Ilya Repin. October 17, 1905

Ilya Repin. October 17, 1905

In Russia, pro-war bloggers are grumbling (albeit cautiously), and society at large is showing increasing signs of war fatigue. While few are predicting an imminent end to Putin’s war in Ukraine, Russian history demonstrates that failed military campaigns can cause even the most devoted supporters of the country’s leadership to lose their loyalty — most notably in 1905, when Russia’s defeat in the Russo-Japanese War turned staunch supporters of the autocracy away from the tsarist government. What was initially expected to be a swift and victorious war turned into a profound shock to the foundations of the empire, marking the beginning of the end for the centuries-old monarchy.

Laurels on chains

Monarchists go republican

The army’s decay

Restoring order

By the late 19th century, Russian society had reached a kind of consensus, one in which people of the most divergent political views — from Prince Pyotr Vyazemsky and Marquis Astolphe de Custine to Sergei Witte and Vladimir Lenin — expressed largely the same idea: that political freedom was a fair price to pay for military might and imperial glory. As poet Valery Bryusov put it succinctly: “Yes! Chains can be beautiful, / When they are wreathed with laurels.”

“Our society has a very characteristic trait: it has been politically educated to focus on external rather than internal affairs,” Alexei Suvorin, the publisher of leading newspaper Novoye Vremya, wrote in 1893. “Internal matters were guarded with Othello’s jealousy by the bureaucracy as its exclusive domain... Foreign policy was something entirely different. It had always been a public matter. And the patriotism that existed and grew within society was based on military actions and victories.”

By early 1905, however, it had become clear that the monarch was astonishingly inept in the very sphere that the autocratic regime exploited as a counterweight to all of its internal shortcomings. The war with Japan dragged on as an unbroken string of defeats, each more humiliating than the last. Now it was no longer only the hardened opposition but also ardent statists like Bryusov himself who realized that the tsarist regime was a paper tiger. The laurels had fallen off, and the chains suddenly began to cut the eye with unbearable sharpness.

The monarch had proved astonishingly inept in the very sphere that the autocratic regime exploited as a counterweight for all of its domestic shortcomings

True, Russia had lost a war half a century earlier — the Crimean War. But at least then it had fought against two of the world’s great powers. This time, however, the humiliating blows were dealt by those whom Russians had until recently referred to with disdain as “Jappies” (“япоши” in Russian).

It was during the Russo-Japanese War that the police first began recording a previously unheard-of phenomenon: widespread instances of peasants cursing the emperor and his family. If the authority of the state had sunk so low even in the eyes of its most downtrodden and voiceless, what did that portend among those who considered themselves “society”?

“The war exposed many of our internal sores and provided abundant fuel for criticism of the existing state system,” wrote Deputy Interior Minister Vladimir Gurko in his memoirs. “It drove into the revolutionary camp many of those concerned with the fate of the homeland, and thus not only gave a powerful impulse to the revolutionary movement, but also endowed it with a national and noble character.”

Gurko’s observation is echoed by gendarmerie general Globachev, who wrote that the events of the 1905 Revolution “were founded, if you will, on a national idea. The monarchy had disgraced the prestige of the Great Russian Power, and a new authority — a people’s power capable of restoring Russia’s former greatness — had to rise in defense of national interests.”

Even Lev Tikhomirov, a former Narodnaya Volya revolutionary whose path to embracing monarchism was long and painful, wrote in his diary in March 1905: “Here is what an absolutist monarchy does! Just ten years [of Nicholas II’s reign] are enough to destroy the man and ruin the country.” By August, he expressed himself even more sharply: “The government is so vile, so brazen, that nothing could be worse, even if a republic were declared… If the Russian people wish, they can restore the monarchy, but for now it has ceased to exist.”

“The merits of autocracy are as clear to me as they are to you, but it has outlived itself,” the newspaper publisher Suvorin wrote in reply to the criticism voiced by monarchist Sergei Tatishchev, biographer of Alexander II.

