Vladimir Putin has placed the Russian assets of Danone and Carlsberg under the “temporary management of the Russian Federation.” This move establishes a precedent that raises concerns about potential future expropriations and evokes inevitable comparisons with events from a century ago: much like the Bolsheviks, who initially took custody of ownerless enterprises left behind by their proprietors, eventually progressed by 1918 to a broader nationalization of entire industries.

Content

Step by step: stages of nationalization

The process of nationalization

The Likino Manufactory, the first nationalized enterprise

The Abrikosov and Sons Partnership

The Factory of the Russian Joint-Stock Company L.M. Ericsson and Co

The Shustov and Sons Partnership

The Muir and Mirrielees Furniture Factory

Singer Manufacturing Company Plant

Step by step: stages of nationalization

There is a stereotype that the Bolsheviks nationalized all private property as soon as they came to power. In reality, the process of nationalization occurred in several stages, with different industries being nationalized at different times.

The initial stage involved the nationalization of land: The Bolsheviks promptly issued the Decree on Land on October 26, 1917 (November 8, 1917 in the new calendar), the very next day after their rise to power. According to this decree, the estates of landowners, including “all their living and non-living assets, estate structures, and belongings,” were expropriated without any form of compensation. This approach was also extended to encompass lands owned by religious institutions and monasteries. However, it's worth noting that the Decree did not immediately apply to the lands of “ordinary peasants and Cossacks” (although this was short-lived, as the Land Code adopted in 1922 ultimately abolished private land ownership rights). Subsequent stages followed: banks were nationalized on December 14 (27), 1917, followed by the nationalization of the trading fleet on January 23/February 5, 1918. The oil industry came under state control on June 20 of the same year. It was only towards the end of June 1918 that the Bolsheviks extended their reach to other branches of industry, leading to the comprehensive nationalization of entire sectors. Concurrently, during the summer of 1918, private property rights to urban real estate were also rescinded.

The Decree on Land

The nationalization of enterprises was preceded by a preparatory stage. Several months earlier, on November 14 (27), 1917, the Bolsheviks enacted the Regulation on Workers' Control (although in practice, worker control had been established on many enterprises long before the Bolsheviks came to power, after the February Revolution). This meant that while formally the enterprises remained under the ownership of their previous owners, management now involved workers through factory and plant committees. According to the regulation, these committees oversaw both the production and financial operations of the enterprises, gaining access to financial records and storage facilities, influencing recruitment and termination decisions. Owners were prohibited from obstructing or concealing information. The intention was for this measure to empower workers to fully grasp the intricacies of production, so that they could eventually assume control.

In reality, the factory committees had limited decision-making power. They were subordinate to higher authorities: Councils of Workers' Control under city councils, the All-Russian Council of Workers' Control, and, on a larger scale, the Supreme Council of the National Economy (VSNKh). In any case, owners and former managers of enterprises were increasingly marginalized from leadership roles. However, it was not yet possible to do without them completely: even Lenin acknowledged that “without the guidance of specialists from various fields of knowledge, technology, and experience,” it would be impossible, as the new owners lacked sufficient knowledge and experience in production organization.

Myasnitskaya Street in Moscow. The Building of the Scientific and Technical Department of VSNKh

During this preparatory phase, the nationalization of enterprises was also undertaken, but it still followed a specific pattern: a unique decree was issued for each enterprise, marking its transfer into state ownership. During this period, nationalization was selectively applied to either abandoned enterprises or as a punitive response to owners who resisted the decisions of workers' control. These early nationalization decrees interestingly cited formal justifications, such as an owner's disappearance in an “unknown direction,” the shutdown of a business by its owner, notifications of liquidation, defiance of workers' control authorities, cessation of funding, and more. Such rationales were needed to legitimize these actions by the emerging authorities.

Starting from the summer of 1918, nationalization took on a systemic approach, encompassing entire industries rather than isolated businesses. By the fall of 1918, over 9,500 enterprises had undergone nationalization, and by the first half of 1919, the major industrial sectors were nearly entirely under state control. The subsequent phase extended to medium-sized and smaller enterprises, marked by a proclamation on November 29, 1920, which mandated the nationalization of all industrial enterprises “employing over 5 workers with a mechanical engine or 10 workers without a mechanical engine.”

