Former CIA operations officer Marc Polymeropoulos, a 26-year veteran of the agency, served his country in hotspots from Baghdad to Kabul — and numerous clandestine spots in between. In 2017, while on a routine work trip to Moscow — his first visit to Russia — Polymeropoulos fell violently ill with symptoms consistent with Havana Syndrome. Over the next several years, he would struggle to regain his health while fighting his employer for access to the kind of medical care his condition demanded. In this first-person account of that ordeal, Polymeropoulos tells his story to The Insider in his own words.

I was an operations officer for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) for 26 years — the tip of the spear for the United States government, serving in multiple conflict zones. I thought I was a badass, because I was. I walked tall. I felt different from the average Joe. I had failed spectacularly, but succeeded even more. Americans are alive today because of the counterterrorism operations I had been involved in. The words of former acting CIA Director Mike Morell stated it best:

“Marc was one of the finest CIA officers that I encountered in my career… lf people knew the work he has done in the shadows of the Middle East, Europe, and Russia, they would sleep easier at night.”

My basement walls and trophy case are a shrine to the heroes I served with in the Global War on Terrorism. Pictures from Iraq, Afghanistan, and so many other garden spots. Only doing what was required to protect our fellow Americans. I loved my job, and I loved the CIA. It was part of my identity. I woke up every morning and went to sleep each night believing I was part of an elite team, the best of the best.

And then my world came crashing down after what I thought would be a very ordinary temporary duty assignment to Moscow. The organization that I loved turned on me. Chronic pain became my life. Ironically, if the CIA had sent me to one simple doctor’s appointment in early 2018, I would not be here telling this story today. All I wanted after all was to see a doctor. This is my journey.

Moscow, December 2017

In the middle of the night at a five-star hotel in Moscow in early December 2017, I woke with a start. The room was spinning, the vertigo would not stop, and I had tinnitus — terrible ringing in my ears. I could not get up without falling to the floor. I felt like I was going to throw up and pass out at the same time. It was terrifying, and I was in serious distress.

Ironically, I had spent years in war zones for the CIA. I had been shot at, rocketed, and was often in danger. The Middle East, South Asia, and East Africa — these were the places where I actually felt comfortable. I called them my “happy place.” Yet in Moscow, I experienced panic and helplessness for the first time. There was no doubt in my mind that something awful was happening. Back-alley high-risk operational meetings with agents in Afghanistan, or being second in the door on a Naval Special Warfare raid in Iraq, or hunting High Value Targets in places I’d better not mention, were walks in the park compared to the sheer terror I faced that night in the chic center of the Russian capital.

The extreme vertigo abated over the next several days, although I suffered another terrible episode at a famed Moscow restaurant known to the Russian elite. I spent almost the entirety of the final 36 hours of the trip holed up in my Moscow hotel room wondering what the hell was wrong with me. Scared, virtually alone, and in a hostile country. I paid one visit to a local McDonalds, with my ubiquitous Russian surveillance team in tow. I was in agony, but damn if I wasn’t going to battle through the language barrier and order a quarter pounder. Small victories like that one would become a part of my life for years to come. Thankfully, I was able to get on an airplane and fly home to the U.S. after the 10 long days in Russia that changed my life.

What was I doing in Moscow? In December 2017, I was the deputy operations chief for CIA’s Europe and Eurasia Mission Center. I had the unique responsibility of overseeing CIA’s clandestine operations across two continents. As a long-time Middle East specialist, my 10-day trip to Moscow was simply for what we call “area familiarization.”

I was actually excited. I had never been to Russia, which of course was the United States’ greatest adversary during the Cold War. I was just going to talk to the embassy, meet with our then-ambassador Jon Huntsman, and have routine meetings with Russian government officials. This was not work. I told my wife:

“This isn’t Iraq or Sudan. I’m not in disguise, in some safe house with a Glock-19 strapped to my side. It’s a business trip. I’ll wear a suit, and you know, I hate wearing a suit.”

I clearly underestimated the Russian government. They had initially objected to the travel, accusing my colleague and I of going to Moscow for “operational reasons.” We ignored this, as it was a ridiculous charge, and I had departed for the trip in a great frame of mind. I didn’t come back that way.

Coming home

I returned to the U.S. and began a tortured multi-year medical journey, essentially on my own. I saw over a dozen doctors in multiple fields. The menu of specialists included neurologists, infectious disease experts, allergists, dentists, eye doctors, sleep specialists, chiropractors, special massage therapists, and pain, neck and spine doctors. I went through countless rounds of physical therapy, antibiotics, pain medications, steroid injections, and painful plasma regenerative shots in my neck. I have had multiple brain and neck MRIs, CT-scans, and X-rays. I paid thousands of dollars out of pocket for some of the costs that insurance would not cover. Regrettably, I received no assistance from the CIA doctors or staff, save for one young CIA doctor who showed great sympathy towards me. More of his story cannot be told in public, as I believe that he fears for his job at CIA, but I considered him at the time a hero in this awful tale. He knows I am eternally grateful to him.

The end result was the same over and over: the initial diagnosis of Occipital Neuralgia — a migraine headache — that never let up, 24/7, for over four years. It was only in February 2021, after a long struggle with the CIA to obtain the right kind of medical care, that Walter Reed National Military Medical Center’s National Intrepid Center of Excellence (NICoE) diagnosed me with a mild traumatic brain injury (TBI), which they noted was caused by an external exposure event. What a moment that was in my journey. A team of medical doctors and nurses — elite ones at that — actually believed me. But let’s go back to the initial reaction from the U.S. government when I returned from Moscow.