“The future, of course, belongs to the revolution,” wrote Petr Pertsov, a former conservative who just a year earlier had been promoting “mighty Russian imperialism.” Now, wrote Pertsov, “One cannot fail to see where the truth lies. I myself am now a ‘leftist’!”

In the spring of 1905, a liberal aristocratic opposition began to take shape in Russia, organizing local congresses and advocating for the convocation of an all-Russian parliament. Everyone’s hopes were pinned on public oversight — particularly when it came to the naval and military departments, whose corruption was the stuff of legend.

But the liberals were the least pressing of the regime’s problems: a split had also emerged within the bureaucratic elite. Alexei Arbuzov, head of the Department of General Affairs at the Ministry of Internal Affairs, responded to a colleague’s remark about the need for a restoration of order: “For 23 years this strong authority has been in effect, and look what has come of it — the disorder we are now experiencing.”

The Minister of Internal Affairs himself, Prince Svyatopolk-Mirsky, wrote to a relative: “Am I to blame that Russia has turned into a powder keg? I recognize the need for reforms, so that we will not soon be forced to grant the constitution that will be demanded. I assure you, we are not far from that point if we maintain the current system of governance, which has brought Russia to a volcanic state.”

Such pillars of officialdom as State Council Chairman Dmitri Solsky and Minister of Agriculture and Domains Alexei Yermolov implored the tsar to convene a Zemsky Sobor (a form of parliament) and “establish direct contact with the people,” as the monarchy’s traditional support from the nobility was crumbling before their eyes.

“Am I to blame that Russia has turned into a powder keg?”

Even the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna demanded that her son Nicholas II make concessions to the “well-meaning part of society,” threatening to return to Denmark unless they were granted: “Let them twist your head off without me!” According to apocryphal accounts, Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich, the General Inspector of the Cavalry, also threatened to shoot himself in Nicholas II’s presence if a constitution was not proclaimed in one form or another.

But perhaps none surpassed Foreign Ministry chancery secretary Konstantin Nabokov (uncle of the writer Vladimir Nabokov), who in a private letter asked when “a bold terrorist act would put an end to the vile mockery of the Holstein-Gottorp bastard over his loyal subjects?”

Yes, there were still some hardliners in the emperor’s circle. These included Saint Petersburg Governor-General Dmitri Trepov, known for his famous phrase “spare no cartridges.” But the question was whether they would have enough cartridges — and enough loyal soldiers to fire them — when almost the entire country had turned against the regime.

