For the first time, European sanctions have struck at Russia’s gas sector — “the heart of its war economy,” as European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen put it. Imports of Russian liquefied natural gas will be partially banned in 2026 and completely prohibited by 2027. The EU also intends to phase out all other forms of Russian gas. Putin long wielded his “gas stick,” warning that without Russian energy Europe would freeze and Ukraine would go bankrupt. But European economies have adapted to the new conditions: the EU is no longer facing an energy crisis, and Russia has overestimated its own indispensability. As economist Vladimir Milov explains, the global market will be flooded with LNG in the coming years, and the EU will have a relatively easy time replacing Russian gas with American supplies.

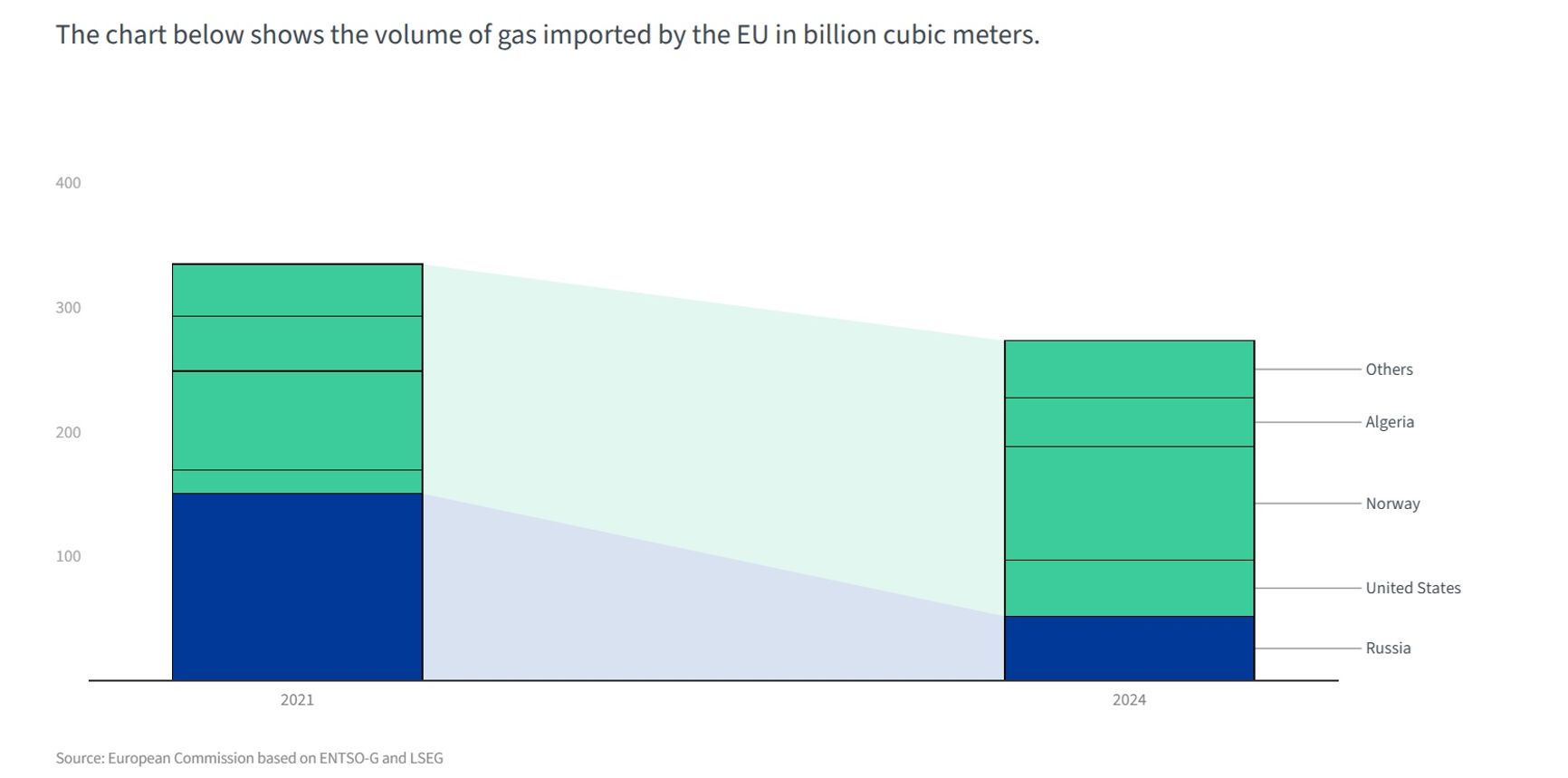

The EU has adopted a milestone plan for the gradual phaseout of Russian liquefied natural gas (LNG) and a complete halt to the import of all Russian energy resources by 2028. Since 1970, when the USSR and West Germany signed the “gas-for-pipes” deal, trade had served as a key element of the political rapprochement between Russia and Western Europe. For decades afterwards, Russia was the largest supplier of energy to European countries. Now, however, Russia’s aggression against Ukraine has led to a rapid reversal — one in which Europe is once again gaining full energy independence from Moscow.