The initial response

Upon my return from Russia, I was examined by the CIA’s Office of Medical Services (OMS). In 2016, multiple U.S. diplomats were subjected to what was then being called an “acoustic attack” while serving at the U.S. Embassy in Havana, Cuba, which meant that the OMS had significant knowledge about these incidents at the time of my examination. Unfortunately, they determined after a few very rudimentary checks that my symptoms were not consistent with those who were injured in Cuba.

And so I continued to suffer. Over several months, I specifically asked for treatment at the University of Pennsylvania, where the U.S. government was sending injured officers from Cuba. Yet my requests were denied repeatedly by senior OMS personnel. It made no sense why they would reject such a simple request for medical care. Sadly, by March and April of 2018, I had developed brain fog and even lost long distance vision to such an extent that I could not drive at times. I remember it like it was yesterday: a trip to Orlando, Florida, to watch my son play in a high school baseball tournament. I was up in the middle of the night, sobbing on my bed. I could not drive, and I could barely see a ball hit out of the infield. By the time of my retirement in July of 2019, I could not go to work for more than three or four hours without experiencing brutal headaches. Yet the repeated reaction of OMS was that my condition was not consistent with the Havana cohort.

I was a mess. I could not work. I was depressed. This was an awful time in my life. Yet it was just the initial stages of my suffering.

Some hope, more despair

It took the intervention of a very senior CIA operations manager in mid-2019, just weeks from my retirement and around 18 months after the incident in Moscow, to finally get OMS senior staff to agree to send me to the National Institute of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland, which was running a one week research study. The study was designed to observe a possible decline in function over time, but did not provide for any treatment options. I was happy to help with such research, but the doctors could not provide me with relief.

The highlight of my time at NIH was quietly giving my doctors and nurses CIA golf balls that I had purchased from our employee store. The agency did not want me to disclose my affiliation to the staff, so this was my silent protest. I became NIH’s favorite patient (in the words of one doctor, who clearly was a golfer). Anyone who knows me well understands that I can find humor even in the darkest moments. If you ever go to NIH and see a CIA golf ball in a doctor’s office, you’ll know that I was there.

From my retirement in mid-2019 through the year 2020, I learned of other cases like mine — officers who had worked on Russia and who were getting hit by similar attacks. I’ll never forget the moment, just as I was retiring, when a longtime friend and colleague returned from an overseas trip. He popped his head in my office and said he needed to talk. He explained what had just happened to him, and the story he told was almost exactly like my Moscow experience. His symptoms were remarkably similar. We looked at each other in stunned silence, only broken with my simple statement: “Dude, what the hell is going on? Who is doing this to us?”

I told him to get to OMS immediately. In my view, it looked like something terrible was happening to our overseas personnel. Today, this officer is suffering from a rare form of cancer (he gave me explicit permission to disclose this). I promised him then and reaffirm it now: to be by his side as he goes through brutal chemotherapy and surgery. I even shaved my head when he lost his hair. But selfishly, I also think of myself. Will such cancers affect other members of this cohort? Am I next? I have sleepless nights worrying about this.

Walter Reed/NICoE

As I continued battling debilitating chronic pain in 2019 and 2020, I requested through contacts at CIA that I receive treatment at Walter Reed/NICoE, the U.S. Government’s leading center for Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI). In fact, my former colleague (who was injured in mid 2019) was receiving care there and was showing some signs of recovery. I wanted to be patient number two, if possible. Yet the answer from OMS and senior CIA officials was always a resounding no. Not only that, OMS senior officers, along with some specific members of the leadership team at CIA, kept repeating that I was simply making the story up for financial gain, as a ploy to receive workers compensation. I heard whispers like:

“Marc is doing this to pad his retirement.”

“Marc had an existing injury.”

“This is just mass hysteria.”

I was horrified hearing these statements. Angry. Betrayed. Dumbfounded. How did they not see I was in constant pain from debilitating headaches? Did they not understand what I had done for our country over the course of my career? Years on end in conflict zones, almost three years without my family after 9/11. My God, the nerve of these Washington-based bureaucrats. Armchair quarterbacks who had never been in the arena. How dare they? I spoke with my official contacts at CIA and again pleaded for care. Their response was that they were working on it, but simply could not make headway.

One officer wrote me the following private message: “Some senior officers should go to jail for treating you like they have.”

I felt an anger growing that I had never felt before. I was injured. I was suffering. I needed proper healthcare. But I had nowhere to turn. Honestly, looking back, I was drinking too much to ease the pain. Jameson was my crutch. I would look at the bottle the next morning, see how much I had consumed, and then try to piece together when I even went to sleep.

My personal relationships were suffering. My priorities in life — my family members — were not getting the attention that they deserved. Of course, my family supported me as I deteriorated, but this was not the norm. I was always the strong one. I was the one who always had the answers and helped my wife and children. Not any longer. I had to rely on them, sometimes for basic assistance. My world was upside down. I was at wits end.