The process of nationalization

The process of nationalization was far from uniform. Within the ranks of the Bolsheviks, there existed no unanimous consensus when it came to the concept of comprehensive nationalization. While everyone acknowledged the ultimate necessity of this step, there were varying opinions on the speed and timing: many voiced apprehensions that a rushed nationalization could potentially inflict substantial harm upon production.

Even Lenin, who initially embraced radical viewpoints, began to cautiously express reservations about an excessively swift nationalization as early as 1918:

“I conveyed to every workers' delegation I engaged with: Do you desire the nationalization of your factory? Very well, we have pre-drafted decrees, ready for immediate signature. Yet, let me inquire: are you fully confident in your capability to assume control over production? Do you comprehend the intricacies of your output and its interconnection with both the Russian and global markets? Interestingly, it becomes apparent that they are not fully prepared for this task, and even Bolshevik literature does not encompass these aspects.”

As a result, for instance, the nationalization of the oil industry transpired with minimal involvement from Lenin. The architect of the revolution harbored the perspective that “this decision could potentially erode the foundations of the oil industry instead of revitalizing it,” given the paramount importance of this sector in ensuring an uninterrupted fuel supply for the nation. Discussion even emerged about the potential feasibility of soliciting foreign capital to facilitate the rejuvenation of the oil industry by offering concessions to Western nations for oil extraction.