Gas independence day

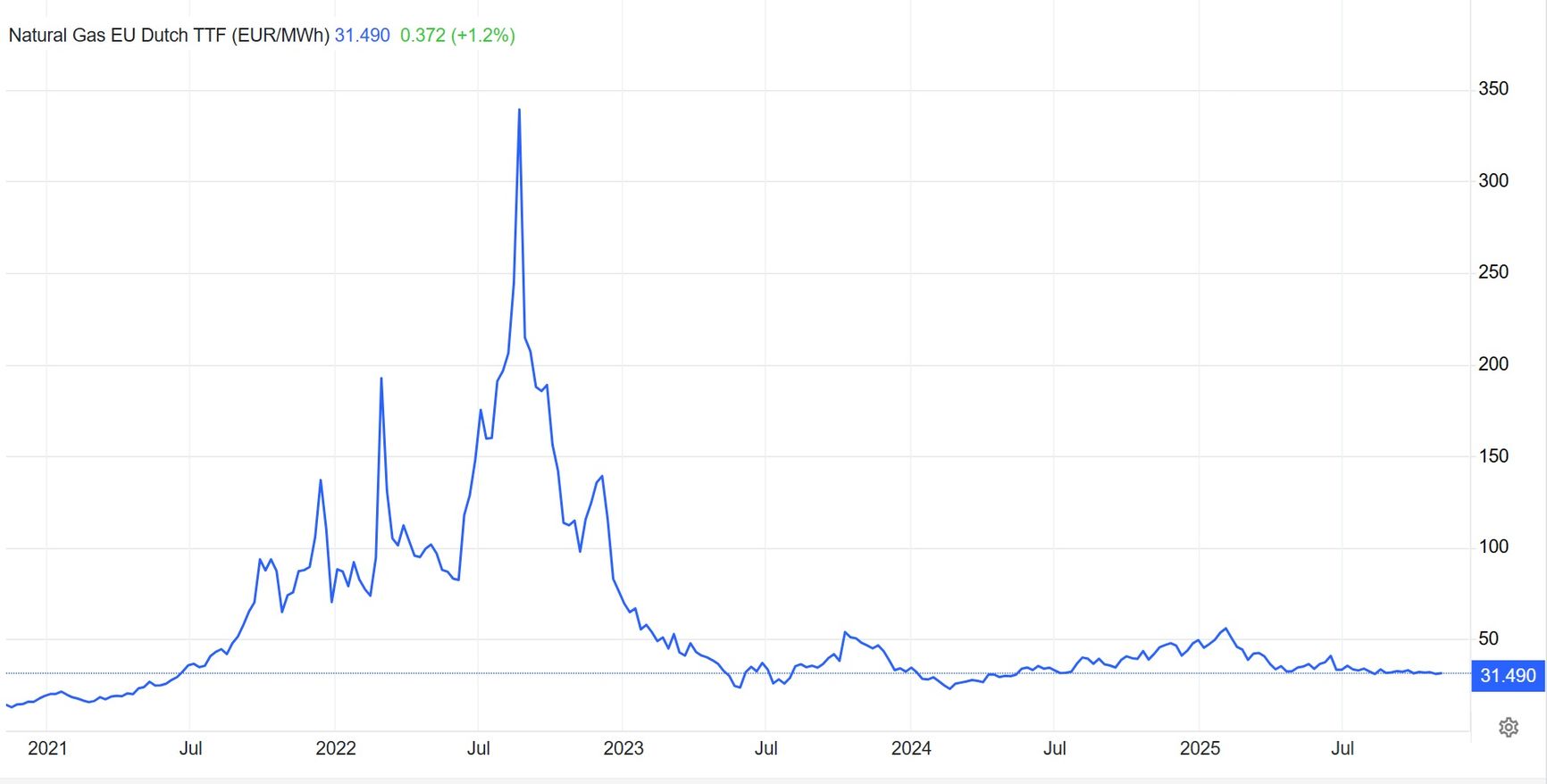

Even before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Kremlin propaganda insisted that Europe would “freeze” without Russian energy. Instead, the European market has found alternatives, and the price of natural gas at the key European TTF hub in the Netherlands has remained stable over the past three years, ranging between 30 and 50 euros per megawatt-hour.

This level is somewhat higher than before 2022, when prices in the range of 10–20 euros per megawatt-hour were considered normal, but it is still far from catastrophic for European economies. The main suppliers of natural gas — in addition to Norway, a non-EU regional actor — are now the United States, Algeria, Qatar, and Azerbaijan.

