The infamous anti-Semitic “pogrom” in Makhachkala, which failed to expose even a single Jew, sparked a debate on anti-Semitism in the North Caucasus. Diametrically different opinions have been expressed, from “there never were any anti-Semits here” to “anti-Semitism runs in the Dagestani and Circassian blood.” Journalist and North Caucasus expert Vadim Dubnov believes the unrest in Dagestan had nothing to do with Jews, Palestinians, or even fellow Muslims; its real cause was pent-up popular discontent that’s all too easy to direct toward any target.

A prologue: Cherkessk

“Not a single Circassian attended the anti-Israel rally in Cherkessk,” Circassian activists insist, reminding that they traditionally stay away from Karachay-organized protests in the capital of Russia's Karachay-Cherkess Republic. And this is just one of the countless nuances one has to consider when figuring out what happened in Russia’s North Caucasus late in October. The Circassian issue leaves its mark on Circassian and Kabardian civil protests, not to mention the existence of a small but noticeable Circassian diaspora in Israel and the historically complicated relations between the Circassians and the Palestinians. Therefore, as Nalchik insists, there is no public demand for particular solidarity with Palestine in Kabardino-Balkaria.

On the other hand, the Karachays themselves are divided on the rally in Cherkessk. Representatives of social movements who could treat the event as an achievement are denying their involvement. Someone reluctantly mentions a mysterious Skoda with Moscow license plates and a Palestinian flag, which allegedly drove around the square in Cherkessk before and during the rally. Others make vague references to their wives or girlfriends, talking about women's online communities that hosted intense discussions of some sort – and that could be true too.

There’s no evidence against the protest having been funded with Middle Eastern or Turkish grants, and the current migration trends speak in favor of this version. However, the very slogans about Israelis who allegedly chose to seek refuge in Cherkessk, of all places, hint at those who don’t differentiate between organizing a United Russia gig and a rally of solidarity with the Palestinian people. What matters in this case is how many people joined the protest: just a few hundred, with curious bystanders making up at least half of the crowd.

But then Dagestan happened.

Theory and practice of combustion

For all their tragicomic nature, the events in Dagestan cannot be considered in isolation from Cherkessk. Why did things blow up in Dagestan but not in Cherkessk?

Cherkessk is a predominantly Russian city. The Karachays and the Circassians are national minorities, barely making up half of the population put together, and their relations are historically rife with contradictions. What's the point of staging a nationalist action in an environment with no chance of unanimous support? As for slogans about deportation, the generational memory of Soviet-time deportation runs too deep among the Karachays themselves.

The generational memory of Soviet-time deportation runs too deep among the Karachays

Therefore, the version about a local official having a sudden urge to show solidarity with the Palestinians looks quite accurate from the formalistic standpoint. Presumably, even the local Federal Security Service realized the protest would be pro forma only. They would’ve been right if Dagestan hadn't picked up the torch.

In all appearances, this was exactly the case. The similarity of slogans in just a day's time suggests imitation rather than coordination. And whereas such a call to the masses could have become a material force in many places throughout Dagestan, Khasavyurt becoming the epicenter of the unrest was a logical and even partly symbolic outcome.

There was also a certain logic to looking for Jews in the hotel: with hardly a dozen Jewish families left in the city with a population of 140,000 people, looking for them in the streets was pointless. But the old Marxist saying that “the goal, no matter what it is, is nothing; the movement is everything” aptly sums up what transpired in Dagestan.

Twenty years ago, Khasavyurt’s crime rate soared; for a decade or so, it ranked first in the republic by the number of special operations against Salafists. Times have changed, of course. But even if the number of young justice warriors has somewhat dwindled, recruiting a few hundred fighters is still not a challenge. However, what may look like successful “mobilization to destroy” is in fact more of an explanation of how and why the chain reaction got out of hand.

Whereas Cherkessk illustrates the futility of orchestrating protests, Dagestan is a textbook example of how you can inflame the masses. For a more accurate assessment, we need to separate what is emotionally so easy to combine and draw the line between anti-Semitism and support for Palestine.

Dagestan is a textbook example of how you can inflame the masses

The empire's last Jews

As many scholars have correctly pointed out, where there are Jews, there is bound to be anti-Semitism. Ethnographer Valery Dymshits offers a salient point, arguing that anti-Semitism is not an ideology but a “dormant element of consciousness.” Alternatively, the two concepts could characterize two different kinds of anti-Semitism.

