banderites continued their struggle: those in emigration leveraged Western media, diasporas, and their cooperation with U.S. government agencies and NATO structures, while those who remained in the USSR fought with weapons in the cities, villages, and forests of their motherland. Soviet secret services gunned down Roman Shukhevych outside Lviv only in 1950, but even then his fighters did not surrender. In the period from 1944 to 1956, the USSR continued its crackdown on the armed Ukrainian underground, also punishing the many civilians who were aiding and abetting the insurgents. As a result, they arrested over 103,000 “Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists and fascists”, of which around 90,000 were convicted. Another 203,000 Ukrainians were deported beyond the Ural mountains or to the Soviet republics in Central Asia.

Stepan Bandera was assassinated in Munich on October 15, 1959, by KGB agent Bohdan Stashynsky, who had been following his target from January of the same year. As a weapon, Stashynsky used a spray gun that fired a jet of poison gas. For want of high-tech nerve agents like Novichok, the device employed good old cyanide.

Shortly before his death, Stepan Bandera gave a speech in 1958 on the grave of Yevhen Konovalets, a founding father of the Ukrainian nationalist movement. He called the Third Reich and the USSR “two predatory totalitarian empires” which the OUN spared no effort in fighting while earning respect for “Ukraine's rights to sovereignty by other nations and countries – a respect that was the only possible platform for peace and international cooperation.