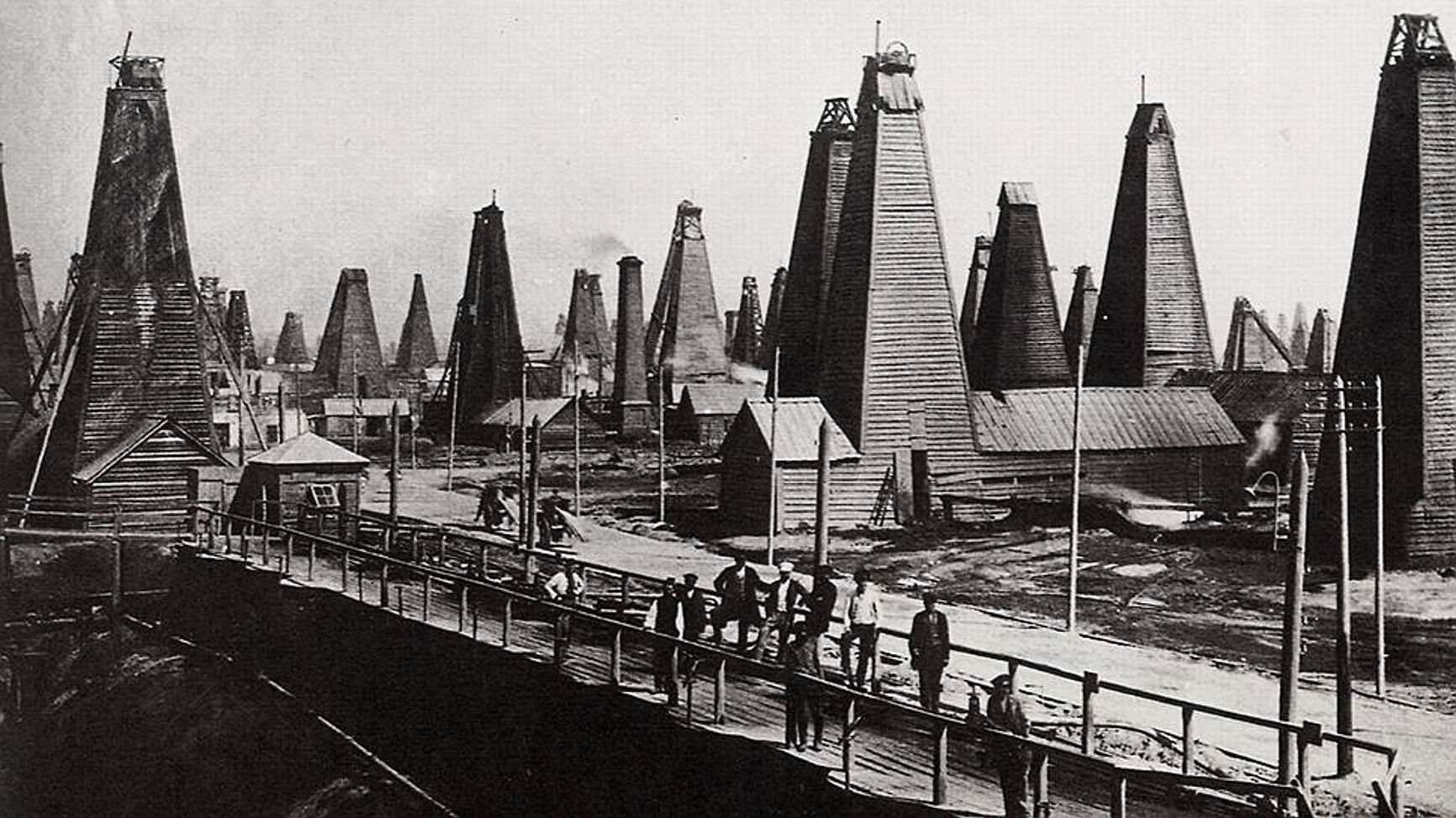

Oil rigs in Baku at the end of the 19th Century

Local perspectives differed in this regard. The authorities in Baku (notably, it was the Azerbaijani oil fields within the Russian Empire, which were the primary suppliers of oil) decided to nationalize the oil industry without central coordination. According to some historians, Stalin's intrigue played a role here; without Lenin's knowledge, he sent a telegram to Baku stating that the center had approved the nationalization. This tale vividly illustrates the lack of unity among the Bolshevik ranks on this matter.

How did nationalization unfold in practice? The management of nationalized enterprises was assumed by VSNKh (Supreme Council of the National Economy). For each enterprise, a commissar (a representative of state authority) and two directors – administrative and technical – were appointed. The administrative director (such directors were also referred to as the “red directors”) was typically chosen from party members, often from among workers or supervisors of the production. The technical director, on the other hand, was typically an “expert from the bourgeoisie,” a former chief engineer or manager. The Bolsheviks viewed this approach as a compromise, understanding that effective enterprise leadership required more than just party membership – knowledge and managerial experience were crucial. To facilitate centralized control under VSNKh, specialized departments were established, each responsible for a particular industry – such as the Metal Industry Department (Glavmetal) and the Textile Industry Department (Glavtekstil), and so on.

To prevent the paralysis of production due to nationalization, the decrees typically stipulated that “all administrative and technical personnel must remain in their positions and fulfill their duties.” Enterprises declared as nationalized were regarded as being “in gratuitous lease of the former owners” until specific instructions from VSNKh were issued for each of them. This placed more obligations than rights on the former owners: they were required to ensure the preservation and uninterrupted operation of enterprises that were essentially no longer theirs.

Nationalization across all sectors occurred without any compensation to the owners. Dealing with foreign-owned properties posed a greater challenge: initially, these were also nationalized without compensation. However, in the early 1920s, as Soviet Russia began to establish relations with Western countries, nationalized enterprises and compensations for them became significant bargaining points. Countries whose citizens had invested in the Russian Imperial economy demanded restitution for damages. Sometimes the USSR even agreed to concessions regarding compensations, but in practice, very few received such compensation.

The Likino Manufactory, the first nationalized enterprise

The Likino Manufactory in the Vladimir Governorate has entered history as the first enterprise to be nationalized by the Bolsheviks. The manufactory was established in the mid-19th century by Vasily Smirnov, a peasant of the Old Believer faith. At the time of nationalization, the production was overseen by his grandsons, Vasily and Sergey. Back then, the Likino Manufactory was a large integrated enterprise with paper-spinning, weaving, and dyeing factories, employing nearly 4,000 people. The Smirnovs made efforts to ensure the well-being of their workers, allocating funds for building exemplary workers' dormitories (equipped with plumbing, electricity, and even telephones), bathhouses, hospitals, and schools, all of which they financed themselves.

