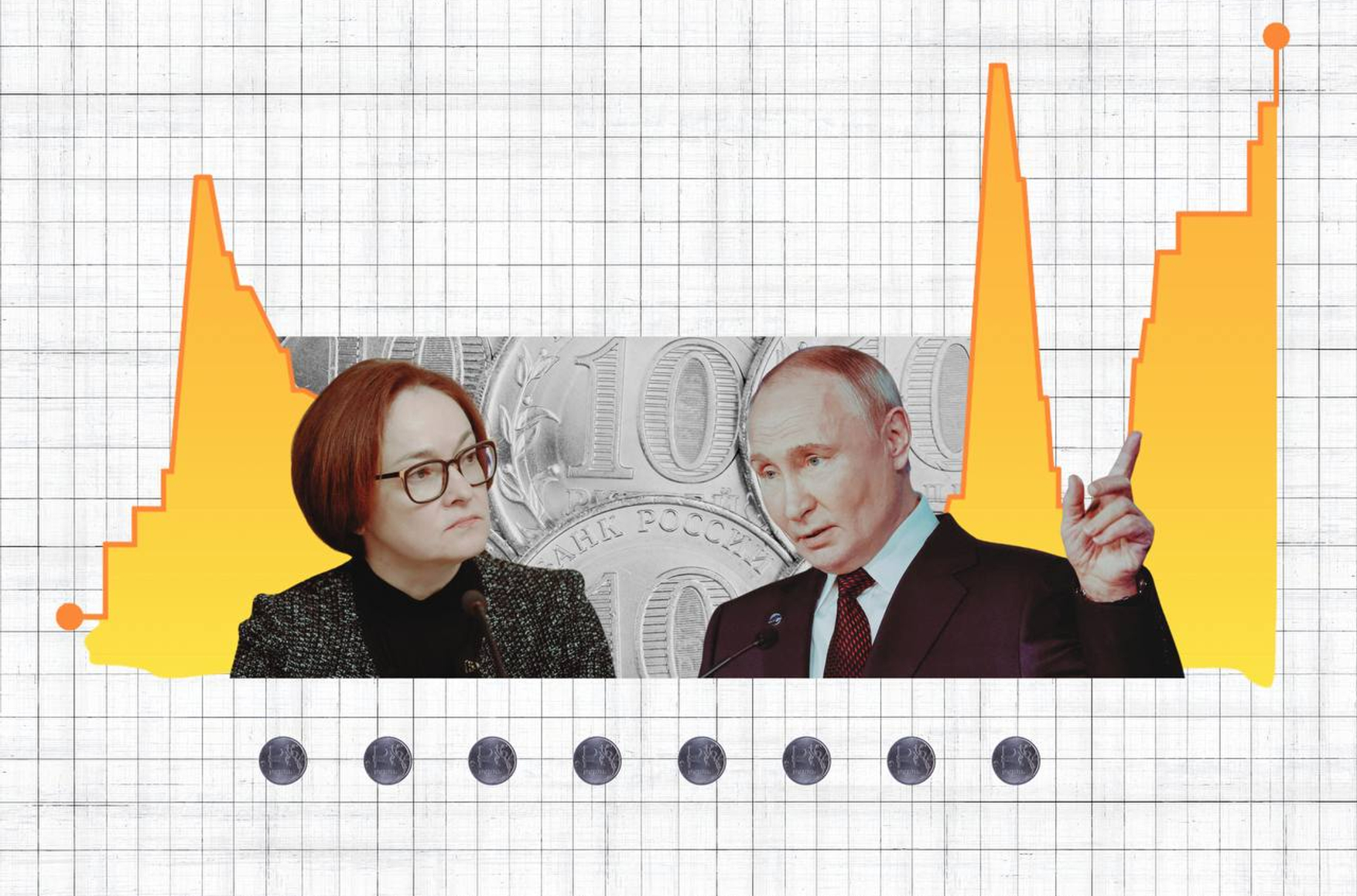

The Bank of Russia has left its key interest rate unchanged, contrary to predictions of further raises. The day prior, Vladimir Putin had asked the Central Bank to make a “balanced” decision. Still, Russia's key rate remains at a record high, affecting the country’s economic growth prospects and putting it in the same monetary policy league as Iran, Sierra Leone, and Angola. This decision also increases the risk that financial authorities will lose their independence from government influence, as has happened in Turkey and Venezuela.

