Hush Naidoo Jade, Unsplash

Hush Naidoo Jade, Unsplash

Potato prices in Russia have stabilized, and officials are reporting the end of the “potato crisis.” Yet the tuber has yet to become affordable again, and it likely won’t anytime soon. The 2025 price surge had deep-rooted causes that have not been resolved: shrinking acreage, storage issues, widespread pest infestations, and the rising costs of fuel, fertilizers, seeds, and labor. Russians are already being forced to replace potatoes with cheaper carbohydrates, and despite official promises, the situation is only expected to worsen.

Prices grew, but potatoes didn’t

What makes potatoes so expensive?

Rising costs: fuel, fertilizer, seeds, and wages

Why imports didn’t help

What comes next

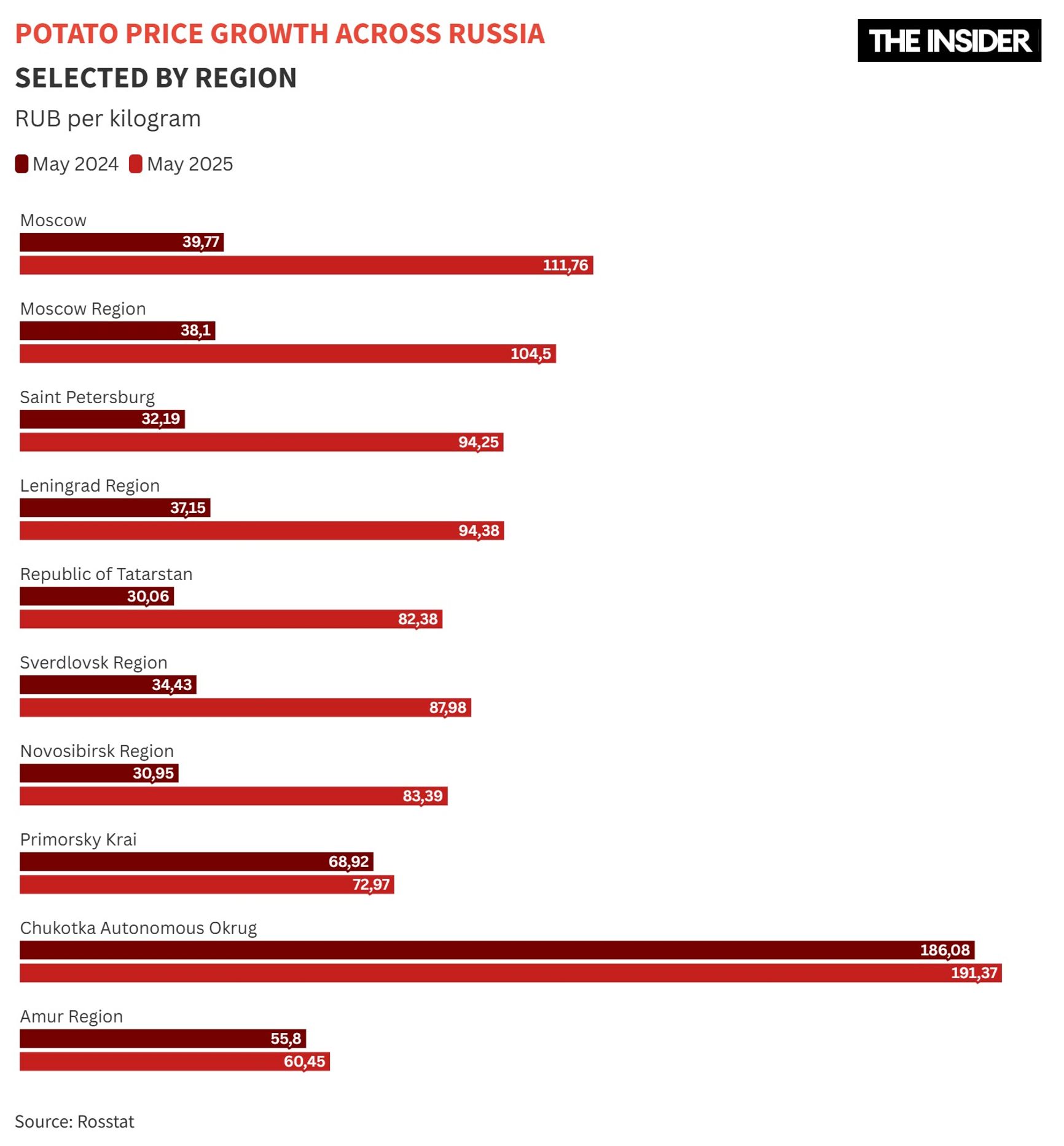

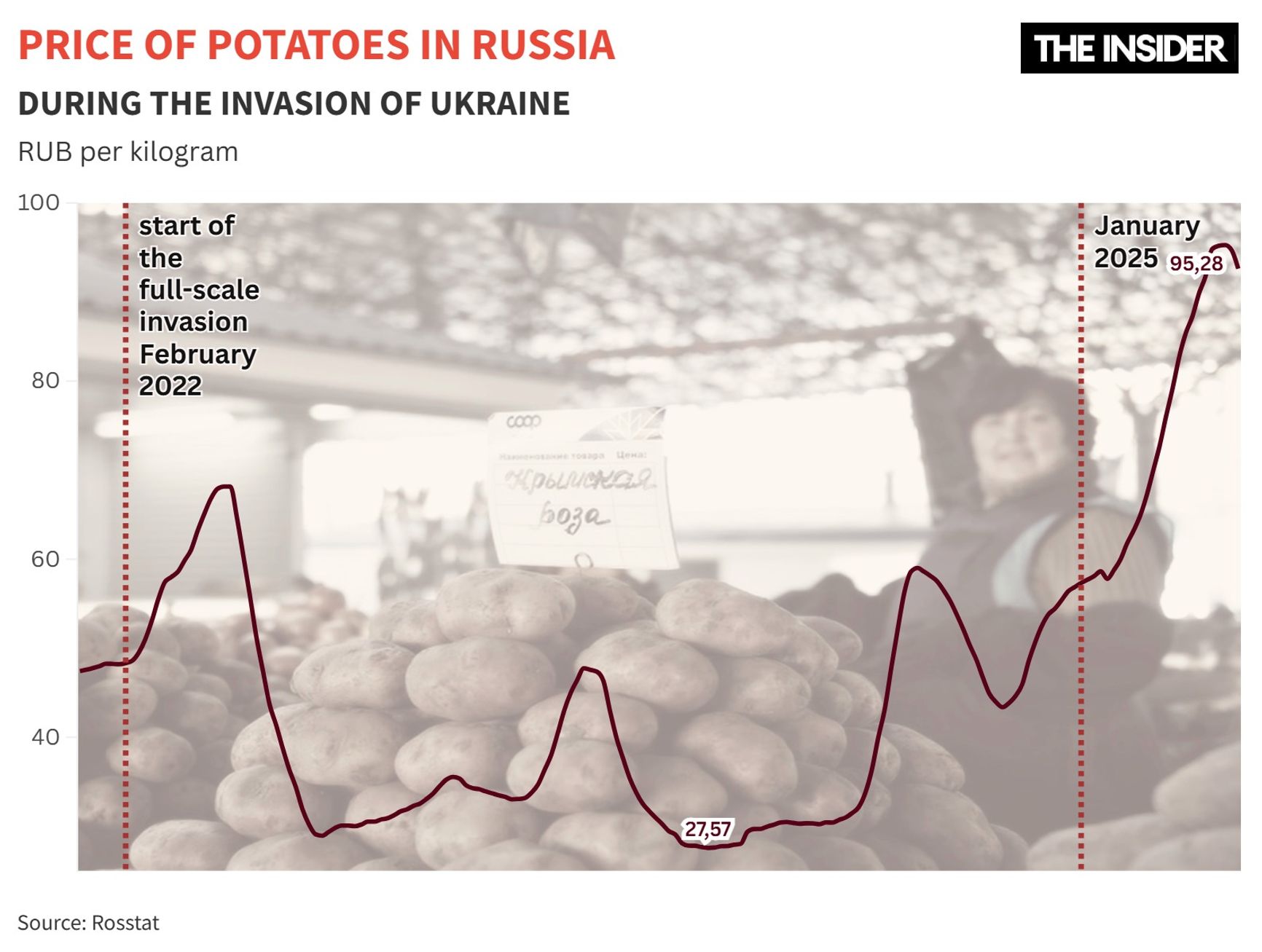

The average retail price of potatoes in Russia is now 92 rubles ($1.17) per kilogram — up from 56 rubles in June 2024. Wholesale prices rose even more rapidly — by 88% year-on-year.

