Last week, the Dossier Center published a long read on cocaine traffic to Russian via Moscow's embassy in Argentina. Its authors challenged the official findings of the investigation, which had exonerated Russian diplomats and officials. The Insider's investigation, which also takes note of both the Argentinian and the Russian case files, leaves no room for doubt: the Russian ambassador and other high-ranking diplomats were actively involved in cocaine trafficking, while Russian authorities impeded justice by ignoring evidence, hindering the investigation, and setting up cyberattacks.

Content

The official version: «A joint operation»

What actually happened in Argentina?

The Baron and the Kremlin

The official version: «A joint operation»

On February 22, 2018, Argentinian foreign minister Patricia Bullrich gave a press conference, sharing the details of a joint Russian-Argentinian investigation of a drug-trafficking gang that “used or attempted to use the Russian diplomatic pouch for smuggling”. Bullrich estimated the haul as 389 kilos of cocaine worth $50 mln (however, the batch's market wholesale value is closer to $11 mln).

According to the official narrative, Russian ambassador Viktor Koronelli contacted Bullrich late in the evening on December 13, 2016, and set up a meeting “accompanied by three FSB officers”. He disclosed his suspicions about a drug stash in the embassy. The Argentinian police somehow procured 389 kilos of flour in the middle of the night, replaced the discovered cocaine, and placed the suitcases used as containers under surveillance. The official version also asserts that a man called Ivan Blizniouk, an Argentinian police officer of Russian descent, attempted to move the suitcases. The other defendant is his accomplice Alexander Chikalo, president of Russian Orthodox Philanthropists of Latin America (this club, which has Blizniouk for vice president, presented the icon of Our Lady of Kazan to a Russian Orthodox diocese in Mar del Plata).

Shortly after the press conference, Germany extradited Russian national Andrey Kovalchuk (to whom Bullrich referred as “Señor K, traffic organizer”). For some reason, the Russian judicial proceedings regarding his pre-trial restrictions have taken place behind closed doors since November 2019. The only Russian embassy employee to be arrested has been logistics manager Ali Abyanov, who is also on trial in Russia. Besides, Russia assured Argentina that the embassy had fired Abyanov as early as on August 16, 2016. In this case, it remains unclear how he could have managed to move the cargo to the adjacent school building in December 2016 (as per the official narrative). Surprisingly, according to the case files (page 7 of the indictment in Case 17882/2016 of the Federal Prosecutor's Office of Argentina), S. Muravyov, deputy head of the FSB's drug control directorate, drew up the report on the suspicious suitcases as early as in October 2016. If this were true, why did the ambassador not report the cargo until a month and a half later?

The Argentinian case files suggest that Kovalchuk had at least one superior – Konstantin Loskutnikov (calling himself Baron von Bossner). He heads the aforementioned Russian Orthodox Philanthropists' Club in Berlin – an organization that the Russian investigators strangely overlooked, and the Argentinians checked for a formal connection with Argentina but never indicted. (Admittedly, the Argentinian investigators point out that the gang included “at least” the arrested individuals, but their list is not exhaustive.)

Having put the suitcases under surveillance, the Argentinians waited out for almost a year, figuring out the scheme Blizniouk and Kovalchuk had planned to use to get the drugs out of the embassy. The scheme was simple: Ivan Blizniouk, who was also a professor at Instituto Superior de Seguridad Pública, a police academy in Buenos Aires, organized the participation of Argentinian police officers in knowledge exchange conferences in Russia. Under the pretext of such a trip, he intended to transport the suitcases with cocaine on the official delegation's plane (the investigation does not disclose whether Blizniouk managed to smuggle anything during his previous academic trips). He suggested sending five Argentinian cadets to Russia, but Kovalchuk thought they needed a lot more. He asked to organize the visit of 100 cadets – “four platoons” – for participation in the Victory Day parade in Saint Petersburg on May 9, 2017.

Not only did Blizniouk leverage his policeman status, but he also introduced himself as a “Russian embassy relations representative”. This was not an official post, but he had connections at the embassy and helped with translations and security matters. He also had contacts at the Russian foreign ministry, where he “delicately inquired” about Kovalchuk's reputation during his official trips to Russia, as specified by Investigative Prosecutor Taiano (pages 4, 8, and 39 of the indictment). Andrey Kovalchuk intended to have Blizniouk load “his personal suitcases” as diplomatic bags on a plane with these official delegations headed for Russia. According to the investigation, he did it “covertly from the Russian diplomats”.