Source: Tradingeconomics

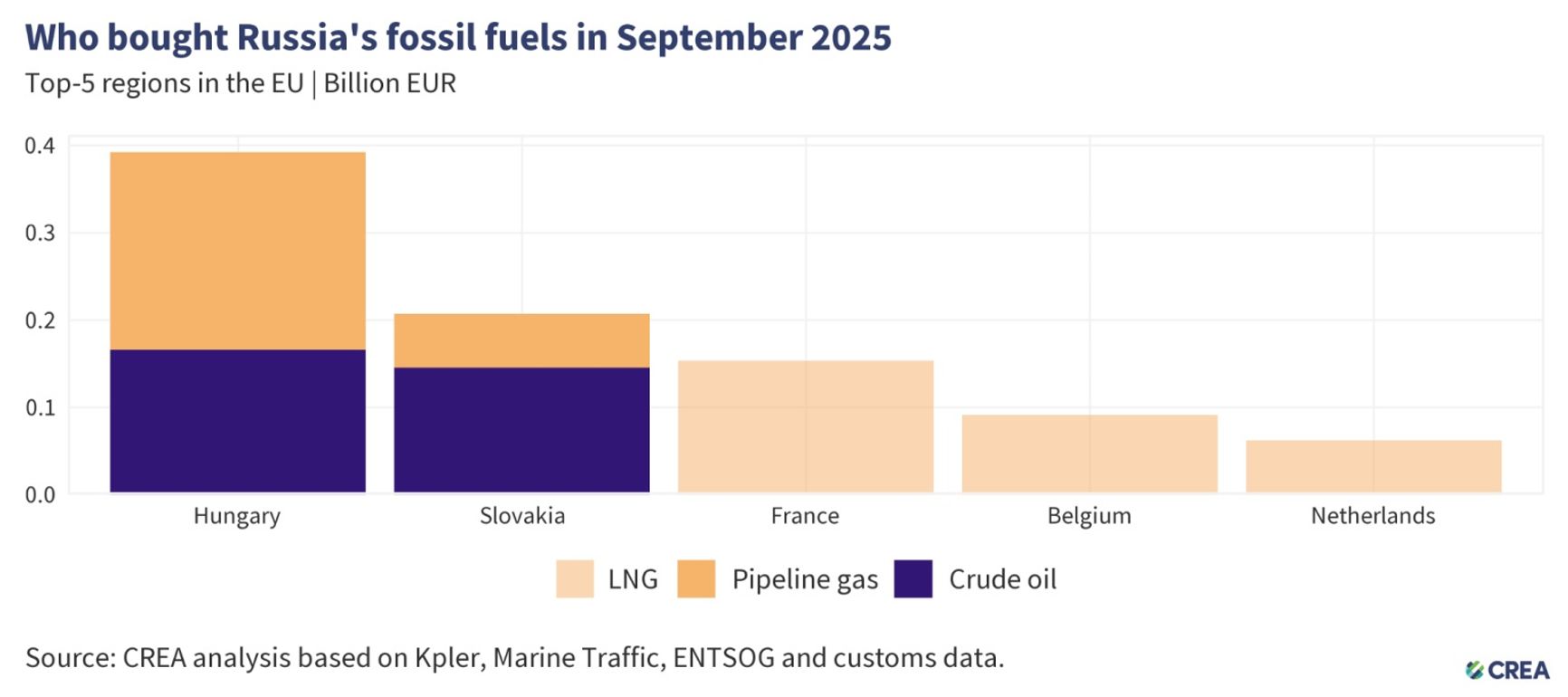

Additional sources of oil and gas have proven more than sufficient for Europe, and the continent’s remaining purchases of Russian energy are largely explained by the Kremlin-friendly stance of the Hungarian and Slovakian governments. According to calculations by Lithuania’s Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, these two countries account for two-thirds — roughly 600 million out of 900 million euros per month — of the EU’s oil and gas imports from Russia, with the remaining third being purchased by a collection of Western European nations. By historical standards, the EU has actually overcome its dependence on Russian energy remarkably quickly.

Finally, the bloc has found a way to rein in even Hungary and Slovakia: the amendments to phase out Russian oil and gas will be adopted through changes to EU trade law, which individual member states cannot veto. Both countries have already announced that they will fight these changes, but they likely lack the political clout to do so successfully. Hungarian elections scheduled for April 2026 could bring a change in the country’s political course, and Slovakia will also go to the polls before 2028 — meaning these countries may actually stop resisting the EU’s policy of their own accord.

The EU has overcome its dependence on Russian energy remarkably quickly

