Russia’s federal budget is being rewritten on the fly. Although the final deficit for 2025 remains to be seen, the country’s Finance Ministry has released the draft budget for 2026, which includes a frank note saying that revenue generated from tax hikes will go toward military spending. Russia needs to squeeze as much money out of its economy as possible, regardless of the consequences. “The horse has already been run ragged,” remarked Putin-linked oligarch Oleg Deripaska, who expressed dissatisfaction with the planned investments. In his words, “spurring” the economy will not yield a positive outcome.

Content

Population and businesses to shoulder war costs

Lies as state policy: the parable of not raising taxes

Fictitious reduction in defense spending

Living on borrowed time

Population and businesses to shoulder war costs

On Sept. 24, Russia's Ministry of Finance stated the goals of its 2026 budget: “The strategic priority is to ensure funding for the country’s defense and security needs, as well as social support for the families of participants in the ‘special military operation.’” Russia is also introducing several amendments to the Tax Code to “finance defense and security.”

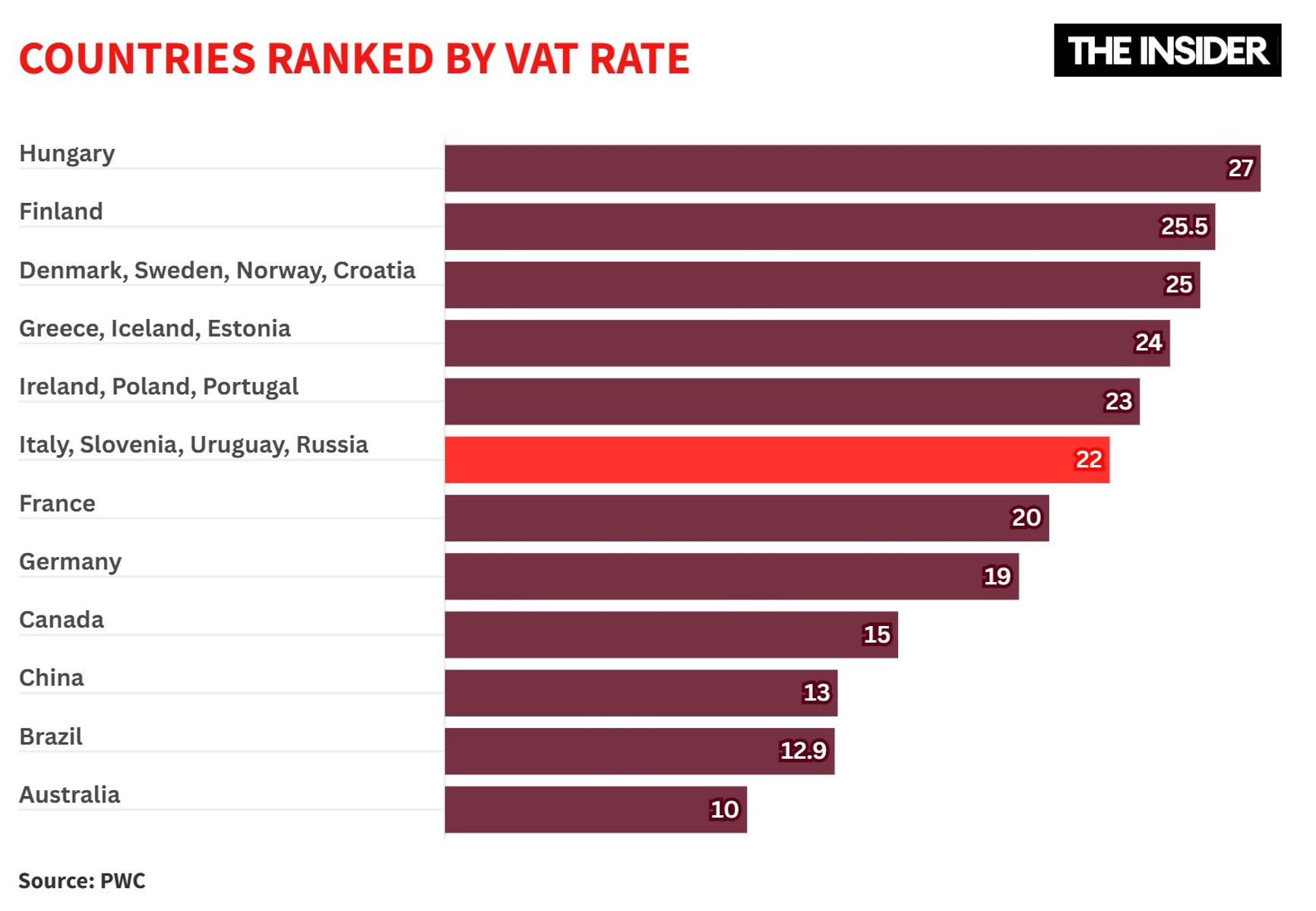

In pursuit of these aims, the standard value-added tax (VAT) rate is being raised from 20% to 22%. Among major economies, only Italy and Brazil extract revenues from businesses at such a rate. The increase puts Russia ahead of Spain and the Netherlands (where the tax rate is 21%), France, the UK, and Turkey (20%), and Germany (19%). Meanwhile, the United States has no VAT, while in Canada, rates vary by province but do not exceed 15%. In Japan, South Korea, and Australia, the VAT rate is 10%. In developing countries, VAT is generally lower than in Russia: 18% in India and Pakistan, 16% in Mexico, 15% in South Africa, 13% in China, and 12% in Indonesia.

Russia's new 22% rate will be the highest since the government of acting prime minister Yegor Gaidar in 1992, when it stood at 28% — only to be cut straight down to 20% a year later, and then to 18% in 2004.

An increase to 13.565 trillion rubles is planned for 2027, and in 2028 the figure is expected to reach 13.048 trillion rubles.

