Putin is often compared to Nicholas I. The 30-year reign, the conservative tightening of the screws, the failed Crimean War. If we take a closer look at the last years of Nicholas's rule, the so-called “grim seven years,” the parallels become even clearer: the tightening of censorship, the persecution of the universities, threats to confiscate property from immigrants, and the struggle against Western influence. This period is commonly seen as the “darkness before the dawn” - the excessive conservative clampdown only brought the long-overdue sweeping reforms closer. But this optimistic scenario raises serious doubts, as relevant today as ever.

Content

Putin's Authoritarianism and the “grim seven years”

Dostoevsky

Turgenev

Herzen

“The darkness is stronger before the dawn”

Putin's Authoritarianism and the “grim seven years”

Understanding the war in Ukraine, which has been going on for almost a year now, is a process that takes place on many levels. One of them is historical analogies, which allow us to better understand the nature, causes, and mechanisms of the tragedy that is unfolding before our eyes.

Before February 24, 2022, observers and commentators most often compared the “late-Putin regime” of the late teens and early twenties with the Brezhnev stagnation, implicitly alluding to the inevitability of future perestroika. Now, however, it turns out the term was a misnomer, and that the “late” regime, with foreign agents and the suppression of recent rallies for Navalny, was not yet a “late” Putin regime.

Before February 24, the “late-Putin regime” was compared to Brezhnev's stagnation, but the term was a misnomer

Sometimes parallels were drawn with the contemporaneous popular democracy regimes (GDR, Czechoslovakia, Poland), which institutionally were indeed more like Putin's Russia, with their decorative multiparty systems and elements of a market economy. Less often - with late authoritarian regimes on the “outskirts” of Europe (Franco in Spain, Salazar in Portugal, the “black colonels” in Greece).

With the beginning of the full-scale Russian offensive and the rapid changes in Russian domestic politics that followed, popular analogies shifted back half a century and now comparisons were made with Stalin's Soviet Union and Hitler's Germany.

Perhaps the most accurate parallel is the Nicholas I era, including the Crimean War, in which England and France defeated Russia, and the years of tightening of the screws that preceded it, the so-called “Grim Seven Years.” Putin used to be compared to Nicholas I, who, as Pushkin put it, had “a lot from the ensign and a little from Peter the Great.” This analogy has become increasingly obvious of late.

Putin is often compared to Nicholas I, who had “a lot from the ensign and a little from Peter the Great”

The narrative of the “grim seven years” itself exists in a rather simplified form (usually mentioning a few particularly repressive years on the eve of the inevitable collapse of Nikolai's Russia and the inevitable “Great Reforms” that followed), but history gives us new reasons to look at this period more closely.

To begin with: what is the grim-seven-years period? Chronologically, it describes the period of Russian history from 1848 to 1855, when dissent and civil liberties were particularly suppressed and restricted.

The literary critic Pavel Annenkov described that period as follows:

“It's hard to imagine how people lived then. People lived as if in hiding. In the streets and everywhere the police reigned, both official and simply amateur, and the appetites for robbery, profiteering, self-enrichment through the state and public service developed to an unimaginable degree. They were even encouraged. A lot was going on then under the guise of good rules, blameless career progression, superior dignity! The three million stolen by Politkovsky from invalids, one might say, under the noses of all the authorities, paled in comparison with what the men of power did in general.”

During this period Russian subjects were practically forbidden to go abroad. Those who had left earlier were ordered to return under the threat of confiscation of their property, particularly income-generating estates.

Russian subjects were practically forbidden to go abroad. Those who had already left were ordered to return

At the same time, entry of foreigners into Russia was made more difficult; in addition, the importation of foreign books was effectively prohibited.