In 2024, the value of the EU’s imports of Russian oil and gas amounted to just 21 billion euros — more than 80 percent below the 2021 level. For those who might say that 21 billion euros is still a large sum, it bears repeating that its largest share of purchases comes from just two relatively small countries pursuing an anti-Brussels course. Therefore, criticism of the EU for “continuing to fund Russia through oil and gas imports” is not entirely justified and would more accurately be directed at Budapest and Bratislava. In any case, this year the EU’s oil and gas imports from Russia are expected to fall below 20 billion euros, and they should drop to zero by 2028.

In addition to the EU, Russia now has another major headache — Turkey. Today, amid the sharp decline in gas exports to Europe, Turkey has become the second-largest buyer of Russian gas after China. However, unlike China, which receives gas at a price that is barely profitable for the seller, Turkey accounts for the lion’s share of Gazprom’s profits from its European operations. But that will not last long.

First, Turkey is leading the way in developing renewable energy from solar and wind sources, which have already offset about $15 billion in gas import costs from July 2022 to December 2024, according to Ember. Electricity generation from solar and wind in Turkey now exceeds that from natural gas, and the gap will only continue to grow. Second, Turkey has discovered large gas fields on the Black Sea shelf and plans to ramp up domestic production, along with increasing LNG purchases from the U.S. to curry favor with Donald Trump. Against this backdrop, Russia’s gas exports to Turkey are facing headwinds.