From January through August, spending was 21.1% higher than in the previous year. In 2024, it was 24% higher than in 2023. In 2023, the year-over-year increase was minimal — 3.9%, while in 2022 it jumped 26% over 2021. Even in the relatively peaceful year of 2021, federal spending rose 8.5% year over year.

Russia's military spending is planned at 46.1 trillion rubles in 2027 and 49.4 trillion rubles in 2028.

Meanwhile, the federal component was boosted from 3% to 8%.

Russia's new 22% VAT rate will be the highest since the Gaidar government in 1992

Additionally, companies with revenues higher than 10 million rubles ($120,494) will now be required to pay VAT. Pushing the threshold down from 60 million rubles ($722,964) will deliver a massive blow to Russian small and medium-sized businesses. A typical victim of the new move to expand the VAT taxpayer base is a small restaurant somewhere other than Moscow with an average bill of 1,000 rubles ($12) and roughly four bills per seat daily.

An increase to 13.565 trillion rubles is planned for 2027, and in 2028 the figure is expected to reach 13.048 trillion rubles.

From January through August, spending was 21.1% higher than in the previous year. In 2024, it was 24% higher than in 2023. In 2023, the year-over-year increase was minimal — 3.9%, while in 2022 it jumped 26% over 2021. Even in the relatively peaceful year of 2021, federal spending rose 8.5% year over year.

Russia's military spending is planned at 46.1 trillion rubles in 2027 and 49.4 trillion rubles in 2028.

Meanwhile, the federal component was boosted from 3% to 8%.

Previously, only establishments with 42 seats or more had to pay VAT, whereas now the threshold will be just seven seats. Aside from additional tax payments, this entails accounting expenses, since reporting also becomes significantly more complex.

Overall, the tax reform is anticipated to bring the budget close to 1.8 trillion additional rubles ($21.7 billion), of which the VAT hike will generate 1.2 trillion ($14.5 billion), while the lowered VAT threshold (the one that hits SMEs) will yield only 200 billion rubles ($2.4 billion). Another 74 billion rubles ($891.7 billion) is expected from bookmakers, whose contributions have been raised, and 66 billion rubles ($795.3 billion) from higher excise taxes on alcohol and tobacco.

