After Russia's attack on Ukraine, Europe did not give in to the Kremlin's blackmail and managed to turn away from Russian energy sources, albeit at a high cost. China and India have benefited from the redistribution of global energy supplies, but Turkey has arguably gained the most from the situation. Recep Erdoğan wants to make the country one of the most influential players in the global energy market, but he may face an unexpected rival – Cyprus, whose forthcoming presidential elections may decide the future of the great energy game.

Content

Winners and losers

Turkey: a future energy superpower?

Cyprus appears on the scene

Winners and losers

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the drastic changes on Europe’s energy map became evident by the end of 2022. Not only did the EU move to end its dependency on Russian oil and gas, but it also lobbied for a price ceiling on the raw materials that brought the price of Urals-grade oil down to an unprecedented 50% of its US counterpart Brent. Having banned Russian coal, oil and petroleum products (starting from February 5 this year), Europe has triggered a restructuring of the market, and multiple countries have both lost and gained from the process.

Judging from the results of the past year, the EU itself became the principal loser, having had to spend at least €500bn on the purchase of energy at extremely high prices and on subsidizing national consumers. Despite the cost, the Europeans managed to adapt to the new conditions and confidently coped with Putin's attempt to freeze the Old World. Many experts are now saying that the following winter will be even more difficult than the current one, but this is doubtful – at the very least, oil and gas prices in Europe will almost certainly not reach last year's record levels.

As for the winners, the picture here looks more varied. First of all, there's China, which can now unilaterally dictate the price of East Siberian coal and gas to Russia; China has also received and is receiving oil on preferential terms (in recent months the discounts reached $13 per barrel compared to fuel from Saudi Arabia). In the next few years, China has every chance of remaining the largest buyer of Russian energy resources, if all types are taken into account.

India, which purchased 33 times more Russian oil in December 2022 compared to a year ago and brought supplies from Russia to almost a quarter of its total imports, has also been a beneficiary of the Ukrainian conflict: average Urals prices throughout the year were $25-30/bbl lower than that of Brent. Indian refiners have also begun to produce petroleum products from Russian oil in preparation for delivery to Europe.

Turkey: a future energy superpower?

However, Turkey has arguably become the biggest beneficiary. Turkey has almost doubled its purchases of Russian oil, and became the largest importer of Russian gas by the end of last year and will surely keep that position this year. The demand for fuel transit through Turkish territory has increased because of the Russian-Kazakh tensions over the Caspian Pipeline Consortium; and finally, despite the difficult relations with Ankara, the Kremlin has actually risked offering President Erdogan a gas hub in Thrace to transport Russian fuel to Europe.

