After Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Ukrainian army promised rewards to Russian military pilots who would defect and land their aircraft on Ukrainian-controlled territory. So far, no Russian has taken Ukraine up on the offer, but the prospect of defection isn’t as optimistic as it may initially seem. Multiple airmen have defected throughout Russian (or, rather, Soviet) history – for the pilots, it was a unique chance to overcome the Iron Curtain and continue their lives in freedom and prosperity, while for the West it was an opportunity to study the latest developments in Soviet military technology. Fugitive pilots were declared “enemies of the people,” and information about their escapes was carefully concealed. However, there were incidents that even Soviet propaganda could not keep quiet about. The Insider took a closer look at three of the most notorious pilot defection stories from the USSR.

Content

Yevgeny Vronsky: Su-7 crash landing in West Germany

Viktor Belenko: Hijacked MiG-25 to Japan

Alexander Zuyev: Opposed the party line and hijacked a MiG-29 to Turkey

Military pilots have used planes to escape to other countries ever since they were invented. The first aircraft hijackings in Soviet Russia occurred even before the formation of the USSR. The fugitives were then declared “enemies of the people,” and the Soviet authorities responded to the escapes by pressuring the governments of the countries harboring the runaway pilots. The Soviet push was undertaken not so much to return the equipment, but to convey the inevitability of punishment in order to intimidate all potential future defectors. The exact number of Soviet pilot defections is unknown, as not all incidents of this kind were made public – even in the foreign press. Soviet media and in socialist countries . Multiple Soviet landings at foreign airfields, which were nevertheless made public, were explained as “forced” or “emergency” landings due to a shortage of fuel, or as navigational errors. However, there were exceptions – incidents that even the Soviet Union could not conceal from the public due to their scale. Such were the escapes of three pilots – Yevgeny Vronsky, Viktor Belenko and Alexander Zuev.

Yevgeny Vronsky: Su-7 crash landing in West Germany

It was not always pilots who hijacked planes – sometimes it was those who maintained the equipment, like aircraft mechanics such as Yevgeny Vronsky. The 23-year-old lieutenant served at the Grossenhain airfield in East Germany, and had never flown an aircraft prior to the hijacking. Shortly before he fled, Vronsky had befriended an officer in a simulator class, and the latter occasionally let him use one of the training machines, allowing the mechanic to master the basics of taking off and manouvering the plane in the air. Vronsky never learned how to land, but that didn’t prevent him from going through with the escape.

There is no reliable information about the details of Vronsky's flight from the USSR – one can only rely on media reports. According to one of the most widespread versions, on May 27th 1973 – a day when no training flights were scheduled, with the overwhelming majority of servicemen performing routine maintenance work – Vronsky got into a Su-7 jet fighter and rolled it onto the runway. There is no exact account of how he managed to get into the plane. The servicemen and staff saw the aircraft coming out of the hangar and immediately realized that an amateur was in the cockpit. The final realization of what was happening only sunk in when Vronsky began to gain speed – at that moment, a group of technicians tried to block the runway with a car. Vronsky managed to manoeuver around it and continued gaining speed. The plane then took off and started its flight towards West Germany.

Vronsky did not retract the landing gear, apparently fearing that he would lose control of the aircraft if it became unbalanced. He flew at a minimum speed and at an altitude of only 500 meters, which meant the aircraft was difficult to detect for air defense systems – a fact that other defector pilots also took advantage of. The Soviet high command dispatched 32 fighters from six bases that day, but Vronsky was lucky – he remained undetected. In less than an hour, the fugitive aviation mechanic reached West German territory. Since he did not know how to land, he decided to eject. The plane fell into a wooded area near the town of Braunschweig, and Vronsky landed by parachute not far from the crash site. At first he met German civilians, who took him for a Soviet pilot who flew in from Syria by mistake, and offered the fugitive help. The aircraft mechanic soon fell into the hands of the German military.

Report on Vronsky's escape in the Braunschweiger Zeitung newspaper

The West German authorities did not want to strain the Soviet-German relationship due a visit by Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev a week before the incident – as such, the wreckage was returned to the Soviet side, but Vronsky remained in the FRG and was later granted political asylum.

The wreckage was returned to the Soviet side, but Vronsky remained in the FRG and was later granted political asylum

Although Vronsky was promised a safe stay in Europe, he refused to make any political statements. In one of his few interviews he stated only that his escape was a deliberate and conscious decision.