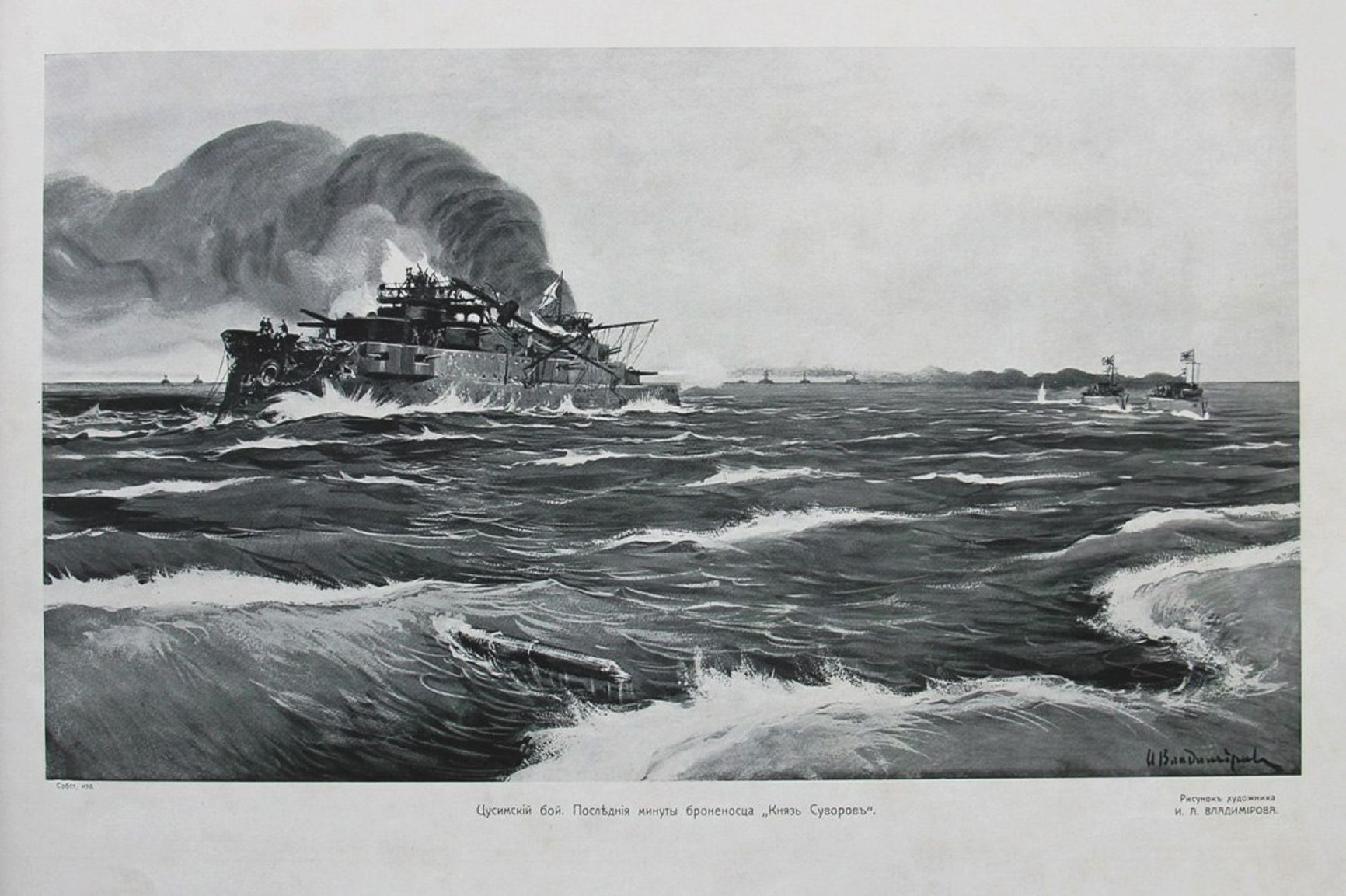

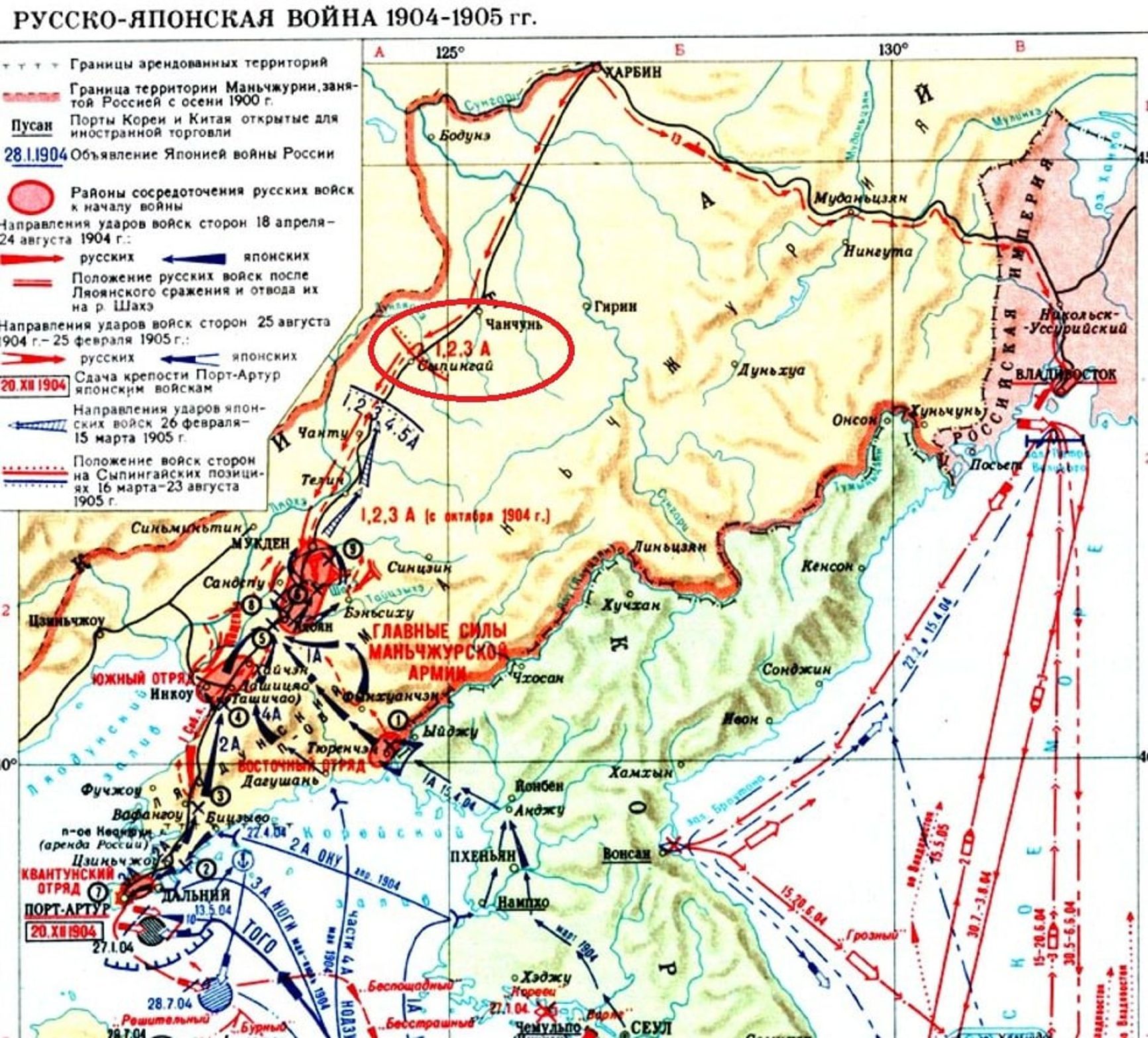

Tsar Nicholas II could only hope for a miracle to change the course of the war against Japan — and, with it, public sentiment in Russia. That miracle was expected to come from Admiral Rozhestvensky’s 2nd Pacific Squadron, sailing from the Baltic Sea to Vladivostok in the Russian Far East. Historians later debated at length whether it might have been wiser to halt the fleet in Saigon, using it as a “fleet in being” during the inevitable upcoming negotiations with Tokyo. But war is the continuation of politics, and politics compelled the inflexible autocrat to lay his last card on the table.

He played his card — and lost. “There is no one who would argue that the consequence of this battle will be other than a constitution,” Alexandra Bogdanovich, the hostess of a fashionable Petersburg salon, wrote in her diary four days after Russia lost the Battle of Tsushima.

The tsar himself was forced to acknowledge this new reality. On June 6, he received a joint delegation from the local representative bodies, assuring the public representatives for the first time of his intention to convene “elected representatives of the people” immediately after the war’s end.

The emperor ratified the peace treaty with Japan, and two weeks later came the famous October 17 Manifesto — Russia’s first constitution of sorts, which proclaimed freedom of conscience, assembly, and association, and called for the convocation of the State Duma.

Summoning a parliament amid rising revolutionary unrest was a perilous move for an authoritarian ruler. Many warned Nicholas II that he was following in the footsteps of Louis XVI. The situation was aggravated by a complete disintegration of the regime’s main pillar: the Russian imperial army. Decay affected not only the rear garrisons but also the front-line units left on the Siping positions in Manchuria after the peace treaty.