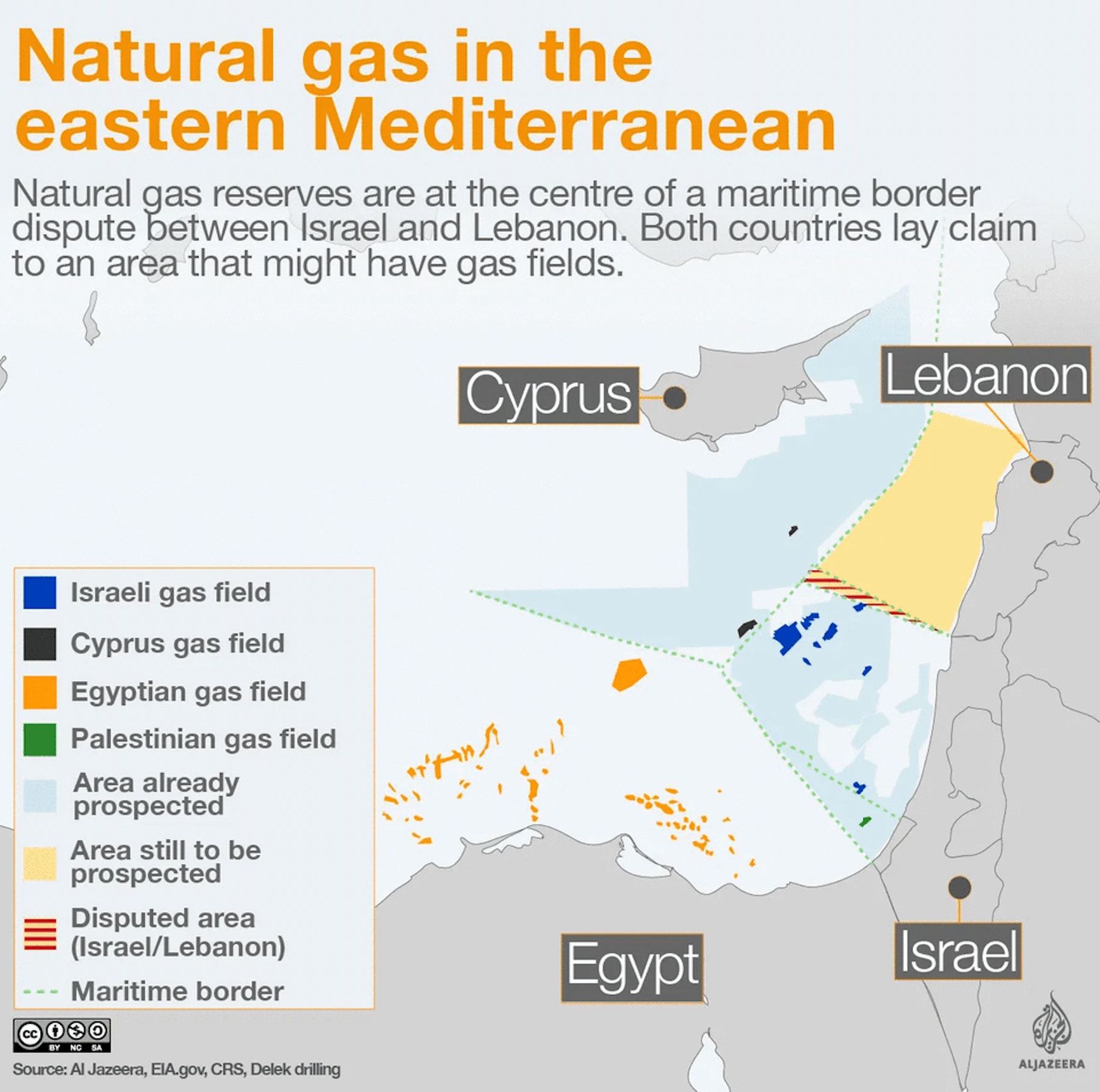

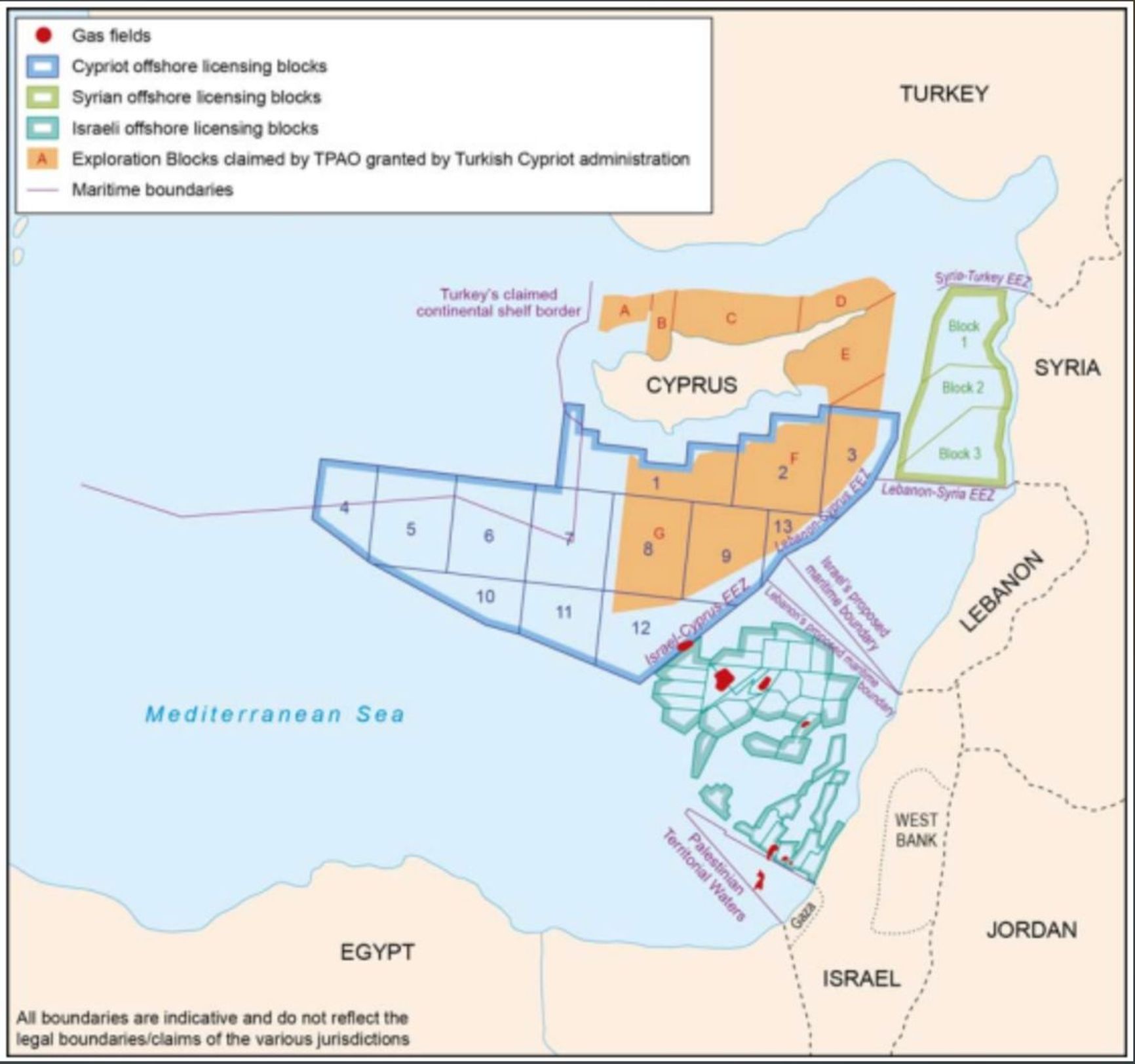

This could turn Turkey into a new energy superpower, and not just on a regional scale. President Erdoğan, in his aim to become the leader of the entire Sunni world, is very closely following the changes in the energy landscape in the Mediterranean: in recent years, Turkey has increased its proven gas reserves in the Black Sea and Mediterranean to 700 billion cubic meters and it is looking closely at the deposits in the territorial waters of Greece and Cyprus; it is beginning to restore diplomatic relations with Israel and Egypt, understanding the likely importance of these countries in the regional gas market (the volume of gas reserves in the Israeli and Egyptian offshore fields exceeds 3.2 trillion cubic meters).

Ideally, Erdoğan would dream of turning Turkey into a hub not only for Russian, Kazakh and Azerbaijani, but also for Middle Eastern oil and gas, which would essentially allow the country to replace Russia in the European gas market – if not in the regional energy market entirely. The Turkish authorities are taking tough measures to that end: one can recall the drilling attempts near Crete and Kastelorizon, the use of warships to evict the ENI and Total gas exploration expeditions from the territorial waters of Cyprus, and a series of other incidents that caused outcry in Europe.

Erdogan dreams of replacing Russia in the European gas market

The dividends Ankara has received from peaceful mediation in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, as well as the interest of major European powers in Turkey's consent to NATO enlargement, ensure – at least for now – a relatively high degree of Western tolerance for impromptu Turkish actions in the Mediterranean. Until recently, this situation was also supported by the position of Cyprus, where the experienced and reserved President Nicos Anastasiades sought to coexist with the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), a breakaway state recognized only by Ankara, and to continue the “peace process” under the auspices of the UN. However, the situation may change significantly in the near future.

Cyprus appears on the scene

Turkey's behavior is understandably irritating to Greece and the Republic of Cyprus, which cannot but be reflected in the mood of its voters. Cypriot society appears divided prior to the presidential election scheduled for February 5. Nicos Christodoulides, a foreign minister in the second Anastasiades government known for his anti-Turkish stance, is still leading in the polls, but is considered by many to be a “non-systemic” candidate, as the ruling Disy (Democratic Rally) party has not only refused to support his candidacy, but even expelled him from its ranks.