The base from which Vronsky escaped questioned the flight simulator personnel, discovering that the hijacker had used the training device more than the pilots themselves. Access to the simulators for technicians and other non-pilots was banned, while much of the staff serving at the Grossenhain base was transferred to other military installations.

The most unusual aspect of the escape was that the Su-7 aircraft – a plane that was rightly considered difficult to fly – was manned by someone without any flying experience. The fact undermined the plausibility of Vronsky’s escape, which was called into question by specialists and professional pilots alike for years after the event took place.

Viktor Belenko: Hijacked MiG-25 to Japan

The most famous escape in the history of Soviet aviation was that of Viktor Belenko. The pilot himself became a global celebrity, with major Western media outlets reporting on him for years following his defection – even Soviet and Russian propaganda could not forget the “traitor pilot” decades after the escape. Even with the onset of Vladimir Putin's rule, Russian TV continued to produce propaganda documentaries vilifying Belenko, as the Soviet pilot managed not only to flee to the West, but also turn over the then-new Soviet MiG-25P fighter jet to the US and reveal secret information about the Soviet armed forces. Due to the popularity of the incident, much more is known about Viktor Belenko's biography, including his childhood and personal life, than about the other renegade pilots.

Viktor Belenko's military ID

The future fugitive, son to a Ukrainian father and a Russian mother, was born in Nalchik, the capital of Kabardino-Balkaria. After his parents divorced when he was two years old, he was abandoned by his mother and brought up first by his relatives and then by his father and stepmother. In 1971, Belenko graduated from the Armavir military aviation school, and went on to serve in the Stavropol region, later being transferred to the Far East at his own request. Throughout his military service, Belenko was never reprimanded, and received positive evaluations from his superiors. Belenko was also a member of the Communist Party, was elected a member of the Komsomol (Communist Youth League) and Party bureau. Special services rarely suspected such people as Belenko of disloyalty, but, as it would later turn out, Belenko had been contemplating an escape plan for several years, all the while cultivating an image of a Komsomol member devoted to the Soviet system. Him having a young wife and child, whom he had left behind in the Soviet Union, also did not affect his decision to escape.

In the Far East, Viktor Belenko began flying the MiG-25P fighter-interceptor. The clearance to fly near Japan turned out to be an additional incentive for the pilot to flee abroad, and sealed the MiG-25P's fate as the plane to take Belenko over the Iron Curtain.

