Russian GRU Unit 29155 is best known for its long list of murder and sabotage ops, which include the Salisbury poisonings in England, arms depot explosions in Czechia, and an attempted coup d’etat in Montenegro. But its activities in cyberspace remained in the shadows — until now. After reviewing a trove of hidden data, The Insider can report that the Kremlin’s most notorious black ops squad also fielded a team of hackers — one that attempted to destabilize Ukraine in the months before Russia’s full-scale invasion.

Content

The world is not enough

“Billingcat”

WADA and beyond

Who watches the ArmsWatcher?

Spy v. spy

Hatching the eaglets

Preparing for war

Double life, second family

The target list

For members of Russia’s most notorious black ops unit, they look like children. Even their photographs on the FBI’s “wanted” poster show a group of spies born around the time Vladimir Putin came to power in Russia. But then, hacking is a young man’s business.

In August 2024, the U.S. Justice Department indicted Vladislav Borovkov, Denis Denisenko, Dmitriy Goloshubov, Nikolay Korchagin, Amin Stigal and Yuriy Denisov for conducting “large-scale cyber operations to harm computer systems in Ukraine prior to the 2022 Russian invasion,” using malware to wipe data from systems connected to Ukraine’s critical infrastructure, emergency services, even its agricultural industry, and masking their efforts as plausibly deniable acts of “ransomware” – digital blackmail. Their campaign was codenamed “WhisperGate.”

The hackers posted the personal medical data, criminal records, and car registrations of untold numbers of Ukrainians. The hackers also probed computer networks “associated with twenty-six NATO member countries, searching for potential vulnerabilities” and, in October 2022, gained unauthorized access to computers linked to Poland’s transportation sector, which was vital for the inflow and outflow of millions of Ukrainians – and for the transfer of crucial Western weapons systems to Kyiv.

More newsworthy than the superseding indictment of this sextet of hackers was the organization they worked for: Unit 29155 of Russia’s Main Intelligence Directorate of the General Staff, or GRU. In the past decade and a half, this elite team of operatives has been responsible for the Novichok poisonings of Russian ex-spy Sergei Skripal and Bulgarian arms manufacturer Emilian Gebrev, an abortive coup in Montenegro, and a series of explosions of arms and ammunition depots in Bulgaria and Czechia.

Unit 29155 is Russia’s kill and sabotage squad. But now they were being implicated for the first time as state hackers. Moreover, the U.S. government made a compelling case that Unit 29155 was engaged in cyber attacks designed to destabilize Ukraine in advance of Russian tanks and soldiers stealing across the border – if this were true, it would mean that at least one formidable arm of Russian military intelligence knew about a war that other Russian special services were famously kept in the dark about. This hypothesis is consistent with prior findings by The Insider showing that members of 29155 were deployed into Ukraine a few days before the full-scale invasion.

In August 2024, Unit 29155 – Russia’s kill and sabotage squad – were being implicated for the first time as state hackers

The Insider has spent a year investigating the hackers of Unit 29155. Relying on a trove of leaked emails, social media posts, phone records, and, crucially, unprotected server logs and left-behind burner emails and disused VK and Twitter accounts, we can for the first time reveal the origin, goals, and evolution of this obscure cadre of cyber operators. As with almost everything Unit 29155 concerns itself with, the hackers were devoted to prosecuting Russia’s military objectives in the information space relevant to two physical battlespaces: Ukraine and Syria. And as with everything Russian intelligence operatives do, they waged a hybrid war against the rest of the world, often unconcerned about the distinction between friend and foe.

They waged false-flag hacks meant to create enmity between Ukraine and its Western allies. They recruited an out-of-work Bulgarian journalist to spread disinformation, based on hacked-and-leaked data belonging to Russian-friendly governments, about Western security assistance to Kyiv and to anti-Assad Syrian rebels. In the years preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, they actively disseminated a series of fake stories about the allegedly nefarious activities of U.S.-funded biolabs in Georgia, Ukraine, and a collection of other states in Russia’s periphery.

Corrupt, adulterous, plagued by internal discord and jaw-droppingly sloppy tradecraft, and frequently at odds with their masters in the Russian Ministry of Defense, these hackers were emblematic of the dysfunctional unit they served. Amid their occasionally stunning successes, they left a trail of embarrassing failures.

The world is not enough

Unit 29155’s hacking department appears to be the youngest cyber unit within the GRU system, whose other ornaments include Unit 26165, or “Fancy Bear,” which was publicly implicated in interfering in the U.S. Presidential Election in 2016, and Unit 74455, or “Sandworm,” which caused the most devastating and costly cyberattack in history the following year. On May 21, a consortium of NATO intelligence services, including multiple U.S. agencies, released a Joint Cybersecurity Advisory naming Fancy Bear as an acute cyberespionage actor that had expanded “its targeting of logistics entities and technology companies involved in the delivery of aid” to Ukraine since late February 2022. No mention was made of Unit 29155 in this regard.

Leaked email correspondence and chats in left-behind social media accounts reviewed by The Insider show that this recondite hacking team started out as a lone operator in 2012 – one focused on spreading disinformation and conducting subversive activities in Azerbaijan and elsewhere – under the initiative of the then-GRU director, Igor Sergun.

Unit 29155's hacking department started out as a lone operator in 2012 – one focused on subversive activities in Azerbaijan and elsewhere – under the initiative of the then-GRU director, Igor Sergun

Timur Stigal, an ethnic Chechen blogger living in Dagestan, was seconded to the unit at that time. Stigal told Voice of America (VOA) in July 2022 that his legal name was Timur Magomedov and that he was born in the Chechen village of Kurchaloy. His son Amin is one of the six Unit 29155 hackers named and indicted by the United States, but The Insider has found no digital evidence that Amin, who was a 19-year-old gamer when he was indicted, was involved with any cyber operations activity on behalf of the GRU. Amin called the charges “complete nonsense and lies” in an interview with VOA, and Timur, who now goes by “Tim,” has stated that his son was misidentified.

There may be some merit to that claim.

In January 2024, Tim Stigal, also known by his hacker alias “Key,” was himself indicted by the U.S. Justice Department on multiple counts of wire fraud, wire fraud conspiracy, computer fraud extortion, access device fraud, and aggravated identity theft targeting customers of three unnamed U.S. corporations, dating from 2014 to 2016. No connection was made between the Stigal père and any Russian special service. The father’s named offenses were couched as those of a career cyber criminal. Among other things, Tim Stigal cloned people’s credit cards while he was employed by a Russian intelligence service, the indictment said.

Indicted simultaneously and mentioned in the same Justice Department press release was another Russian national named Aleksey Stroganov, or “Flint,” whose alleged banking crimes dated back to 2007. Although not explicitly characterized as one of Stigal’s accomplices or co-conspirators, Stroganov’s U.S.-based targets were in the same New Jersey jurisdiction and included the luxury department store Neiman Marcus and the arts and crafts retail chain Michael’s.

"Flint" with St. Petersburg governor Alexander Beglov

The indictment of Amin Stigal in connection with Unit 29155’s hacking team, which was unsealed in September 2024 (eight months after his father’s separate charges were publicized in a different state), made no mention of their filial connection. Nor did either federal prosecutor’s office explicitly refer or allude to Tim Stigal as the founder of Unit 29155’s cyberoperations department. So Amin, just 19 at the time he was indicted, may well have fallen prey to a misattribution of his father’s digital fingerprint, or may have been an unwitting helper to his father’s malign activity. The Insider did not find any digital traces of links between Amin Stigal and other hackers from Unit 29155.

In 2008, Tim Stigal self-published a book, The Grail of Iman, about the practice of foreign exchange trading in accordance with the Koran and Sunnah, the Islamic customs of the Prophet Mohammed. He’s also dabbled in romantic poetry. Stigal’s still-active finance blog is titled “The World is Not Enough,” an allusion to the eponymous James Bond film, whose logo it co-opted.

Stigal entered the national spotlight in 2011 after he accused Vladislav Surkov, the “grey cardinal” of the Kremlin, of waging an “unofficial war” in the Caucasus, particularly Chechnya. Stigal took to Twitter to inform the Russian president at the time, Dmitry Medvedev, that Surkov’s entourage allegedly tried to extort $300,000 for arranging a meeting between Stigal and Surkov. Medvedev replied: “I showed your tweet to [Vladislav Yurevich] Surkov. Call him at the reception. Tell him who is pulling money.”

Stigal entered the national spotlight in 2011 after he accused Vladislav Surkov of waging an “unofficial war” in the Caucasus, particularly Chechnya

In 2012, Stigal founded a local Dagestani chapter of the pro-Kremlin youth activist movement Nashi and organized a flash mob lobbying for the renaming of the central square in Makhachkala, the capital of Dagestan, to “Putin Square.”

Stigal’s pleas to be given a chance to prove his mettle and fealty to Moscow were ultimately heeded by someone in the intelligence apparatus. He was already cooperating closely with the FSB's Department of Military Counterintelligence when — no later than June 2014 — he joined Averyanov's black ops GRU team. That month, Stigal was issued a cover identity bearing the pseudonym “Danila Magomedov” (using his original surname) and an April 1978 birthdate that fell around four-and-a-half months earlier than his actual one. Leaked telephone data shows that in February 2016 Stigal used this cover identity to register a SIM card. No later than 2017 he began traveling internationally on a passport in Magomedov’s name and in the same numerical sequence as the pseudonymous documents of other known operatives of Unit 29155, such as Alexander Mishkin (“Alexander Petrov”) and Anatoliy Ruslan Chepiga (“Ruslan Boshirov”), the two Skripal poisoners.