Double censorship was introduced in the country: the so-called Buturlin Committee (named after Senator Dmitry Buturlin, who headed it) rechecked publications that had already been censored. The committee even suggested that the liturgical text, the Akathist of the Protecting Veil of the Most Holy Mother of God, be revised to remove the “offensive” lines about the “invisible taming of the rulers of the cruel and bestial”. The Brockhaus and Efron encyclopedia wrote fifty years later: Buturlin jokingly said it would be a good idea for the censors to tweak the Gospel as well.

Nikolai Nekrasov would later write about Buturlin in his poem about Belinsky:

Ardent fanatic Buturlin,

Who, without sparing his bosom,

Was repeating one thing in rage:

“Close the universities,

And evil will be stopped!”

And indeed: the question of closing the universities was seriously considered, but the tsar did not go for it. As a result, all the universities, except Moscow's, limited the number of seats to no more than three hundred. Tuition fees were also raised, and the supervision of students and professors was ramped up.

In addition, the Minister of Education was replaced. The author of the Orthodoxy-Autocracy-Nationality doctrine Sergei Uvarov was dismissed as too liberal and replaced by Prince Platon Shirinski-Shikhmatov, who demanded that all sciences should be henceforth based “on religious truths in connection with theology.” He banned the teaching of philosophy, political economy, and foreign law.

Minister of Education Shirinski-Shikhmatov banned the teaching of philosophy, political economy, and foreign law

It came to ridiculous things. Shirinski-Shikhmatov tried to prohibit the transcription of Greek names “according to Erasmus.” For example, he demanded that Homer be called exclusively Omir (in the Greek manner). Notably, even though both forms existed in Russian literary language before the prohibition (for example, Baratynskiy wrote: “But green are the hills, forests, and banks of azure rivers in the fatherland of Omir”), after the prohibition this form ceased to be used at all as the data from the National Corpus of the Russian Language shows.

Like today, the “tightening of the screws” primarily affected those who “stuck out” more than others and allowed themselves, in the opinion of the authorities, more than others. If today it is not only writers whose books have been removed from libraries or wrapped in “foreign agent” covers, but also journalists, bloggers, actors, musicians, who have been accused of “betraying the country” in person or in absentia, “awarded” the status of a “foreign agent” and so on, back then primarily writers were affected. The “grim seven years” can therefore be most vividly and conclusively illustrated by three historical and literary examples: Dostoevsky, Turgenev, and Herzen.

Dostoevsky

The critic Annenkov, already mentioned above, called the “grim seven years” “the realm of gloom” precisely in the context of Dostoevsky's harsh court sentence.

Together with the members of the Petrashevsky circle, the young but already popular writer Dostoevsky, who hadn't even been a member but rather an occasional visitor, was arrested in the early morning of April 23, 1849, and sent to the Petropavlovsky fortress for eight months.

The Petrashevites' case was based on the reports of a police agent, Peter Antonelli, who was also a member of the circle. On the basis of his reports, Ivan Liprandi, on behalf of the Minister of Internal Affairs, drew up a report, which eventually reached the tsar's desk.

This document stated, inter alia:

“...From all this I derived the conviction that it was not so much a petty and isolated conspiracy as a comprehensive plan for a general movement, a coup and destruction.”

The November 13, 1849 court sentence was commensurate with the guilt actually invented in Liprandi's report:

“The military court finds the defendant Dostoevsky guilty of having received in March of this year from Moscow ... a copy of the criminal letter by the writer Belinsky – he read this letter in meetings... Therefore, the military court sentenced him for failure to report on the distribution of the criminal letter by the writer Belinsky about religion and government... to deprive him... of his rank and all rights of estate and subject him to the death penalty by shooting”.

At the same time, four days prior to the scheduled execution, Dostoevsky's death sentence was de facto commuted “due to its inconsistency with the guilt of the condemned.” At first it was planned to substitute the execution with eight years of hard labor, but the tsar personally commuted it to four years in prison followed by military service as a private.

Naturally, neither Dostoyevsky nor the others were informed of the decision. They were convinced that they were going to be executed “by firing squad,” right up to the announcement on the Semyonovsky Platz.