In the latter half of 1917, Sergey Smirnov decided to close down the production due to shortages of raw materials and resources. However, the manufactory workers believed that the factory owner was intentionally sabotaging production and lodged complaints against him with the new authorities. As a result, on November 17, 1917, well before the main wave of nationalization, Lenin personally signed a decree to nationalize the Likino Manufactory (with the condition “not to ask the government for money: there is none”).

Although the Likino Manufactory was allegedly nationalized to prevent its closure (and indeed, a month after nationalization, the halted factory resumed operations), its affairs did not proceed as smoothly as Soviet sources claimed later. In the years 1919-1920, the factory experienced several shutdowns due to the lack of raw materials and fuel. In June 1923, the Likino Manufactory was closed due to financial losses, though it was later reopened.

Sergey Smirnov, who was a part of the Provisional Government at the time of the revolution, was arrested in the Winter Palace after the Bolsheviks came to power. He spent some time in the Peter and Paul Fortress and then emigrated to Berlin at the beginning of 1918, where he led the Society for Assistance to Russian Citizens in Berlin.

The Abrikosov and Sons Partnership

The confectionery empire of the Abrikosov family began in 1804 with a small family workshop founded by a former serf (Abrikosov is a pseudonym derived from “abrikosovaya pastila” (apricot marshmallow), which was the most popular confectionery product at that time). By the time of the revolution, the Abrikosov and Sons partnership ranked among the top three largest Russian confectionery enterprises and held the title of Purveyor to the Court of His Imperial Majesty. By the early 20th century, the company employed 2,000 people, and its annual turnover in 1913 reached nearly 4 million rubles. An extensive infrastructure was developed around the production: a network of branded retail stores across the country, wholesale warehouses, a sugar plant, laboratories, dormitories, canteens, and hospitals for workers.

The company's product range comprised 230 varieties of confections: marmalades, marshmallows, marzipans, gingerbreads, caramels, biscuits, pastilles, jams, assorted candy boxes, chocolate figurines, and even prototypes of “Kinder Surprise” eggs. The Abrikosovs were particularly renowned for their glazed fruits, a product that had not been produced in Russia before them. To develop and refine the technology for fruit glazing, the Abrikosovs established a special laboratory headed by an expert from France.

On November 11, 1918, the assets of the partnership were nationalized. The main production facility of the Abrikosovs, the Moscow factory, was renamed to “State Confectionery Factory No. 2” (in 1922, it was named after the revolutionary Peter Babaev). The former owners were removed from management, although they remained in technical positions for a while. The new owners continued to benefit from the reputation of the old brand for a long time: on the labels of all products, after the words “Factory named after worker P.A. Babaev,” the phrase “formerly Abrikosov's” was invariably added.

One of the stores of the Abrikosov and Sons Partnership in Moscow

In the years immediately following nationalization, the factory's affairs took a turn for the worse. As a result, in September 1921, it was leased to private individuals, and production quickly improved: the factory resumed the production of candies, cookies, pastries, meringues, and caramels. However, in 1923, the factory was taken back from the lessees (simply by not renewing their lease) and transferred to the management of Mosselprom.

In 1928, following the dubious principles of planned economy, the authorities made the rather questionable decision to specialize all Moscow confectionery factories by product range: some would produce only chocolate, while others would focus solely on cookies. The Abrikosov (Babaev) Factory was designated for caramels. The production of other confections for which it had once been renowned came to a complete halt; equipment and specialists were redirected to other enterprises, and the unique technology of fruit glazing was forgotten, along with the 230 product varieties. For almost two decades, the factory produced only caramels. The chocolate, for which it later gained fame, only began to be produced there after the war, when equipment brought from Germany was introduced in the USSR.

As for the Abrikosov family, their paths diverged after nationalization. Some of the family members went to Paris, while others remained in the USSR. The founder's grandson, Professor Alexey Abrikosov, conducted the autopsy and embalming of Lenin in 1924.