Going public

I went public to plead my case, which was an extraordinarily difficult decision to take given my previous role. Going to the press with such complaints is anathema, even in retirement, as it breaks an unwritten code that the media is not the right venue to air such complaints. I was worried that I might be portrayed as crazy or mentally unstable. Yet I felt I had no choice. I spoke with Julia Ioffe, a journalist at Gentlemen’s Quarterly (GQ) and a true expert on Russia. Julia was widely read in U.S. government circles, as she was born in Russia, speaks Russian, was fearless in her reporting, and had incredible contacts in the country. Thanks to her expertise, she had a near cult-like following within CIA’s Russia House — the operational unit dedicated to tracking Russia — so I was confident that she was the real deal and could tell my story.

I must stress that I did not violate my secrecy agreement in any conversations with Julia for the article, as I spoke only about my own medical journey. Beforehand, I also informed multiple senior CIA officials that I was going public with my case, and I said the same to my old friends and colleagues. None of them objected, because they all saw that I had no other option. A very senior CIA official actually encouraged me to take this step. This person knew that I was getting no traction with my request for care. Their advice was instrumental in my internal debate on going public: “Good, do it, fuck them all.”

The GQ article was published in October 2020, and a media firestorm ensued. I had called out the agency for their poor treatment of me, and the retaliation was severe. Colleagues claimed that lawyers had instructed them to refrain from talking to me, which I found both sad and hardly legal.

“Sorry man, I can’t talk to you anymore. They're coming after you, you're in their gun sights.”

Seriously? What the fuck? I was nauseous reading this. That was from a close friend, someone I’d served with in the trenches. For years. And I have never heard from him again. To this day. Overnight, I went from a superstar operations officer — one of the most decorated of my generation — to a total pariah. I was ostracized. I felt terribly alone. So on top of my physical pain from the headaches, I developed a terrible case of anxiety, which was later formally diagnosed by Walter Reed/NICoE. I could not sleep. I could not eat. I was wracked with fear and anxiety on a daily basis. Lack of sleep dulled my senses. How did I get to sleep at night? With Jameson, in front of the TV.

My wife, who at the time was also a member of the Senior Intelligence Service at CIA, suffered mistreatment at work due to my actions. I felt a terrible sense of guilt, although God bless her, she never blamed me once.

In December 2020, just a month before I went to Walter Reed/NICoE, I hit rock bottom. I had anxiety so severe I could barely make it through the day, and my headaches were nonstop. This was a truly terrible time for me. I could not focus. I could not think straight.

Yet an amazing thing occurred. The GQ article resulted in real movement on the issue of Havana Syndrome, as it frankly embarrassed the agency. Several former CIA directors contacted me immediately after the story broke and personally told me that they had called the CIA’s leadership team on my behalf. They were furious at the agency and could not understand its lack of action or compassion. They communicated to me:

“This is humiliating to the agency.”

“What a basic leadership failure.”

“Why the hell didn’t they just send you to the doctor?”

They were upset that CIA had mishandled my case and, in doing so, embarrassed itself. Then, on October 25, 2020, the Washington Post published an editorial on the issue:

“In GQ magazine, Julia Ioffe recounts the harrowing experience of CIA officer Marc Polymeropoulos, who held a high-ranking position at headquarters. While on an official visit to Moscow in December 2017, he was nearly incapacitated by something that hit him in his Moscow hotel room…The time has come for more openness from the U.S. government — and more help for public servants injured in the line of duty.”

What the hell? This was way out of my comfort zone. An editorial with my name in it. In the Post. One of the most admired news publications on the planet. For a Directorate of Operations officer with 26 years in the shadows, this was beyond surreal. I later met with staff from both the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (SSCI) and the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI), the two oversight bodies in Congress, and I told my story in full. I hired a prominent lawyer, Mark Zaid, who has represented numerous intelligence community personnel. He advocated on my behalf for treatment. Ultimately, the agency relented, and I entered Walter Reed/NICoE’s one month Intensive Outpatient Program in mid-January 2021 — three very long years after suffering my injury in Moscow.

My care, my heroes

Thank God for Walter Reed/NICoE. The program teaches you early on that you are not alone. The 18 specialists I saw over the one-month intensive outpatient program provided an integrated system of care that is simply impossible to find anywhere else. I was joined by several members of the U.S. special operations community, which has been battered by nearly two decades of constant war. The camaraderie of our cohort was inspiring, but seeing firsthand the scars of these American heroes’ sacrifices was sobering.