The first is systemic. It does require Jews, and it was what we observed in Europe – primarily in Germany and Poland. In The Meaning of Hitler, Sebastian Haffner reiterates that the story of Jews in Germany resembled a happy marriage, thus confirming the thesis of anti-Semitism being an element of consciousness. In Germany, it emerged easily, but in Poland and further east, the story developed along the lines of the rational and thoroughly explored model of competition between natives and outsiders. This kind of anti-Semitism was also exacerbated by a power imbalance and an explicit administrative preference given to the locals, whoever they were – Poles, Ukrainians, or Lithuanians. Fueled by both practical considerations and all sorts of myths and libel, this element of consciousness was never really dormant in the first place. Importantly, as effective as it was, anti-Semitism was always undeniably secondary.

The Caucasian case is much more complicated. On the one hand, the Jews became part of its ethnic and cultural landscape before or during the formation of more or less stable ethnicity-based entities. So even if the outsider motive played its part early on, further tumultuous events largely nullified it. In part, this delivered the Mountain Jews of many of the restrictions imposed on the empire's Jewish population elsewhere in Russia, such as the Pale of Settlement, although even they faced obstacles when traveling in some areas.

And this memory lingers, both among the Jews and in the perception of their neighbors. Jews remain part of the local tradition: Nathan, who lives next door, is first and foremost your neighbor and only then a Jew. Even the religious canon retains signs of compromise, and a European Jew’s confusion at the sight of a large ablution washroom in the Derbent mosque perplexes locals. Ever since the Soviet Union collapsed, separating Russia from former Soviet republics with a long Jewish tradition, shtetls, compact settlement areas, and the legacy of a once-influential community, the Mountain Jews’ position in Dagestan is unique in Russia.

Nathan, who lives next door, is first and foremost your neighbor and only then a Jew

Anti-Semitism without Jews

On the other hand, this seemingly benign story is fraught with episodes that seem borrowed from the tragedy of Eastern European Jews. The Civil War was accompanied by pogroms, and while some attribute them to Jewish support for the Bolsheviks, the similarities with Ukraine and Lithuania are haunting.

Anti-Semitism in the North Caucasus extends beyond the combination of its aspects – systemic, rational, prejudicial... It relives them, stage by stage. Unsurprisingly, there were no pogroms in Soviet times. The Jews followed national patterns, first engaging in the nationwide struggle against the Israeli military, then starting to trickle to Israel in the 1970s, when Soviet aliyah began. However, things changed in the 1990s.

“We're leaving!” my cheerful interviewees in Derbent told me five minutes or so into our conversation, as if to propose a toast for both the promised land, which they only knew from the letters of last year's emigrants, and the land they were leaving – even though no harm had come to them here. “Russians may have it even harder here now,” they admitted.

Who would dare dissect the anti-Semitism of the 1990s? Artur Petrovsky, Vice President of the Soviet Academy of Pedagogic Sciences, recalled how Professor Viktor Kan-Kalik became rector of the Chechen-Ingush University: “In all probability, [his appointment] was related to interethnic relations in the republic. It was assumed that the Chechens did not want to see an Ingush in the rector's chair, and vice versa. A Mountain Jew was a safer option...”

A year later, Kan-Kalik was abducted and murdered, and it took law enforcers another year to locate his body. In 1991, [Chechen President Dzhokhar] Dudayev offered a ransom of 5 million but received no response....

To say there was no popular anti-Semitism would be an exaggeration. Among friends, some of whom were journalists, the aforementioned Dudayev made trivial jokes about Jews, to the approving laughter of everyone present, and would’ve been sincerely surprised to learn that some might take offense.

Even local Jews remained irrationally alien and alarming, and favoritism toward them required a particular open-mindedness – but it was hardly the reason to leave. To be more accurate, in the 1990s Chechnya, Jews suffered from their ethnicity indirectly, belonging to a large group of those who had no one to stand up for them, such as neighbors or a powerful clan. Furthermore, the Jews of Grozny, like most non-Chechens, had no villages where they could hide from Russian artillery and air raids during the Chechen Wars.

In the Caucasus, favoritism toward Jews required a particular open-mindedness

In Grozny, Jews settled in Baronovka, a prosperous neighborhood near the center. The area was bombed out during the First Chechen War, and in 1995 the Jewish Agency for Israel organized the evacuation of Chechen Jews from Mineralnye Vody. After the Second Chechen War, the district became known for its kebab makers, and today it’s dominated by Kadyrov's spectacular mosques. As it turns out, Jewish history can end very quickly even where their roots look strong.