Lies as state policy: the parable of not raising taxes

The increase of Russia’s main tax — along with the expansion of the taxpayer base — is an unscheduled measure. Moreover, during the 2024 election campaign, Putin specifically declared that nothing of the sort would transpire. Later on, the Finance Ministry repeatedly and firmly denied the possibility that taxes would be raised.

At the 2025 St. Petersburg International Economic Forum, Finance Minister Anton Siluanov said:

“In these conditions, we are indeed facing a perfect storm. The budget is also going through serious turbulence. Nevertheless, we discussed the issue of taxes last year and agreed not to touch the basic taxes — and that is the right decision. Because this too is a tool to keep our policy predictable.”

He had made similar promises before — on Oct. 16, 2023, in the State Duma, ahead of the increase in personal income tax:

“When drafting the three-year budget, we did not plan to touch the basic taxes, including personal income tax… We believe we could revisit the issue later. When? Perhaps in the next budget cycle. But now, as we are preparing the upcoming three-year budget, we have decided not to change the basic taxes.”

However, in February–March 2024 — in the run-up to the presidential “vote” — Putin publicly proposed higher taxes on the wealthy. And indeed starting Jan. 1, 2025, personal income tax shifted from a two-tier to a five-tier scale, with the top rate rising from 15% to 22%.

Also starting in 2025, the corporate profit tax was raised from 20% to 25% — and all of this increase went to the federal budget, not to the regions, upping federal revenue from the profit tax in 2025 by an astounding 78% — from January to July of this year, 2.26 trillion rubles ($27.2 billion) were collected compared to 1.27 trillion rubles ($15.3 billion) in 2024. As such, the minister’s statements can already be interpreted as a signal of imminent tax hikes.

On top of that, the VAT change is becoming something of a New Year tradition: for the second year in a row, key tax rates will rise on Jan. 1. Taxpayers should now have clear expectations, making it difficult to catch them by surprise a third time.

Some might move their money abroad or into the shadow economy in advance, cancel expansion plans, or shut down their businesses. The authorities consistently underestimate such effects, which manifests in overly optimistic forecasts.

Alongside preparing the federal budget, the Ministry of Economic Development has also published a macroeconomic forecast for the next three years. This time, expectations are much more modest: in the baseline scenario, GDP is projected to grow by 1.3% in 2026, and in the conservative scenario, by just 0.8%. In both cases, investment in fixed capital is expected to decline. On the other hand, inflation is projected to remain well under control, with prices expected to rise by 6.8% in 2025 followed by annual inflation of 4% starting in 2026, fully in line with the Bank of Russia’s targets.

If these forecasts are compared with those made a year ago, it becomes clear that the government is slowly coming to terms with an unflattering reality. In the fall of 2024, it expected GDP to grow by 2.5% in 2025; now it projects only 1%. Retail turnover was supposed to increase by 6–7.6% in 2025; now the expectation is no more than 2.5%. The inflation forecast, on the other hand, has moved in the opposite direction: from 4.5% to 6.8%.

An increase to 13.565 trillion rubles is planned for 2027, and in 2028 the figure is expected to reach 13.048 trillion rubles.

From January through August, spending was 21.1% higher than in the previous year. In 2024, it was 24% higher than in 2023. In 2023, the year-over-year increase was minimal — 3.9%, while in 2022 it jumped 26% over 2021. Even in the relatively peaceful year of 2021, federal spending rose 8.5% year over year.

Russia's military spending is planned at 46.1 trillion rubles in 2027 and 49.4 trillion rubles in 2028.

Meanwhile, the federal component was boosted from 3% to 8%.

