Earlier this month, Vladimir Putin joined the host of authoritarian leaders who traveled to Tianjin, China, for the Shanghai Cooperation Organization’s annual summit. Twenty years ago, the SCO could have been dismissed as a marginal regional forum. Today, however, it has grown into an expanding tool of Chinese influence, closely intertwined with Russia and increasingly attractive to states seeking an alternative to Western dominance. Beijing now presents the organization as a stage to rehearse its vision of global governance. That vision is no longer limited to economic megaprojects. China has launched a “Global Governance Initiative,” and even if the real impact of this diplomatic maneuvering remains uncertain, Beijing’s ambition to become a pillar of a new international order is prominently on display.

Exactly twenty years ago, a colleague of mine — then a liaison officer between UNDP Beijing and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) — lamented his tiresome duty to attend what he called “absolutely useless SCO meetings and banquets of mostly retired diplomats.”

Back then, in 2005, the SCO was little more than a footnote: six members, a low profile even in China, and an agenda narrowly defined as fighting the “three evils” of terrorism, separatism, and extremism. Russia’s participation was less a preference than a necessity, while Beijing’s ambition was simply to bind its Central Asian neighbourhood into closer security cooperation. The SCO was a useful umbrella to reassure nervous neighbours about China’s rise, but hardly more than that.