The passport of Stigal's cover identity shares the numerical sequence with the pseudonymous documents of the two Skripal poisoners

The FSB’s Department of Military Counterintelligence is known for its contacts with hackers and fraudsters, whom it enlists to commit crimes at arm’s length from the Lubyanka. After making the move over to Unit 29155, Stigal managed to recruit Igor Voroshilov, a freelance commercial hacker, and Alexey Stroganov, Stigal’s fellow U.S. indictee.

Stroganov, records analyzed by The Insider show, served two years in prison in Russia in the mid-2000s for his online criminal activities, but after receiving an early release, he came under the protection of state authorities. From 2014 to 2020, his group continued stealing bank card data not only in Russia but also in the European Union and the United States.

Voroshilov, who had a long prior symbiotic relationship with the FSB, recruited to Unit 29155 a young hacker and ex-con from Rostov named Yevgeny Bashev. Bashev later became the operator of the targeting server for the unit’s cyberattacks on Ukrainian and Western infrastructure in the lead-up to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Tim Stigal’s greatest triumph as a state hacker may well be one that no cybersecurity expert or intelligence agency ever associated him with the GRU, much less its black ops unit. A close second was his successful penetration of QNB, Qatar‘s largest state bank, in May 2016.

Tim Stigal’s greatest triumph, aside from the fact that no one ever associated him with the GRU, was his successful penetration of Qatar‘s largest state bank in 2016

This operation exfiltrated 1.5 gigabytes of data, including customer information containing bank credentials, telephone numbers, payment card details, and dates of birth. Unit 29155, under Stigal’s direction, leaked all of it online and structured the dump in such a way as to draw the focus to the financial dealings of the Qatari royal family and their government’s intelligence operations. At the time, Doha was financially and military backing a consortium of Islamist rebel groups opposed to the Syrian dictatorship of Bashar al-Assad, including ones, such as the Faylaq al-Rahman Brigade, with which the GRU would later directly negotiate local ceasefires and evacuations from the Damascus suburbs in pursuit of ending the years-long civil war in favor of Assad’s regime.

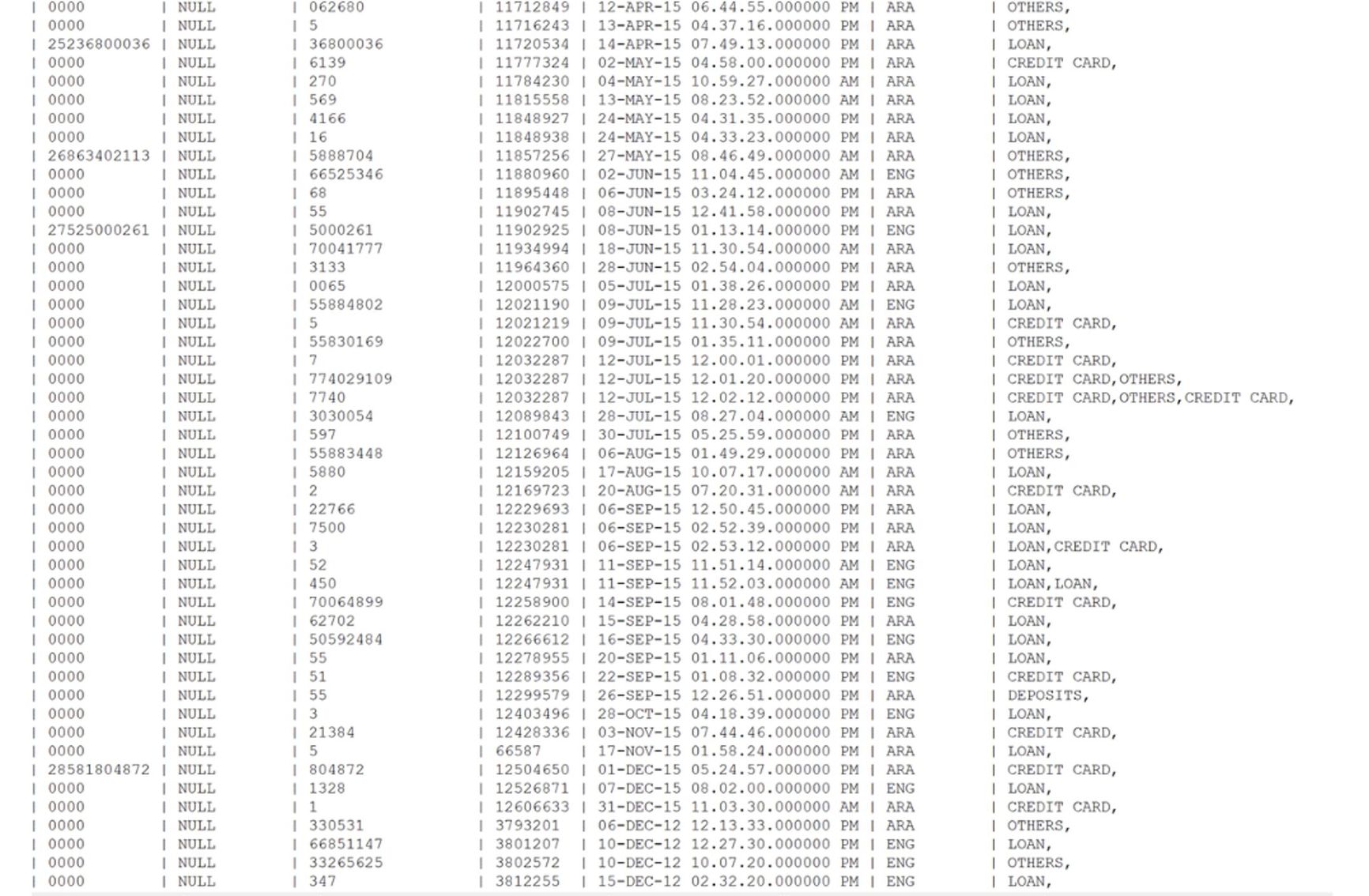

Screenshot of the Qatari bank hack found on the GRU server

Responsibility for the QNB hack was claimed on social media by an account ostensibly run by a Turkish far-right group, @bozkurthackers. It was a false attribution, as Unit 29155 reports and hack logs examined by The Insider demonstrate. The account @bozkurthackers, like many other false-flag Twitter handles that Unit 29155 came to rely on, was run single-handedly by Tim Stigal. To date, this operation has never been publicly linked to Russian military intelligence.

Another false-flag hack perpetrated by Stigal’s team sought to stoke tensions between Ukraine and Poland. In July 2016, Unit 29155, now posing as members of Ukraine’s ultra-nationalist Right Sector movement, leaked hacked Polish telecom data, as well as medical records of Polish military staff, and posted abusive messages at Polish government officials, accusing them of eyeing the potential annexation of Western Ukraine. “To Poland government: You want Lviv? Suck our dick! You will get [another] Volhynia,” the account tweeted, referring to a gruesome massacre of Poles by Ukrainian nationalists in Eastern Galicia in 1943.

![Screenshot of Unit 29155's impersonation of Ukraine's Right Sector. One tweet reads: “To Poland government: You want Lviv? Suck our dick! You will get [another] Volhynia.”](/images/yLQjJAquvp431wf7DgfkmisNqOWeQIsqAduGqsEmnRA/rs:fit:866:0:0:0/dpr:2/q:80/bG9jYWw6L3B1Ymxp/Yy9zdG9yYWdlL2Nv/bnRlbnRfYmxvY2sv/aW1hZ2UvMzQxODkv/ZmlsZS1mODkwMWE1/Yjg4NTI4NDkyYmMx/NDc3MTBhYTQ3ZDFl/Mi5wbmc.jpg)

Screenshot of Unit 29155's impersonation of Ukraine's Right Sector. One tweet reads: “To Poland government: You want Lviv? Suck our dick! You will get [another] Volhynia.”

Right Sector played a marginal role in the 2014 Euromaidan Revolution, but the Kremlin placed a great emphasis on the supposedly “fascist” or “neo-Nazi” origin of the widespread protest movement that toppled pro-Russian Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych’s government and set Ukraine on a path of pro-Western integration. That revolution was punctuated by Russia’s illicit seizure of the Crimean peninsula and the fomenting of a dirty “separatist” war in Donbas, east Ukraine, spearheaded by veteran officers of the GRU and Russia’s Federal Security Service, or FSB, and undergirded by heavy conventional weapons systems such as the Buk anti-aircraft platform that shot down MH17 in July 2014.

The impersonation of an account allegedly used by Right Sector yielded results, as some Polish government officials reacted in anger.

Stigal’s talents as a digital provocateur went further: his team registered yet another false-flag account, this time of a (non-existent) Polish chapter of the hacktivist group Anonymous. That account began verbally abusing Ukrainians, declaring Ukraine to be “a Polish land,” and claiming to have hacked Right Sector.