Content

Why upping the rate doesn't work

All countries are unhappy in their own way

Uncertainty off the charts

The Bank of Russia did not raise the key rate on Dec. 20, leaving it at 21%. “There has been a more substantial tightening of monetary conditions,” bank officials explain. Since the October increase, loans and deposits have grown in price “significantly more than the October key rate hike implied.” The high cost of loans has worried the population so much that the issue was raised during Vladimir Putin's phone-in interview on the eve of the meeting. Putin expressed hope that the decision of the Central Bank's board of directors “will be balanced and will meet the requirements of today.”

However, will a tight monetary policy rein in inflation? And what risks does it create for the Russian economy? There is a whole club of high key rate countries, and although their economic experience varies, the result is hardly ever positive.

The 21% key rate of the Bank of Russia stands at its highest level in modern history. The Central Bank set this record in October and maintained it in December. Many Russians remember the exorbitant rates of the 1990s, which reached 100% and even 200%. But those figures were associated with nationwide economic reform, hyperinflation, and the conflicting interests of key economic actors. One could say that the key rate at that time was a very different instrument and had much less impact on the economy.

Turkey set a world record around the same time, jacking up its rate to 355% in April 1994. With a current rate of 50%, Turkey today stands second only to Venezuela’s 59.23%. The vast majority of high-rate economies demonstrate poor overall performance.

Why upping the rate doesn't work

The key rate determines the cost of money for banks and is therefore considered one of the main mechanisms for regulating the economy through inflation management. Increases in the Central Bank rate set off a chain reaction — higher interbank lending rates lead to higher rates on loans, deposits, and bonds, making businesses and households less willing to borrow and consume but more willing to save.

The Central Bank issues a loan to a commercial bank (Sber, VTB, and others with a state-owned stake). The bank invests in federal bonds, essentially transferring the money to the Ministry of Finance, and then transfers it as collateral to the Central Bank again, receives a new loan against it, and does not repay it, placing the federal loans in the ownership of the Central Bank. This way, money from the Central Bank goes directly to the budget. At the same time, federal bonds are among the assets of the Central Bank, and the Ministry of Finance accrues coupon income on them in accordance with the current market rate. Central Bank receives income, increasing its profit, but returns 75% to the budget according to the law. Thus the Ministry of Finance gets its money back, paying only 25% of the average market rate for servicing this debt. The process is referred to as monetary easing.

In Russia, it corresponds to the minimum interest rate at the Bank of Russia's mandatory repurchase (repo) auctions for a week and the maximum interest rate at the Bank of Russia's deposit auctions with the same term.

The least developed countries are characterized not only by a high level of extreme poverty but also by a structural weakness in economic, institutional, and human resources. The list of LDCs is maintained by the UN General Assembly and currently includes 46 countries.

The highest key interest rate in Russia’s history was 210%, in effect from Oct. 15, 1993, to Apr. 28, 1994.

A high key rate makes loans more expensive and raises deposit rates, so businesses are less likely to invest in production, and the population chooses to save money in banks rather than consume. In theory, these trends should reduce inflation. In reality though, the effect takes some time to make itself felt. Russia's Central Bank, for example, has calculated that the impact of a rate hike is typically observed only after two or three quarters. Additionally, a key rate raise has a non-linear effect on inflation. In part, this can be explained by the downside of high rates: they put a brake on the economy. High-interest business loans hamper production development, causing a slump in tax revenues and a budget deficit.

Finally, the third and most important factor is that the key rate helps regulate the ratio of investment and consumption in a normal market economy, but this mechanism does not work in Russia's military dictatorship. The Russian economy was not a fully market economy even before the full-scale invasion, with the share of state-owned companies exceeding 50%. In recent years, the country has also seen rapid growth in the defense industry, and the Kremlin's military spending will not be affected by any interest rate. At the same time, economic uncertainty affects both consumers and private businesses, who are in no hurry to invest. In such a setting, rising interest rates cause a slower decline in spending than the textbook suggests.

The Central Bank's actions in October have put Russia's economy on the verge of stagflation — a combination of anemic growth (or even recession) and rapidly rising prices. Experts from the Moscow-based Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short-Term Forecasting (TsMAKP) have already hinted at the prospect of stagflation, without explicitly mentioning the self-inflicted causes of Russia’s economic malaise: the war and sanctions. Under the circumstances, Russia will not be able to solve its problems Reagan-style — by orchestrating a powerful inflow of foreign capital to make up for the decline in “domestic” investment — as international isolation has shortened Moscow’s list of options. Rather, the tight anti-inflationary monetary policy could trigger an economic shock, followed by a decline in production — a scenario similar to what happened in Italy (1981-1983), Israel (1984-1987), and Mexico (2000-2002).