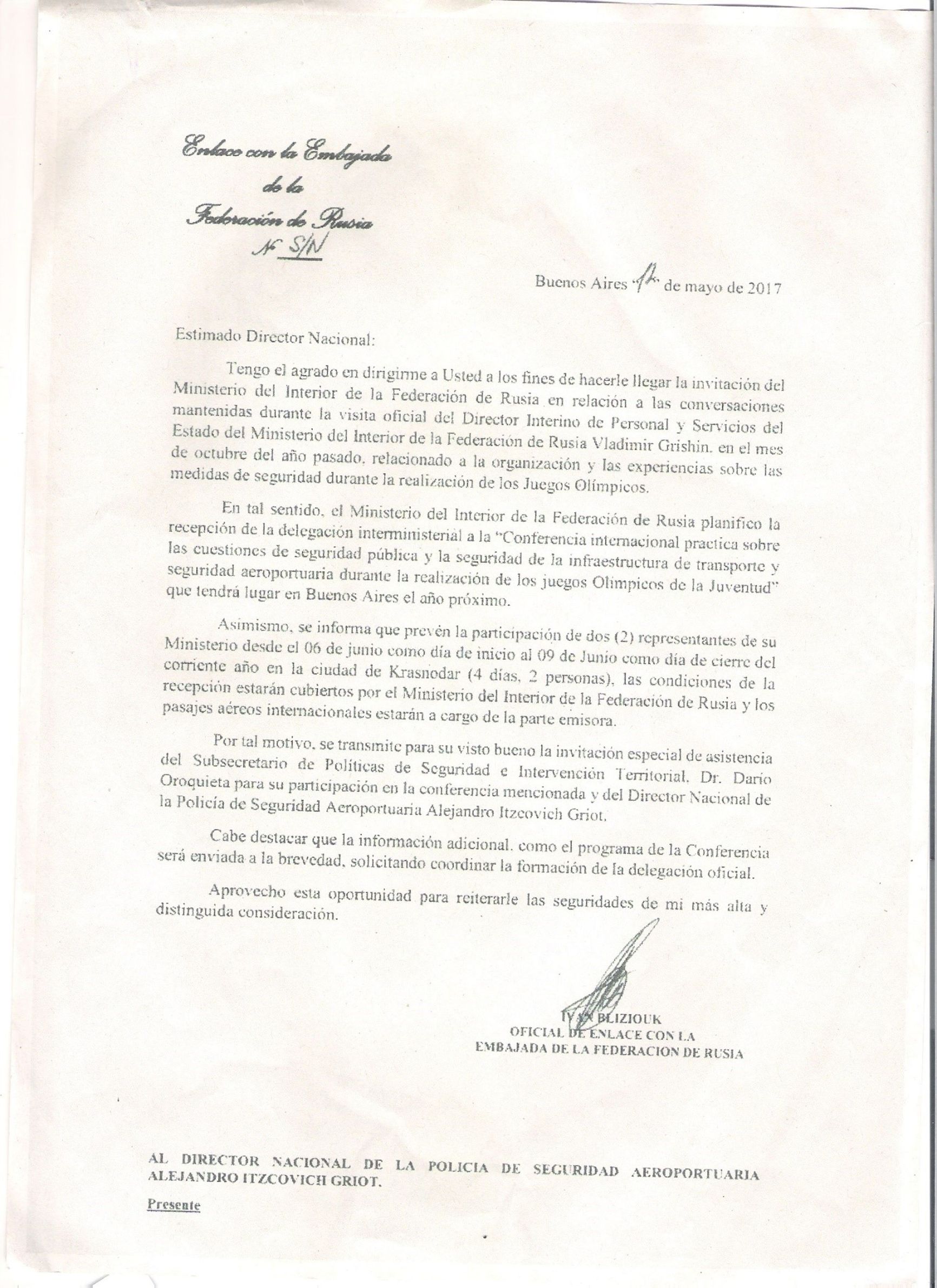

Apart from the diplomats, Blizniouk and Kovalchuk tried to get an in with the Airport Security Police (PSA, a special law enforcement agency in Argentina). On May 22, 2017, Blizniouk penned a letter to Alejandro Griot, head of the PSA, inviting him to Russia and signing the letter once again as a “Russian embassy relations representative”.