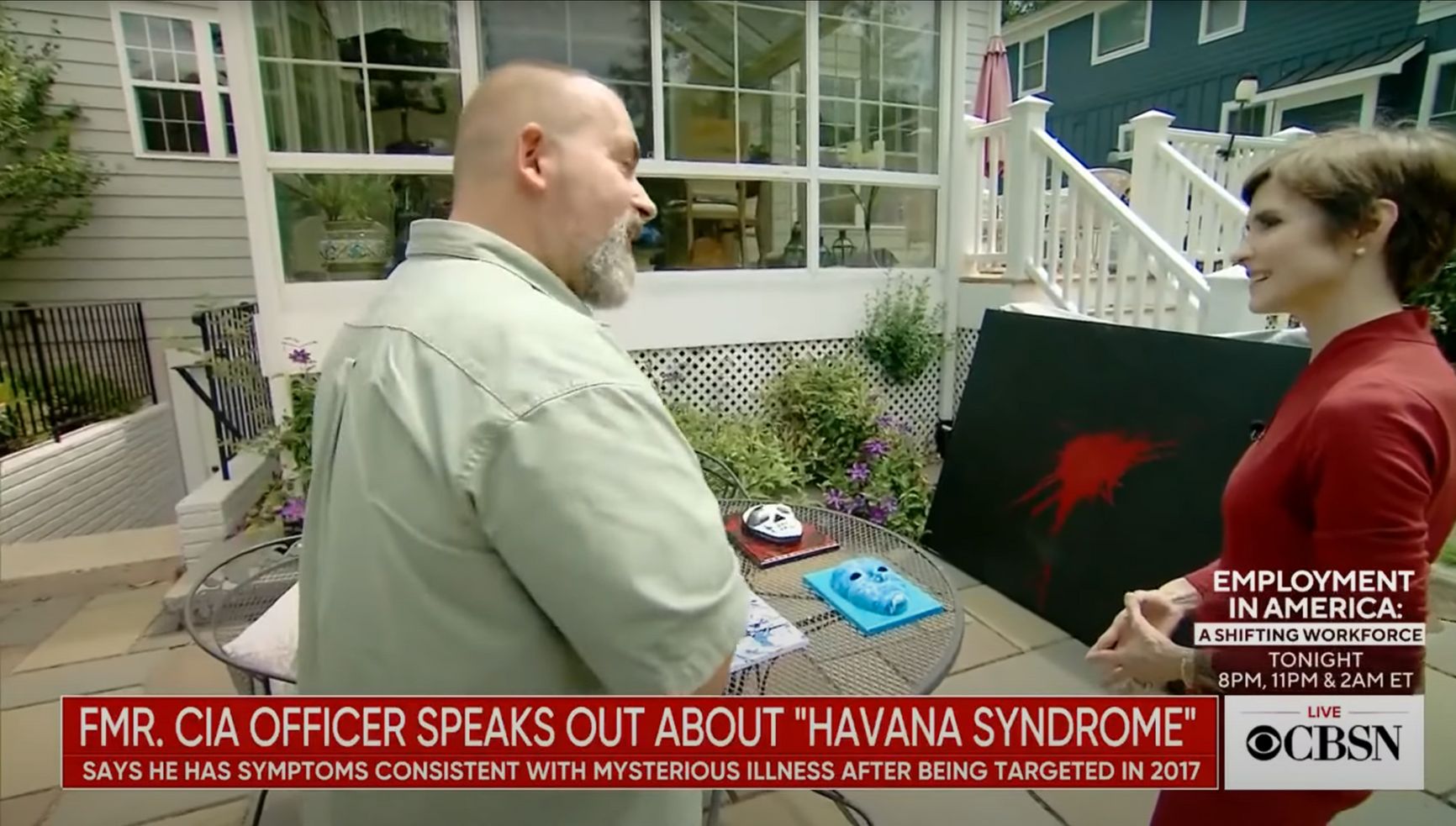

While the requisite medical checks were performed — imaging, blood work, sleep, biofeedback, audiology, psychiatry, and optometry — what was most useful for me was the softer side of healing, one that turns out to be science-based and proven as effective in treating TBI. In 2015, National Geographic ran a cover story about Walter Reed/NICoE’s mask therapy program, in which TBI victims are encouraged by trained art therapists to express themselves by creating masks. I put a great deal of thought and time into mine: a Superman mask that symbolizes my once invincible status as a case officer, serving bravely and with distinction in Iraq and Afghanistan. But that wasn’t all. My mask was attached to a wooden plaque — a plaque with the background of the CIA seal cracked in half, representing how I later had to fight some in the agency in order to obtain proper medical care. An ice pick is drilled through the mask as well, a reminder of the headaches I still suffer from constantly. I also wrote a poem — detailing what my family thought of me for so long — and attached it to the mask, which hangs in Walter Reed/NICoE to this day. The poem contained the line: “I once was your Superman.”

Making this mask and writing the poem was a deeply cathartic experience for me. Along with talking to the resident chaplain and other talented mental health professionals, it helped me begin to heal from the moral injury that I suffered. The art therapist became the most trusted member of my recovery team. I consider her an angel, sent to care for me in one of my greatest times of need. My kids, after I told them about the mask and the poem, sent me a simple, one-line text: “Dad, you are still our superman.”

My kids, after I told them about the mask and the poem, sent me a simple, one-line text: “Dad, you are still our superman.”

Wow. I stared at my cell phone, paralyzed. Then I bawled like a baby. Yet thinking about my journey, this emotional response to my children’s support made sense. I had three critical relationships in my life: with the CIA that betrayed me, and with my wife and my children, who supported and loved me unconditionally. I’m still their superman. Words that I’ll never forget.

I’ll also never forget “Chappy,” the U.S. Marine Corps chaplain at Walter Reed who taught me about forgiveness. Not a trained psychologist or psychiatrist, Chappy instead counseled me about overcoming the moral injury I had suffered. Did those that treated me like a pariah actually deserve forgiveness? No. But the key is to release the anger and disgust anyway. If you do that, they will not win. Amen. Chappy is forever one of my heroes.

And we painted at Walter Reed/NICoE. Boy did we paint. My colleague who also suffered from Havana Syndrome took a giant canvas, painted it in all black, and then threw a bucket of red paint in the center. He called this “The Gunshot.” We howled in laughter as he did this. The release, the feeling of freedom from pain and suffering — it felt good. It signified how we all wished we had been shot, as a gunshot, unlike Havana Syndrome, leaves an undeniable physical wound. I showed the painting during various interviews, including on CNN and CBS News, and “The Gunshot” became our rallying cry.