All countries are unhappy in their own way

Since Turkey holds modern history’s ignominious record when it comes to key rate hikes, the question about the effectiveness of the Bank of Russia's actions is more and more often phrased as “whether Russia risks repeating the Turkish scenario.” For two years after the pandemic, Turkey pursued “Erdoganomics.” The authorities tried to ramp up the economy by cutting interest rates, hoping to accelerate consumption despite a surge in inflation. As a result, inflation peaked at 85.5% in October 2022 while the key rate was held steady at 10.5% on President Erdogan's orders. He changed the strategy in June 2023 — after yet another re-election — and the Turkish Central Bank started to raise the rate: first to 15%, then to 25%, and finally to the current 50% in March 2024.

“The situation in Turkey is quite different from that in Russia,” economist Sergei Aleksashenko tells The Insider. “Turkey has no independent central bank. The authorities started with powerful lending to the economy, but now they have been tightening the screws for a year, and the situation is improving. Most importantly, to facilitate economic growth amid high inflation, the Bank of Turkey built up its foreign currency liabilities once its reserves ran out. And we have yet to see how Turkey will come out of this.”

The high key rate has not yet brought inflation under control, but it has lowered it from 85% to 49%. Meanwhile, Turkey's economic growth remains modest: the IMF forecasts an increase of 3.5% this year and another 2.7% next year.

The Central Bank issues a loan to a commercial bank (Sber, VTB, and others with a state-owned stake). The bank invests in federal bonds, essentially transferring the money to the Ministry of Finance, and then transfers it as collateral to the Central Bank again, receives a new loan against it, and does not repay it, placing the federal loans in the ownership of the Central Bank. This way, money from the Central Bank goes directly to the budget. At the same time, federal bonds are among the assets of the Central Bank, and the Ministry of Finance accrues coupon income on them in accordance with the current market rate. Central Bank receives income, increasing its profit, but returns 75% to the budget according to the law. Thus the Ministry of Finance gets its money back, paying only 25% of the average market rate for servicing this debt. The process is referred to as monetary easing.

In Russia, it corresponds to the minimum interest rate at the Bank of Russia's mandatory repurchase (repo) auctions for a week and the maximum interest rate at the Bank of Russia's deposit auctions with the same term.

The least developed countries are characterized not only by a high level of extreme poverty but also by a structural weakness in economic, institutional, and human resources. The list of LDCs is maintained by the UN General Assembly and currently includes 46 countries.

The highest key interest rate in Russia’s history was 210%, in effect from Oct. 15, 1993, to Apr. 28, 1994.

The situation in Turkey is quite different from that in Russia, and we have yet to see how Turkey resolves it

Another high-rate country is Venezuela, which — like Russia — is under U.S. oil sanctions. Bank of Venezuela statistics estimated an inflation rate of 40,394% in 2018, but in recent years international analysis of price growth has registered it at anywhere from hundreds of thousands to more than a million percent. According to an official Bank of Venezuela report released in October 2024, annualized inflation amounted to only 4%.

The third country in the high-rate club, Argentina, is rising from the ashes as we speak. Dec. 10 marked one year since new President Javier Milei took office, and his tenure has been marked by a wide range of drastic measures taken to reform an economy where inflation last dipped below 50% back during the COVID-19 pandemic. Milei lowered the key rate from 126% at the beginning of December 2023 to 100% in the second half of the month, and it has since been cut to 35%. The new president devalued the national currency from 366 to 800 pesos per $1. He also significantly reduced government spending — cutting energy and transportation subsidies, laying off more than 30,000 civil servants, and stopping the issuance of currency. His actions have increased tax revenues, optimized an excessive regulatory framework, and established control over the central bank's monetary policy.

As a result, annual inflation plunged from 211.4% when the new president took office to 166% in November 2024, and monthly inflation shrank tenfold to 2.4% in November. In the meantime, according to official statistics, Argentina's poverty rate reached a historic high in the first half of 2024, peaking at 52.9%. As recently as the end of 2023, it had been 41.7%. Experts from the Center for Argentine Political Economy (CEPA) also said that nearly one-fifth of the population, about 8.3 million people, cannot afford a basic basket of groceries. According to the IMF's October forecast, Argentina's economy will shrink by 3.5% this year, but it is expected to rebound with 5% growth in 2025.