No region escaped the price surge, though the pace of growth varied widely. According to Rosstat, a kilogram of potatoes in Moscow now costs an average of 112 rubles — nearly triple the price from a year earlier (May to May). In St. Petersburg, the price is 94 rubles, also close to a threefold increase. The most expensive potatoes are in the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, where they cost 191 rubles per kilo; however, prices there rose by only 3%. The cheapest are in the Amur Region — up by just 8%, to 60 rubles per kilo. These are average figures across varieties and retailers, but in reality, shoppers often see far higher prices on store shelves. Even at downmarket Magnit grocery stores in Moscow, potatoes were selling for 130–140 rubles per kilo as recently as May.

The unusual price surge was discussed both in the Kremlin and at last month’s St. Petersburg International Economic Forum. According to Agriculture Minister Oksana Lut, the crisis is over and potato prices in Russia have begun to decline, with a more noticeable drop expected to be seen in July. Lut attributed the earlier price hike to seasonal factors (the old harvest runs out in spring before the new one comes in) and a 2024 crop that was smaller than that of 2023 (down by 1.3 million tons).

“In 2023, we had a record potato harvest. This essentially caused prices to collapse, and producers were forced to sell their crops below cost. Against that low base, we’re now seeing a sharp increase in prices. That said, last year’s harvest was actually quite decent — on par with the five-year average. Potatoes were available in stores throughout the season. There were no shortages, and prices only caught up with 10 years of accumulated inflation in March. I believe the public panic over this issue also played a role,” Lut said.

But despite the strong 2023 harvest, potato prices also rose sharply last spring — by 88% between January and June 2024. That surge was driven by the same seasonal pattern seen in 2024, and was also exacerbated by a drop in imports, as Egypt, Russia’s main foreign supplier, redirected its exports to Europe.

The 2025 price spike had different causes, and they reflect deep structural issues in the sector — meaning a repeat of the potato crisis is all but inevitable.

In 2024, Russia harvested 17.8 million tons of potatoes — 12% less than in 2023. Most of this crop was grown by households on private plots (10.5 million tons), where yields also declined significantly — by 1.1 million tons. However, this segment rarely supplies the retail market, as such potatoes are usually consumed by the growers themselves or else sold informally.

What directly affects market prices is the so-called commercial harvest. Agricultural enterprises reduced output by 0.9 million tons, down to 4.3 million, while farmers and sole proprietors cut production by 0.4 million tons, to 2.951 million. This decline was the result of a reduction in the land area planted with potatoes — from 313,700 hectares in 2023 to 281,300 in 2024.

That drop in acreage is partly a consequence of the record-breaking 2023 season, when agricultural producers brought in 8.6 million tons — the highest figure in the past three decades. The resulting price collapse dealt a blow to the sector’s profitability, prompting a 4.2% cut in planted area, according to Rosstat. In commercial farming specifically, the reduction was even steeper — 11%, according to the AB-Center.

Another factor behind the shrinking potato acreage is the ongoing war in Ukraine, which is increasingly affecting Russian territory. Bryansk Region, the country’s leading potato producer, has taken farmland near the Russian-Ukrainian border out of use. As a result, the area planted with potatoes there fell by 4% in 2024.

One reason for the shrinking acreage is the ongoing war in Ukraine, which is increasingly affecting Russian territory

As a result, Russia’s self-sufficiency in potatoes in 2024 fell to 91.6% — well below the 95% benchmark set by the country’s food security doctrine.

Farmers see little incentive in growing potatoes. The crop requires substantial manual labor, and profit margins are highly unpredictable. Weather-related risks also play a major role. Last year, farmers faced rain, frosts, and flooding in the Urals and Siberia, followed by extreme heat in the summer. The planted area for potatoes in 2025 is slightly larger than it was in 2024, but it is still well below 2023 levels.

