Election results and ruling party tactics

Poland has opted for a change. The participation in the parliamentary elections on October 15 was massive. The reigning conservatives of the Law and Justice party will need to step back, paving the way for a new government that will unite three pro-European parties in a coalition.

The extraordinary nature of the situation became apparent as long, winding queues formed at polling stations. Wrapped in blankets, citizens patiently waited, with some persevering until the late hours, even past midnight, to exercise their democratic right to vote. Although the polling stations were officially scheduled to close at 9:00 PM, those who arrived just in time were still able to participate in the electoral process.

The central election commission clearly did not anticipate such an overwhelming and unprecedented turnout. A remarkable 73% of eligible voters made their voices heard—a number surpassing the turnout in the pivotal year of 1989 when Poland broke away from communism.

The ruling party Law and Justice secured the top spot with 35.4% of the vote, corresponding to 198 seats in the Sejm. Following closely are the “democrats,” comprising three allied formations: Civic Coalition with 30.7% (161 seats), Third Way with 13.514.5% (57 seats), and New Left with 8.6% (30 seats). The Confederation, an ultra-liberal and ultra-conservative faction, rounds off the list with 7.16% of the vote, equivalent to 14 seats.

The ruling party, PiS, left no stone unturned in its bid to secure victory. One such strategy involved orchestrating a referendum in conjunction with the elections. The referendum's questions were framed in a manner designed to invoke fear, alluding to the “sale of national assets” and the influx of “migrants.” However, the public, encouraged by the opposition to boycott the referendum, overwhelmingly chose not to participate, resulting in a 40% turnout and rendering the referendum inconclusive.

The referendum's questions were framed in a manner designed to invoke fear, alluding to the “sale of national assets” and the influx of “migrants”

PiS utilized state-owned media as a platform for the pre-election campaign—news programs served as advertisements for the ruling party. It went to the extent of employing military equipment and soldiers in uniform for pre-election rallies. Pre-election videos were filmed using ministries' funds, and state-owned companies participated in the campaign.

The oil conglomerate Orlen outperformed them all. It artificially lowered fuel prices and, as a result, couldn't deliver fuel on time. Refueling at gas stations became impossible, but one could read calls to participate in the referendum.

It can be noted that in political terms, Poland is divided, but there's nothing new about this. The division was usually marked by the Vistula River. What was considered progressive and liberal was to the west of it, while what was to the east was seen as conservative, linked to the idea of a strong, social state.

In these elections, nearly 50% of the rural areas voted for PiS. The ruling party triumphed even in cities with populations up to 50,000. In larger urban centers, people were more inclined to vote for the Civic Coalition. In the metropolises, the opposition completely overturned the power structure.

In the metropolises, the opposition completely overturned the power structure

In terms of numbers, around 8 million people voted for the Law and Justice party, while about 11 million voted for the “democrats.”

The Future Coalition

To form a majority government, 231 deputies are needed. The “democrats” have 248, so they are the ones tasked with forming the government. This alliance, aimed at sidelining Law and Justice from power, served as the cornerstone of their electoral campaign.