The Central Bank issues a loan to a commercial bank (Sber, VTB, and others with a state-owned stake). The bank invests in federal bonds, essentially transferring the money to the Ministry of Finance, and then transfers it as collateral to the Central Bank again, receives a new loan against it, and does not repay it, placing the federal loans in the ownership of the Central Bank. This way, money from the Central Bank goes directly to the budget. At the same time, federal bonds are among the assets of the Central Bank, and the Ministry of Finance accrues coupon income on them in accordance with the current market rate. Central Bank receives income, increasing its profit, but returns 75% to the budget according to the law. Thus the Ministry of Finance gets its money back, paying only 25% of the average market rate for servicing this debt. The process is referred to as monetary easing.

In Russia, it corresponds to the minimum interest rate at the Bank of Russia's mandatory repurchase (repo) auctions for a week and the maximum interest rate at the Bank of Russia's deposit auctions with the same term.

The least developed countries are characterized not only by a high level of extreme poverty but also by a structural weakness in economic, institutional, and human resources. The list of LDCs is maintained by the UN General Assembly and currently includes 46 countries.

The highest key interest rate in Russia’s history was 210%, in effect from Oct. 15, 1993, to Apr. 28, 1994.

Argentina's new leader successfully fights inflation, but poverty is on the rise

The “high-rate club” cases vividly illustrate how many parameters factor into economic outcomes, but the level of a central bank's independence is certainly among the most important factors. If the regulator is not autonomous and can be swayed by populist slogans, its policies become inconsistent and often harmful, economists argue. Confidence in Turkey's central bank has been undermined by its ineffective monetary policy, in part due to political interference in decision-making, Moody's observes.

Uncertainty off the charts

Although Russia's situation is fundamentally different from that of Turkey, Venezuela, and Argentina, it faces both high interest rates and rampant inflation. Economist Vladislav Inozemtsev believes that inflation poses the greatest threat to business, state monopolies, and the population: “When inflation is predictable, albeit high, the economy can enjoy relative stability. However, it is very difficult to make predictions for the coming year because the accumulated level of inflation is sufficient to provoke drastic developments. I assume that inflation — even the official inflation rate — will go well over 10%. And it is unclear how the Central Bank will react.”

Inozemtsev points out that after its October rate hike, the Bank of Russia essentially used an additional instrument of lending to the budget by increasing the volume of repo transactions with federal bonds. “If this practice continues over longer periods, we can expect a sizable emission increase, which will further accelerate inflation,” Inozemtsev says.

The key rate is set to peak in the first quarter of 2025. It is expected to remain at an elevated level until the summer, and it will not dip below 20% until the end of 2025, according to Natalia Orlova, chief economist at Alfa Bank.

The Central Bank's high rate is “the hardest case” for the economy, Inozemtsev notes. Other economists surveyed by The Insider agree: not only commercial and consumer lending, but also large government construction projects depend on the key rate. Additionally, Russia’s state budget covers the difference between the market rate and the preferential rate on mortgage programs for families and IT professionals.

Even if we discard the scenario of its further sharp increase, Russia is already facing a slowdown in construction and will be losing billions of dollars from the budget annually in order to subsidize preferential rates on loans. These factors will additionally impede the country’s unimpressive economic progress. According to the OECD's December forecast, Russia's GDP growth in 2024 will amount to 3.9% (a slight improvement against the previously forecasted 3.7%) but will drop to just 1.1% in 2025.

The Central Bank issues a loan to a commercial bank (Sber, VTB, and others with a state-owned stake). The bank invests in federal bonds, essentially transferring the money to the Ministry of Finance, and then transfers it as collateral to the Central Bank again, receives a new loan against it, and does not repay it, placing the federal loans in the ownership of the Central Bank. This way, money from the Central Bank goes directly to the budget. At the same time, federal bonds are among the assets of the Central Bank, and the Ministry of Finance accrues coupon income on them in accordance with the current market rate. Central Bank receives income, increasing its profit, but returns 75% to the budget according to the law. Thus the Ministry of Finance gets its money back, paying only 25% of the average market rate for servicing this debt. The process is referred to as monetary easing.

In Russia, it corresponds to the minimum interest rate at the Bank of Russia's mandatory repurchase (repo) auctions for a week and the maximum interest rate at the Bank of Russia's deposit auctions with the same term.

The least developed countries are characterized not only by a high level of extreme poverty but also by a structural weakness in economic, institutional, and human resources. The list of LDCs is maintained by the UN General Assembly and currently includes 46 countries.

The highest key interest rate in Russia’s history was 210%, in effect from Oct. 15, 1993, to Apr. 28, 1994.