Marc Polymeropoulos showing “The Gunshot” during an interview with CBS News in 2021

Source: Screenshot of CBS News interview on YouTube ('Former CIA officer shares struggle with "Havana Syndrome"')

There were also physical steps I had to take to get better. Sleep is a prime component of the Walter Reed/NICoE program, as it turns out that a large percentage of TBI victims suffer from sleep apnea. My overnight sleep study during the initial stages of the program was a horror show. I arrived late at night and was getting wired up when the requisite medical checks were performed on me. I don’t know why, but I was scared. I felt claustrophobic. My physical and mental mindset was in the toilet.

The overnight tech took one look at my blood pressure readings and tried not to freak out. 170/100. I laughed. No surprise. I’m a fucking mess. The doctors told him to go forward, but to monitor me overnight. I barely slept during the study. My head was pounding. I was anxious. Morning came, and I don’t think I slept more than an hour. I met the doctors later that day:

“Your Apnea Hypopnea Index reading is at 43. That’s severe sleep apnea. No wonder you are falling asleep while driving and your head is pounding. Good news is, we have a treatment for you. 50 percent of TBI victims have sleep apnea.”

Well, welcome to the CPAP club. The sleep study was a seminal event for me. The use of a CPAP machine, although it doesn’t relieve my headaches completely, nonetheless remains a key component of my ongoing recovery. I am more refreshed and alert than at any time over the last three years.

Physical therapy has also been important, as the nerve damage in the occipital region of my head has caused radiating pain in my neck and back. The specialists there were caring yet tough, and I now have a daily exercise routine that will be critical for my future recovery over the months — perhaps years — ahead.

My self-care may take hours each day just to deal with the pain, but that is my reality, and I accept it. Learning meditation and deep breathing techniques has been as useful as medication for my headaches. I am quite confident that those who worked with me over the years never would have imagined me sitting down every day in a zero gravity chair, using biofeedback techniques to regulate my breath and heart rates. But I do it as part of my regular routine now, and it works damn well. Yes, I bought a zero gravity chair, and I put it down in my basement — right next to a workout bench that has over 400 pounds of weights. My friend Matt, a former SWAT team cop, said it best:

“Marc, time to de-stigmatize some new age treatments… No more macho crap. Get over the P word if you want to take care of yourself.”

Yoga, meditation, deep breathing. I’m all about that now. My wife has practiced this stuff for years. She lovingly quipped:

“Next you’ll be wearing Birkenstocks and a tie-dye shirt while listening to Phish. And drink that kombucha I keep buying for you!”

Hey, why not? I love Jimmy Buffet. Anything to get better. Marc the new-age hippie. P.S. I now love kombucha!

Vindication

Ultimately, I received a formal diagnosis from the Walter Reed/NICoE medical team. Highlights of the actual written report include:

“Diagnosis: Mild TBI..Severe sleep disorder…Anxiety Disorder….Insomnia…Exposure to disaster, war, or other hostilities…Cervical Pain, Cervicogenic headaches…occipital neuralgia….”

This diagnosis was a watershed moment for me, given the long struggles I had faced in asking for proper medical care. I stared at the document and wept. God damn I cried a lot during that month. I literally carried the diagnosis with me, in my pocket, for days on end. My long suffering and misery was no longer a mystery. It was substantiated.

Walter Reed/NICoE embodies everything that is right with America. The U.S. military deserves enormous credit for creating this center to treat its most precious commodity: its people. If only the CIA’s doctors could have done the same.

But that wasn’t the end of the story. I was nervous when my one-month program ended. I had become mildly dependent on the daily routine during treatment. My last journal entries from Walter Reed/NICOE were so telling and powerful:

“I have hope now.”

“But can I do this? Am I ready to be on my own?”

“I feel a sense of loss. The NICoE staff became my family.”

And I must praise my actual family once again. At the end of the Walter Reed/NICoE program, they bring select family members in for joint therapy discussions. My wife attended, as both of the kids were in college.

Every morning at Walter Reed/NICoE, the Navy corpsmen would ask each patient a specific and direct question: “Have you thought of harming yourself recently?” I never thought much about this, because for me, the answer was no. I was miserable, in pain, and a physical and mental wreck, but I did not believe I had suicidal tendencies.

Yet when they asked my wife in the family therapy session if she was worried about me, she broke down crying, saying that she was. She confessed that she had thought about hiding the firearms (already secured in a gun locker) that we held at the house for home defense purposes. I was stunned. I did some serious soul searching after this session. My conclusion is that while I do not believe that I was ever in danger of truly hurting myself, that was not the point. My family was scared that I would. That was the effect that my healthcare journey has had on them. And it was not pretty.

Another reason why I am so grateful for the Walter Reed/NICoE staff and program: we worked on such issues. My wife was relieved to get this off her chest. I took a good hard look at myself, and we agreed that open communication is a must for the future.

The way forward

Director Bill Burns, after his nomination as CIA Director in early 2021, actually called me on the phone. A female voice from an unknown number dryly said:

“Is this Marc Polymeropoulos? This is the Director’s office, please hold…”

I thought it was a prank call at first, and almost hung up. My remaining few friends from the agency — jokers to the core who were alway trying to cheer me up — would be so, so ready to do this to me. Could this be real? After being treated like a pariah for years, it was beyond belief that the CIA Director was reaching out to me. But there he was, on the line.