Griot accepted the invitation, visited the Krasnodar University of the MIA of Russia on June 13, and even received a medal and a diploma from the university's head. Ivan Blizniouk personally accompanied him on the trip and stayed in Russia until July 15 “to meet with Konstantin (Bossner) in Saint Petersburg”, according to page 29 of the indictment.

Blizniouk (far right) and Griot (second on the right) during their visit to Krasnodar

Blizniouk and Kovalchuk hoped to use first the cadets' trip and then Griot's visit to move the suitcases with cocaine to Moscow. However, they didn«t know that the Argentinian authorities were already tracking them and would not allow the controlled transfer of the drugs until they were ready, using different pretexts to stop the smugglers from hauling the cocaine on those two occasions. Under the agreement between the Argentinian investigators and the Russian embassy, the diplomats came up with excuses for not releasing the suitcases: for instance, the new logistics manager, Igor Rogov, “had gone on an urgent business trip” to Mar del Plata, taking the keys to the room with suitcases with him. Kovalchuk organizes a charter flight – “Bossner»s plane” – to get the bags out of the country, but embassy official Oleg Vorobyov tells them the ambassador is out, and no one else can authorize sending a minivan with diplomatic immunity to deliver the cargo to the airstairs because the deputy ambassador doesn«t have a diplomatic passport. “Tough luck!” says Kovalchuk, but there isn»t much he can do. In line with the investigators« instructions, embassy employees Oleg Vorobyov and Igor Rogov told Kovalchuk that he wouldn»t be able to transport his cargo until December 2017, when the official Russian delegation plane would be carrying the ambassador's possessions (page 72 of the indictment).

Eventually, according to a video by the Argentinian police, the suitcases with flour in packaging resembling that of diplomatic bags were transported by Flight RA-96023 of the Russian Special Detachment (the one Nikolai Patrushev typically uses). Meanwhile, Interfax«s sources at the Security Council of Russia denied the involvement of Patrushev»s plane in the operation. In general, using it for a regular drug bust would indeed have been a strange choice. By contrast, Patrushev«s personal involvement would make the appearance of his plane in Argentina logical. This particular plane often appears in different countries whenever the Kremlin needs to cover up a major scandal. Thus, Patrushev»s plane landed in Thailand when its authorities arrested Nastya Rybka (real name Anastasia Vashukevich). She was threatening to share the details of her lover Oleg Deripaska's negotiations on the intervention in the American election with the U. S. Patrushev also flew to Serbia to deal with the scandal around the arrested Russian intelligence officers who tried to stage a coup in Montenegro. Further on, after the launch of the investigation regarding Flight MH17, a Boeing Russia had accidentally taken down, Patrushev came to Malaysia to persuade the authorities to challenge the JIT's findings. The question is what actually happened in Argentina: a diplomatic scandal involving drug trafficking in the Russian diplomatic pouch or a special operation featuring Russian diplomats who courageously thwarted a major cocaine haul?

What actually happened in Argentina?

Immediately after the official version was released, with all of its gaps and inconsistencies, an alternative version emerged: it wasn't the embassy officials who found the stash but the Argentinian police, who uncovered the old scheme of drug trafficking via the diplomatic pouch. Moscow had to engage in a round of political negotiations to cover up the scandal, throwing a couple of pawns under the bus.

Argentina's official statements also contain hints confirming the alternative version. Bullrich remarked, for instance: “We believe that the drugs originated in Colombia, and one could assume that they may have entered [Argentina] through the same channel”. In March 2020, an Argentinian court of law refused to release Alexander Chikalo into home confinement, pointing out that “the gang planned to send the suitcases with cocaine to Russia through the diplomatic channels”.