The revisions in the forecasts show that the government is gradually coming to terms with an unflattering economic reality

Such comparisons help reveal the real worth of today’s forecasts and plans. Russia's budget is even less predictable than GDP trends, and recent adjustments have all been for the worse. According to the original 2025 budget law, the deficit was supposed to amount to 0.5% of GDP, or 1.2 trillion rubles ($14.5 billion). But at the end of April, the amended law upped the deficit to 1.7% of GDP, or 3.8 trillion ($45.8 billion).

Recently, a new official target has been announced: 2.6% of GDP, or 5.7 trillion rubles ($68.7 billion), which corresponds to a fourfold growth of the deficit. In 2024, the original budget law set the deficit at 1.6 trillion rubles ($19.3 billion); after the spring revisions, it was expected to reach 2.12 trillion ($25.5 billion), the fall amendments raised it to 3.3 trillion ($39.8 billion), and the actual figure turned out to be 3.5 trillion rubles ($42.2 billion).

Fictitious reduction in defense spending

According to the draft, federal budget spending will amount to 44.1 trillion rubles ($531 billion) in 2026, effectively remaining at the level set by the 2025–2027 budget law (currently 44.022 trillion rubles). This is 1.25 trillion rubles more than in 2025. Spending will then continue to rise, but in reality, this amounts to a spending freeze, as the increase barely keeps pace with inflation.

If the forecast proves accurate, spending trends will change sharply.

How is the government planning to rein in public spending growth? Surprisingly, the sharpest reduction so far is projected under the “National Defense” category. This year, 13.5 trillion rubles ($163 billion) will be spent on the military, but next year the plan calls for only 12.9 trillion ($155 billion). After that, however, a slight increase is expected.

Despite this, the war remains the single largest spending item: 29% of the 2026 budget. Another 3.9 trillion rubles ($47.0 billion) will go to the related category of “National Security and Law Enforcement,” accounting for 9% of total spending. By comparison, only 7 trillion rubles ($84.3 billion) — 16% of total expenditures — are allocated for “Social Policy.”

However, not everyone believes such a reduction is realistic. Some expenditures could be recorded under 2025 as advance funding of next year’s state defense orders, notes economist Sergei Aleksashenko:

“Who would object to receiving budget funds ahead of time? So what if that means increasing the deficit and borrowing at the end of the year! Last December, the Central Bank trialled another scheme, lending the Finance Ministry a trillion rubles with the help of commercial banks.

As for the size of the budget deficit, what difference does it make whether it’s four or four and a half times as large as initially planned? What matters is that if this year ends in a complete failure — and it already has, with no way to fix it — the projected picture for next year will still look quite appealing!”

Some expenditures may be partially recorded under other budget categories, noted Andrei Yakovlev, an associate researcher at Harvard's Davis Center: “If you use the search function in the explanatory note to see how many times the word ‘defense’ appears, you’ll find that dozens of defense-related expenses are listed under different sections of the budget.” As Yakovlev adds: “I would view this entire situation as the government's attempt to create what is essentially a technical budget — one that smooths over the rough edges and creates the illusion of balance. At the same time, they’ve already exhausted all the reserves they could realistically draw upon.”

An increase to 13.565 trillion rubles is planned for 2027, and in 2028 the figure is expected to reach 13.048 trillion rubles.

From January through August, spending was 21.1% higher than in the previous year. In 2024, it was 24% higher than in 2023. In 2023, the year-over-year increase was minimal — 3.9%, while in 2022 it jumped 26% over 2021. Even in the relatively peaceful year of 2021, federal spending rose 8.5% year over year.

Russia's military spending is planned at 46.1 trillion rubles in 2027 and 49.4 trillion rubles in 2028.

Meanwhile, the federal component was boosted from 3% to 8%.

A large share of defense-related spending is embedded in other sections of the budget

Indeed, spending on arms procurement can be found, for example, in the emergency response program — “procurement and repair of weapons, military and special equipment, production and technical goods, and property under the state defense order” — totaling 24 billion rubles ($289.2 million) in 2026. Overall, this program allocates 220 billion rubles ($2.7 billion) “to ensure the functioning of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, national security and law enforcement agencies, troops, and other military formations.”