In our many conversations since then, Burns has expressed extraordinary compassion and empathy for me — two attributes that the former CIA leadership team lacked entirely. On several occasions, he has even had me in to see him at CIA headquarters. I was as candid with him as I am in this article. There must be accountability for what occurred. I asked Burns to ensure that those who treated us in such a terrible fashion were removed from working on this issue, given the damage that they have caused many of us. And of course, treatment must be allowed for all of those who have been injured. I remain encouraged by the current director’s commitment to making this right. I don’t necessarily have the same faith in CIA on the whole, but I do with Burns, who is an honorable public servant. He understands what it means to lead and to care for those that are under his command.

In 2021, several top intelligence and Biden administration officials visited Walter Reed/NICoE. They heard from my doctors that the CIA’s constant refusal of medical care and the history of disparaging remarks had been extremely damaging, both physically and emotionally, to those of us who are suffering. TBI does not get better over time, and Walter Reed/NICoE officials specifically stated to one senior intelligence official:

“You are one suicide away from a big problem.”

I was stunned when I heard this. Shit, I could relate to that. I was also told that the senior officials spent a great deal of time looking at my mask, along with the accompanying poem. Due to the agency’s previous abhorrent behavior in not treating victims, maybe my words meant something. Ultimately, I believe the Biden administration took to heart the need for a change on medical care.

I had a long list of enemies due to my career running counterterrorism operations, but I did not think that individuals within CIA — the organization that I loved (and somehow still do) would have so actively resisted in helping me obtain care. I worked in the darkest corners of the world for decades based on a simple pact that I made with CIA leadership: we serve this country to do the near impossible, and if things ever got jammed up, we expected to be taken care of. In my case, this pact was violated terribly. I believe Director Burns understands that he must continue to rectify this.

The administration he serves under has taken some positive steps. The HAVANA Act was signed by President Biden on October 8, 2021. This legislation provided financial relief to the victims, who in some cases have spent thousands of dollars out of pocket while trying to find treatment on their own. In a press release, Biden stated:

“Today, I was pleased to sign the HAVANA Act into law to ensure we are doing our utmost to provide for U.S. Government personnel who have experienced anomalous health incidents. I thank members of Congress for passing it with unanimous bipartisan support, sending the clear message that we take care of our own… We are bringing to bear the full resources of the U.S. Government to make available first-class medical care to those affected and to get to the bottom of these incidents, including to determine the cause and who is responsible.”

The Agency fights back

Yet the CIA did not go down without a fight. In January 2022, the agency issued an interim report on Anomalous Health Incidents (AHI) — the new moniker for Havana Syndrome. This report was enormously problematic to many of the victims.

In 2021, the U.S. government had issued a mass data call to find out how many of its employees around the globe suspected they were suffering from symptoms consistent with Havana Syndrome, and the exercise reportedly resulted in almost 1,000 claimed attacks. A government task force then “solved” most of these cases while admitting that several dozen of them — the original cohort, in which I was included — were much more difficult to explain. I was very vocal in my discomfort with what was happening, as the headlines in most media outlets insinuated that the agency had essentially discredited the idea that Havana Syndrome was a real issue.

Yet the CIA reportedly did not coordinate this interim report with other elements of the intelligence community. Nor, reportedly, did they receive concurrence from a panel of medical and scientific experts who later released a statement that noted a directed energy attack remained their lead theory as to what had happened to those in my group. In my view, this was yet another embarrassing episode for CIA, and again it was self-inflicted. Once more, a sense of doubt seeped into victims’ minds regarding the agency’s actual commitment to getting to the bottom of the problem. My feelings of betrayal returned. I told my wife:

“They are doing it again. They are going to whitewash everything. They are going to try and embarrass me and others.“

What hurt the most is that I know many of these officers at CIA, those who were behind this malfeasance. They were my friends and colleagues — albeit in the past. How could they do this? In mid-2022, I learned that officers involved in the actual task force investigation of Havana Syndrome had planned to throw a happy hour in their office spaces. It was designed to blow off steam, a normal necessity in the high-stress environment at CIA. Yet what they then suggested doing was shocking and damaging to my core. They actually asked their office mates to act like they had been affected by Havana Syndrome. They essentially said the following: “Come to the party and stagger around, as if you had been hit.”

Whoa. What the hell? I was outraged. Fury burned inside of me. These were my old colleagues, and they were actually mocking our injuries. Mocking me? I thought of calling Director Burns, but there was nothing really that could be done. The agency was not a safe place for me any longer. Instead, several of us ultimately informed the White House of this egregious behavior. I never heard if the happy hour actually occurred, but that did not matter. The damage was done — to me and to the other victims who saw this as yet another betrayal. If former colleagues on this task force were actually mocking us, how could we trust their objectivity in any investigation?

A bit of redemption

While the CIA was questioning the veracity of our claims, Congress and the White House had still been saying all the right things. I even received a personal letter signed by the President. I once was an intern for then-Senator Biden, in 1991, after I graduated from Cornell, and I met him years later during one of his visits to a U.S. Embassy in the Middle East. So perhaps it was fitting when, in 2022, I received the following message from the leader of the free world:

“Dear Marc. Throughout our history, devoted Americans like yourself have dedicated themselves to fulfilling our Nation’s promise to its citizens and the world. I know it has not been easy, and I thank you for your commitment to service — from your internship days in my Senate office to your outstanding career at the Central Intelligence Agency. It truly matters. Keep the faith. Joe Biden.”