The timing of this cyber-operation was also critical: the data was leaked to the international media on July 7, 2016, exactly one day before the NATO summit in Warsaw at which Ukraine’s future in the transatlantic military alliance, as well as NATO backing for the new transitional Europhile government in Kyiv, took up much of the agenda.

According to a Polish security official who spoke to The Insider on the condition of anonymity, “This hack was a total f*ck-up in Poland. The case went to the lowest possible prosecutor's office and was given to the police, who did absolutely nothing. It was dead from the start: no culprit was ever found.”

“Billingcat”

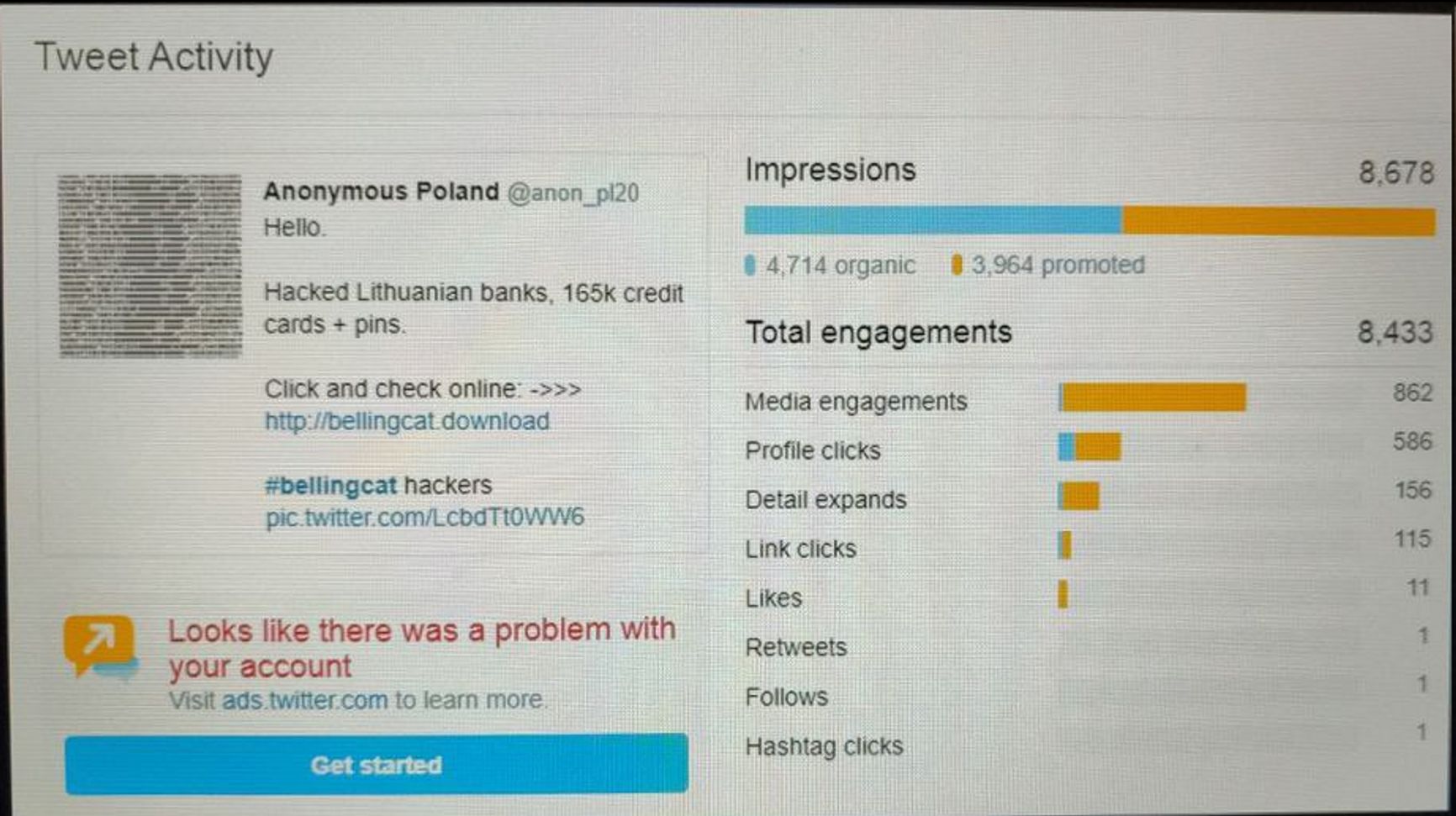

A third false-flag hacking operation – one recycling the already deployed false-flag “Anonymous Poland” account – targeted Bellingcat, the open-source investigations platform, which over the past ten years has partnered extensively with The Insider on stories related to Russian intelligence plots – and to those carried out by Unit 29155 in particular. In 2017, however, when this cyberoperation got underway, the existence of Unit 29155 was still unknown, even though its operatives had already carried out unsolved bombings across EU and NATO territory for at least five years.

Under the guise of “Anonymous Poland,” Stigal’s team leaked stolen credit card data associated with Lithuanian banks, then falsely alleged that the hack had been committed by Bellingcat cyber intruders – rather than by GRU operatives – who were working in league with Anonymous Poland.

Screengrab of one of the false Anonymous Poland accounts dashboard showing the reach of the Bellingcat smear campaign. Found in the disused burner email used for reporting by Unit 29155

Unit 29155 didn’t just use Bellingcat to try to sow division between Poland and the Baltics; it also made efforts to drive a wedge between the outlet and Ukraine.

Stigal’s hackers doxed the names and photographs of children of Ukrainian soldiers then serving on the frontlines in a not-so-frozen war with Russia in Donbas. The Anonymous Poland cutout again falsely attributed the hack to Bellingcat, which reported the account multiple times to Twitter. The platform nevertheless ruled that the actions of Anonymous Poland constituted no violation of its terms of service.

Stigal’s hackers doxed the names and photographs of children of Ukrainian soldiers then serving on the frontlines in a not-so-frozen war with Russia in Donbas and falsely attributed the hack to Bellingcat

Finally, Unit 29155 drew up a list of targets connected to the real Bellingcat, albeit misspelled as “Billingcat,” a frequent mistake by Russian speakers who often falsely attribute the group’s name to “phone-billings.” The Insider recovered it from text files sent between and among the hackers via a left-behind email address that was used to register a burner account on VKontakte, Russia’s Facebook equivalent. The email and the VKontakte direct messages were apparently used by members of Unit 29155 for reporting purposes. The list of targets is divided into “leaders,” “investigators,” and “sympathizers,” referring to employees of Bellingcat and various social media accounts known to amplify the outlet’s work. Several of the people on this list have confirmed to The Insider that they were targeted by spear-phishing campaigns at around the same time.

WADA and beyond

While the “@pravysektor” and “@pravsector” accounts were swiftly identified as fraudulent and removed by Twitter, the @anonpl and @anon_pl20 accounts remained active for years, and Stigal’s team, emboldened by the intrigue, confusion, and infighting it fostered with the Polish and Ukrainian campaigns, used it to deploy hack-and-leak operations multiple times in the months to follow. Some of the leaks made public via these accounts have previously been attributed to other GRU hacking units such as FancyBear, leaving open the possibility that Unit 29155 collaborated with other compartmentalized cyber teams or sought to promote the work of their colleagues in military intelligence.

An archived page of the account @anpoland run by Stigal shows some of the leaks promulgated by Unit 29155 in September 2016. The leaks include “Detroit Police department files” (using hashtags #StopFBI #Revolution), “Docs from strategic air command and Boeing KC-10,” the U.S. paralympics team, and the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), which had exposed the “systematic state-sponsored subversion of the drug testing process prior to, during, and subsequent to the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics.” The Independent Person Report, released by WADA in July 2016, resulted in the banning of hundreds of Russian athletes from subsequent international sports competitions.

Cybersecurity experts and the FBI attributed the hacking of WADA in 2016 to seven GRU officers attached to Unit 26165, some of whom traveled to foreign cities to conduct close-access hacks of anti-doping and sporting officials’ computer networks.

Who watches the ArmsWatcher?

As with other GRU hacking teams, Stigal’s sought out and relied upon external actors to disseminate information illegally obtained. One of Unit 29155’s helpmeets is Dilyana Gaytandzhieva, a Bulgarian journalist once celebrated for her fearless door-stepping reportage. Chats examined by The Insider show Stigal ostensibly first contacted Gaytandzhieva via Twitter, leaking to her and encouraging her to publish a data set of cargo airline traffic and inventories allegedly found in the Azerbaijani Embassy in Sofia. The hacked dataset allegedly showed that Silk Way Airlines, an Azerbaijani private cargo company, was transporting U.S.-commissioned weapons shipments using diplomatic flights.

To provide a layer of deniability, similar to the stratagem used in the Polish information operation, Stigal set up a false-flag Twitter account under the name @anon_bg. This one called itself ”Anonymous Bulgaria.” The account was activated in April 2017 and initially retweeted authentic tweets from the Anonymous hacktivist group, thus lending the impression that it, too, was meant to be a national wing of the international movement. The first original tweet by Anonymous Bulgaria was posted on June 27, 2017. It included a link to the hacked and leaked mail correspondence – “backup files + diplomatic emails” – from the “Azer Embussy [sic] in Bulgaria.” The hashtag given was for “Military Cargo on ‘SilkWay’ for terrorists,” referring to the national airline of Azerbaijan.