The MiG-25

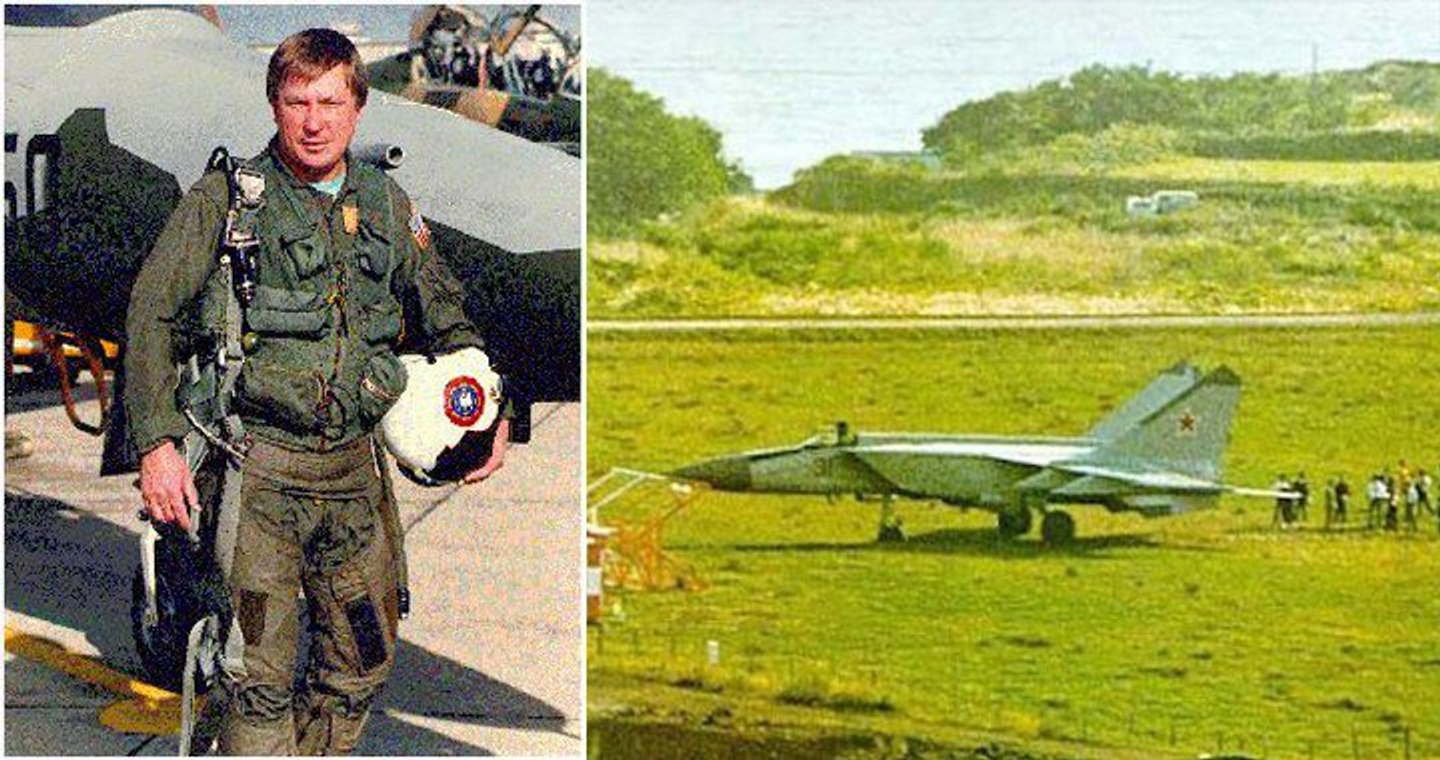

At 6:45 a.m. on September 6, 1976, Belenko took off from Sokolovka airfield for a flight exercise paired with another fighter. Like Vronsky, Belenko knew how to avoid radar detection – by flying as low as possible. After falling behind the lead pair, Belenko descended and maintained an altitude that would avoid detection by both Soviet and Japanese air defense systems.

At 7:40, the fighter flew over the Soviet-Japanese border. After entering Japanese airspace, Belenko reached an altitude of about 6,000 meters and was picked up by Japanese radars. The Japanese were not able to communicate with the Soviet pilot, as the MiG-25 radio was set to a different frequency. Japanese fighters took to the air to intercept the unknown intruder, but by the time they reached his location, Belenko had again slipped off the radar.