What an extraordinary acknowledgment that our government needed to do right by those who were injured in the line of duty. The letter sits in a glass case in my living room — a constant reminder to me that some U.S. Government officials perhaps care. The president included.

Now, however, it is up to the various agencies to enact provisions of the HAVANA Act. Based on experience, and given the history of Washington’s response, I do remain somewhat skeptical. But I certainly hope that they take to heart the intent of Congress and the words of President Biden to indeed provide financial relief to victims who suffered so terribly. For those junior and mid-level Department of State and CIA officers who face a lifetime of medical issues, this compensation will make a difference.

It certainly did for me. On Sunday, Feb. 26, 2023, I received a call from Mark Zaid, my lawyer, who simply said:

“You are going to get it.”

I nearly dropped the phone. Mark, who has been so important in my battle, who has stood by me through thick and thin, passed on news that I could not have believed would have been possible mere months earlier. The agency was going to approve my HAVANA Act compensation package. My tough exterior really does mask a hidden sentimental side (ask my family, I cry during “Peanuts” Christmas specials), but I’m sure that Mark was not ready for me to break down right there on the phone. I could barely hold it together as I thanked him. And then I hung up and sobbed for an hour.

Five years I had battled. The stigma. The betrayals. And now, the government was admitting what the doctors at Walter Reed had put on paper was true. I suffered from a TBI. It was not based on pre-existing conditions. My doctors had medical evidence of what had occurred. And after all of that, the CIA was finally acknowledging a workplace injury.

Despite the CIA’s seeming acceptance of reality, on Mar. 1, 2023, the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) produced a memo in both classified and unclassified versions. In sum, the DNI assessed that it was “very unlikely that a foreign adversary was responsible for AHIs.”

In multiple interviews, I pointed to Aristotle’s principle of noncontradiction, which states that opposites cannot simultaneously be true. I received compensation for a TBI that I suffered in Moscow, in the line of duty. Yet the DNI states that, in effect, nothing happened to me. Enough said.

Where do we go from here?

There must be accountability for what occurred inside the U.S. government over the past six years. I leave that to the various oversight organs, including the Inspector Generals inside the national security agencies and the intelligence oversight committees on the Hill, who now have a keen understanding of the lies and misdeeds that occurred between 2016 and today. This drive for accountability that we victims now demand is a necessary but unpleasant evil, as there was so much wrong that was perpetrated on dedicated public servants. Officers like myself needlessly suffered.

I was called to testify on separate occasions in front of HPSCI and SSCI — the Congressional oversight committees. It was an unclassified hearing with the potential to define the issue for generations, and as my heart pounded, I proudly, forcefully delivered the following statement:

“I hold several officials at the CIA directly responsible for my suffering. TBI does not get better over time. I suffered, for years, because of them.”

And I named them. Fuck it. Why not? Why did I go down this road? Because it took me years to finally get the healthcare I deserved, and even with this treatment, pain remains a major issue in my life. In the view of many of the victims, senior officials from this time period must be held accountable. The CIA workforce is watching. The victims will not rest until there is accountability. I certainly will not rest.

We must also continue to advance a healthcare paradigm in which injured officers are immediately provided care. CIA Director Burns deserves credit for making real and significant changes to our medical protocols, insisting that officers are taken seriously and cared for. But more needs to be done. The 2022 Intelligence Authorization Act called for a review of the standards by which CIA hires OMS doctors. That Congress felt it necessary to insert such language is quite a damning indictment of OMS. I would hope that the unfortunate history of the CIA response to Havana Syndrome does motivate change within our medical staff.

Next, we must display the same level of commitment to this issue that we did for the counterterrorism (CT) fight after September 11th. The CT paradigm that proved so successful — detect, disrupt, and deter terrorist attacks on Americans — must translate into how we protect our personnel presently located in the line of fire. I recall hundreds of officers working on just one terrorist threat during my time at CIA. We moved mountains to protect the American people. That same ethos must be brought to bear on the issue of these attacks. I believe Director Burns tried to do so, but was opposed by pockets of narrow-minded, bureaucratic, and litigious thinking that remain inside CIA. My understanding is that the investigation is shifting to the Department of Defense. That is probably ideal, given that, sadly, the CIA failed in its efforts. Public and Congressional support for these efforts are key, as is a push from the White House.

Lastly, the national security establishment must start thinking about what happens when we do find out who was behind these attacks, for I believe that they were acts of war. I speak to many of my colleagues overseas in various U.S. government agencies. They are worried when they see their colleagues going down, often injured without hope of recovery, all around the world. They see six years of incompetence and inaction, and they ask, “is it safe to serve overseas?” Make no mistake, according to press reports, there are children of U.S. diplomats who were permanently injured by these attacks. Some officials are scared, and others are angry — both at whoever is doing this, and also at our government for failing to do enough to push back. The only right answer to these questions will be found when we determine culpability and aggressively respond against the adversaries who committed these attacks.