Even where potatoes are harvested, preserving them often presents a challenge. Losses during storage account for 15% of the crop from agricultural producers — about 1.2 million tons in 2024. Storage facilities are in short supply, and those that do exist are often substandard.

In addition, potatoes lose their quality when infested by pests, the most common of which is the stem nematode. This microscopic worm, despite its name, lives on the roots of potatoes and other vegetables, gradually weakening the plants and stunting their growth. The nematode isn’t harmful to humans; however, infected potatoes spoil quickly, and if peelings containing the parasite end up in the soil, it can damage the following year’s crop.

The greater danger is that if the parasite has been present in a potato field for several years, that land can become unsuitable for growing vegetables for years to come. Between 10% and 30% of potato fields in Russia are infested with stem nematodes.

Another widespread pest is the golden potato cyst nematode, which now affects up to 1 million hectares. Yields on infected fields can drop by as much as 50%.

“Many plots are infected with nematodes. And farmers keep planting potatoes on the same land. What is a nematode? It’s when the potato may grow large, but you can’t store it. By the time it reaches Moscow, it’s already gone soft, with a smell and everything,” says Nikolai Yuzefov, head of a potato farm. He notes that seeds brought into Central Russia via Belarus are often already contaminated.

Russia remains heavily dependent on imported seeds for potatoes, sugar beets, sunflowers, soybeans, and corn, according to the Central Bank. Citing data from Rosselkhoznadzor, the regulator notes that seed imports dropped 2.5 times in 2024, but at the same time, domestic seeds accounted for only about 68% of the Russian market last year. “Farmers are trying to switch to domestic seed stock, partly because of lower prices,” Central Bank analysts say.

Still, only 16% of potato fields will be planted with Russian seeds in 2025, according to a recent report by the Russian Grain Union. That will actually represent a “significant increase” after a disastrous 2024, when the share stood at just 2.2%.

The problem is not only with potatoes. Prices for fruits, berries, and vegetables are rising due to the increasing cost of fertilizers, fuel, and storage, the Ministry of Agriculture of Krasnodar Krai explains. These cost increases are a direct consequence of Western sanctions and of the ruble’s depreciation in 2024, officials say. Fuel has driven up expenses not only for planting and harvesting, but also for transporting the crops to consumers.

Prices for fruits, berries, and vegetables are rising due to the growing costs of fertilizer, fuel, and storage — direct consequences of Western sanctions and of the ruble’s depreciation in 2024

The wage race has also hit the agricultural sector, which now has to compete for workers with other industries. Former Agriculture Minister Alexander Tkachyov has warned of an impending crisis in farming due to a labor shortage. Rather than working the land, migrant laborers, he says, are becoming couriers — “you can’t lure them into the fields anymore.”

Igor Mukhanin, president of the Russian Gardeners Association, lamented that: “I’ve got decent conditions, meals, and buses for workers. But the Druzhba oil pipeline runs nearby. We had a good mechanic. Then someone came and asked how much we were paying him — 70,000 rubles ($887). They offered him 140,000 ($1,774). Soon there’ll be no one left to work in agriculture.”

Retail markups and intermediary companies have also had a major impact on the final price. Grocery store chains claim their average markup is only 22%, but according to Rusprodsoyuz, it exceeds 100%. According to potato farmer Yuzefov:

“The new Ministry of Agriculture is asking dumb questions behind closed doors: why did potatoes get more expensive? That’s not a question for us! Even in 2024, when I was selling at 35 rubles per kilo, why were they going for 90 in stores? That’s triple the price! For 35 rubles, our team of 250 people busts their backs in the fields, working day and night in heat and dust. Meanwhile, the bosses sitting in comfy chairs — at markets, bazaars, or wherever — let them explain why the price hits 90 rubles in stores. Just imagine how much they’re adding on and how much they’re stealing.”

Despite all the challenges, the government has decided to cut support for potato producers. In 2024, 4.2 billion rubles ($53.22 million) was spent on aiding vegetable production of all types. In 2025, the federal budget plans to allocate 3.7 billion rubles ($46.88), aimed primarily at investment projects.

Even accessing the allocated funds isn't always easy. Producers in the Bryansk Region had to turn to the Potato Union for help with obtaining subsidies. Meanwhile, potato farming demands serious investment. For wheat, costs per hectare are around 20,000 rubles ($253), but for a good potato harvest, at least 140,000 rubles ($1774) per hectare must be budgeted.