And finally, a Russian embassy employee confessed to having packed contraband items into the diplomatic pouch for years. In his deposition in the case files, Ali Abyanov admits to sealing and “asking to seal” (an unknown individual or group) Kovalchuk«s suitcases as diplomatic bags back in 2012 and 2014. A cargo plane took the first such suitcase to Russia via Uruguay, and a direct military flight carried the other two. Abyanov asserts he thought the bags contained “wine, coffee, and cookies”, but this is what he said about Kovalchuk»s last 12 suitcases (two and then ten more), which he had hidden in the embassy school in 2015–2016. Abyanov«s words about the shipment via Uruguay are particularly significant. Thus, Chikalo and Blizniouk discuss in one of the intercepts that they used to smuggle drugs through Uruguay and wonder why the route has changed. (Even though they avoid using the word “cocaine” by replacing it with “buckwheat”, “cognac”, “pelts”, or “painting”, it»s not cookies they are talking about.)

The Argentinian investigators analyzed all of the intercepts and concluded: all of the participants were perfectly aware that they were smuggling cocaine through the diplomatic channels but came up with different versions for fear of wiretaps (“the Americans are onto us,” says Blizniouk to Chikalo on October 11, 2017). On the same day, Chikalo tells Blizniouk (after a few thwarted smuggling attempts, the accomplices are getting nervous) that he once found odor-masking discs in the suitcases Kovalchuk gave him. One does not need special substances to throw K-9 dogs off the track to transport pelts or cognac, let alone works of art. However, according to the indictment (page 55), the police detected such substances when examining the embassy's drug-filled suitcases on December 14, 2016.

The Russian foreign ministry started vehemently rebutting any hints at the involvement of the diplomatic pouch, but their inelegant manner only reinforced such suspicions. “No one could have shipped anything via the diplomatic pouch. It's impossible. <Such allegations> show nothing but ignorance of how the diplomatic pouch works,” stated Alexander Panov, diplomat and MGIMO professor, adding that even ordinary diplomats, let alone support staff, do not have direct access to the packing of diplomatic pouches. If the support staff is not allowed anywhere near diplomatic pouches, how did Blizniouk, Kovalchuk, and Abyanov expect their plan to work? Or could they have had more accomplices?

When speaking off the record, Argentinian security service officers do not mince words. Back at the end of 2018, a Colombian media called Semana published an investigation titled Diplomatic Drug Pouches. The article included interviews with anonymous Argentinian law enforcers unhappy with the investigation focusing on sidekicks. They insisted that the practice of drug trafficking via the Russian diplomatic pouch is pervasive throughout Latin America. Thus, an Argentinian Gendarmerie investigator asserted:

Mid-level diplomatic officials like Abyanov and other detainees could not have completed an operation of such scale.” As to the volume, 400 kilos, it is apparent that the operation wasn«t their first because drug traffickers don»t risk sending a first batch this big unless they are confident it«ll reach its destination. Furthermore, the indictment doesn»t charge any of the other officials who were evidently involved, and this is because they weren«t ordinary diplomats from the embassy. At least one of them works for the SVR (Russia»s foreign intelligence service).

As many as three sources confirmed the defendants' connection to the SVR to the magazine. Referring to the investigation materials, Semana also wrote that Abyanov used his diplomatic status to smuggle drugs from Uruguay at least three times.

The case files, therefore, confirm the Argentinian police officers' statements. Thus, on October 11, 2017, rogue policeman Blizniouk calls his accomplice Chikalo to discuss the diplomatic pouch drug haul plan. They accidentally mention that, before Kovalchuk “fell out with the ambassador”, he had regularly smuggled drugs via the diplomatic pouch:

“What«s your take on our common friend»s offer?”

“You know, if you have a trusting relationship with these people, transporting it as a diplomatic pouch is a piece of cake. The embassy has to participate in some way.”

“Of course. We need at least a vehicle with diplomatic immunity.”

“First, a vehicle with diplomatic immunity, second, the papers confirming the diplomatic pouch status or something of the sort. Otherwise, when you say you want to pass without a security check, they«ll say, »Oh, you do, do you? Open up all of them.'”

<...>

“Now that the diplomatic pouch isn«t an option because he»s fallen out with the ambassador, he doesn«t know what to do. This could be what»s happening. Can you imagine the volumes of drug trafficking in the past?”

“Sure, I can.”

<...>

“But if he shipped them earlier, what's the problem?”

“He«s at odds with the ambassador. The ambassador provided a vehicle, a minivan with papers confirming the cargo was a diplomatic pouch. He»s at a loss now. He says he«ll go to Ivan. They»ve definitely done it this way before.”