Summoning a parliament amid rising revolutionary unrest was a perilous move for an authoritarian ruler

Even before the October 17 Manifesto, unrest and strikes had broken out along the entire Trans-Siberian Railway, including among railway workers and telegraph operators. As a result, Russia’s Manchurian army found itself cut off from the country and in informational isolation starting from Oct. 28. The army included 400,000 reservist peasants who, in the words of General Alekseev, had become “hysterical women, flabby, weak-willed, obsessed with a single thought: to go home.” They comprised an enormous, highly combustible mass.

Talk among the troops was rife with the most fantastic rumors: about an uprising in Finland, an English landing in Kronstadt, tens of thousands killed in street fighting in Petersburg — and above all, about the beginning of a redistribution of landlord estates. “Discipline, already fallen, sinks even lower, and the undeveloped masses see freedom in the fact that now every soldier is ‘on equal footing with an officer,’” noted General Alekseev. Conditions in the army were so dire that some units were forcibly disarmed, and a composite regiment of the most reliable officers and soldiers was formed to guard the Supreme Commander’s headquarters.

Conditions in the army’s rear were even worse: “The October 17 Manifesto reached us only several days after its issuance,” recalled General Budberg, who headed the Vladivostok Fortress staff. “Special agitators quickly explained to the lower ranks the meaning of the new ‘freedoms,’ and, in essence, from that moment our troops ceased to exist as an army. Their leaders — or, more accurately, their ringleaders — promised immediate return home, exemption from all duties, inspections, and labor, distribution of all military pay, and full ownership of all ordinary and warm kit. The officer corps was thrown into confusion, partly intimidated, and, aside from administrative and provisioning orders, almost completely stopped performing their command functions.”

When drunken soldiers staged a riot in Vladivostok, “many officers abandoned their units and hid, disguising themselves in civilian clothes; others — especially naval officers — sought refuge on foreign commercial steamships.”

With few exceptions, the same picture was observed across the empire, including in Moscow, where by December 1905 strikes had escalated into an open armed uprising. “Its strength, of course, lay in the unreliability of the troops — all the garrison infantry had to be kept in the barracks,” eyewitness Sergei Melgunov recalled.

“Upon arriving in Moscow, I immediately noticed one characteristic feature: military officers were scarce everywhere,” wrote General Rerberg in his memoirs. “While sitting at the barber, wrapped in a white sheet, I observed poorly dressed men entering the shop from the hall, greeting the barber as they went, and exiting through another door. From that same door came officers of the Moscow garrison, wearing sabers and revolver holsters. I asked the barber to explain this discrepancy. From his words, I learned that it was unsafe for an army officer to appear on the streets of Moscow, as there had already been several murders of officers in broad daylight. Therefore, almost all officers of the Moscow garrison had acquired inexpensive civilian coats and hats and wore them over their uniforms when going into the city. In the barber shop, they changed into military dress before taking up their duty.”

All these scenes are so reminiscent of February 1917 that the question invites itself: why did Russia’s monarchy not crumble 12 years earlier? Or, conversely, why did it survive 1905 only to collapse later? There were several reasons, and it makes sense to start with “exceptions to the rule,” such as the Semyonovsky Regiment officers.

Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich, Nicholas II’s uncle and the commander of the Guard Corps, played an important role. According to his contemporaries, he may not have been particularly brilliant, but he possessed a keen political instinct. At the very start of the war with Japan, he categorically refused to send a single Guards unit to the front, forbidding even the transfer of individual officers to the active army. He sensed that the most elite — most loyal — Guards personnel would soon be needed to defend the throne in Russia itself, not to fight in Manchuria.

The best Guards regiments — Semyonovsky, Preobrazhensky, and Lithuanian — remained an unshakable bastion of order. On Dec. 25, 1905, the Semyonovsky Regiment was sent to Moscow with orders to “not cease fire until serious losses are inflicted, and to do so in a manner that will discourage any attempt to start it again.”