To support domestic producers, the government has imposed quotas on imported seeds from “unfriendly countries” — 16,000 tons in 2025. Nevertheless, last year only 770 tons of seeds were imported, a 93% drop according to Rosselkhoznadzor.

Efforts to ramp up imports were hampered by import tariffs — so much so that the Agriculture Ministry had to raise the duty-free import quota from 150,000 to 300,000 tons. Despite the restrictions, potato imports to Russia nearly tripled, reaching 432,200 tons.

One might have expected help from neighboring Belarus. At a meeting of the supervisory board of the Russian Land of Opportunity platform in late May, Vladimir Putin even appealed to Alexander Lukashenko on the matter. “Yesterday I met with representatives from various sectors, including agriculture, and it turns out there’s a potato shortage! I spoke with Alexander Grigoryevich Lukashenko, and he said: ‘We’ve already sold everything to Russia.’”

Lukashenko explained that the shortage had been exacerbated by speculation inside Belarus itself. As a result, despite being Russia’s main supplier of potatoes last year, Belarus cut its year-on-year exports by half in the first five months of 2025.

Russia does have other suppliers among neighboring countries — but they’ve run into issues too. Kazakhstan, for example, restricted potato exports to all countries except members of the Eurasian Economic Union (which includes Russia) after its potato exports rose by 150% in 2024. Still, the total volume shipped to Russia last year was a negligible 4,400 tons.

As a result, Egypt emerged as the main emergency supplier, sending 338,000 tons — two-thirds of all current imports (548,000 tons). And the African-grown vegetable isn’t cheap, selling for 90–120 rubles per kilo. Imports from China also skyrocketed — up from 4,000 tons in 2023 to 80,500 in 2024. Russia has increased purchases from other countries and even found new partners such as Georgia, which delivered 30,400 tons.

A source with knowledge of the situation — an economist who spoke to The Insider on condition of anonymity — says that potato prices may decrease in the fall, albeit temporarily. The arrival of the new harvest will help, and the authorities may also intervene in order to regulate prices, artificially bringing them down to between 60 and 100 rubles per kilogram.

But such a move, warns another analyst, is likely to create a new problem: producers and resellers could start supplying supermarkets — where prices will be under official control — with cheap, low-quality, or even spoiled potatoes. In the end, officials will be able to report that stores have reduced and maintained prices for domestic potatoes, while right next to rotting Russian produce will be perfectly washed imported alternatives selling for 200 rubles per kilo. Meanwhile, high-quality Russian potatoes — priced at up to 150 rubles per kilo — will end up at open-air markets and wholesale vegetable depots, which are less closely monitored by regulators. In other words, the situation will change only on paper, not in practice.

Other analysts interviewed by The Insider agree: due to Western sanctions, the closure of agricultural enterprises, the outflow of workers amid the war in Ukraine, and ongoing problems with seeds and fertilizers, food prices will continue to grow annually by 20–30%. One of them stresses the reality that the price increases are hitting people hard:

“Food prices are rising, and the cost indexes for borscht and shawarma will continue to increase. Meanwhile, sales in the premium segment remain stable. Wealthier consumers continue to buy what they want. However, others are shifting from quality, nutritious products to cheaper carbohydrates. Supermarkets are already observing middle-income shoppers moving into the low-cost segment — that is, toward bread, grains, and processed foods.”

He believes the situation will only deteriorate further. New production technologies are not arriving due to sanctions, and the government is actively printing money while potentially attempting to regulate prices. All these factors are driving inflation, which could be further fueled by additional sanctions.

“Therefore, we expect a surge in food prices in August, September, and October. While food riots are unlikely — substitutes can keep people fed — the consequences for demographics and public health are yet to come,” he concludes. Meanwhile, according to data from the Institute for Economic Forecasting of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Russians are indeed already replacing the potatoes in their diets with bread, pasta, and cereals.

К сожалению, браузер, которым вы пользуйтесь, устарел и не позволяет корректно отображать сайт. Пожалуйста, установите любой из современных браузеров, например:

Google Chrome Firefox Safari