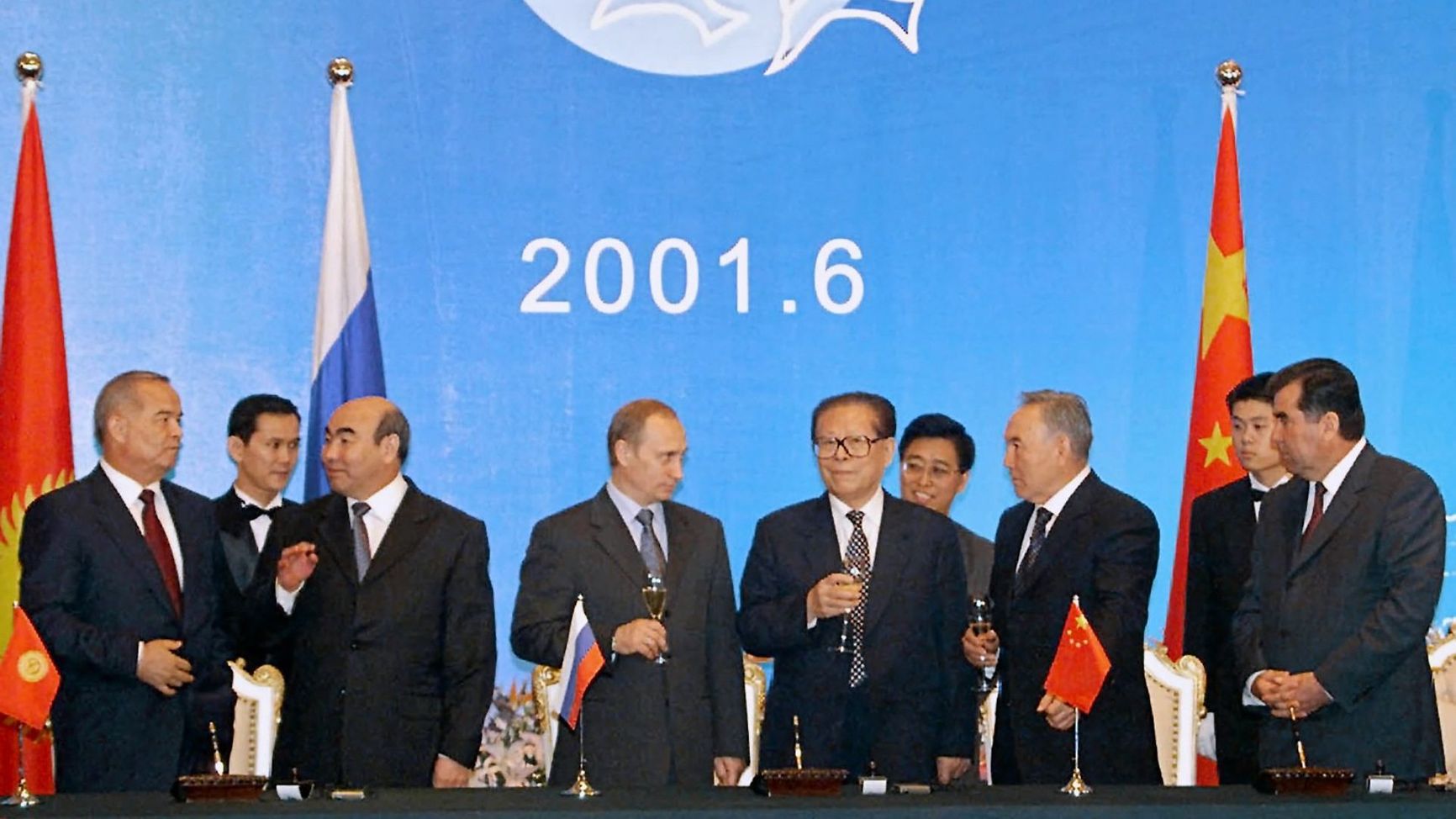

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization was established in 2001 largely as a regional club.

Photo: Sputnik / Sergey Velichkin

For the next decade, the organisation ticked along quietly with joint anti-terrorist exercises, border consultations, and intelligence exchanges. Few in Beijing, Moscow, or Central Asia expected it to become more than a regional security forum. Its first real leap came only in 2017 with the enlargement that brought in India and Pakistan — an audacious move that risked paralysis, given the new members’ bitter rivalry and Moscow’s tilt toward New Delhi. Analysts warned that the expansion might destabilise the SCO from within. Yet even after the bloody 2020 Galwan Valley clash, India remained inside. The SCO endured, demonstrating a resilience that surprised many.

The SCO’s first real leap came only in 2017 with the enlargement that brought in India and Pakistan.

Momentum continued. By 2023 Iran had joined, and in 2024 Belarus followed. Today, the SCO counts 10 members, 2 observers, and 14 dialogue partners.

From Europe to the Pacific

In purely geographical terms, the once modest Central Asian club now stretches from the Pacific to Europe and the Middle East. Its composition is a mosaic: nuclear powers like China, Russia, and India; sanctioned states like Iran; fragile neighbours like Pakistan; and resource-rich Central Asian republics including Kazakhstan. This diversity could indeed have proved paralyzing. Instead, it has given the SCO a peculiar flexibility, making it a forum in which rivals can still find minimal common ground.

Against this backdrop, the Tianjin summit in August-September 2025 showcased how far the organisation has come. China orchestrated an impressive media spectacle, preceded by months of preparatory forums on AI, digital economy, agriculture, and foreign affairs. State media dubbed it the “SCO Plus” summit, with twenty national flags displayed instead of ten — an unmistakable message that the SCO is no longer a regional club but a platform with global relevance.