One of Unit 29155’s helpmeets is Dilyana Gaytandzhieva, a Bulgarian journalist once celebrated for her fearless door-stepping reportage

The ostensibly “initial” approach by Stigal via @anon_bg was made on June 27, 2017, via Twitter direct message. On the face of it the exchange reads like a hacking group contacting a journalist to offer an interesting trove of data. The journalist responds that she is interested, and proposes a meeting with the leaker, promising anonymity. The hackers respond that a meeting is out of the question and that all data is available in the data leak.

However, this “initial” chat is laden with inconsistencies and appears to have been staged to provide deniability for Gaytandzhieva in the event of scrutiny. Gaytandzhieva’s last message on that day asked for a call, a request that went unanswered. The chat ended there.

However, subsequent exchanges between @anon_bg and other Twitter users show that the communication between Stigal and Gaytandzhieva continued on some other platform, and likely long predated that DM chat.

In many other interactions with journalists and bloggers contacting the fake Anonymous account, Stigal tells each of them to contact Gaytandzhieva for further information and for “the complete dataset that she has.” In a long direct message exchange with Narine Grigoryan, an official then working in Armenia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Stigal tried to convince Grigoryan to send a protest note to the Bulgarian ambassador in Yerevan in connection with “Bulgaria selling weapons to Azerbaijan to kill innocent Armenians.” This was in the aftermath of Azerbaijan’s four-day war with Armenia over the disputed enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Stigal tried to convince an Armenian foreign ministry official to send a protest note to the Bulgarian ambassador in Yerevan in connection with “Bulgaria selling weapons to Azerbaijan”

On July 3, 2017, Stigal wrote to Grigoryan: “It's very important to call (sic) of bulgarian ambassador in Armenia and take over him protest note about military help to Azerbaijan. It’s reason for interrupting peace negotiations in region. From o[u]r side we try to control export of military goods from Bulgaria. We need some precedents to press on government and PM Borisov,” referring to Boyko Borisov, Bulgaria’s prime minister at the time. (This message came just two years after members of Unit 29155 had poisoned the Bulgarian arms trader Emilian Gebrev, who had been exporting munitions to Georgia and Ukraine.)

In a reply to Grigoryan’s question, “How can I help?” Stigal wrote, “Ask Dilyana, she’s a good girl,” and encouraged Grigoryan to try to contact Gaytandzhieva via Telegram.

Stigal even attempted to cultivate the Armenian into cooperation by citing her attractiveness. “You very beautiful and intelligent woman [sic] its a pity that not my wife,” he DMed her.

Grigoryan wrote back that she was acting “for my country but I appreciate the compliment.” She then asked Stigal how he knew what she looked like. “Trust me,” he answered, “you are insanely beautiful.”

The compliments fell short of achieving their goal when Stigal asked Grigoryan to help Gaytandzhieva “organize a protest in front of the Azerbaijan embassy in Sofia.” Grigoryan bowed out by saying she could not take part in anything of that nature. This disclosure from Stigal, however, hinted at Gaytandzhieva’s role as more than a scrivener for the GRU. She was now, according to her handler, acting as a provocateur on the service’s behalf.

On July 3, 2017, six days after Stigal’s “initial” approach to Gaytandzhieva on Twitter, she published an exposé based on the data hacked by Unit 29155 in the Bulgarian daily Trud (“Labor”). Notably, this was the only English-language article published by Trud, suggesting that the goal of the investigation was to reach an international audience while benefiting from the credibility of an established local media organ.

Six days after Stigal’s “initial” approach to Gaytandzhieva on Twitter, she published an exposé based on the data hacked by Unit 29155

“At least 350 diplomatic Silk Way Airlines (an Azerbaijani state-run company) flights transported weapons for war conflicts across the world over the last 3 years,” Gaytandzhieva’s story opened. “The state aircrafts of Azerbaijan carried on board tens of tons of heavy weapons and ammunition headed to terrorists under the cover of diplomatic flights.” She attributed her information to an “anonymous Twitter account – Anonymous Bulgaria.”

As for her claim that the weapons and ammunition, which included rocket-propelled grenade launchers, were destined for “terrorists,” Gaytandzhieva tenuously connected one consignment of a shipment of RPGs to a company called Purple Shovel, LLC, a Virginia-based weapons contractor hired by the Pentagon for its Train and Equip program to back Syrian rebels committed to fighting ISIS. In 2015, a 41-year-old American employee of Purple Shovel and former U.S. Navy veteran, Francis Norwillo, was killed when an RPG went off at a military range near the Bulgarian village of Anevo. (Most of the hardware obtained by Purple Shovel, a Buzzfeed investigation found, was decades-old and in disrepair.) Gaytandzhieva asserted in her piece that the RPGs acquired by Purple Shovel were not used by anti-ISIS Syrian rebels attached to the Pentagon program.

“In December of [2016], while reporting on the battle of Aleppo as a correspondent for Bulgarian media,” she wrote, “I found and filmed 9 underground warehouses full of heavy weapons with Bulgaria as their country of origin. They were used by Al Nusra Front (Al Qaeda affiliate in Syria designated as a terrorist organization by the UN).”

That such weapons might have been captured by Al Nusra, which fought frequently with rival rebel groups during the Syrian civil war, is nowhere entertained in Gaytandzhieva’s investigation. Nor does she explain how she knows who the intended recipient of any of the consignments mentioned in her story were. She makes other unsubstantiated assertions that Western partners were intentionally arming ISIS because certain weapons found in the Silk Way manifests eventually wound up in the hands of the jihadist franchise known to raid state military installations and overtake rival insurgents in Syria and Iraq.

Russian state propaganda, needless to add, trafficked in exactly the same dark accusations during Operation Inherent Resolve, the U.S.-led coalition to defeat ISIS – the Kremlin claimed that the West was secretly underwriting the very terrorists with which it was at war.

During the 2016 U.S. presidential contest, Democratic Party correspondence hacked by FancyBear was laundered through the cutouts Guccifer 2.0 and DCLeaks before making its way to Wikileaks. Unit 29155 followed a similar pattern when amplifying the work of their agent Gaytandzhieva. Subsequent tweets on @Anon_bg focused almost exclusively on promoting the Azerbaijani hack archive as well as covering Gaytandzhieva’s investigation. The account garnered attention mostly from conspiracy theorists and obscure far-right American bloggers, in addition to other Russia-linked websites. However, it was followed by journalists from many legitimate media outlets such as CNN and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. Unit 29155 proudly reported these stories back to Moscow as proof of their successful operation.

The fake account set up by Unit 29155 was followed by journalists from many legitimate media outlets such as CNN and the OCCRP, which the unit proudly reported back to Moscow as proof of their successful operation

By late August 2017, Gaytandzhieva was no longer working at Trud. Accounts of the departure differ, as she publicly claimed she was fired over the investigation, an allegation denied by the publisher. In an article published on August 25, 2017, she claimed that a “Bulgarian National Security officer called and invited me to their [sic] office, where I was interrogated over my source of investigative journalism. I told them [sic] how I got that confidential document, but refused to unveil the source, since I am not obliged to do that.”

Following her laundering of the Azerbaijani Embassy hack, Gaytandzhieva’s involvement with Unit 29155 became more systematic. Tasked by Stigal’s operatives, she undertook several reporting trips.

In early January 2018 and later in September the same year, for instance, she traveled to Georgia to report on alleged U.S. biolaboratories operating out of the American Embassy in Tbilisi, a bogus claim that has since been repeatedly debunked. On December 29, 2017, just days before Gaytandzhieva’s trip to Tbilisi, Tim Stigal returned to Moscow from the Georgian capital using his false “Magomedov” passport, leaked travel records show. Reports from Stigal in the abandoned VKontakte account show that on his trip he met at least one of the “witnesses” that Gaytandzhieva subsequently used days later in her alleged investigation. Additionally, on her second trip to Tbilisi Gaytandzhieva was accompanied by Asyaa Ivanova, a Bulgarian residing in Russian-occupied Crimea and working for the GRU-run website Newsfront.

Gaytandzhieva’s initial report from Tbilisi was published on a little-known English-language website called NaturalBlaze.com

The second trip yielded a fake news report, initially broadcast on Syrian government-linked satellite TV channel Al Mayadeen TV and republished by a cluster of websites, mostly in Russia and Africa. The Tbilisi “investigations” became the first installment in Gaydandzhieva’s long series of baseless allegations regarding the existence of U.S.-funded laboratories in the former Soviet Union, which she claimed were weaponizing pathogens.

In 2018 Gaydandzhieva was kicked out of a European Parliament conference in Brussels for pushing her GRU-backed pet conspiracy, then bragged about it on Twitter two weeks after Russia invaded Ukraine. Starting from the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, she took to publishing articles with headlines such as “Pentagon biolab discovered MERS and SARS-like coronaviruses in bats” – echoing “Operation Denver,” one of the KGB’s most viral (as it were) active measures during the Cold War, which convinced millions around the world that AIDS was a biological weapon invented at Fort Detrick.