By Jan. 1, 1906, the uprising in the million-strong city had been suppressed by a single regiment that inflicted relatively moderate casualties: 62 killed and wounded. Moreover, the decisive use of force quickly shifted public sentiment in Moscow, and when the regiment marched to Nikolayevsky Station two weeks later to return to the capital, huge crowds greeted them joyfully.

Next, an operation to unblock the striking Trans-Siberian Railway proceeded just as smoothly. On Jan. 4, 1906, a detachment under General Meller-Zakomelsky set out from Moscow for Siberia, and by early February, the generals had restored relative order on the line, returning striking garrisons to their barracks, confiscating stolen weapons, dispersing local soviets, and putting the strikers back to work.

“The main credit for this operation belongs personally to Meller-Zakomelsky,” recalled War Minister General Rediger. “Only with his executioner-like character was it possible to hit and whip so consistently along the entire railway, instilling a salutary terror in all rebellious and striking elements.”

Rediger’s choice of the word “rebellious” was particularly apt. In 1905, the revolutionary tide suffered from a catastrophic lack of organization, as the October 17 Manifesto signed by Nicholas II eliminated a split in the elites that threatened to transform the riot into a full-blown revolution.

The “well-meaning part of society” proved entirely satisfied, and the rebels were led, as the Guards officers put it, by “all sorts of scum” who possessed no legitimacy even in the eyes of the insurgents themselves. Deep down, in the words of the writer Saltykov-Shchedrin, “the villains knew they were rebelling,” and therefore quickly gave in under the pressure of decisive troops, once such forces presented themselves.

By signing the October 17 Manifesto, Nicholas II eliminated a split in the elites that threatened to transform the riot into a full-blown revolution

Moreover, at that moment, the interests of the authorities and the combustible mass of soldiers coincided: the sooner order was restored, the greater the chances of getting home quickly.

In 1917, the situation was far worse. The war had once again split the elites, but this time the tsar made no concessions to society. Nicholas II’s stubbornness — he was clearly unfit for supreme command yet refused to yield an inch of power — gradually began to irritate even the highest-ranking generals.

Against this backdrop, food riots erupted in Petrograd (St. Petersburg, renamed in 1914 on the wave of anti-German sentiments), quickly escalating into a soldiers’ mutiny with an anti-war undertone. Two factors — the split among the elites and the armed uprising — coincided in 1917 not only in time but also in geography: in the empire’s capital itself. The mutinous regiments immediately gained a legitimate “patron” in the form of the State Duma, turning the mutiny into a revolution and quickly swaying the general staff to their side.

Meanwhile, Nicholas II remained confident that a small number of reliable regiments would suffice to restore order, just as they did in 1905. Accordingly, General Ivanov was sent to Petrograd with several units, including two battalions of St. George’s Cross holders from the Supreme Command’s guard detachment.

Nicholas II failed to take into account that Ivanov was no Meller-Zakomelsky and that the Guards of 1905 were long gone. That guard perished during the autumn campaign of 1914, and the Guards regiments painstakingly rebuilt afterward fell again during the Stokhid operation at the end of Brusilov’s breakthrough. The old Semyonovsky officers were also gone: on the way to the capital, the commander of one of the St. George battalions, General Pozharsky, told his subordinates that he would not allow them to fire on the crowd, even under the emperor’s orders. What an ironic twist of fate: in 1613, one Pozharsky placed the Romanovs on the throne; in 1917, another Pozharsky removed them.

When it became clear that even His Imperial Majesty’s Own Convoy was unwilling to repeat the feat of Louis XVI’s Swiss Guard, who perished defending their sovereign, Nicholas II recorded in his diary: “Treachery, cowardice, and deceit everywhere.”

In fact, the tsar had deceived himself, placing too much faith in the universal power of the bayonet and forgetting the maxim of one of his fellow sovereigns: much can be accomplished with bayonets, but one cannot sit on them forever.

К сожалению, браузер, которым вы пользуйтесь, устарел и не позволяет корректно отображать сайт. Пожалуйста, установите любой из современных браузеров, например:

Google Chrome Firefox Safari