The recently rebuilt Kele-Numaz Synagogue in Derbent boggles the mind with its splendor; yet it can easily accommodate all of Derbent's remaining Jews – four thousand or so, according to the most optimistic estimates. At this point, it's hard to say whether the exodus was caused by anti-Semitism or the opportunity that presented itself. In the absence of Jews, local anti-Semitism turns into its usual Russian variety – a set of myths and stereotypes, a vestige of consciousness devoid of any substantive foundation. What was always secondary becomes the only option, but the collective consciousness still holds recollections of a different time.

From the village of Karamakhi to the Flamingo Hotel

Anti-Semitism and solidarity with Gaza could be treated as communicating vessels, to some extent, but in a far more bizarre way than the laws of physics suggest. In this sense, ingenuous women from Cherkessk are not too different from their broad-shouldered kindred spirits in Khasavyurt or Makhachkala.

Caucasian anti-Semitism is gradually approaching the pointless perfection of its post-Soviet Russian counterpart: the Jews are an abstraction, as they should be for a real anti-Semite. You can't dislike all Jews in the same way you hate your neighbor Nathan – especially since you can’t really hate him for being Jewish. You have to detest them collectively, as an idea. Somewhere in Perm, Syzran, or Golyanovo, such anti-Semitism is enough to determine one's sympathies in the Middle East conflict. But things are a little different in the Caucasus.

Naturally, solidarity with Gaza is part of the cultural code, the regional DNA. As historian Mairbek Vachagayev believes, while Hamas's brutality played its part early on, it’s now fading into the background. Even fairly democratic publications (surprisingly, Dagestan still has a few) a priori align themselves with traditional preferences. And when the muftiate refused to recognize the war in Gaza as jihad (being obviously reluctant to address the matter of its own involvement), the Mufti's wife and advisor Aina Gamzatova was booed.

But it would be wrong to link this reaction to anti-Semitism.

On the one hand, Dagestan is the gate through which Islam traditionally entered the North Caucasus. Even what later became known as Wahhabism first entered Dagestan in the form of a rather moderate, “Protestant” version of Islam. In the famous village of Karamakhi, which engaged in a lucrative apple trade with central Russia in the mid-90s, the first Wahhabis were peacefully fixing their KAMAZ trucks while explaining to me, like medieval followers of Martin Luther, how important it is to adhere to the Scriptures, which condemn lavish weddings and luxury in general. A few years later, however, the people of Karamakhi looked completely different: unsmiling, camouflage-clad men with assault rifles, who searched our car thoroughly and stared hard into the eyes of the Avar driver to see if he’d been abusing any substances.

Not long ago, a similar change occurred to the phenomenon called “The Forest” – the underground movement of Salafi rebels dreaming of an Islamic state. Of course, some were true religious romantics. Others had all sorts of reasons for detesting the state in its available form. Some had lost the republican struggle for power; others still were secular oppositionists – or someone's blood enemies who needed somewhere to hide. A tangle of religious ideas, political conflicts, national rivalries, and banal criminality was forming in Dagestan as far back as the 1990s (or even earlier, in Soviet times).

Today, it’s taken on a distinctly Islamic character, which suits everyone – and which wasn't a major transformation anyway. There was no need to Islamize Dagestan as the Islamic tradition was always strong here. However, the recent closing of “The Forest” triggered two simultaneous processes. On the one hand, Islam in Dagestan gradually returned to its traditional, relatively moderate form. On the other hand, the tumultuous events inevitably caused the emergence of a huge mass of young neophytes who know more about Islam from television, so to speak, than from teachers or elders. And on TV, the global Ummah is fighting for a free Gaza.

In Dagestan, young people learn about Islam “from television,” where the global Ummah is fighting for a free Gaza

Indeed, Dagestan supports Gaza by default, like almost the entire North Caucasus – because this stems from the mindset, from the notions of good and evil. For most people, these general categories aren't reason enough to gather in the city square, let alone on the airfield of Makhachkala airport. However, Dagestan is both politically and historically almost the only Russian region that hasn’t lost the taste for mass protests any government has to reckon with.