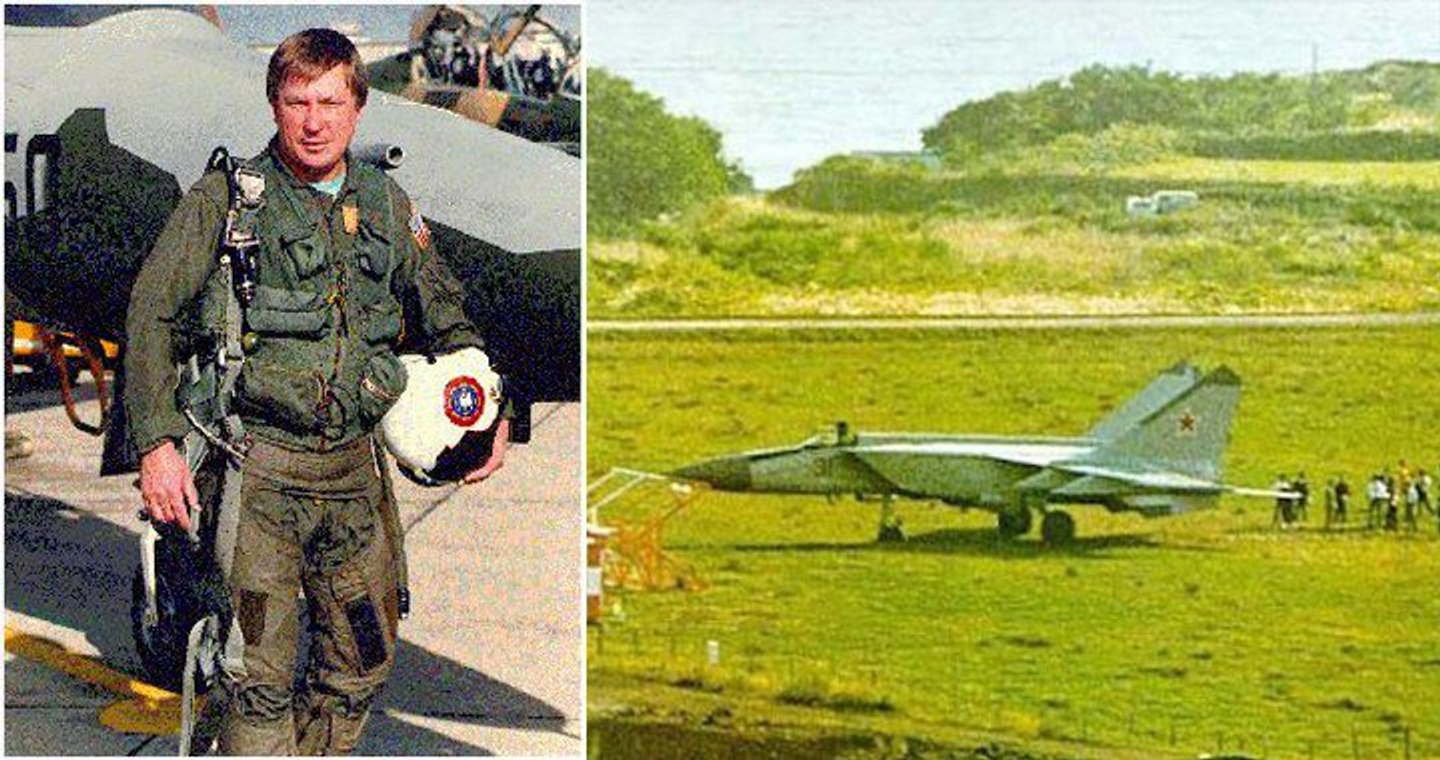

The plane planned to land at Bitose airbase, but was forced to land at the nearest airfield, Hakodate in Hokkaido, due to a fuel shortage. As the runway was not long enough, the MiG-25 rolled out of the runway and approached the boundary of the airport. Belenko got out of the cockpit and fired two warning shots from his pistol as motorists on a nearby highway took pictures of the scene.

Hakodate airport in 1976

At 9:15, Japanese radio broadcast that MiG-25P number 31, piloted by Soviet pilot Belenko, landed at Hakodate airport. Japanese authorities later officially announced that Belenko had applied for political asylum. On September 9, he was evacuated to the United States. The aircraft was disassembled, subjected to detailed examination by Japanese and American specialists and returned to the USSR on November 15, 1976. Belenko protested against the return of the plane, advising the Americans to leave it for study for another couple of years. In the USSR, the stolen MiG was reassembled, but it was not allowed to fly and was used as a training aid at an aviation academy in Daugavpils.

The Soviet authorities did not officially respond to Belenko's escape until three weeks after the incident. On September 28, 1976, state news agency TASS distributed a press release with the Soviet Foreign Ministry’s official reaction to the hijacking of the fighter jet. As in all other cases, it stated that Belenko's plane had made a “forced” landing abroad. On the same day – September 28 – a press-conference was held with the wife of the pilot and his stepmother in Moscow. The women tearfully asked Viktor to return home. Belenko’s wife claimed that her husband “would be pardoned even if he made a mistake.” L. Krylov, a representative of the Soviet Foreign Ministry, also gave guarantees of Belenko’s safety upon his potential return.

The Soviet authorities did not officially respond to Belenko's escape until three weeks after the incident

On September 19, George W. Bush, then director of the CIA, called the incident an “escape” and a “major intelligence success,” adding that US intelligence officials were successfully cooperating with the defector.

Soviet and later Russian propagandists argued that the United States not only borrowed design ideas, but even created their future fighters based on the MiG-25. US authorities, however, voiced a completely different story – after analyzing the plane, American technical experts came to the conclusion that the MiG-25 was not suitable to intercept high-altitude SR-71 American spy planes. The plane was inferior to the SR-71 in terms of its technical and until 1976 characteristics, and its speed parameters were dismissed as a propaganda gimmick to increase its export appeal as “the second fastest aircraft on the planet.”

Belenko's plane in Japan

As noted by Flightglobal editor Stephen Trimble, the US military and political leadership did not sanction SR-71 reconnaissance flights over Soviet territory until 1976, as they were unsure that the USSR had no equivalent interceptors. These fears were dispelled thanks to Belenko's escape. The Americans were also able to familiarize themselves with the aircraft's weapons control system and obtain reliable technical data on its actual combat capabilities – a valuable asset in terms of refining their own military aircraft to a level that would effectively oppose or surpass that of the MiG.