Dostoevsky in hard labor camp. K.P. Pomerantsev. The Feast of Christmas at the Dead House. 1862

Contemporaries were shocked by the barbaric show. One of the convicts, Nikolai Grigoriev, could not stand it and went insane. Dostoevsky himself later described his feelings in The Idiot, in the words of Prince Myshkin. He himself was also deeply affected by all this, both physiologically (his bouts of illness intensified) and ideologically (he underwent a conservative and religious transformation similar to the one described in the Crime and Punishment finale).

Turgenev

In 1869, a collection of literary works by Turgenev, then a living classic, was published. He was in his fifties, Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky were crowding him on the literary Olympus, and the critics and public did not take kindly to his recent novel, “Smoke”, finding it, to put it mildly, rather polemical and journalistic than artistically great.

So, Turgenev turned to the past. For his collected works he wrote a literary memoir - about Zhukovsky, Lermontov, Krylov and others.

He began, of course, with Gogol. He described how in 1851 he went to visit the terribly withered Gogol on Nikitsky Boulevard, how six months later Gogol died, and how Ivan Sergeyevich himself was arrested for a month for Gogol's obituary he wrote, banned by censorship, and then exiled to his estate near Oryol.

Count A.P. Tolstoy's house on Nikitsky Boulevard, where Gogol lived and died. Photo taken in 1901

Turgenev wrote:

“But all for the best; being under arrest and then in the countryside did me an undoubted good: it brought me into contact with those aspects of Russian life which, in the ordinary course of things, would probably have escaped my attention.”

Turgenev was already under close surveillance. Even his innocuous book “Notes of the Hunter” was scrutinized by the censors. A report has survived, in particular, which suggests that Ivan Sergeyevich deliberately “poetized the serfs” and showed that they, too, were human beings in order to thereby implicitly call for the abolition of serfdom.

Moreover, during the European revolutions of 1848, Turgenev went to Paris with Belinsky. He witnessed the killing of hostages, the crossfire, and the construction and fall of barricades. He did not like that at all and developed a lifelong aversion to revolution as an idea - he was rather a moderate liberal.

But during the “grim seven years,” aversion was not enough to prove loyalty. On April 28, 1852, Turgenev was arrested and sentenced to a month's imprisonment in the Admiralty (there was even a pun around Petersburg: “They say that literature is not respected here - on the contrary, literature is held under guard”), and then exiled to his family estate near Oryol under police surveillance.

The reason for the arrest was a formal violation of the censorship rules. To be more precise, it was not even a violation, but a trickery of sorts.

The fact is that after Gogol's death Turgenev wrote an article – an obituary – and tried to publish it in the Peterburgskie Vedomosti but was refused by the censor. There was nothing censurable in the text. Historians argue that either the censor was embarrassed by the word “great” in reference to Gogol (meaning that it was for the tsar to decide who was great and who wasn't), or there was an unspoken ban on mentioning Gogol in the press (after the deaths of Pushkin and Lermontov, censors had acted in a similar manner).

But Turgenev really wanted to publish his text. And he sent it to the Moskovskie Vedomosti, where the censors let it through (the two departments simply failed to coordinate their work).

Interestingly, for the sake of Turgenev, they even imposed a temporary ban on visiting those arrested in the Admiralty. Too many people wished to express their support for him every day.

Herzen

In 1849, at the request of Nicholas I, all the property of Alexander Herzen and his mother in Russia was arrested. Arrested informally, the court decision would not come until December 1850.

The reason was very simple. Herzen actively participated in the European revolutions - and refused to return to Russia. Having been pronounced an “eternal exile” (as the court noted in the verdict), Herzen nevertheless found a way out. He wrote about it as follows:

“I met Rothschild and asked him to exchange two Moscow Treasury bills [against the pledge of the estate]. Business, of course, was bad back then, the exchange rate was measly; the conditions he offered me were unprofitable, but I immediately agreed.”