In all appearances, the “falling out” coincided with the joint operation start, when Ambassador Koronelli turned in Blizniouk and Chikalo. Another sign of the Russian diplomats' complicity was a brute-force attack on Argentinian police servers. A quote from the report of the Argentinian secret services titled Tetris Botnet dated May 29, 2018 (made available to The Insider):

On May 21, 2018, the Technology Management Directorate of the Airport Security Police (PSA) detected a rage of activities targeting the Security Ministry and its services. The most notable event was a massive scanning of ports on servers with IP addresses matching the official servers of the PSA, the Argentine Naval Prefecture, the Argentine National Gendarmerie, and the Security Ministry performed from an IP address that belongs to Russia. It was followed by brute-force attacks on the PSA mail server via the SMTP protocol from 14 IP addresses (with a history of hacker attacks) located in different countries.

The Argentinian intelligence officers assumed that the attackers aimed to extract information from a specific server and targeted multiple servers to create a smoke screen. Hacker attacks targeting information on the progress of investigation concerning Russia are a part of the landscape. Thus, GRU hackers attempted to access the Spiez Laboratory, the Swiss institute for the protection against nuclear, biological, and chemical threats, which analyzed the Novichok samples after the Salisbury poisonings. They also attacked the JIT's servers to obtain investigation materials on Boeing MH17 (and somewhat succeeded, extracting a few minor documents).

Interestingly, the attack (perpetuated on May 21, 2018) coincided with the completion of the indictment, which would be of interest to the Russian intelligence but inaccessible through the official channels (the document was only for the judge's eyes at this point). The Russian authorities would hardly have been so desperate to lay their hands on the indictment, had their role been limited to helping the investigation.

Curiously, Ambassador Koronelli, who heroically helped catch the smugglers in the official narrative, was quietly transferred to Mexico even before the investigation concluded. According to our source close to the Argentinian investigators, his transfer is a direct consequence of his involvement in the cocaine scheme. No less remarkably, on December 20, 2016, just six days after Koronelli reached out to the Argentinian ministry of interior, supposedly at his own initiative, Moscow witnessed the assassination of Pyotr Polshikov, ambassador extraordinary and plenipotentiary and senior counselor of the Latin American Department of the Russian foreign ministry, previously head of said department. The Russian foreign ministry immediately denied any connection with the cocaine scandal, calling his assassination “a tragic accident unrelated to the official activities of the deceased”. However, journalists soon found out that Polshikov had not just “tragically died”. He had been shot in the head, with the gun missing, so it became apparent that sweeping his death under the rug as an “accident” wasn't an option. The police are yet to solve his murder, and the only viable hypothesis is his involvement in drug trafficking.

The Baron and the Kremlin

Kovalchuk«s superior, Konstantin Loskutnikov, introduces himself as “Baron von Bossner” in all seriousness and looks somewhat comical, at first sight, with his all-season three-piece suite, thick beard, and the inevitable cigar in his mouth. The internet is chock-full of his interviews – blatant fluff pieces – in which he speaks about his outstanding achievements (he publishes some of these interviews in his own lifestyle magazine and distributes it for free). He asserts that his primary source of income is a cigar business, which does exist (he rents factories in Nicaragua and the Dominican Republic), but its profitability is open to speculation. According to The Insider»s source, who worked at Bossner«s Berlin office, the business is “rickety” and cannot serve as the primary resource for his “charity work”. The Insider studied the German Commercial Register and found out that Golden Mile GmbH (Bossner»s trademark) hadn't turned a profit until 2018 (197,000 euros). Until then, the business had been declaring losses of up to 800,000 euros a year.

Bossner«s office looks exactly like that of a typical straw company. Sociologist Igor Eidman, who lives in Berlin, shared that he»d visited the place a couple of months before the Argentinian debacle. “I needed a film editor for a documentary about Russian propaganda. A friend of a friend supplied an address. I came there and saw three plaques on the wall: «Bossner Cognac & Cigars», «Russian Orthodox Philanthropists», and «Slot Machines». All three companies shared an office of about six rooms. The editor was going to cut the film right at the office (Bossner also runs a YouTube channel with 20 to 200 views per video). I told him: «Look, why don»t you ask your boss first? Russian Orthodox philanthropists sound like they have a lot to do with the Kremlin.' He called me back and told his boss prohibited him from cutting opposition videos.”