On the other hand, Russia could continue waging war without increasing spending — like it did in 2023 when its army was suffering from ammunition shortages amid an effort to repel Ukraine’s counteroffensive.

Living on borrowed time

By constantly raising tax rates, the Kremlin is acknowledging that natural economic growth can no longer satisfy the state’s appetite. Despite warnings of an imminent or already unfolding recession from loyal experts and officials (including Economic Development Minister Maxim Reshetnikov), Putin’s government is trying to carve out an ever-larger share of a slowly shrinking pie.

However, when commenting on the 2026 budget, Reshetnikov no longer warns of a recession. According to the minister, the tax increases are “a prerequisite for further slowing inflation, ensuring macroeconomic stability, enabling a softer monetary policy, and ultimately supporting economic growth.”

Without tax raises, the budget deficit will grow even larger — an inflationary factor that would prevent the Central Bank from cutting its key rate, he explained. “That would lead to a prolonged period of tight monetary conditions and, consequently, significantly lower economic growth rates throughout the entire forecast horizon.”

In other words, according to Reshetnikov, higher rates mean higher tax revenues, a smaller deficit, lower inflation, looser monetary policy, and, ultimately, faster economic growth. The problem is that excessive tax hikes can eventually reduce total revenue by slowing the economy and driving businesses into the shadow sector. Were it not so, filling the budget would be an easy task.

Of course, the connection between budget deficits and inflation is often weak (or nonexistent) in the short and even medium term. Many developed countries have run much larger deficits than Russia for years while maintaining lower inflation. And monetary policy does not have to be eased simply because inflation has declined — the Bank of Russia already tried such easing from April 2022 to July 2023, only to find itself forced to tighten once again.

An increase to 13.565 trillion rubles is planned for 2027, and in 2028 the figure is expected to reach 13.048 trillion rubles.

From January through August, spending was 21.1% higher than in the previous year. In 2024, it was 24% higher than in 2023. In 2023, the year-over-year increase was minimal — 3.9%, while in 2022 it jumped 26% over 2021. Even in the relatively peaceful year of 2021, federal spending rose 8.5% year over year.

Russia's military spending is planned at 46.1 trillion rubles in 2027 and 49.4 trillion rubles in 2028.

Meanwhile, the federal component was boosted from 3% to 8%.

If tax hikes always boosted budget revenues without side effects, filling the state coffers would be an easy job

And then, monetary easing stimulates growth only in the short term — if at all. If that were not the case, countries would enjoy an endless supply of cheap money from their central banks and would never suffer from stagnation.

Concretely, in the Russian case, the government is ignoring a far more reliable and straightforward principle: increasing the tax burden harms economic growth, undermining incentives for productivity and thrift. The classic rule still applies: low taxes are a key driver of a nation’s long-term prosperity, while excessively high ones lead to stagnation and, sometimes, decline.

High taxes are a luxury affordable only to prosperous economies. By raising taxes in an economy that is already stagnating, the government is pushing it even deeper into recession — for the sole purpose of collecting more short-term money for the war. Doing so barely a year after raising profit and income taxes means destroying the tax base — or, as the saying goes, sawing off the tree branch that you’re sitting on.

An increase to 13.565 trillion rubles is planned for 2027, and in 2028 the figure is expected to reach 13.048 trillion rubles.

From January through August, spending was 21.1% higher than in the previous year. In 2024, it was 24% higher than in 2023. In 2023, the year-over-year increase was minimal — 3.9%, while in 2022 it jumped 26% over 2021. Even in the relatively peaceful year of 2021, federal spending rose 8.5% year over year.

Russia's military spending is planned at 46.1 trillion rubles in 2027 and 49.4 trillion rubles in 2028.

Meanwhile, the federal component was boosted from 3% to 8%.