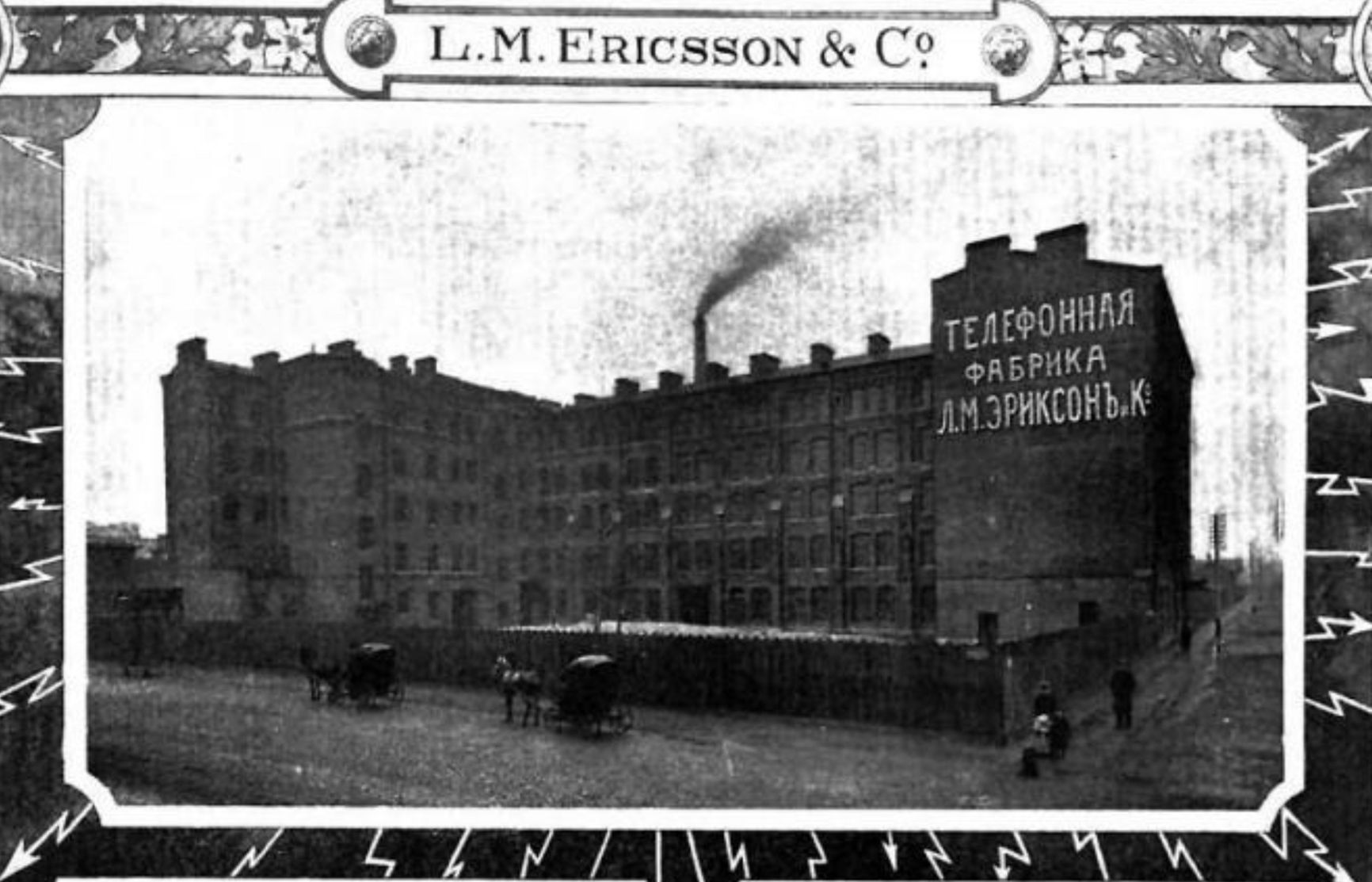

The Factory of the Russian Joint-Stock Company L.M. Ericsson and Co

The Swedish company Ericsson entered the Russian market in 1881, when its founder, Lars Magnus Ericsson, received an order in St. Petersburg to manufacture a small batch of telephones. At that time, the first telephone networks were just beginning to be established in the Russian Empire. Initially, Ericsson opened a relatively small production facility in St. Petersburg. However, as business flourished, the company regularly received government orders, and eventually, in 1900, it constructed and launched a huge state-of-the-art factory on Bolshoy Sampsonievsky Prospekt, known as the first overseas Ericsson factory. By 1917, the factory employed 3,500 people, twice the number at its main facility in Stockholm.