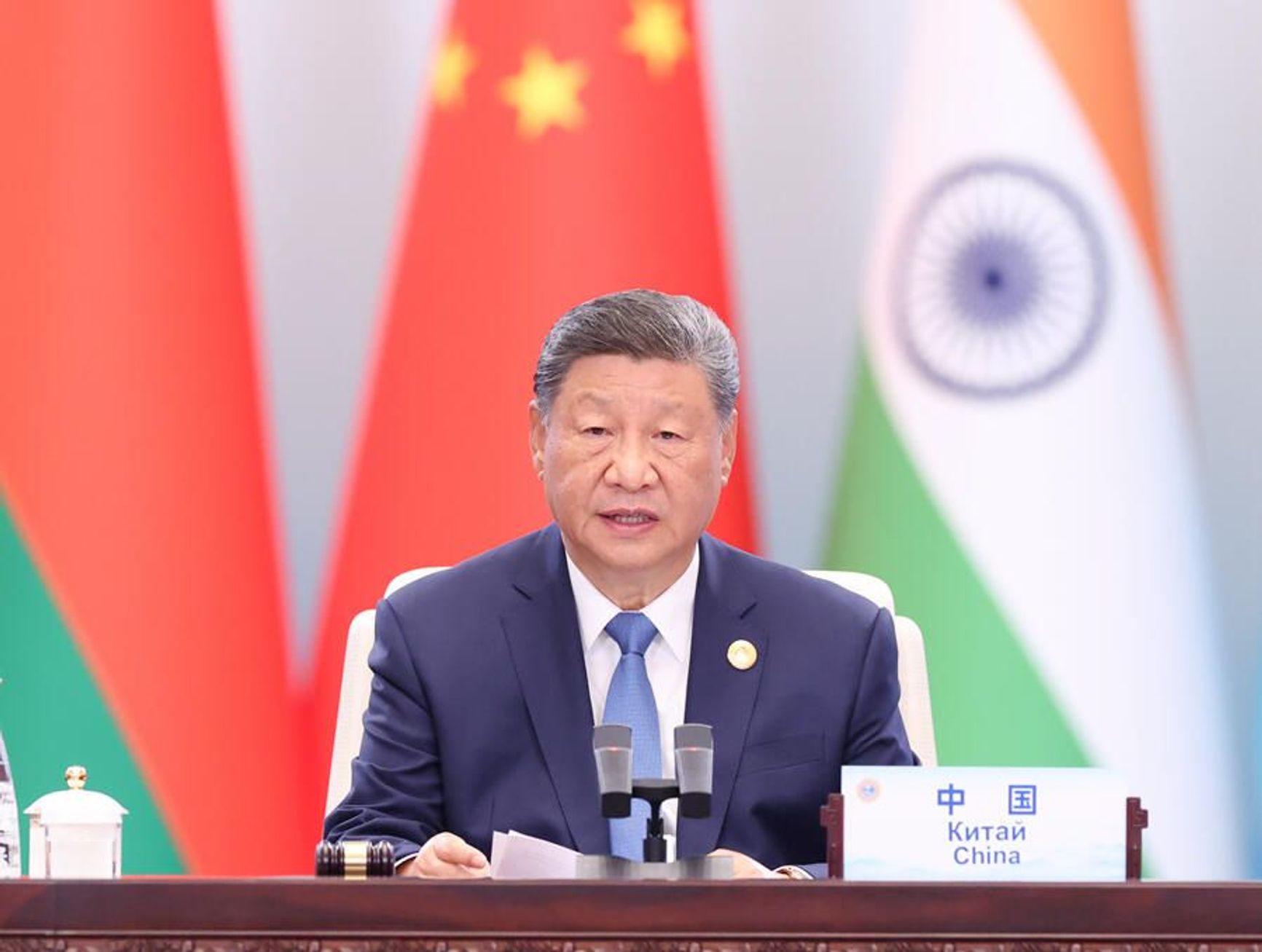

China’s Xi Jinping used the occasion to unveil a new Global Governance Initiative, hailing the SCO as a pioneer of “true multilateralism” and stressing that the organisation embodies the “non-Western” values of consultation and sovereignty.

Chinese President Xi Jinping speaks at the “SCO Plus” meeting in Tianjin, a port city in northern China, on Sept. 1, 2025.

Photo: Xinhua

Expectations before Tianjin had been high. Observers anticipated China would use the summit to demonstrate its institutional maturity, showcase financial deliverables, and extend symbolic outreach beyond the group’s membership. Many expected progress toward an SCO Development Bank, increased local-currency trade, and hints at further enlargement. There was also speculation that Beijing would launch a “big idea” to elevate the SCO onto the stage of global governance.

In all these areas, outcomes broadly matched predictions. The summit endorsed a ten-year development strategy, confirmed work toward a Development Bank, and agreed to expand bilateral settlements in national currencies — steps clearly designed to chip away at the dominance of the U.S. dollar. The “Global Governance Initiative” was the rhetorical centrepiece, positioning the SCO as part of a wider Chinese push to reframe the rules of international politics.