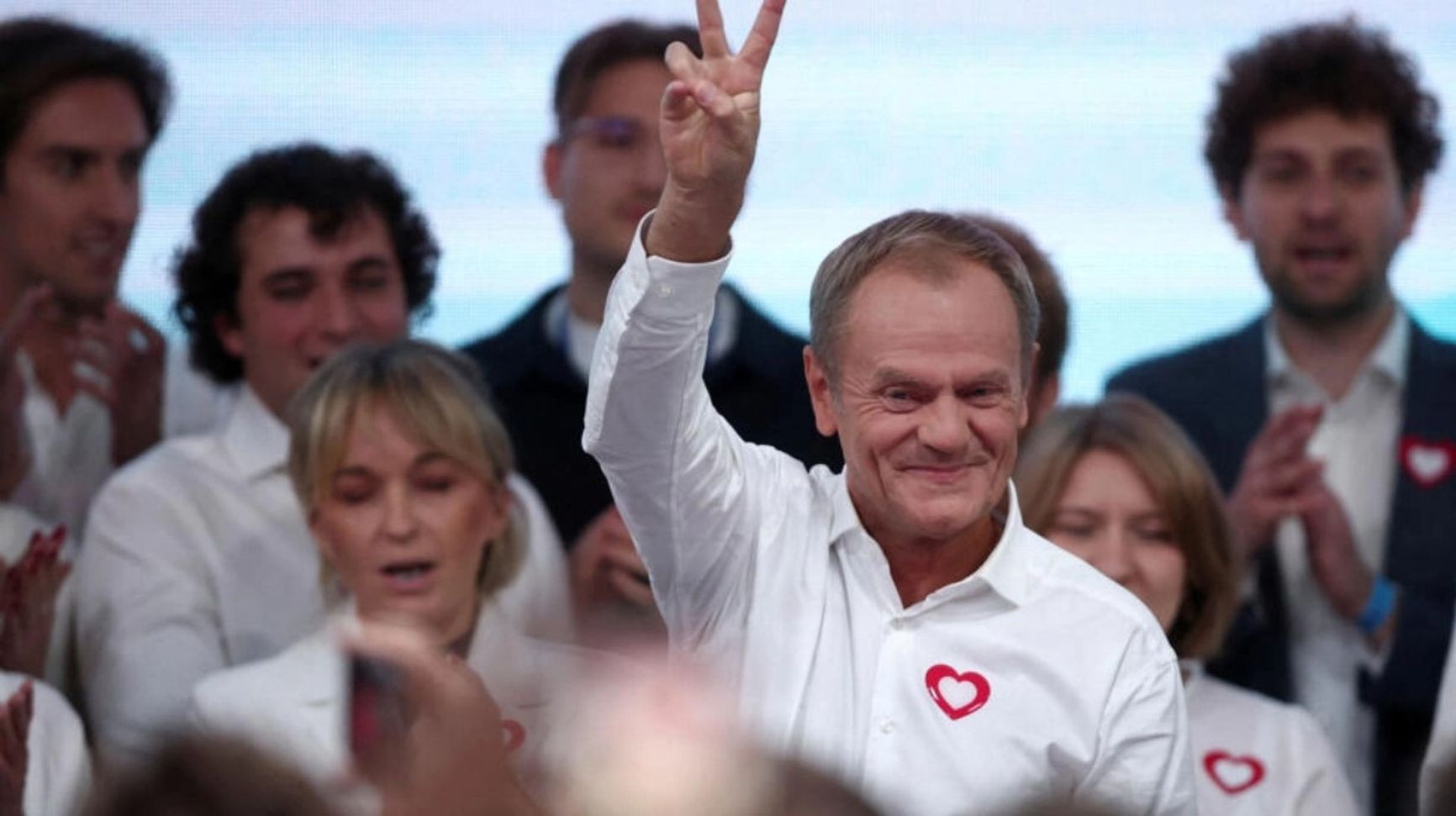

Logic suggests that the leader of the Civic Coalition, Donald Tusk, a 66-year-old veteran of Polish politics, will head the cabinet. Tusk has already led two governments and has also held positions as the President of the European Council and the Chair of the European People's Party. Credit is due to him for the immense work he has accomplished in recent months. He was the driving force behind the campaign and the main architect of its success.

“We did it. Poland has won. The dark streak is over,” Tusk declared after the initial polling results.

Leader of the opposition Civic Coalition, Donald Tusk, Declares Victory in the Elections

REUTERS

Meanwhile, the ruling party also displayed optimism, albeit more restrained and official in tone.

“The polls show the fourth victory in the history of our party,” said Jarosław Kaczyński, the chairman of the Law and Justice party. “We have won,” echoed the hall, filled with ministers and strained smiles. It was clear to everyone: this victory was Pyrrhic, granting no real authority.

Standing side by side with Kaczyński, Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki assured, however, that he is ready to negotiate with anyone regarding the formation of a government. Yet, the coalition potential of Law and Justice is close to nil. The party had hoped to govern the country independently. The only reasonably viable ally could be the Confederation, but the party performed poorly, failing to meet expectations (although polls had promised them over ten percent not long ago).

Some hopes of Law and Justice were pinned on a possible split among the “democrats” and the formation of a joint government with a faction of the Third Way. However, it seems they miscalculated here too. “We will hold you accountable for all your lies, hate, insults, theft, and all your machinations,” responded one of the Third Way politicians to the offer of cooperation.

Fearful and exhausted

What was happening in society? At the ballot box, the “fearful” clashed with the “exhausted.”

The “fearful” were the voters of Law and Justice. Some supporters of the ruling party (the welfare, or cynical, electorate) feared that the new liberal government would deprive them of their benefits. Social benefits would disappear: the “500+” program, a subsidy of 500 zlotys (around 110 euros) per child paid until they reach 18 years of age, regardless of the family's income, and additional (13th and 14th) pensions. Perhaps the retirement age would increase.

Another faction of Law and Justice supporters (the ideological electorate) lived in fear that the victory of progressive parties would lead to a moral revolution, undermine “traditional family values,” and pave the way for the “LGBT ideology.” They were also afraid of fully submitting to Brussels (and Berlin), which would force Poles to accept hundreds of thousands of refugees from Africa and the Middle East. During the pre-election campaign, PiS intentionally fueled these fears.

Law and Justice supporters feared that the victory of progressive parties would undermine “traditional family values,” and pave the way for the “LGBT ideology”

The “exhausted” were the voters of the “democrats,” weary after eight years of PiS rule. They believe that the ruling party is undermining democracy, and the constant disputes between Warsaw and Brussels are a direct path to Poland's exit from the EU. They accuse the ruling party of attempting to undermine the independence of the judiciary, politicize the prosecution, transform state-owned media into pro-government entities, engage in cronyism, appoint “their own people” to state companies, and allocate budget funds to loyal funds and NGOs.