Bossner tried to deny that Kovalchuk works for him, but the intercepts suggest otherwise. Thus, Chikalo and Blizniouk (who head the Russian Orthodox Philanthropists in Latin America) mention that Kovalchuk sent a jet “with cognac from Bossner” to offer as gifts to the police (this was their third failed attempt to smuggle the suitcases with cocaine by loading them on the returning plane). “[Kovalchuk] gives me $2,000 and asks me to arrange a meeting with my bosses at a restaurant. We introduce him as the Baron«s representative <...> and then we ask another question – about something we need to put on a plane without security checks. We need to be open with them, and they»ll say if they can make it happen.”

“Russian Orthodox philanthropist” von Bossner (Loskutnikov)

On November 14, 2017, Kovalchuk and Blizniouk arranged a meeting with the management of the Higher Institute of Public Security of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, where Kovalchuk greeted the high-ranking police officers on behalf of “the Bossner foundation”. Ever an opportunist, Kovalchuk would introduce himself in a million ways (as a securocrat, diplomat, businessman, etc.). Still, working with Bossner, Chikalo and Blizniouk would have known whether Kovalchuk was indeed his representative, and after all, he had procured the plane with cognac.

Another curious conversation deals with arranging Kovalchuk«s meeting with Saint Petersburg»s governor Georgy Poltavchenko to obtain written confirmation of the city«s willingness to receive Argentinian police cadets to sign an agreement with Saint Petersburg University of the MIA of Russia. According to the investigators, they needed an agreement for further smuggling of cocaine under the “police delegation exchange” cover. Blizniouk asks Kovalchuk to ensure Bossner»s participation in the meeting. “I'd like Konstantin to be at that meeting so that we can push the deal through. Make it a personal meeting with Konstantin – with both of you.” To remind you, Blizniouk prolonged his stay in Russia to meet with Bossner in Saint Petersburg.

Many of the intercepts explicitly confirm that Bossner-Loskutnikov was the mastermind behind the smuggling scheme. Here is an example of a conversation proving that it was Konstantin Bossner who launched the cocaine traffic. The Insider quotes a back-translation from Spanish as per the text of the indictment.

Kovalchuk: “Hi, how is it going for you? I«ve had my Skype fixed. They haven»t brought it to my place, though.”

Blizniouk: “Great.”

Kovalchuk: “I«ll pick it up tomorrow, I think, not today. Hey, I have a question for you. I»m coming next week.”

Blizniouk: “And?”

Kovalchuk: “Konstantin here is asking me if you«ve kept in touch with that guy... what»s his name... with the Armenian surname, and the other one... Remember, the ones that were on the yacht that day in Saint Pete's?”

Blizniouk: “And?”

Kovalchuk: “What do you mean, «and»? Are you or are you not in touch?”

Blizniouk: “Sure, I am. Depends on what he wants. We don«t drink beer together. It»s a business relationship.”

Kovalchuk: “Ha-ha. The thing is, a jet will arrive. Konstantin«s acquaintances are coming on board his private jet. It»s my understanding that I'll be around your parts too. He wants to send them a box of cognac and cigars each.”

Blizniouk: “Send whom?”

Kovalchuk: “Those friends of his. The Armenian – I only remember that he has an Armenian surname – another guy, and the third one, head of the airport security if I'm not mistaken.”

Blizniouk: “All right. Where do I come in?”

Kovalchuk: “He«ll send them the cognac so that they pick it up themselves, or we»ll drive them to pick it up together. From that private jet.”

Blizniouk: “I got that, but who is supposed to do the picking up?”

Kovalchuk: “I'll tell you. A private jet will arrive.”

Blizniouk: “No problem. Send me all the details for me to arrange everything in advance. Don't make me talk to these people on the day before the plane arrives.”

Kovalchuk: “Got it. There«s a 90-percent chance that I»ll be there. So we'll go together anyway. But he wants to email them. I asked him: why? Ivan can take care of it. Email Ivan instead. And besides, is it possible to arrange it in such a way that I could send the wine with the return flight?”

Blizniouk: “On the same plane?”

Kovalchuk: “Yes.”