Following the revolution, the same director, the talented engineer and professor Lev Shpergaze of the Electrotechnical Institute, stayed on as the head of production. He continued in his position even after nationalization, which occurred in 1919, later than at other major enterprises,. As the electrical engineering industry was crucial for the Soviet government, the fate of the enterprise after nationalization turned out quite well. In October 1920, Lenin signed a resolution outlining measures for the restoration of the electrical engineering industry, which listed the enterprises to be prioritized for restoration. The Ericsson factory was among them.

Telephone Factory of the Russian Joint-Stock Company L.M. Ericsson and Co. — Krasnaya Zarya Factory — Ericsson Business Center

citywalls.ru

The Ericsson factory (now Krasnaya Zarya) became a leading enterprise in its field. It not only resumed the production of its previous products (by 1928, it was manufacturing 75% of the USSR's telephone products), but also began producing automatic telephone exchanges (ATEs). Simultaneously, the factory quickly established cooperation with its former owners, the company L.M. Ericsson, with the involvement of Lev Shpergaze, who maintained personal contacts with the management. It was the Swedes who helped to reconstruct their former factory in the mid-1920s, providing technical documentation for the production of ATEs and even training Soviet specialists at their own facilities.

Lev Ivanovich Shpergaze led the factory until November 1925, when he had to step down due to health reasons. In 1926, he headed the organizational department of Gipromez (State Institute for Designing New Metal Factories) and held this position until his death in 1927. He did not live to see the start of the Great Purge, which claimed the lives of his son (Lev Lvovich Shpergaze was repressed in 1934) and both directors who succeeded Lev Ivanovich at the former Ericsson factory (they were executed in 1937-1938).

The Shustov and Sons Partnership

The Shustov and Sons partnership was one of the largest alcohol producers in the Russian Empire. By the beginning of World War I, the Shustov family controlled 30% of the country's alcohol market. The society held the title of purveyors to the imperial court and owned several wine distilleries. Their most famous product was brandy (cognac). The Shustovs put significant marketing efforts to change the perception among their compatriots that their brandy was of lesser quality compared to French cognac.

In March 1918, the Shustov productions were nationalized. Their management took a rather peculiar turn: for instance, the Moscow plant, now named “Phosgene,” was initially tasked with producing synthetic aviation fuel (which failed), and later, alcohol production was established there in 1925. The fate of the most renowned Shustov plant, located in Yerevan, was no better. The authorities of the newly formed Armenian Republic had nationalized it. The production of high-quality brandy that once rivaled French cognac came to a complete halt due to a lack of raw materials and fuel.

A signboard with a Shustov and Sons product advertisement in Moscow

At the time of the February Revolution, the business was managed by the founder's sons. They reacted differently to the changes. Vasily Shustov, apparently the first to recognize the danger of the turbulent times, obtained permission to travel to the United States supposedly for equipment procurement via the Chemical Committee at the Main Artillery Directorate in September 1917 and did not return.

The other brothers attempted to fight for their possessions. They were among the few proprietors of nationalized enterprises who tried to contest the expropriation of their property. The Shustovs focused their efforts on the Yerevan plant, perhaps assuming that reaching an agreement with the Armenian authorities would be easier than dealing with the Bolsheviks in Moscow. Pavel and Alexander Shustov managed to arrange a meeting with members of the government of the republic and tried to prove that the plant's nationalization was illegal. According to Armenia's new laws, only those enterprises were subject to nationalization where the owners were either accused of actions harmful to the state or were absent altogether. However, the Armenian authorities did not wish to give up valuable production, and the Shustovs left the capital of the republic with nothing.