In 2018 Gaydandzhieva was kicked out of a European Parliament conference in Brussels for pushing her GRU-backed pet conspiracy, then bragged about it on Twitter two weeks after Russia invaded Ukraine

Internal chats seen by The Insider show that Unit 29155 considered its biolabs series to be the crown jewel of its cyber information operations. The series was used to justify tens of millions of dollars in additional state funding for Unit 29155.

The falsehoods contained in Gaytandzhieva’s reporting became the bedrock of official Russian government claims about malign U.S. scientific research into infectious diseases, all in the lead-up to the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. As with most tropes of Russian disinformation, this one was circular: a GRU-concocted lie, fed and amplified by a GRU agent in the West, was picked up and regurgitated by Russian officials – in this case, Gen. Igor Kirillov, the head of Russia’s radiological and chemical weapons military unit, who was assassinated in Moscow in 2025 by Ukrainian intelligence.

The falsehoods contained in Gaytandzhieva’s reporting became the bedrock of official Russian government claims about malign U.S. scientific research into infectious diseases

As Gaytandzhieva grew in importance for 29155’s hack-and-leak and disinformation operations, it became awkward to search for new media partners to publish her dubious reporting. So Stigal had the bright idea for her to start her own fake news resource.

Under his guidance and instruction, Gaytandzhieva registered a website in 2019 called ArmsWatch.com. The site became a dumping ground for other hack-and-leak products that Unit 29155 wanted to make public. Whether by accident or design, the site's aesthetic and design mirror that of Bellingcat, an obsession – and hacking target – of Unit 29155.

The website ArmsWatch.com became a dumping ground for hack-and-leak products that Unit 29155 wanted to make public

In many cases, ArmsWatch publications correlated with Unit 29155’s efforts to cover up its own mounting crimes by trying to discredit journalistic investigations – including those by The Insider – into how the Russian black ops unit’s operations were carried out. These include the unmasking of Skripal-poisoners Mishkin and Chepiga, and of the Unit 29155 team behind an earlier attempt to kill not just Bulgarian arms dealer Emilian Gebrev, but also his son and factory manager.

Gebrev’s company EMCO, as The Insider previously disclosed, was stockpiling weapons and ammunition at the Bulgarian and Czech depots Unit 29155 blew up beginning in 2011. Those Russian covert operations continued through 2015 in an effort to impede the flow of weapons to Moscow’s adversaries. These were: the pro-Western government of Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili, whose military was still reeling from its devastating summer war with Russia in 2008 and quietly attempting to rearm; the post-Yanukovych Ukrainian military, then struggling to recover territory taken by Russian-backed forces in Donbas; and anti-Assad rebel groups in Syria.

In an effort to sow doubt around the conclusion that Sergei and Yulia Skripal had been poisoned with the Russian military-grade nerve agent Novichok, Gaytandzhieva suggests the victims’ blood samples may have been tampered with and that they were in fact drug addicts who succumbed to a Fentanyl overdose.

To sow doubt around the conclusion that the Skripals had been poisoned with Novichok, Gaytandzhieva suggests they were in fact drug addicts who succumbed to a Fentanyl overdose

Each of Gaytandzhieva’s stories ended with the disclaimer: “I am an independent journalist and do not work for governments or corporations.”

Spy v. spy

Between September 1 and September 15, 2019, ArmsWatch published a multiple-part series under the heading “The Serbia Files.” The report cites what appear to be authentic leaked documents but reaches the unsubstantiated conclusion that a U.S. proxy was deliberately funnelling Serbian-made weapons to ISIS and al-Qaeda. “These documents expose the biggest lie in the [sic] US foreign policy,” Gaytandhzieva argued, repeating her well-rehearsed refrain as a GRU agent, “officially fighting terrorism while secretly supporting it.”

Leaked chats reviewed by The Insider reveal that these documents were passed to Gaytandhzieva by Alexandar Obradovich – a Serbian employee of the weapons manufacturer Krušik.

Unlike other target countries in Unit 29155’s sights, Serbia is an ally of Moscow, making this GRU information and influence operation stand out from others published by ArmsWatch. Obradovich was arrested three days after Gaytandhzieva’s third installment, “Leaked arms dealers’ passports reveal who supplies terrorists in Yemen,” was published on September 15, 2019. Gaytandzhieva had disclosed, in that article, that her source had been a whistleblower working inside Krušik.

There is evidence that Belgrade was aware of who was actually behind this hack-and-leak campaign. On November 17, 2019, an anonymous user posted a surveillance video to YouTube with the following description in broken and ungrammatical English: “Russian spies are corrupting Serbia. This is video of the Russian military main intelligence directorate (GRU) officer Colonel Georgy Viktorovich Kleban paying his Serbian agent who is senior Serbian official. Kleban works in Russian Embassy in Belgrade. This is what the Russians do to us, there 'friends.’”

The video struggled to get any attention on YouTube. But the day it was uploaded, an anonymous user emailed Christo Grozev, the head of The Insider’s investigations team, with a link to it and the suggestion that Grozev watch the footage. Grozev was able to confirm Kleban’s identity as a GRU officer and tweeted as much.

Within hours, his tweet was all over the Serbian press. On November 20, the Serbian security service confirmed the footage was authentic and President Aleksandar Vučić’s government summoned the Russian ambassador in order to lodge an official protest. Serbian media then reported that the Russian spy had left the country months before the incident was brought out to daylight. Vučić held a press conference to imply that what Russia had done was not a friendly gesture, without disclosing that the incident had taken place nine months prior.

Undeterred, ArmsWatch continued implicating Serbia in gun-running to enemies of Russia, including to the country Russia was about to try to conquer with more than 150,000 soldiers: Ukraine.

Unit 29155’s intervention against Vučić necessitated the personal intervention of Putin, according to email correspondence between members of the unit. The Russian president scolded both his own GRU hackers and the official Belgrade over the ugly escalation between friends. Unit 29155, from Andrey Averyanov on down to Timur Stigal, was disciplined and instructed not to run uncoordinated operations in the future. Vučić, meanwhile, promptly flew to meet Putin in Russia. The Kremlin put out a reassuring statement, affirming that “the spy scandal” – here it only referred to the one exposed on YouTube, not the scandal its own hackers had participated in – “will not spoil the relations between two brotherly countries.”

Serbian arms have nonetheless continued to pour into Ukraine, often via third-party channels.

On May 29, 2025, the SVR, Russia’s foreign intelligence service, issued a statement titled “Serbia’s Military Industry Attempts to Shoot Russia in the Back.” It read, in part: “Serbian defense enterprises, contrary to the ‘neutrality’ declared by official Belgrade, continue to supply ammunition to Kyiv.” Vučić vowed to form a “working group” to get to the bottom of his country’s ongoing security assistance to his ally’s adversary.

The day after the SVR made this statement, an explosion rocked the Krušik defense plant in Valjevo, Serbia. The factory, the site of several previous explosions beginning from 2022, claimed the detonation was an “accident” that had been caused by “the accidental activation of a detonator booster during the pressing of the explosive substance.” The blast left one worker injured with lacerations and others concussed.

Hatching the eaglets

In mid-2019, Unit 29155 went in search of the next generation of cyber operators. Relying on freelance hackers was getting expensive, and bartering with criminal gangs was more trouble than it was worth – immunity from prosecution could not always be guaranteed as an incentive to hack for the GRU. So Stigal’s team decided to staff up in-house.

They canvassed independent hacking competitions as talent scouts might tour varsity teams in search of star players. Stigal was joined in his recruitment effort by Roman Puntus, who was tasked with overseeing Unit 29155’s hacker department in the late 2010s after its string of tactical victories had gained the favorable attention of higher powers in the Kremlin.

Stigal and Puntus began making trips to the city of Voronezh in southwest Russia. One of these coincided with the first “Capture the Flag” hackathon involving 100 young coders from eight local universities in the city. This two-day competition included an array of tasks that would have distinguished the most talented crop of recruits for the GRU: subjecting them to games of open-source intelligence reconnaissance, cryptography, digital forensics, and the identification of website vulnerabilities.

Based on phone metadata obtained by The Insider, the first group of “eaglets,” as the hackathon organizers fondly referred to the participants, were recruited by Stigal and Puntus in early 2020. The first recruit was the Moldova-born IT student Vitaly Shevchenko, then 22 and a student at the Military Air Force Аcademy in Voronezh.

Capture-The-Flag hackathon. On the right is Nikolay Korchagin, one of Unit 29155's “eaglets”

Vitaly Shevchenko, the first recruited “eaglet”

GRU hacker Vladislav Borovkov

Unit 29155 hackers Dmitry Voronov (left) and Nikolay Korchagin (right)

Unit 29155 hackers Denis Denisenko (center, front row) and Nikolay Korchagin (second right, top row)

Leaked employment data shows that Shevchenko’s starting salary in Unit 29155 was 400,000 rubles per month, or just over $5,100. A high wage for anyone of any age in Russia, it was money well spent by the GRU. Among Shevchenko’s first high-profile penetrations was the Estonian Ministry of Defense and other government institutions in the Baltic nation, a breach that resulted in Unit 29155’s accessing “significant amounts of internal-use information, including commercial secrets,” according to an indictment issued by Estonian prosecutors in 2024 – a rare document in that it correctly attributed this hacking spree to Unit 29155 and to the officers involved.

Shevchenko was also the eaglet with the shortest tenure. He spent just a year on the job and left in late 2021 due to a personal conflict with his superior, Puntus.