Russia is not our friend

So let us address the 60,000 pound elephant in the room — who did this? Personally, I believe it is the Russians. They have a record of working on such directed energy weapons. That is not in doubt. There is plenty of open source information that documents this. Moreover, the Soviet Union and then later Russia have subjected our diplomats in Moscow to unspeakable harm over the last several decades. My old colleague at CIA, John Sipher, stated in a 2022 interview:

“The Russian security services were known during the Cold War to flood the U.S. Embassy in Moscow with electromagnetic radiation…they concentrated microwaves and electronic pulses against the Embassy in an attempt to eavesdrop against US typewriters, computers, and conversations.”

He added in a separate interview:

“The Russians have taken actions that have impacted the health of American diplomats and intelligence officers.”

Moreover, Russian President Putin has no compunction about violating norms of acceptable behavior. We can see this from the recent events in Ukraine, where Russian forces have committed heinous war crimes on an apocalyptic scale. Putin himself is a war criminal. Furthermore, as noted in press accounts, the U.S. government reportedly used unclassified geofencing tactics to determine that Russian intelligence officers had been in the vicinity at the time of some of the attacks. I have no knowledge of the investigation, as I have been out of government since 2019. But based on these media reports, I would say there is a strong circumstantial case that Russia is responsible.

I am also heartened that open source investigative firms are gearing up to tackle the issue. Given the success of organizations such as Bellingcat to uncover Russian malfeasance around the world, I am hopeful that this line of inquiry will bear fruit. In speaking with my retired colleagues who were the leading experts in Russian intelligence, there is little doubt in their minds who the culprit is. Senior U.S. intelligence officials have told the victims in private that they share this view. I do believe the story of Havana Syndrome lies somewhere deep in the restricted files of the Russian intelligence services. Perhaps one day an agent or a defector will bring such documentation to the CIA. I hope there is a big reward out there for whoever chooses this course of action.

This is a part of me, whether I like it or not

I speak on a daily basis with the victims. It is tragic to hear their stories of illness, anxiety, depression, sadness, and betrayal. Yet I know I have a role to play. One victim, who was injured in Central Asia, contacted me and said that he had escaped further harm by “getting off the X,” meaning that he quickly moved away from the area as the attack was occurring because he immediately recalled my story. He told me:

“If not for you, I think we all — including my wife and young child — would have been severely injured. You helped save us. Thank you. Thank you.”

I think of his comments every day. These words remain critically important to me. I had done some good. After the whole terrible ordeal I had gone through — the fights with the agency, becoming a pariah, my physical and mental anguish — I had actually helped a fellow officer by going public.

So here I am in 2024, an advocate for healthcare. In my view, this is the Agent Orange, Gulf War Syndrome, and Burn Pits of our time. These other incidents of mysterious health issues — which were also at first denied by the U.S. government — turned out to be both real and terribly harmful to Americans who were serving their country. Public service is the most noble of professions. If we want the next generation to serve, we must demonstrate a commitment to care for those hurt in the line of duty. Quite simply, America owes it to those that stood up and said “send me,” and who now need critical care.

As for me, after a career spent serving my country in some of the hottest spots on the globe, I’m doing my best to keep up the good fight.

“What the hell do you do every day?” My 83-year-old father asks me? “Are you bored?”

Ha, what a question! The answer is an emphatic no. My headaches have become less severe, but even after continued treatment, I only have around two hours of bandwidth each day to undertake serious intellectual activities. I am very cognizant of my limitations and have to be strong in respecting what my body can and cannot do. I start my day with a coffee, and I exercise religiously, as this thankfully makes the pain dissipate. Walks and weight lifting — the two Ws — are my daily ritual. I visit my daughter, who has moved back to Northern Virginia after finishing college. I watch my son play baseball at a small college in Virginia. And I’m responsible for making lunch — my wife has given me this task. She is my rock in this ordeal. Words cannot express my love for her, sticking with me through truly awful times.

I still have a couple retired friends from the agency. We hang around at the local watering hole, “The Vienna Inn,” famous for the aging spies who sit on the barstools and for the chili cheese dogs that are served by the dozen. I talk all the time to my best friend, who actually introduced me to my wife, and who never wavered in his support. We once ran the streets together, from Baghdad to Beirut. Now, in retirement, we can only reminisce about operations that once saved the world — and argue about the fate of the Boston Red Sox. Those others who also bravely stood by me in the worst of times — and you all know who you are — you define what friendship is all about. I’m somewhat broken. But I am not beaten. I will not let Havana Syndrome get the best of me.

The few hours in the day that I can really concentrate are spent talking about a book I wrote, “Clarity in Crisis: Leadership Lessons from the CIA.” Published in June 2021 by Harper Collins, it has taken me from the television studios of MSNBC’s Morning Joe to being the “Person of the Week” on Fox News Sunday with Chris Wallace. I volunteer for some charities, and I also write for various media outlets. In 2022, I was named a non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council. My specialty is in hybrid warfare: how countries utilize unique means, below the threshold of an actual shooting war, to harm their adversaries. What an appropriate topic for me and my terrible experiences with Havana Syndrome.

A good friend, a former member of the U.S. special operations community and leader of the Atlantic Council project, said it best when asking me to come onboard. As I noted before, there is always humor in the darkest of times. I must try to smile and laugh, as best I can. He quipped:

“Hey man, your head was zapped by the Russians. Who better than you to tell the story of hybrid warfare?”

Cover photo: Screenshot of CBS News interview with Marc Polymeropoulos, published on YouTube on June 14, 2021.