Belenko's hijacked MiG-25P

While abroad, Viktor Belenko, unlike Vronsky, spoke about the motives for his escape in great detail. He cited discontent with the standard of living in the USSR and the poor conditions of service in the armed forces as the two main reasons for his flight.

Viktor Belenko, unlike Vronsky, spoke about the motives for his escape in great detail

The motives of Belenko's escape were also revealed in the Soviet investigation of the incident, which noted that the pilot began acting strangely around July 1976. He became nervous and agitated, and was seriously distressed about a delay in his promotion to the rank of captain and an appointment as squadron chief of staff – a position he was earlier promised.

Viktor Belenko (left)

Unlike other defectors, Viktor Belenko made no attempts to reunite with his family. He ignored appeals made by Soviet intelligence agencies on behalf of his relatives to establish his whereabouts. He said that he hated his wife, described his relationship with his stepmother as cold, and claimed that the last time he saw his three-year-old son Dmitry was before his mother-in-law took him away to “take charge of his upbringing.”

Victor Belenko's wife and stepmother hold a press conference

After his arrival in the US, Belenko decided to stay in the country to build a new life for himself. The former Soviet pilot actively cooperated with US special services, telling them everything he knew about the USSR’s military and aviation. Belenko told the US that he was ready to cooperate, and for that he wanted to visit an American airbase and an aircraft carrier, not model ones, but the first ones he saw. Belenko was curious, as he wanted to find out the real state of affairs in American air units and compare what he saw with what he had learned from Soviet propagandists. His wishes were soon fulfilled. In late 1976, he visited the US Air Force base in Langley. The shock and amazement of the Soviet pilot had no limits – at the base Belenko was shown practicing piloting skills in a flight simulator. Viktor said that in the Soviet Union, flight simulators were there not to train pilots, but to merely create the appearance of training.

F-16V simulator

Belenko was also struck by the informality in the relationship between enlisted and noncommissioned officers. He was able to visit the airbase compound, the soldiers' and their families' living quarters, and witness the comfortable living conditions of the American troops. On leaving the airbase, Belenko shared his thoughts aloud with his companions, “If my regiment had looked at what I saw today even for five minutes, a revolution would have begun.”

In January 1977, Viktor Belenko visited the aircraft carrier USS John F. Kennedy, anchored at Norfolk Naval Base. According to Rear Admiral Roger Box, Chief of the Fighter Bomber Course, Belenko was so enchanted by the sight of aircraft taking off and landing, coupled with the coordinated work of maintenance personnel on the deck of the aircraft carrier, that he declined an offer to go down to his cabin for the night – he decided to spend the night directly on deck, observing the flight process at night. As he left the ship, he confessed that at first he suspected that everything he had seen had been set up especially for him, but after watching the planes take off and land throughout the day and night, he decided that it would have been too complicated to organize such an air show just to impress him.

Belenko at first suspected that everything he saw was set up especially for him

Retired aviation colonel George Wish was asked to take care of Belenko at his new place of residence to help the Soviet pilot adapt to his new life, as he had never seen an American supermarket before and only learned about the US from Soviet media coverage. Despite the difference in age and rank, the two became good friends.

After some time had passed, Wish considered his mentee adapted enough to travel around the country on his own and gave him the keys to his Dodge Charger, encouraging him to discover America. Belenko followed his advice and toured the country, where he met his future wife, who was working as a waitress in a diner at the time. Wish regularly visited his former mentee.

Belenko's escape also contributed to changes within the USSR itself – all single, divorced and other “morally unstable” and “promiscuous” pilots were banned from flying, and were instead transferred to other positions not connected to manning airplanes. Commanders were instructed to identify these pilots and remove them from flying, with a direct order not to spare anyone, and hand over potential suspects to the authorities without hesitation.

Belenko's escape also had economic consequences. The Soviet government tried to put pressure on Japan, threatening to unilaterally terminate contractual obligations under bilateral foreign trade agreements if the pilot and his plane were not returned. Some of the potential sanctions included blocking Japanese investment in the Soviet economy, stopping Japanese participation in the construction of Soviet woodworking and pulp-and-paper industries, and in the exchange of nuclear energy technologies.