The pivot to Asia did not help

Overall, Europe's energy divorce from Russia has been a sad affair. In economic terms, Russia had a tremendous natural competitive advantage: the ability to supply raw materials from Western Siberia and other regions over relatively short transport routes. Instead of waging wars, playing geopolitical games, and forcibly redrawing borders on the European continent, as Putin chose to do, he should have built a shared, peaceful, market-oriented, democratic space — one in which Europe would have had a stable and reliable energy supplier, and Russia a steady source of income.

If not for Putin’s geopolitical games, Europe would have had a stable and reliable energy supplier, and Russia a steady source of income

Today, it has become clear just how costly and economically pointless Russia’s pivot to Asia has turned out to be. A turn toward markets that are much farther from its main oil and gas production sites has entailed prohibitively expensive infrastructure and transportation costs. Moreover, Asian buyers have gained leverage over Russia and can demand discounts thanks to the fact that Putin’s reckless adventures have left Russia with no alternative buyers in the European market.

It is Russia, not Europe, that has lost the most from the energy divorce. In 2021, Gazprom exported 185 billion cubic meters of gas to Europe (including Turkey); by 2024, that figure had dropped to just 28 billion. Over that period, the company lost roughly 100 billion cubic meters — about one-fifth of its annual production.

True, gas exports to China have increased, but they are far less profitable. In 2023, Gazprom reported an annual loss, and in 2024–2025 its profits were largely sustained by other business segments, such as oil operations and the consolidation of Shell’s stake in the Sakhalin-2 project. At the St. Petersburg Economic Forum this past June, Russian Minister for the Development of the Far East and the Arctic Aleksei Chekunkov complained that Gazprom’s vast production and transport capacities in Western Siberia and northwestern Russia are standing idle due to the loss of the European market.

A lose-lose game

Europe, of course, has had to bear its own costs. Direct government support for businesses and households during the peak of gas prices in 2021–2022 alone cost national budgets around 700 billion euros.

Even at the start of the 2021–2022 cold season, several months before the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Gazprom began halting gas supplies to Europe under various pretexts, causing prices to skyrocket to several thousand dollars per 1,000 cubic meters of gas. In retrospect, it has become clear that this was part of Putin’s deliberate strategy in the run-up to war. The Kremlin sought to severely complicate Europe’s energy situation during the winter and exploit its dependence on Russian gas to soften the EU’s support for Ukraine and resistance to Putin’s aggression.

Putin’s plan failed: the EU quickly saw through Gazprom’s manipulations and spared no expense in taking immediate measures to reduce its dependence on Russian imports. At the time, this was a crucial element in enabling Europe's support for Ukraine and unity in the face of Putin’s aggression. By the time the full-scale invasion began, Europe was already seeking alternatives to Gazprom’s gas, and the Kremlin’s attempt to bring Brussels to its knees through energy blackmail fell flat.

The price the EU had to pay, as already noted, was high. Gas prices at the TTF hub are now about 1.5 times higher than before Gazprom’s sabotage began. Even after prices stabilized in 2023, Europe has still been incurring additional costs of 20 billion euros a year. The eurozone’s economic growth is hovering around zero — in part a result of higher energy prices. But at the same time, the EU’s nominal GDP reached nearly 18 trillion euros in 2024, meaning that the added cost of pricier gas amounts to a tiny fraction of even one percent of the EU’s total GDP.

In short, any outcry over the “tragic consequences of giving up cheap Russian gas” is a narrative pushed only by Russian propaganda. The EU is deliberately spending money to confront a far greater threat: aggressive Russian imperialism. In the end, no one has had it easy, but Russia’s losses are far greater — and Europe shows no sign of “freezing.”