After all their assets were taken away, Pavel and Sergey Shustov remained in the country. Pavel Nikolayevich worked as a cashier at “Phosgene,” the former Moscow production facility, and Sergey Nikolayevich worked in Centrosoyuz (Central Union of Russia's Consumer Societies); in 1927, he published a handbook titled “Grape Wines, Brandies, Vodkas, and Mineral Waters.” As for the Yerevan plant, it became the main enterprise of the wine and brandy trust Ararat.

The Muir and Mirrielees Furniture Factory

While enterprises operating in crucial sectors for the Bolsheviks were supported and developed after nationalization (albeit not always effectively), industries producing non-essential goods (let alone luxury items) faced particularly difficult times.

The Muir and Mirrielees trading house was founded in Russia in 1857 by two Scotsmen, Archibald Mirrielees and Andrew Muir. Initially, the company dealt with haberdashery, but later expanded into furniture production. By 1914, Muir and Mirrielees owned a gigantic department store (with 80 departments and 3,000 employees) on Theatre Square in Moscow, as well as a furniture factory on Malaya Gruzinskaya Street. The factory produced luxury furniture (some of which was purchased by the imperial court) and other luxury items such as intricate parquet flooring, designer wallpapers, and book bindings.

Moscow, Theatre Square, Muir and Mirrielees Department Store. 1908-1910

Wikipedia Commons

In 1918, both the factory and the department store were nationalized. While the department store was eventually used for its intended purpose – it became the Mostorg department store and later the Central Department Store (TsUM) – the production of unique furniture was closed down. The building of the furniture factory was handed over to the Propeller aviation plant and was converted for the production of aircraft propellers.

By the time of the revolution, the Muir and Mirrielees founders had long passed away, and the company was managed by Philip Walter – the man responsible for its peak commercial success (he was the one who built both the furniture factory and the new enormous department store). After nationalization, Walter was dismissed and, a year later in 1919, he died in poverty. It was said that in his final months, he had to dine at the expense of his former employees.

Singer Manufacturing Company Plant

The sewing machines of the American company Singer captured the Russian market as early as the 19th century. However, there was one problem: delivering products from the USA to Russia was very expensive and time-consuming. The logistical challenges affected the retail price, and competing firms with lower prices began to enter the Russian market.

Therefore, the company's management decided that it would be more advantageous to establish its own production in the Russian Empire. In 1902, a plant was launched in Podolsk, which was supposed to supply sewing machines not only to the Russian market but also to Turkey, the Balkan countries, and China. By 1914, the Podolsk plant was producing 675,000 machines per year and nearly equaled the volume of American production. During World War I, it was partially reconfigured to produce ammunition.

Historical building of the Singer House in St. Petersburg, now a bookstore on Nevsky Prospekt

In November 1918, the Podolsk Singer plant was nationalized. However, it took five years to restore sewing machine production, which resumed only in 1923, although the production volumes were incomparable: in 1924, only 60,000 machines were produced – ten times less than in the last pre-war year.

While the previous production volumes were eventually reached in the 1930s, the plant remained technologically stagnant for a long time after nationalization. While in the West, the Singer company continuously modernized its production and released increasingly modern models, the machines of the Podolsk Mechanical Plant continued to resemble the pre-war “Singers.” Reconstruction only occurred after World War II, using equipment brought from the Singer plant in Wittenberg.

For the past one and a half years, pro-government media have been regularly publishing articles about Bolshevik nationalization, portraying it as a completely just and economically feasible decision. But even if one sets aside the question of fairness, Soviet nationalization rarely resulted in success and prosperity for the industries. More often than not, the opposite occurred, with flourishing enterprises either closing down or suffering significant declines in product range and quality.

To be more accurate, it was a matter of priorities. The new authorities were ready to invest in significant industries for the regime (for example, anything related to the defense complex). As for those who produced “luxury items” and “excesses” - and by Bolshevik standards, a significant portion of consumer goods fell into these categories - the authorities did not hesitate to intervene.