Two massive demonstrations became rallying points for the opposition, where numerous people took to the streets to stand up for their principles. The first one (June 4) was held on the anniversary of the 1989 elections that ousted the communists from power, carrying the slogan “We are proud of democracy.” Several hundred thousand people marched through the streets of Warsaw. However, it was not just “pride in democracy” that drove the high turnout, but the government's plans to establish commissions to “investigate Russian influence in Poland.”

There were suspicions that PiS wanted to place Tusk before such a commission, “judge” him, and prevent him from participating in the elections. This stirred significant public outcry. Even those who disliked Tusk (indeed, the leader of the Civic Coalition had a considerable negative electorate) condemned attempts to persecute him.

The second march, “Million Hearts” (attended by an estimated million people!), took place on October 1. The pretext for its assembly included, among other things, women's rights to legal abortion. Many hospitals in Poland refuse abortions even in life-threatening cases for the patient. As a result, several tragedies with fatal outcomes occurred.

By the way, it was precisely the plan to further tighten the abortion law three years ago that sparked the grand “Black March.” And this was, over the eight years of PiS rule, the only civil protest that was successful.

The battle for voters

In the heat of the pre-election campaign, the “democrats” uncovered a noteworthy segment of silent voters—women around the age of forty, predominantly leaning towards progressive ideals. Advocates for the liberalization of abortion laws, they often remained inactive at the ballot box. In the campaign's final weeks, the opposition strategically vied for these votes, promising to safeguard their rights. Conversely, the ruling party enticed them with an appeal to stability and security.

However, it appears the crucial factor for victory lay elsewhere. Surveys underscored the economy as the prime concern of the population. The opposition saw an opportunity to woo part of the “welfare” or “cynical” electorate away from PiS.

Thus, a fundamental aspect of the pre-election campaign shifted to combatting rampant inflation (up to 20%) and surging prices. In the provinces, a spot-on slogan emerged: “Law and Justice = Rising Costs,” striking a chord with the masses. The “democrats” coupled this with persistent assurances: “We won't take anything away from you—in fact, we'll add.”

In the provinces, a spot-on slogan emerged: “Law and Justice = Rising Costs”

Another crucial point that spurred intense public debate was the migration influx, a threat highlighted by the Law and Justice party. Yet, the opposition skillfully countered this by recalling the tens of thousands of economic migrants from Asia and Africa who entered Poland during Mateusz Morawiecki's government, exposing the porous and corrupt visa issuance system through Polish consular institutions.

Politicians have long realized that emotions influence voters far more than policies. That's precisely why every subsequent campaign in Poland is considered the “most” intense in its history. This one was no exception. It took an unprecedentedly vitriolic tone, with language bordering on vulgarity. A notable slogan adopted by the opposition was “Jebać PiS,” graphically depicted with eight asterisks: ***** ***. The exchanges became personal and venomous, with accusations of betrayal and scathing attacks becoming the norm.

One of the slogans of the opposition in the 2023 elections was “Jebać PiS”

For instance, Jarosław Kaczyński accused Donald Tusk of being a pro-German politician working für Deutschland, branding decisions made during his tenure as “treacherous, disgraceful, and criminal.” During rallies Law and Justice supporters shouted at their opponents: “To Berlin, to Berlin.”

Even prominent figures like film director Agnieszka Holland faced campaign attacks. Her film The Green Frontier, portraying the expulsion of illegal migrants from Polish territory and the cruelty of border guards, became a target. President Andrzej Duda himself joined the campaign against her, quoting a World War II slogan aimed at collaborators: “These films are only for swine(Tylko świnie siedzą w kinie).”

Ending the Polish-Polish conflict

The opposition faces a challenging road ahead. Firstly, they must form a coalition government, finding a way to unite liberals from the Civic Coalition, leftists, and moderate conservatives from the Third Way into a single cabinet of ministers. .

The «Democrats» won not only the Sejm, but also the Senate (66 out of 100 seats), which will certainly make governing easier. But after the government is formed, it will need to figure out how to coexist with the President, a supporter of Law and Justice, who possesses veto power (which the “democrats” cannot override). Law and Justice will transition into a deep, adversarial opposition, making governance more challenging. So, on one hand, the incoming government will face pressure to fulfill their election promises, which involved significant financial commitments in the billions of zlotys. On the other hand, it will be confronted with the practical limitations and actual economic conditions.

The most crucial task, however, is to mend Poland after a grueling campaign. They must convince the “exhausted” and “fearful” that they share more common ground than points of contention.

It appears that Tusk understands this. At the end of the “March of a Million,” he said, “Today, I solemnly swear not only that we will win, hold everybody accountable, correct mistakes, and reconcile, but also that on the day after the elections, I will pledge to you to end the Polish-Polish conflict. By driving out the aggressor, we will eliminate the very cause of the war.”