Herzen managed to get some of the money. Following the advice of James Rothschild, he used it to “buy American securities, some French securities, and a small house on Amsterdam Street, occupied by the Havre Hotel.”

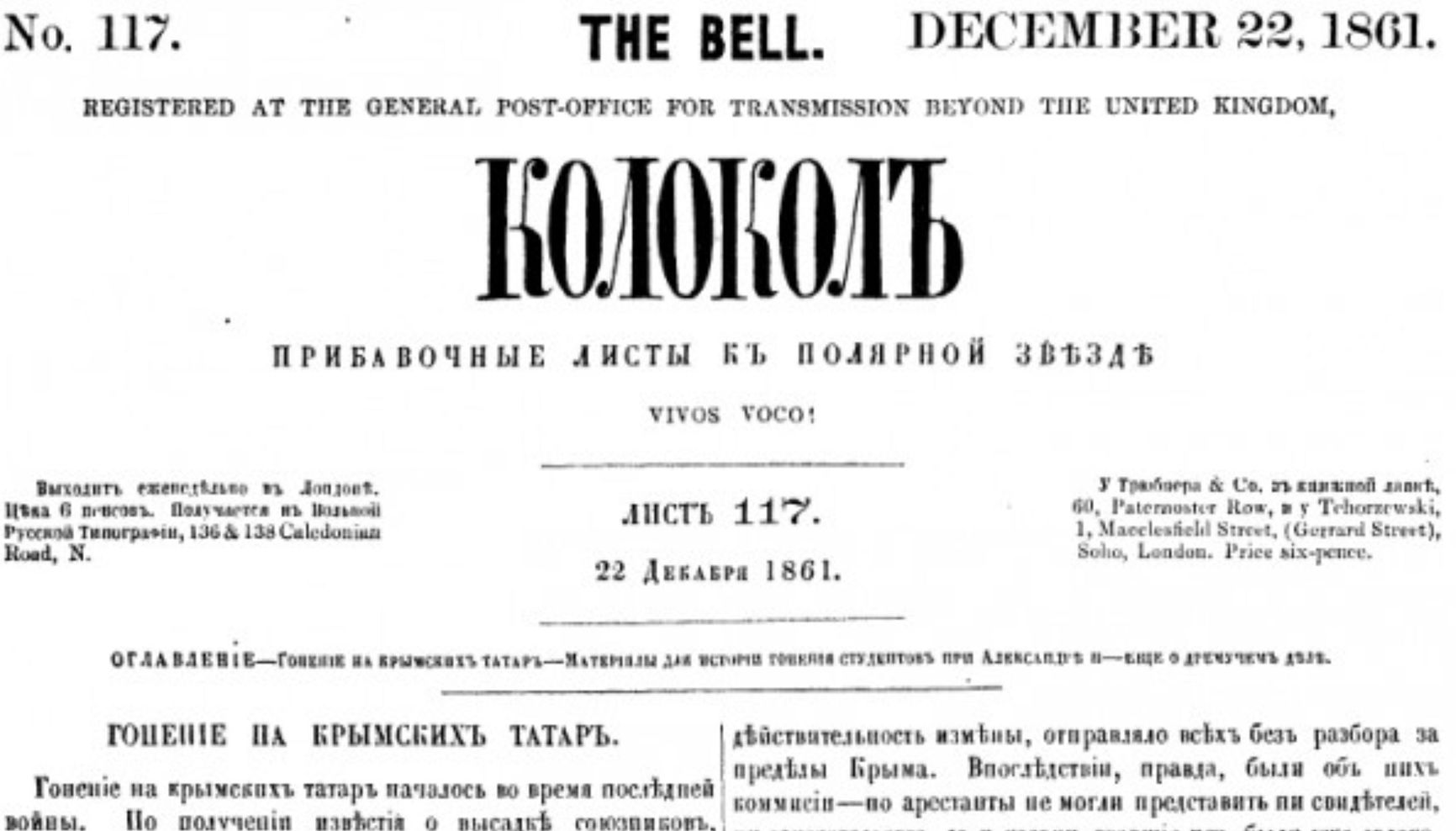

Title page of the Bell magazine

But there were problems with the cashing of the remaining securities. When the banker's agents applied to the Russian government in order to receive money for the bills, they were refused on the grounds that the property had been seized. We know of the conversation that took place afterwards between Herzen and Rothschild from the writings of Herzen himself:

“To me,” I said to him, “it is little wonder that Nicholas, as a punishment to me, wants to steal my mother's money or use it as bait to catch me; but I could not imagine that your name would have so little weight in Russia. The bills are yours, not my mother's; when she signed them over, she gave them to the bearer, but since you put your signature on them, you are the bearer, yet they've given you an impudent answer: the money is yours, but the lord won't pay.”

Herzen had been teasing the banker in this way for several days. He even described Russian politics with the phrase “Cossack communism.”

Eventually Rothschild decided to put pressure on St. Petersburg because his reputation was at stake; on top of that he was lending money to the Russian government at the time. By obtaining an audience with Count Nesselrode, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Empire, the banker effectively forced Nikolai's government to pay a comparatively small sum in order to obtain much larger sums, and Herzen received his money, which he later used to open the free printing press where The Bell was printed. One might even say that it was the tsar who financed The Bell.

“The darkness is stronger before the dawn”

Curiously enough, the “grim seven years” is a specific term that exists almost exclusively in Russian historiography. In English-language literature, for example, the dark seven years or grim seven years are mentioned very rarely-and only as a retelling of what this term is used by Russian historians.

In Western historiography, however, the entire thirty-year reign of Nicholas I is traditionally described as a single authoritarian continuum, as a period of freezing and repression.

It is likely that the more complicated domestic distinction (singling out of the most authoritarian stage of an already authoritarian rule) stems from a desire to distinguish “shades of gray,” on the one hand, and draws on a living historical and literary tradition, on the other hand.

“Whoever did not live in 1856 in Russia does not know what life is,” wrote young Leo Tolstoy, paraphrasing a French phrase about 1793. And he was, of course, expressing the general mood. Despite the very painful defeat in the Crimean War, the whole country was rejoicing and waiting for change.

Despite the very painful defeat in the Crimean War, the whole country was rejoicing and waiting for change

It is against this background of the subsequent death of Nicholas I, the defeat in the war, the anticipation of reforms, and the “Great Reforms” themselves that the “grim seven years” are noticeable.

Because of this, a narrative developed retrospectively that the grim period was programmed not to last very long. This idea was most lucidly expressed by the early twentieth-century literary critic Ivanov-Razumnik:

“...The pressure immediately and suddenly increased so much that it obviously could not last too long; in the hopeless gloom one could feel the light approaching, but to see it, one had to endure seven black, hard years.”

There is a logical fallacy here. Because things happened in a certain way, it doesn't mean they were supposed to happen that way. The death of Nicholas I, accidental in a sense (he dressed lightly and caught a cold at the parade), was not at all something to be expected. He reigned for thirty years, but he was only 56. Even with the poor development of medicine at that time, he might well have remained on the throne for another 15 or 20 years, and nobody and nothing could have seriously interfered with that. And then the “grim seven years” would have turned into a grim twenty-seven years. Dostoyevsky would have remained in Kazakhstan, Turgenev would have remained at his Oryol estate, and the peasants would have remained serfs.

Stories that fall within the overall “darkness is stronger before dawn” framework are especially well told in retrospect – as Turgenev did in his memoir. From within darkness, it is very difficult, if not impossible, to know how soon it will end. Turgenev, when he was serving his one-month prison sentence, let alone Dostoevsky, when he was in the hard labor camp, hardly imagined that things would be different in a couple of years.