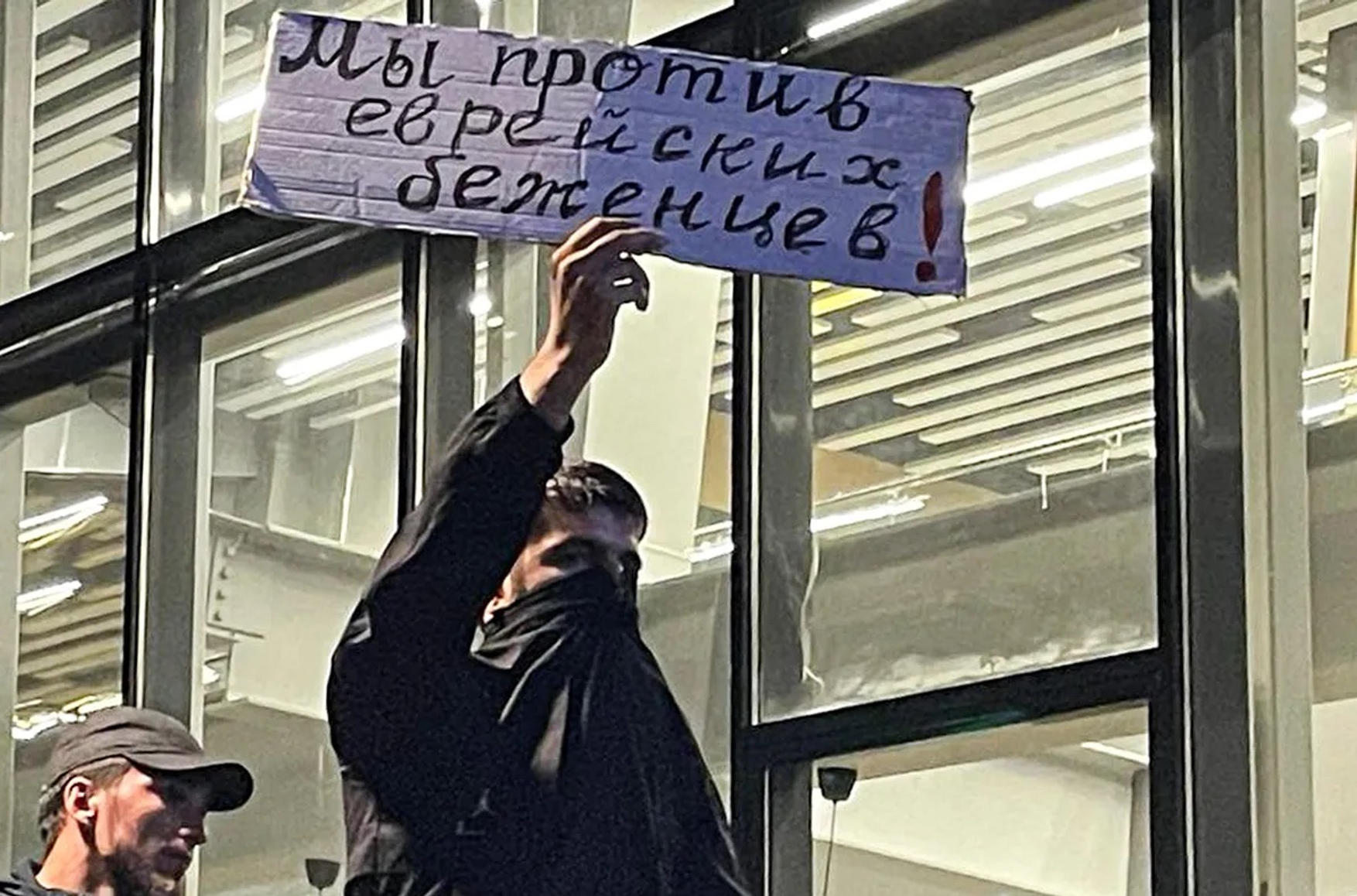

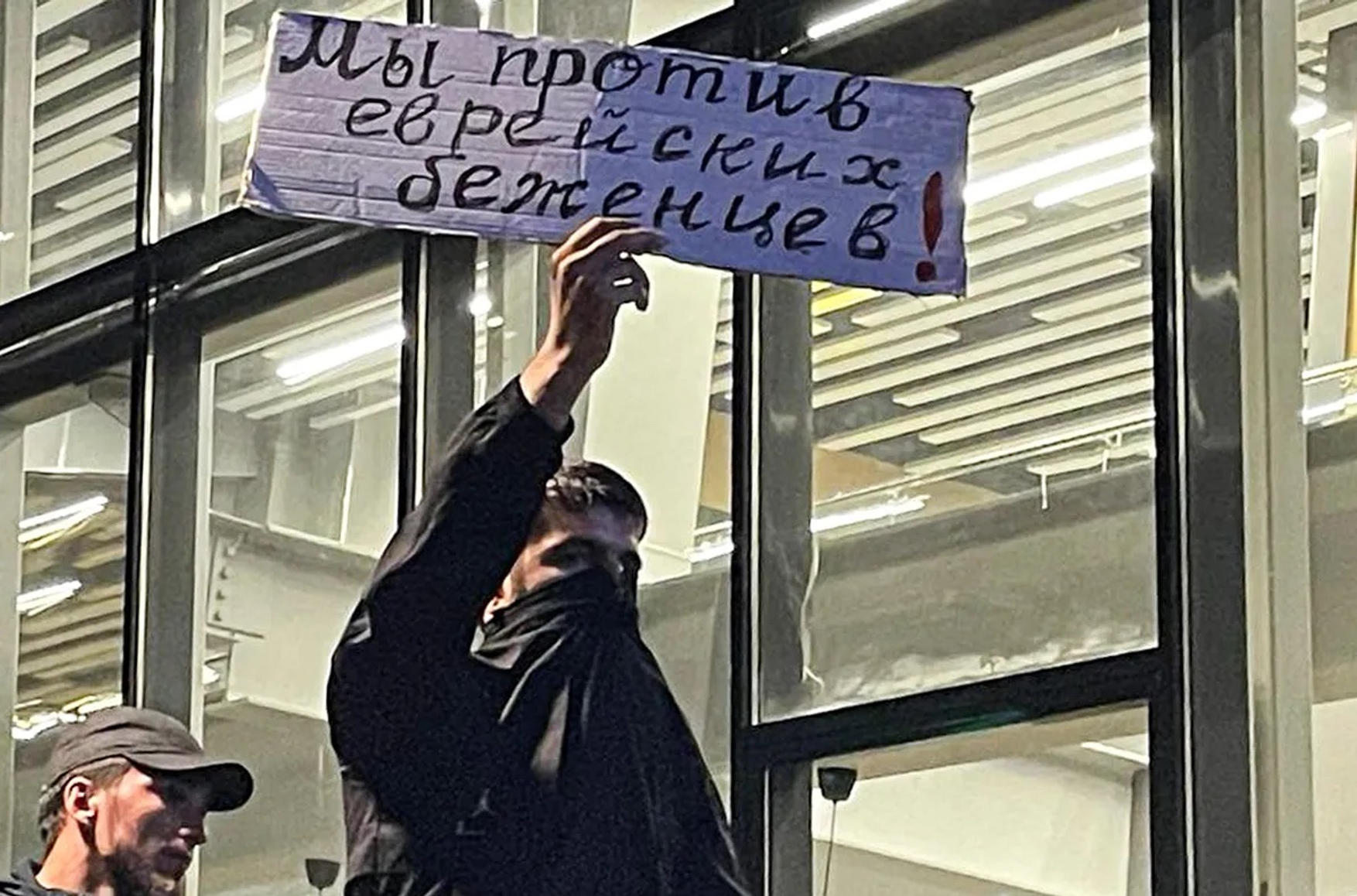

Few are willing to bridge the gap between solidarity with their Palestinian brothers and hatred of all Jews (and not just the state of Israel). But those who take this leap are the ones who go down in history. In the world of those who came knocking on the doors of the Flamingo Hotel, there are no Jews, Palestinians, ideological Muslim brothers, European leftists, or even Greta Thunberg. Their anti-Semitism is the proverbial “element of consciousness” that rose to the occasion, as random and senseless as the capture of the airport, as imitative as Cherkessk women striving for solidarity with Palestine, and as prejudiced as Russian anti-Semitism in general, forever struggling with a pronounced shortage of Jews.

Although they are a minority, their presence is still sufficient – not for pogroms, as there’s no one to beat, but for protests, equally aimless and violent, involving fights with the police and wreaking havoc on supermarkets. As long as no one has a good reason to exploit this sentiment to their nefarious ends, no one stops protesters from visiting their neighbor Nathan, who never left, since the Pale of Settlement has long since been abolished.