Blizniouk: “Listen, mate, we«ve got to talk to them first. If they can have someone pick up what we»re sending them. See? <>. And then tell Konstantin to email me with a note: «Ivan, this is for the following addressees», and I'll show it to the people in question.” <>

The “Armenian” they mention is Argentinian policeman Carlos Kevorkian. He joined Griot, Kovalchuk, and Bossner on the so-called knowledge exchange visit to the Russian ministry of interior, where the Russians treated them to a yacht ride and other entertaining activities. These two police officers were to oversee the detection of cocaine in the suitcases. Kovalchuk tries to resume their relationship in the fall of 2017, presumably, because they had not required the policemen's assistance earlier, sending contraband with support from the ambassador via the diplomatic pouch without security checks, but their “falling out” had changed everything.

In all, the connection between Kovalchuk and Bossner-Loskutnikov is apparent. Yet, whereas the former was extradited and arrested, no one has shown any interest in the latter. A German resident, he makes political statements about uniting the FRG with Russia, organizes book presentations for pro-Kremlin author Alexander Rahr, plagues the mayor of Vilnius on behalf of the German scientists and entrepreneurs« club about restoring Soviet memorials, and engages in other provocative activities in line with the Kremlin»s current policy.

Konstantin Loskutnikov (Bossner), Alexander Rahr, and Sahra Wagenknecht (Die Linke)

Apart from pro-Kremlin political analysts, Bossner promotes pro-Kremlin movies. Thus, he supported a Russian-language film festival in Marbella (where he owns a villa and a straw company called Marmoles Velerin and yielding a stunning profit of 6,000 euros a year). According to Maria Eliseeva, former jury member at Marbella International Russian Film Festival, Bossner usurped control of the festival a few years ago. “He was actively trying to establish contact with the festival. Too greedy to throw in his own money, he promised he would secure funding from the Russian ministry of culture. He drives around Marbella in two cars with security guards. Appearing on our radar a couple of years earlier, in 2016, he was trying to dissuade the jury from awarding the first prize to Vitaly Mansky. He said that «the girls» – the festival organizers – wouldn«t get support from the ministry and that Medinsky (the Russian minister of culture) was furious with Mansky. He also asserted that there wasn»t enough money to finance the festival and that his charity projects in Berlin would suffer if Mansky were to receive the prize. His charity allegedly helps children in Berlin with assistance from the Russian embassy. «Don»t you want to help children in Berlin?« he would often say. After a three-hour altercation, he called the Russian foreign ministry in the jury»s presence. His conversation partner strongly advised us against giving the prize to Mansky. Failing to persuade the jury, he went on to brainwash the organizers – the «girls», as he called them – and succeeded. The festival became pro-Putinist.”

Bossner likes to brag about his connections and regular participation in the Saint Petersburg International Economic Forum, but forging relationships by throwing money around is no big deal. Neither is paying journalists for fluff pieces. None of the above, however, would have allowed him to shrug off drug charges. He has most likely evaded arrest simply because the Russian authorities were trying to cover up the case as soon as humanly possible.

The Argentinians, too, confined themselves to just a handful of main defendants. In the indictment dated May 21, 2018, Investigative Prosecutor Eduardo Taiano clarifies: Ali Abyanov and Kovalchuk were in charge of logistics – moving the suitcases – whereas Blizniouk leveraged his connections, many of which he«d established through bribery, to prevent the detection of drugs, for instance, by K-9 units. Bossner is not a defendant. The indictment mentions a document signed by the Federal Administration of Public Revenue of Argentina to certify that “the Bossner Company is not registered in Argentina”. (Said company attracted the investigators» attention because embassy employee Oleg Vorobyov insisted in his deposition: “I am certain that Kovalchuk receives income through the Bossner Company and engages it to organize formal visits, which, as we suspect, were used as a cover for the smuggling of drugs.”)

Why would the Argentinian law enforcement draw up such a short list of defendants and never request Bossner«s extradition? Apart from a political agreement with Moscow, a possible explanation is the extreme complexity of investigating Russian diplomats without the country»s cooperation. “The investigations involving the diplomatic pouch are highly complicated,” a European customs police offices explained to The Insider. “In theory, if we suspect that a diplomatic bag contains prohibited items, we must engage the employees of the relevant embassy, who would then task the investigative authorities of their state with conducting the investigation. I once tried to insist on unsealing a Nigerian diplomatic bag, but the process came to a halt at the note-of-protest stage.”