Around this period of aggressive expansion, the unit’s founding commander, Gen. Andrey Averyanov, appointed another veteran GRU officer to work with Puntus overseeing Stigal’s creature. Yuri Denisov was the only member in Unit 29155’s hacking department with IT skills. Both he and Puntus answered directly to Averyanov’s deputy, Ivan Kasanyenko.

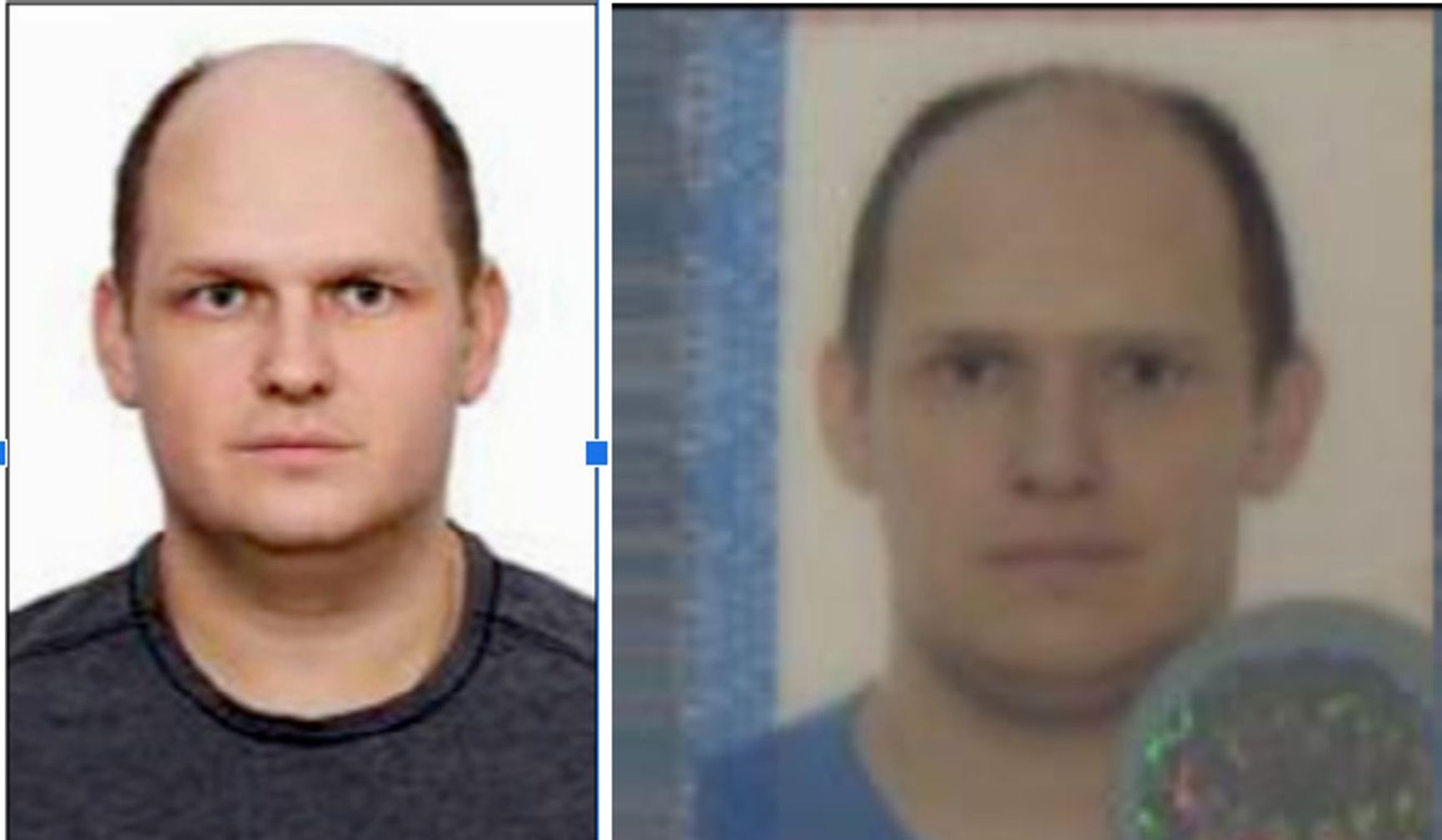

One of the six men included in the superseding indictment of the Unit 29155 hackers and the only non-eaglet of the bunch, Denisov is suspected of spying on Russian dissidents in Europe with the intent to do them harm. He’s traveled under various cover identities: “Yuri Dudin” on trips to Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands, and “Yuri Lukin” on flights to Turkey and Azerbaijan. His phone number was saved in leaked phone contact lists on the social media platform Telegram as “Yuriy C++/Yurily C#” and “Yurily Databases,” indicating his proficiency with coding and computers. Denisov’s wife, in fact, is a professional coder who has worked for some of Russia’s leading cryptography companies.

Passport photos of Yuri Denisov (left) and “Yuri Lukin” (right)

A review of hundreds of Telegram chat groups shows that Denisov is fond of software development and exploiting weaknesses in other people’s computer systems – weaknesses that he himself embodies, as he foolishly used the same phone number for all of his online communications. His Telegram subscriptions read like a day in the life of a GRU hacker. Among the groups he belongs to are “Zero Day/Cyber Security, “Crypto Services,” “Dev Tools,” “Hacker Corner,” “AI tools,” “Stealer Tools” and “RansomWare Developers.” Denisov also subscribes to a group called “DeepNudes,” which is dedicated to creating deep fake pornography.

The Insider retrieved 687 comments left by Denisov on various Telegram forums from early 2020 to April 2025. The comments range from puerile sexual innuendo to racist and reactionary sentiments. For instance, he refers to Ukrainians and Muslim minorities in the Caucasus as “Untermenschen,” the Nazi term for those outside the Aryan race. More than 100 of his messages also attacked the LGBT community.

Denisov is also fixated on the Russian opposition, particularly Alexei Navalny and his Anti-Corruption Foundation.

On December 13, 2020, the GRU spy posted: “It's time for someone to inject the Pfizer vaccine into Navalny, the fatality rate from it is higher than that from the military grade chemical weapon Novichok.” This was two years after Denisov’s colleagues in Unit 29155 slathered Novichok on the door handle of Sergei Skripal’s home in Salisbury, England. (Hours after Denisov posted this message to Telegram, The Insider, Bellingcat, and Der Spiegel would publish their findings identifying the FSB kill squad that poisoned Navalny with Novichok.)

In late 2021, as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine grew near, Denisov intensified his anti-Ukraine chatter, perhaps coincidentally, or perhaps because he was aware of the forthcoming war. In one post on a Ukrainian language channel, Denisov went on a long rant against Volodymyr Zelensky while posing as a native Ukrainian who was opposed to the country’s leadership.

In other settings, Denisov took less care in disguising his online persona.

He identified himself at one point as a Russian colonel with 27 years of military service (which was true); another time he complained that it wasn’t easy being married to a programmer (which his wife was). Both were serious lapses in communications security for which a professional intelligence service would reprimand or sanction an officer.

It isn’t clear if Denisov ran his Telegram presence in a strictly personal or a professional capacity, or if he did so as some creative combination of the two. His first post in early 2020, for instance, appears to be in pursuit of a side hustle to sell database access that he likely had in connection with his work for Unit 29155. (A lot of data brokerage on Telegram and the Russian dark web is managed or maintained by officers of the Russian special services looking to enrich themselves by trading in privileged or sensitive information.)

As Russia's war effort in Ukraine faltered following its February 2022 invasion, Denisov’s comments turned from optimistic to dire, suggesting whatever his original intent in keeping such a hyperactive Telegram persona, he was no longer acting in his capacity as a spy.

Some of his comments verge on treasonous.