In other areas, results were more modest. Hopes for breakthroughs on energy corridors or green transition policies did not materialise, as rhetoric around connectivity outweighed substance. Security cooperation remained limited to familiar counterterrorism pledges and intelligence-sharing, with no new mechanisms put in place.

Yet even this was significant: despite tensions between China and India, hostility between India and Pakistan, and Russia’s continuing war in Ukraine, a consensus was achieved. For Beijing, this was the real victory: proving that the SCO can function as a platform even when its members are divided elsewhere.

Why does Xi Jinping need the SCO?

What, then, does China want from this partnership? At the most basic level, Beijing sees the SCO as a vehicle to stabilise its strategic environment, bind its neighbourhood into frameworks that suit Chinese interests, and project itself as a source of institutional innovation.

Unlike the UN or G20, the SCO is a space China can shape directly, without Western vetoes. The organisation offers three layers of utility: security stabilisation in Central Asia, economic corridor-building linked to the Belt and Road, and norm-setting authority in global governance debates.

Russia’s role is crucial in this design. For Beijing, Moscow is less a natural partner than a necessary co-anchor. Russia’s military weight and UN Security Council status give the SCO political clout, while Moscow’s estrangement from the West makes it a willing collaborator in experiments with local currency settlements, alternative banking structures, and energy coordination.

China, in turn, offers Russia an economic lifeline that sustains its relevance in Eurasia. The partnership is symbiotic but asymmetrical: neither side fully trusts the other, but both see clear benefits in staging unity within the SCO. Xi’s reluctance to endorse Russia’s war in Ukraine in the joint communique spoke volumes about the limits of alignment. Russia may be a co-founder, but in today’s SCO it is clearly the junior partner.

Moscow’s estrangement from the West makes it a willing collaborator in China’s economic experiments.

This logic connects directly to China’s broader game with the United States. Rather than confronting Washington head-on, Beijing has sought to construct parallel institutions that erode U.S. dominance by offering non-Western states credible alternatives. The SCO, alongside BRICS and the Belt and Road Forum, is part of a latticework of organisations through which China can portray itself as the hub of non-Western multilateralism. By expanding membership and deepening functional agendas — finance, digital standards, AI cooperation — the SCO undermines U.S. claims to represent the “international community” and positions China as the architect of a different global order.

Inside China, scholars and policymakers describe the SCO’s trajectory in three ways. First, as a process of institutional deepening: moving from a discussion forum to a club capable of throwing around its economic weight through projects such as the planned Development Bank. Second, as a civilisational project: an embodiment of “Eurasian values” like sovereignty and non-interference, contrasted with what Beijing presents as Western interventionism. And third, as an experiment in pragmatic gradualism: not an EU-style union or a NATO-type military alliance, but a flexible hub where states can cooperate selectively without entering into binding commitments. In Beijing’s vision, the SCO should evolve less into a rigid bloc than into a “networked platform,” expandable and malleable while remaining subject to Chinese diplomatic choreography.

Two decades ago, the SCO could be dismissed as a marginal regional forum. Today, it is an expanding instrument of Chinese influence — symbiotically tied to Russia, increasingly attractive to states weary of Western dominance, and positioned as a stage on which Beijing rehearses its vision of global governance. This ties in with Beijing’s original concept of the global landscape: China is the “inner lands” and is entitled to receive tributes from the “outer lands.” Whether its new ambitions translate into durable power remains to be seen. But to ignore the initiative now would be to overlook one of the quietest yet most deliberate experiments in the potential construction of a post-Western international order.

The article was written by Doris Vogl, a lecturer at the University of Vienna and a teacher at the ICEUR School of Political Forecasting. This semester, as part of a 10-week online course, she and her colleagues at ICEUR will examine the forces currently reshaping the global order. More information can be found here.