No one has had it easy, but Russia’s losses are far greater — and Europe is in no danger of “freezing”

What impact will the EU’s new plan for a complete phaseout of Russian energy resources have? It will hit Russia’s natural gas exports first and foremost. Today, natural gas accounts for three-quarters of all revenues from Russian oil and gas exports to the EU — more than 700 million euros per month. Gazprom will lose what remains of its profitable supplies, making it increasingly difficult to offset its losses. The company has so far failed to make gas exports to China profitable and acknowledges that prices on that route will be significantly lower — a fact effectively confirmed by the government’s recent budget projections. The loss of a significant share of the Turkish gas market will exacerbate the situation.

The company that will suffer the most from the new sanctions is not Gazprom, which has already lost almost everything in Europe, but Novatek, Russia’s second-largest gas producer. More than two-thirds of exports from Novatek’s Yamal LNG project currently flow to Europe, and the company will lose that entire market. Redirecting such volumes (20 billion cubic meters of gas per year) to Asia will not only necessitate larger discounts and sacrificed revenue, but will also pose serious technological challenges.

Novatek lacks Arc7 ice-class LNG carriers, which were supposed to be built either in South Korea or with South Korean participation at the Zvezda shipyard in the Russian Far East. However, South Korean companies withdrew from projects with Russian clients after Russia’s aggression against Ukraine began, and China has been unable to step in as a replacement, lacking the necessary expertise in this particular field.

It is impossible to transport LNG to China via the eastern route without sufficient icebreaker support, and transshipment of LNG in European ports was banned by the EU this past spring, meaning there are no easy answers for Novatek. As a result, the company is set to lose a significant share of its profits.

Who will replace Russia in the European gas market?

The question of where Europe will meet its energy needs is nowhere near as pressing as it seemed three years ago. Today, the world is looking at a global surplus of LNG in the coming years — especially after 2030. By then, new LNG export capacities in the U.S. and Qatar will go online, while global demand for energy is projected to slow along with the broader world economy.

There has been much talk about Trump’s lobbying efforts to replace Russian gas on the European market with American LNG, but this is hardly a new development: the increase in these supplies has been the result of joint efforts by the European Commission and the Biden administration starting from 2022. Rather, Trump is acting as a traveling salesman, promoting all kinds of American products — from chicken and soybeans to liquefied natural gas.

What will happen to Hungary and Slovakia after the complete phaseout of Russian oil and gas?

Nothing dramatic. Remember the uproar Viktor Orbán and Robert Fico caused when the transit of Russian gas through Ukraine stopped? They shouted that their citizens would freeze and that responsibility for the terrible consequences would be on the conscience of Kyiv and Brussels. In the end, however, gas flows from Russia ended up being redirected through the underused TurkStream pipeline. No one suffered, and gas prices in Europe quickly stabilized after the January panic.

A global LNG surplus is projected, especially after 2030, when new capacities in the U.S. and Qatar go online and global demand growth slows

The same will happen this time. There is plenty of gas and oil on the market, and Hungary and Slovakia will easily find alternatives. All claims about threats to their energy security are nothing more than political noise.

Here a few words should be said about the final nail in the coffin of the Nord Stream pipeline, which the EU drove in by adopting its 18th sanctions package this past summer. The pipeline is now permanently banned in Europe, and gas deliveries through it will not be revived. Not even the mysterious involvement of “American investors,” who were reportedly ready to mediate the resumption of Russian gas supplies to Europe via Nord Stream, will change this entrenched reality. Whether those plans were real or not no longer matters. The EU’s roadmap for phasing out Russian gas requires full traceability of the fuel’s origin — meaning it makes no difference who the intermediary is. If the gas came out of the ground in Russia, it falls under a total embargo.

EU Energy Commissioner Dan Jørgensen made it clear that the EU has no plans to resume purchases of Russian gas, even if the war in Ukraine comes to an end. Once again, Russia is learning that imperial ambitions come at a price — an exorbitant one.