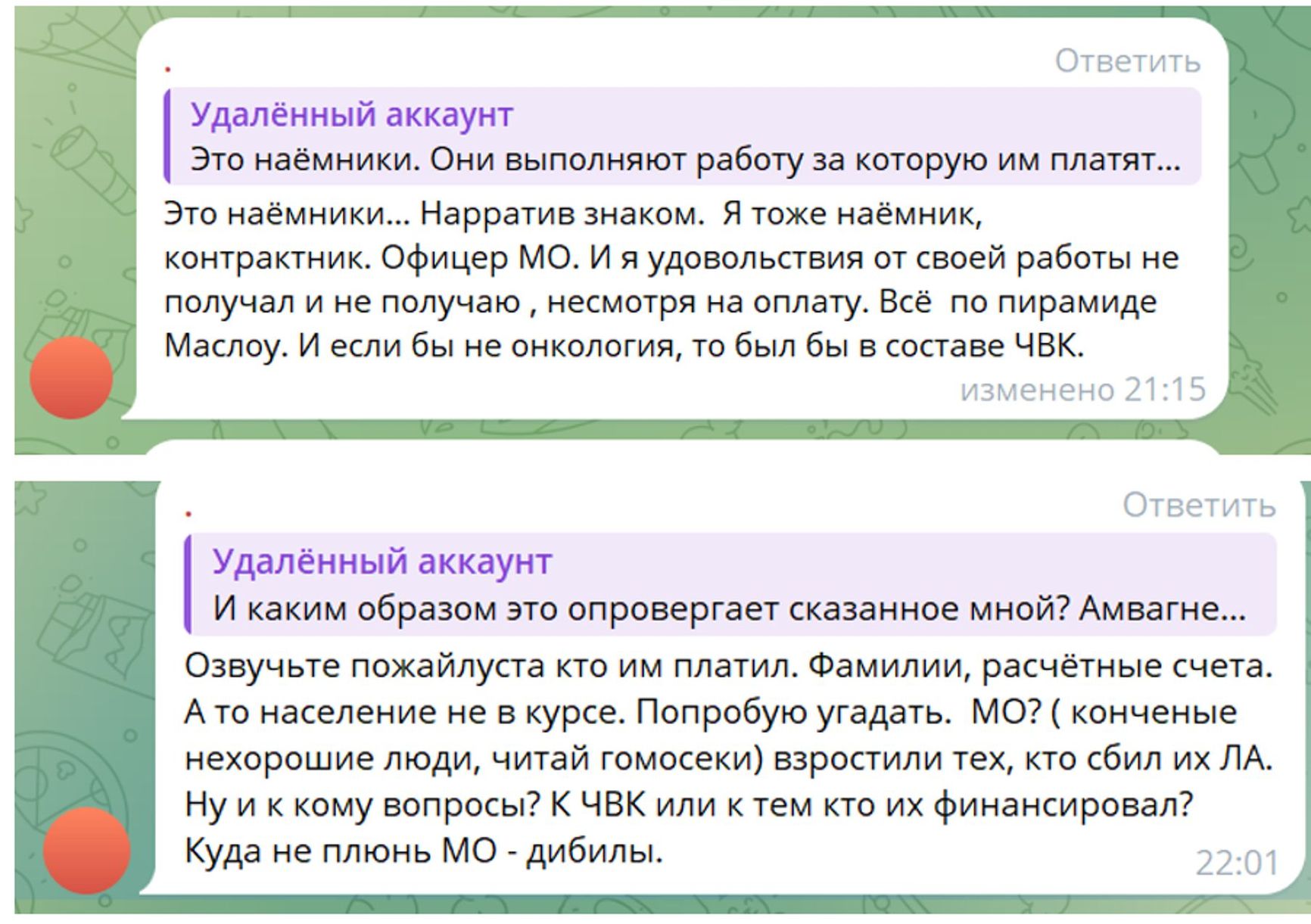

In early 2023, Denisov began praising the efficacy of the Wagner Group, the GRU-aligned mercenary corps founded by oligarch Yevgeny Prigozhin. That in itself might not have been so bad, but Denisov contrasted the combat prowess of Wagner with the decrepitude of the conventional Russian army, routinely assailing the Ministry of Defense, the government bureaucracy to which the GRU answers. Prigozhin and Wagner at this time were condemning the ministry and Russia’s then-Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu, as well as its Chief of the General Staff Gen. Valery Gerasimov, for perceived deficiencies in ammunition for the mercenaries who were dying in droves on the battlefields of Bakhmut and Soledar, in eastern Ukraine.

When Prigozhin and Wagner staged their March on Moscow on June 24, 2023, Denisov wrote the next day: “Is there any bottom that the Ministry of Defense hasn’t broken through?” He also posted on June 25: “I am a contract officer but if I had a chance – had there not been [my] oncological condition – I would have signed up as a mercenary in the PMC.” (The Insider cannot confirm what type of cancer Denisov has or had; only that he underwent frequent MRIs and CAT scans of his head.)

A few days after Prigozhin’s power grab was quashed, Denisov posted: “Everyone at the [Ministry of Defense] are total scum, in other words – faggots.”

Under Russian law, it is a crime punishable by up to five years in prison to “discredit the armed forces.”

In addition to leaving a near-complete digital fingerprint of his activities and thoughts through his promiscuous and unprotected Telegram chats, Denisov committed other blunders.

The Insider discovered his four different cover identities only because he used the same burner phone for booking flights under all four of his fake names, and to pay for parking for a car registered under his real identity. He also used that phone to book travel for his subordinates in the hacking department, including Tim Stigal.

Denisov used the same burner phone for booking flights under all four of his fake names and to pay for parking for a car registered under his real identity

Working backward from a single telephone number, The Insider was thus able to anatomize the entire cadre of cyber operatives working for Unit 29155.

Preparing for war

The Fifth Service of Russia’s domestic security agency, or FSB, is widely understood to have been the main Russian intelligence organ tasked with destabilizing Ukraine in advance of the February 2022 invasion. And indeed, on December 1, 2021, and January 25, 2022, there were reports that coup attempts — likely backed by Moscow — were in the works. Now, new evidence shows that GRU Unit 29155 was involved in similar efforts, pioneering tactics in Ukraine it is now employing on a much broader scale in its escalating “shadow war” against the West.

In August 2021, five months before Russia’s full-scale invasion, Unit 29155’s hackers attempted to exacerbate a rift between Ukraine’s nationalist groups and the Zelensky administration. Soldiers from many of Kyiv’s most effective units, which had been fighting off Russian forces in the Donbas since 2014, were less than enthusiastic about their president. In 2019, a visit by Zelensky to the front lines resulted in an on-camera argument between the head of state and members of the Azov Battalion. In 2021, Zelensky was still politically vulnerable to protest and pressure from nationalist elements in Ukraine, including those opposed to his campaign pledge to end the war in the east by making concessions to the Kremlin.

Adhering to the familiar formula of false-flag operations, Stigal recruited dozens of low-level assets to impersonate members of the Azov Battalion – one of Ukraine’s best paramilitary outfits, but also a group that had faced scrutiny in the West over the right-wing tendencies of some of its members. He went further and engaged with at least two top commanders in Azov, impersonating a leader of the Chechen dissident Ichkeria organization, which is opposed to Chechnya’s warlord-president Ramzan Kadyrov, and offering them an alliance against Zelensky. Duped by Stigal, at least one of the Azov commanders accepted the offer of help.

Stigal recruited dozens of low-level assets to impersonate members of the Azov Battalion – one of Ukraine’s best paramilitary outfits

Azov underwent significant reforms before the war, becoming first a regiment and then a brigade. Its fighters were responsible for holding out in the Azovstal metallurgical facility in Mariupol in the Spring of 2022 – against overwhelming Russian forces – and are now seen as national heroes, with its special forces forming the backbone of the Third Assault Brigade, one of the Ukrainian army’s elite units. But before the full-scale invasion, Unit 29155 sought to exploit Azov’s potential as a spoiler of national unity by portraying it as being vehemently against Ukraine’s elected leadership.

The activities run by Unit 29155 in Ukraine are outlined in a folder The Insider found on a now-disused computer server. The subheadings read like a how-to guide on acts of sabotage and social subversion: “Bacteriologists/Laboratories,” “Graffiti in Cities,”

“Work with Nazis,” and “Targets Among Ukraine’s Authorities.”

The first folder contained dossiers on six Ukrainian military scientists who were working on bacteriological research. Although Unit 29155 doesn’t explain its interest in this field or in these personnel, it is likely that this data was to be used in furthering the “biolabs in Ukraine” conspiracy theories. After years spent on the fringes of the global information space, Gaytandzhieva’s accusations found a wider-than-usual audience after the start of Russia’s full-scale war. As late as March 2024, Donald Trump’s future Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard was repeating elements of the “biolabs” story in an interview with Tucker Carlson.

Remotely-recruited assets in Ukraine were paid the equivalent of between $1 and $5 for spraying graffiti expressing antipathy towards Ukraine’s president

The folder titled “Graffiti in Cities” included reports on thousands of acts of vandalism meant to highlight antipathy towards Ukraine’s president, including by repurposing language used in 2014 to denounce Vladimir Putin. As a result, “Zelehuylo” – “Zelensky is a dick” – and other variations thereof were daubed on buildings in multiple Ukrainian cities throughout the summer of 2021. This folder kept geolocated “proof of delivery” photographs and chats with remotely-recruited assets in Ukraine who were paid the equivalent of between $1 and $5 for the graffiti, depending on the importance and risk involved in marking a certain location. The assets were also required to report their walking routes and “number of steps walked” per day.

Samples of "Zelensky is a dick" graffiti commisioned by the GRU in Ukraine

Unit 29155’s reports also have crypto payment wallets. The Insider retraced the main ones that were used to compensate the graffiti artists; they show payments of hundreds of thousands of dollars spent around the time of the campaign.

The “Work with Nazis” folder had only one screenshot, which shows an alleged chat with a senior member of Azov in Chernihiv. The chat appears to outline the coordination of a campaign to print t-shirts bearing the same anti-Zelensky messaging seen in the grafitti. The Insider has chosen to redact the name of the Azov memberc– who is currently serving in the Ukrainian Armed Forces – owing to the fact that he was unaware he was engaging with members of the Russian intelligence services.

The last folder, “Targets in Government,” kept reporting on surveillance and sabotage work focusing on three members of Zelensky’s administration in charge of European integration: Andrii Boyko, [first name unknown] Zhurakovsky, and Ihor Zhovka. Unit 29155 evidently had troubles identifying the personal details and home addresses of Boyko, who had “more than 60” namesakes in Kyiv, and Zhurakovsky, who at one point “had owned a Skoda Aktavia.” However, the group succeeded in locating Zhovka — Ihor Ivanovych, the deputy chief of Zelensky’s Presidential Office.