However, it would be unfair to argue that the consequences of Belenko's escape for the USSR were only negative. Indirectly, the incident accelerated the adoption of a new aircraft model, the MiG-31. The MiG-25 was then exported to other socialist countries before it became completely obsolete. Also in the USSR, the deviations in the actions of the party and official elite, which by that time had become systematic and widespread, were examined and uncovered. Senior officers of the Soviet Air Defense Forces, who were found responsible for the escape, were also reprimanded and punished. Belenko himself was convicted for treason in absentia by the Supreme Court of the USSR and sentenced to death.

Alexander Zuyev: Opposed the party line and hijacked a MiG-29 to Turkey

Belenko's escape, in spite of the enormous number of cautionary measures taken after the incident, did not prevent further aircraft hijackings in the USSR. A sense of injustice observing the country's political events, and receiving criminal orders in the process, pushed the pilots to escape. One such example was the incident involving Aleksandr Zuyev, who hijacked a MiG-29 fighter jet to Turkey.

He graduated from the Armavir Higher Military Aviation School in 1982, going on to serve in the 176th Fighter Aviation Regiment and pilot the MiG-23M. Zuyev had the honour of being among the first pilots in the regiment to begin retraining on the new MiG-29 fighter – according to the pilot, this enabled him to avoid being sent to the war in Afghanistan. However, there were also reports that the regiment would not be deployed to the Soviet-Afghan war.

Alexander Zuyev

Having made it to the West , Zuyev said that he was gradually becoming disillusioned with Soviet society and system. In his own words, the events of April 9, 1989 in Tbilisi – when an anti-Soviet, pro-independence demonstration was brutally crushed by the Soviet Army, resulting in 21 deaths – were the last straw. At the time, Zuyev was still serving in the 176th Fighter Aviation Regiment at the Mikha Tskhakaya airfield in Georgia. He initially thought about leaving the armed forces, but eventually decided to steal the newest Soviet fighter aircraft and defect to the West.

The day before his defection, he baked a large cake, having mixed a large amount of sleeping pills in the batter. The following day – May 20, 1989 – he announced that his wife was due to give birth to a boy (who was actually born a few days later), and invited the personnel in his regiment to celebrate. During the party, Zuyev handed each coworker a slice, except for four people: the commander who was preparing a flight plan, two mechanics on guard duty, and a unit member who was expected to be at another base.

With everyone asleep, Zuyev cut the telephone lines, then approached the aircraft, but two sentries would not let him near the airplane. Zuyev returned and waited past the shift change time. The second shift was incapacitated, so one of the sentries went to the squadron to check on them. While he was gone, Zuyev approached the airplane and informed the mechanic on guard duty that his replacement would be late and that Zuyev would fill in. This mechanic, already upset about his relief being late, was happy to hand Zuyev his assault rifle and walk away.

The other mechanic found everyone asleep at the squadron, and became suspicious of a problem. He returned to the airplane and confronted Zuyev. Zuyev tried to disarm the mechanic, but failed, shot him with a pistol and wounded him. Zuyev was wounded in the right arm.

The planes on duty were almost prepared for take-off, and Zuyev hijacked one, speeding off the runway. After take-off, he had planned on shooting the planes on the ground so that they would not try to intercept him, but failed as he forgot to remove one of the two locks on the gun.

The MiG-29 – the plane Alexander Zuyev hijacked to Trabzon

He then flew 240 kilometers (150 miles) south across the Black Sea to Trabzon, Turkey, where the aircraft was impounded. His first words at the Turkish airfield were, «Finally, I - an American!» Zuyev had apparently said the phrase to an airport guard who approached the plane so that the US embassy would be notified of his arrival. Zuyev was tried in Turkey on charges of hijacking the plane and acquitted, with the court finding his actions to be political in nature. Turkish authorities returned the plane to the Soviet Union on the following day, while Zuyev was granted political asylum in the US.

Zuyev, like Belenko, later advised the US Air Force. In particular, he took part in Operation Desert Storm, helping the US detect the radars of enemy MiG-29s. In 1992, together with Malcolm McConnell, he published a book about his escape, Fulcrum: A Top Gun Pilot's Escape from the Soviet Empire.

On 10 June 2001, Alexander Zuyev died in a plane crash, when his Soviet Yak-52 training aircraft stalled and fell to the ground 160 kilometers (100 miles) outside Seattle.