Turkey's behavior is understandably irritating to Greece and the Republic of Cyprus

Christodoulides’ nomination was supported by three small parties, with the politician positioning himself as an independent presidential hopeful – with a record 14 candidates registered so far in the race for the island nation’s presidency. The 2023 campaign, like many presidential races before it, is focused on the island's fragmentation, the sustainability of its financial system, and what many see as its over-reach into the global “offshore economy” – this year’s election, however, also has an important distinction.

Cyprus, until recently, has had little to do with the energy problems and tensions that have linked and divided Europe and the Greater Middle East. Gas exploration in the area began in the late 2000s; the first major gas-bearing area in the island's territorial waters (the Aphrodite field) was explored in 2011 and declared commercially attractive in 2015. Since then, several more discoveries have been made, which have brought the gas reserves in Cyprus' jurisdiction to an estimated 400-600 billion cubic meters. In comparison, Israel's estimated gas claims total 1 trillion cubic meters, while Turkey's reserves total over 700 billion. Notably, commercial deposits of Cypriot gas are located near the Israeli and Egyptian continental shelves.

Al Jazeera

Both countries already have established export channels to Europe, while much of the waters to the west and north of the island are contested by Turkey and the TRNC, causing significant problems. Almost half the areas considered most promising for exploration are still not delineated.

Immediately after the first discoveries, dozens of companies applied for further drilling permits in Cypriot waters – energy giants such as the French Total, Royal Dutch Shell, US-based Chevron (which received the rights to develop after the takeover of American Noble Energy, which first discovered gas on the Cypriot shelf), Italian ENI, South Korean Kogas, Qatar Petroleum and even Israeli Delek Group have already secured exploration rights in the country's waters.

Moreover, projects to connect the Israeli and Egyptian fields to Cyprus and then to Greece by underwater pipelines for further gas exports to Europe are in development, while the construction of the EuroAsia Electricity interconnector between Greece, Cyprus and Israel, financed by the European Commission, is already in full swing.

Not only (and not so much) is the unity of the island state at stake in this year's elections in Cyprus – the interests of the world's energy majors are also in play.

The interests of the world's energy giants are at stake in this year's elections in Cyprus

It is unlikely that there is a real opposition between the Turkish and Cypriot transit routes – as of today, the Turkish option has more interested parties and is potentially loaded with a much larger volume of gas. However, neither President Erdoğan nor Christodoulides, if elected (although the elections will face a difficult second round), will fail to accuse each other of an “energy war,” which will further exacerbate the already difficult situation in the region. (I should add that Ersin Tatar, the TRNC president elected two years ago, also does not seem like a dove, having already been involved in challenging the status of Varosha, formerly a famous resort and now an abandoned suburb of Famagusta, as set out in UN-brokered agreements).

Today, many in Cyprus are questioning whether the election of the undoubtedly popular but overly eccentric Christodoulides is in the interests of a country in such need of healthy relations with its neighbors. In Washington and Brussels, the attitude to the current leader of the race remains moderately cautious. Moscow and Ankara are even ready to welcome his victory, though for different reasons: Russia hopes for a possible deterioration of relations between Cyprus and the Western powers, which advocate continuing the “peace process”, while Turkey believes that the unwillingness of the Republic of Cyprus to compromise increases the chance of greater international recognition for Turkey.

It is too early to say how the elections in Cyprus will unfold, but one thing is clear: with the severance of energy ties between Russia and Europe, the focus of European energy policy will certainly shift to the south. Talks are already underway to buy gas from Israel and Egypt, and refineries in the Gulf are ramping up production of petroleum products in anticipation of the European embargo on Russian products that enters into force in early February. The Gulf states, the new players in the Eastern Mediterranean, and Turkey, backed by Russian, Azeri and Kazakh oil and gas, are Europe’s new partners in the big energy game, while the EU enters the playing field with the need to consider both the political preferences of its voters and the exalted nature of its elected politicians.