A separate document, titled “expenses for processing Zhovkva,” shows a total amount of $7,000 plus bonus, with a downpayment of $400 – presumably for locating the official’s address. The folder was full of dozens of photographs of Zhovkva and his residence, detailed information about him and his family members, and call records of his phone number, including the geolocations of its use for a six-month period ending September 13, 2021.

Early on the morning of October 22, 2021, a Molotov cocktail was thrown into Igor Zhovkva’s home in Kyiv. An unnamed 20-year-old Ukrainian was arrested, telling authorities he was promised $7,000 to incinerate the home of the Ukrainian official. He said he was tasked by an anonymous person via an encrypted messenger. (Yuriy Denisov, the overseer of Unit 29155’s hackers, left a comment in a chat group that had published a link to the new story about the attack on Zhovkva’s home. Denisov’s comment was “idiots.”)

Unit 29155 is currently using the methods drawn up by Stigal’s hackers for destabilizing Ukraine in pursuit of its sprawling campaign of sabotage and arson attacks against the West. GRU operatives remotely locate and use Telegram to recruit saboteurs from countries including the United Kingdom, Poland, the Baltics, and Germany, offering them cryptocurrency for setting fire to strategic sites such as military installations or defense plants, or to softer targets like warehouses, shopping malls, or bus depots. More ambitious plots, which have so far been thwarted by Western counterintelligence and law enforcement, include smuggling incendiary devices encased in sex toys and cosmetics aboard DHL cargo planes bound for North America.

GRU operatives remotely locate and use Telegram to recruit saboteurs from European countries, offering them cryptocurrency for setting fire to strategic sites

In addition to the offline hybrid activities of Unit 29155, during the same period Stigal’s team resorted to hacking and online deception and influence campaigns. Screenshots found on the same abandoned server show that Unit 29155 registered a group of domain names that were used for spear-phishing, credentials-harvesting, and disinformation during the months prior to the invasion. It created spoofed websites for Zelensky’s office and for several Ukrainian ministries. Some of these activities were reported by cybersecurity experts, but this is their first attribution to Unit 29155.

Double life, second family

Data suggests that Tim Stigal was removed or resigned from the hybrid department of Unit 29155 shortly before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Medical records show he suffered from a variety of health issues and spent more than a month in critical condition in a hospital in 2020 due to complications from Covid. Following Stigal’s departure, most of his responsibilities were reassigned to his boss, Roman Puntus.

Following Stigal’s departure, most of his responsibilities were reassigned to his boss, Roman Puntus, who appeared more interested in his personal pursuits than in winning the war

Puntus assumed this managerial and HR role of Unit 29155’s hackers at precisely the moment when the Kremlin was preparing for its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and cyberattacks were expected to play an important role in the operation. But Puntus had little understanding of IT and relied heavily on his subordinates. He also appeared more interested in his personal pursuits than in winning the war.

The only publicly available image of Roman Puntus. The identity of the woman in the back is unknown.

In Stigal’s absence, the role of liaison between Unit 29155 and the FSB was taken up by a hacker seconded to the latter service, Evgeny Bashev. Bashev had been involved in state-sanctioned cyber operations for years, using his Rostov-based private company, Impulse, to mask the Kremlin’s role in his operations. The server he used was called Aegaeon, and the DNS and IP addresses were provided by his Rostov-based company named Impulse.

Puntus adopted Bashev's model, but decided to add yet another in-between layer, ostensibly for further deniability. To do that, he incorporated a shell company unimaginatively and confusingly christened Aegaeon-Impulse, which was registered to an accountant, Darya Kulishova. Although Kulishova was a front, she was not selected at random. She was Puntus’s mistress.

The married GRU boss’s affair with Kulishova was not his first extramarital escapade by far. In fact, Roman Puntus’s work phone number – registered in the cover identity of “Roman Panov” – is listed as a regular contact with more than seven VIP escorts in Moscow, as can be seen from Russian phone-sharing apps. (One of the descriptions of Puntus in one prostitute’s phone book is “Military – but generous, drives you home in his Chevrolet.”)

Puntus’s relationship with Daria Kulishova was no mere fling.

Flight and train booking records show that he regularly used his cover identity to travel from his home with his wife and children in Moscow to visit Kulishova in hers, in Rostov, and the two took regular trips to the subtropical Russian city of Sochi, ordering lavish meals and champagne to their luxury hotel rooms.

On November 15, 2023, nine months after one of their assignations in Sochi, Kulishova gave birth to a son, whom she named Matvey Romanovich, adopting the patronymic of the man who sired him. Ten days earlier, Puntus arrived in Rostov to anticipate the birth of his love child. On her official application for state benefits, Kulishova wrote: “I am not married to the child's father and he does not support the child.”

The photoshoot of Puntus's mistress Darya Kulishova dated early February 2023. She would give birth to a son nine months later

That was only partly true.

While unwilling or unable to provide alimony himself, Puntus was able to use his position as the head of Unit 29155’s cyber department to give his second family their own corporate entity, Aegaeon-Impulse, which received GRU funds earmarked for setting up the digital infrastructure necessary to engage in more hacking.

Puntus's second family controls Aegaeon-Impulse, which received GRU funds earmarked for setting up the digital infrastructure necessary to engage in more hacking and manufactured military drones

Puntus also brought his paramour into his service. Kulishova wasn’t just an idle nominee director of Impulse, and the company wasn’t just an empty shell. It manufactured military drones, which have proliferated to such an extent on both sides in Russia's war in Ukraine that they’re now credited with keeping either side from breaking through along the 1,000-mile frontline.

In October 2023, Kulishova emailed herself a PowerPoint outlining technical characteristics of three new First Person View (FPV) drones with the “capability to self-direct and enter closed areas.” The author of the PowerPoint was Evgeny Bashev, and one of the emails was titled “corrected presentation,” indicating that Kulishova may have edited or contributed to the slideshow, which closed with the standard Russian military phrase, “The report has been concluded.”

Kulishova also registered a trademark for Aegaeon-Impulse under the name “Sabrage Sabotage,” a possible double reference to both the many bottles of champagne she and Puntus enjoyed over those steamy nights in Sochi and to the painstaking work her new employer had long been engaged in overseas.

Meanwhile, the Aegaeon targeting server Bashev established in Rostov was left dormant, insecure, and unprotected. Earlier this year, hacktivists discovered it and retraced Unit 29155’s activities dating back to 2021. This material was then leaked to The Insider.

In keeping with the institutional culture of Unit 29155, Puntus’ private indiscretions gave way to professional misconduct. They may have also distracted him from doing his job properly.

In Greek mythology, Aegaeon is a hundred-handed monster who breathes fire from his fifty heads and fights alongside Zeus in the war against the Titans. He then betrays the king of the gods and is tortured ceaselessly by the Furies for his treachery.

The target list

According to the Aegaeon logs, in late 2021 the Unit 29155 hackers began targeting a range of Ukrainian government websites. In January 2022, they expanded their list to include energy providers and anti-corruption organizations. But these pre-invasion efforts were far less effective than past Russian cyber operations against Ukraine.

From 2015 to 2017, GRU Unit 74455 successfully used malware to disable Ukrainian power plants, at one point blacking out all of Kyiv.

Puntus and his protégés never pulled off anything quite so spectacular. But from January 13-14, 2022, weeks before Russia’s invasion, they did breach the websites of several Ukrainian companies and government departments, posting a message on the main pages stating that they had managed to destroy all of the relevant organizations’ data. According to the Ukrainian authorities, the hackers were bluffing – they hadn’t caused significant damage, let alone carried out the mass erasure of digital data.

Around the same time, Unit 29155 broadened the net well beyond Ukraine, going after Western academic and research-oriented targets such as the University of Colorado’s website, a Polish web design studio specializing in computer games, a solar panel company, a medical clinic in Azerbaijan, and the Tashkent Medical Academy.

From January 2022, Unit 29155 broadened the net well beyond Ukraine, going after Western academic and research-oriented targets

The hackers searched for vulnerabilities in government agencies and critical infrastructure sites in Uzbekistan, Georgia, Czechia, Slovakia, Estonia, Poland, Moldova, and Armenia, the Aegaeon logs show. Of the hundred or so known targets of Unit 29155, a third were in Czechia, where operatives from the same GRU unit blew up two Ministry of Defense-owned ammunition warehouses in Moravia in 2014.

The majority of requests from the servers are from 2021 and 2022, after which the hacking either significantly decreased or Unit 29155 simply discarded the Aegaeon server in favor of others.

Among the phones that the hackers checked for call records and metadata were not only the objects of their professional interest, but those of acquaintances and relatives. One target was Zhana Barskaya, the mistress of Unit 29155 commander Andrey Averyanov.

Judging by the phone numbers they were interested in, it is clear that the hackers were also avid readers of this publication.

When The Insider published a story in January of this year about Unit 29155 suborning Afghan couriers to pay Taliban militants to attack U.S. and coalition forces in Afghanistan, the hackers scanned the number of Ivan Senin, one of the directors of the bounty program, within 24 hours of the article’s release.

With additional reporting by Michael Wasiura